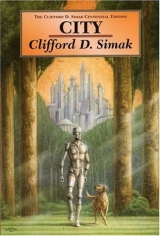

Текст книги "City"

Автор книги: Clifford D. Simak

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Clifford D. Simak

City

EDITOR'S PREFACE

These are the stories that the Dogs tell when the fires burn high and the wind is from the north. Then each family circle gathers at the hearthstone and the pups sit silently and listen and when the story's done they ask many questions:

"What is Man?" they'll ask.

Or perhaps: "What is a city?"

Or "What is a war?"

There is no positive answer to any of these questions. There are suppositions and there are theories and there are many educated guesses, but there are no answers.

In the family circle, many a storyteller has been forced to fall back on the ancient explanation that it is nothing but a story, there is no such thing as a Man or city, that one does not search for truth in a simple tale, but takes it for its pleasure and lets it go at that.

Explanations such as these, while they may do to answer pups, are no explanations. One does search for truth in such simple tales as these.

The legend, consisting of eight tales, has been told for countless centuries. So far as can be determined, it has no historic starting point; the most minute study of it fails entirely to illustrate the stages of its development. There is no doubt that through many years of telling it has become stylized, but there is no way to trace the direction of its stylization.

That it is ancient and, as some writers claim, that it may be of non-Doggish origin in part, is borne out by the abundance of jabberwocky which studs the tales-words and phrases, (and worst of all, ideas) which have no meaning now and may have never had a meaning. Through telling and retelling, these words and phrases have become accepted, have been assigned, through context, a certain arbitrary value. But there is no way of knowing whether or not these arbitrary values even approximate the original meaning of the words.

This edition of the tales will not attempt to enter into the many technical arguments concerning the existence or nonexistence of Man, of the puzzle of the city, of the several theories relating to war, or of the many other questions which arise to plague the student who would seek in the legend some evidence of its having roots in some basic or historic truth.

The purpose of this edition is only to give the full, unexpurgated text of the tales as they finally stand. Chapter notes are utilized to point out the major points of speculation, but with no attempt at all to achieve conclusions. For those who wish some further understanding of the tales or of the many points of consideration which have arisen over them there are ample texts, written by Dogs of far greater competence than the present editor.

Recent discovery of fragments of what originally must have been an extensive body of literature has been advanced as the latest argument which would attribute at least part of the legend to mythological (and controversial) Man rather than to the Dogs. But until it can be proved that Man did, in fact, exist, argument that the discovered fragments originated with Man can have but little point.

Particularly significant or disturbing, depending upon the viewpoint that one takes, is the fact that the apparent title of the literary fragment is the same as the title of one of the tales in the legend here presented. The word itself, of course, is entirely meaningless.

The first question, of course, is whether there ever was such a creature as Man. At the moment, in the absence of positive evidence, the sober consensus must be that there was not, that Man, as presented in the legend, is a figment of folklore invention. Man may have risen in the early days of Doggish culture as an imaginary being, a sort of racial god, on which the Dogs might call for help, to which they might retire for comfort.

Despite these sober conclusions, however, there are those who see in Man an actual elder god, a visitor from some mystic land or dimensions, who came and stayed awhile and helped and then passed on to the place from which he came.

There still are others who believe that Man and Dog may have risen together as two co-operating animals, may have been complementary in the development of a culture, but that at some distant point in time they reached the parting of the ways.

Of all the disturbing factors in the tales (and they are many) the most disturbing is the suggestion of reverence which is accorded Man. It is hard for the average reader to accept this reverence as mere story-telling. It goes far beyond the perfunctory worship of a tribal god; one almost instinctively feels that it must be deep-rooted in some now forgotten belief or rite involving the pre-history of our race.

There is little hope now, of course, that any of the many areas of controversy which revolve about the legend ever will be settled.

Here, then, are the tales, to be read as you see fit-for pleasure only, for some sign of historical significance, for some hint of hidden meaning. Our best advice to the average reader: Don't take them too much to heart, for complete confusion, if not madness, lurks along the road.

NOTES ON THE FIRST TALE

There is no doubt that, of all the tales, the first is the most difficult for the casual reader. Not only is its nomenclature trying, but its logic and its ideas seem, at first reading, to be entirely alien. This may be because in this story and the next a Dog plays no part, is not even mentioned. From the opening paragraph in this first tale the reader is pitchforked into an utterly strange situation, with equally strange characters to act out its solution. This much may be said for the tale, however – by the time one has laboured his way through it the rest of the tales, by comparison, seem almost homey.

Overriding the entire tale is the concept of the city. While there is no complete understanding of what a city might be, or why it should be, it is generally agreed that it must have been a small area accommodating and supporting a large number of residents. Some of the reasons for its existence are superficially explained in text, but Bounce, who has devoted a lifetime to the study of the tales, is convinced that the explanation is no more than the clever improvisations of an ancient storyteller to support an impossible concept. Most students of the tales agree with Bounce that the reasons as given in the tale do not square with logic and some, Rover among them, have suspected that here we may have an ancient satire, of which the significance has been lost.

Most authorities in economics and sociology regard such an organization as a city an impossible structure, not only from the economic standpoint, but from the sociological and psychological as well. No creature of the highly nervous structure necessary to develop a culture, they point out, would be able to survive within such restricted limits. The result, if it were tried, these authorities say, would lead to mass neuroticism which in a short period of time would destroy the very culture which had built the city.

Rover believes that in the first tale we are dealing with almost pure myth and that as a result no situation or statement can be accepted at face value, that the entire tale must be filled with a symbolism to which the key has long been lost. Puzzling, however, is the fact that if it is a myth-concept, and nothing more, that the form by now should not have rounded itself into the symbolic concepts which are the hallmark of the myth. In the tale there is for the average reader little that can be tagged as myth-content. The tale itself is perhaps the most angular of the lot-raw-boned and slung together, with none of the touches of finer sentiment and lofty ideals which are found in the rest of the legend.

The language of the tale is particularly baffling. Phrases such as the classic "dadburn the kid" have puzzled semanticists for many centuries and there is today no closer approach to what many of the words and phrases mean than there was when students first came to pay some serious attention to the legend.

The terminology for Man has been fairly well worked out, however. The plural for this mythical race is men, the racial designation is human, the females are women or wives (two terms which may at one time have had a finer shade of meaning, but which now must be regarded as synonymous), the pups are children. A male pup is a boy. A female pup a girl.

Aside from the concept of the city, another concept which the reader will find entirely at odds with his way of life and which may violate his very thinking, is the idea of war and of killing. Killing is a process, usually involving violence, by which one living thing ends the life of another living thing. War, it would appear, was mass killing carried out on a scale which is inconceivable.

Rover, in his study of the legend, is convinced that the tales are much more primitive than is generally supposed, since it is his contention that such concepts as war and killing could never come out of our present culture, that they must stem from some era of savagery of which there exists no record.

Tige, who is almost alone in his belief that the tales are based on actual history and that the race of Man did exist in the primordial days of the Dogs' beginning, contends that this first tale is the story of the actual breakdown of Man's culture. He believes that the tale as we know it today may be a mere shadow of some greater tale, a gigantic epic which at one time may have measured fully as large or larger than today's entire body of the legend. It does not seem possible, he writes, that so great an event as the collapse of a mighty mechanical civilization could have been condensed by the tale's contemporaries into so small a compass as the present tale. What we have here, says Tige, is only one of many tales which told the entire story and that the one which does remain to us may be no more than a minor one.

I. CITY

Gramp Stevens sat in a lawn chair, watching the mower at work, feeling the warm, soft sunshine seep into his bones. The mower reached the edge of the lawn, clucked to itself like a contented hen, made a neat turn and trundled down another swath. The bag holding the clippings bulged.

Suddenly the mower stopped and clicked excitedly. A panel in its side snapped open and a cranelike arm reached out, Grasping steel fingers fished around in the grass, came up triumphantly with a stone clutched tightly, dropped the stone into a small container, disappeared back into the panel again. The lawn mower gurgled, purred on again, following its swath.

Gramp grumbled at it with suspicion.

"Some day," he told himself, "that dadburned thing is going to miss a lick and have a nervous breakdown."

He lay back in the chair and stared up at the sun-washed sky. A helicopter skimmed far overhead. From somewhere inside the house a radio came to life and a torturing crash of music poured out. Gramp, hearing it, shivered and bunkered lower in the chair.

Young Charlie was settling down for a twitch session. Dadburn the kid.

The lawn mower chuckled past and Gramp squinted at it maliciously.

"Automatic," he told the sky. "Ever' blasted thing is automatic now. Getting so you just take a machine off in a corner and whisper in its ear and it scurries off to do the job."

His daughter's voice came to him out of the window, pitched to carry above the music.

"Father!"

Gramp stirred uneasily. "Yes, Betty."

"Now, Father, you see you move when that lawn mower gets to you. Don't try to out-stubborn it. After all, it's only a machine. Last time you just sat there and made it cut around you. I never saw the beat of you."

He didn't answer, letting his head nod a bit, hoping she would think he was asleep and let him be.

"Father," she shrilled, "did you hear me?"

He saw it was no good. "Sure, I heard you," he told her. "I was just flexing to move."

He rose slowly to his feet, leaning heavily on his cane.

Might make her feel sorry for the way she treated him when she saw how old and feeble he was getting. He'd have to be careful, though. If she knew he didn't need the cane at all, she'd be finding jobs for him to do and, on the other hand, if he laid it on too thick, she'd be having that fool doctor in to pester him again.

Grumbling, be moved the chair out into that portion of the lawn that had been cut. The mower, rolling past, chortled at him fiendishly.

"Some day," Gramp told it, "I'm going to take a swipe at you and bust a gear or two."

The mower hooted at him and went serenely down the lawn. From somewhere down the grassy street came a jangling of metal, a stuttered coughing.

Gramp, ready to sit down, straightened up and listened.

The sound came more clearly, the rumbling backfire of a balky engine, the clatter of loose metallic parts.

"An automobile!" yelped Gramp. "An automobile, by cracky!"

He started to gallop for the gate, suddenly remembered tha the was feeble and subsided into a rapid hobble.

"Must be that crazy Ole Johnson," he told himself. "He's the only one left that's got a car. Just too dadburned stubborn to give it up."

It was Ole.

Gramp reached the gate in time to see the rusty, dilapidated old machine come bumping around the corner, rocking and chugging along the unused street. Steam hissed from the over-heated radiator and a cloud of blue smoke issued from the exhaust, which had lost its muffler five years or more ago.

Ole sat stolidly behind the wheel, squinting his eyes, trying to duck the roughest places, although that was hard to do, for weeds and grass had overrun the streets and it was hard to see what might be underneath them.

Gramp waved his cane.

"Hi, Ole," he shouted.

Ole pulled up, setting the emergency brake. The car gasped, shuddered, coughed, died with a horrible sigh.

"What you burning?" asked Gramp.

"Little bit of everything," said Ole. "Kerosene, some old tractor oil I found out in a barrel, some rubbing alcohol."

Gramp regarded the fugitive machine with forthright admiration. "Them was the days," he said. "Had one myself used to be able to do a hundred miles an hour."

"Still O.K.," said Ole, "if you only could find the stuff to run them or get the parts to fix them. Up to three, four years ago I used to be able to get enough gasoline, but ain't seen none for a long time now. Quit making it, I guess. No use having gasoline, they tell me, when you have atomic power."

"Sure," said Champ. "Guess maybe that's right, but you can't smell atomic power. Sweetest thing I know, the smell of burning gasoline. These here helicopters and other gadgets they got took all the romance out of travelling, somehow."

He squinted at the barrels and baskets piled in the back seat.

"Got some vegetables?" he asked.

"Yup," said Ole. "Some sweet corn and early potatoes and a few baskets of tomatoes. Thought maybe I could sell them."

Champ shook his head. "You won't, Ole. They won't buy them. Folks has got the notion that this new hydroponics stuff is the only garden sass that's fit to eat. Sanitary, they say, and better flavoured."

"Wouldn't give a hoot in a tin cup for all they grow in them tanks they got," Ole declared, belligerently. "Don't taste right to me, somehow. Like I tell Martha, food's got to be raised in the soil to have any character."

He reached down to turn over the ignition switch.

"Don't know as it's worth trying to get the stuff to town," he said, "the way they keep the roads. Or the way they don't keep them, rather. Twenty years ago the state highway out there was a strip of good concrete and they kept it patched and ploughed it every winter. Did anything, spent any amount of money to keep it open. And now they just forgot about it. The concrete's all broken up and some of it has washed out. Brambles are growing in it. Had to get out and cut away a tree that fell across it one place this morning."

"Ain't it the truth," agreed Champ.

The car exploded into life, coughing and choking. A cloud of dense blue smoke rolled out from under it. With a jerk it stirred to life and lumbered down the street.

***

Gramp clumped back to his chair and found it dripping wet. The automatic mower, having finished its cutting job, had rolled out the hose, was sprinkling the lawn.

Muttering venom, Gramp stalked around the corner of the house and sat down on the bench beside the back porch. He didn't like to sit there, but it was the only place he was safe from the hunk of machinery out in front.

For one thing, the view from the bench was slightly depressing, fronting as it did on street after street of vacant, deserted houses and weed-grown, unkempt yards.

It had one advantage, however. From the bench he could pretend be was slightly deaf and not hear the twitch music the radio was blaring out.

A voice called from the front yard.

"Bill! Bill, where be you?"

Gramp twisted around.

"Here I am, Mark. Back of the house. Hiding from that dadburned mower."

Mark Bailey limped around the corner of the house, cigarette threatening to set fire to his bushy whiskers.

"Bit early for the game, ain't you?" asked Grump.

"Can't play no game today," said Mark.

He hobbled over and sat down beside Grump on the bench.

"We're leaving," he said.

Cramp whirled on him. "You're leaving!"

"Yeah. Moving out into the country. Lucinda finally talked Herb into it. Never gave him a minute's peace, I guess. Said everyone was moving away to one of them nice country estates and she didn't see no reason why we couldn't."

Cramp gulped. "Where to?"

"Don't rightly know," said Mark. "Ain't been there myself. To north some place. Up on one of the lakes. Got ten acres of land. Lucinda wanted a hundred, but Herb put down his foot and said ten was enough. After all, one city lot was enough for all these years."

"Betty was pestering Johnny, too," said Gramp, "but he's holding out against her. Says he simply can't do it. Says it wouldn't look right, him the secretary of the Chamber of Commerce and all, if he went moving away from the city."

"Folks are crazy," Mark declared. "Plumb crazy."

"That's a fact," Cramp agreed. "Country crazy, that's what they are. Look across there."

He waved his hand at the streets of vacant houses. "Can remember the time when those places were as pretty a bunch of homes as you ever laid your eyes on. Good neighbours, they were. Women ran across from one back door to another to trade recipes. And the men folks would go out to cut the grass and pretty soon the mowers would all be sitting idle and the men would be ganged up, chewing the fat. Friendly people, Mark. But look at it now."

Mark stirred uneasily. "Got to be getting back, Bill. Just sneaked over to let you know we were lighting out. Lucinda's got me packing. She'd be sore if she knew I'd run out."

Cramp rose stiffly and held out his hand. "I'll be seeing you again? You be over for one last game?"

Mark shook his head "Afraid not, Bill".

They shook hands awkwardly, abashed. "S5ure will miss them games," said Mark.

"Me, too," said Gramp. "I won't have nobody once you're gone."

"So long, Bill," said Mark.

"So long," said Champ.

He stood and watched his friend hobble around the house, felt the cold claw of loneliness reach out and touch him with icy fingers. A terrible loneliness. The loneliness of age – of age and the outdated. Fiercely, Gramp admitted it. He was outdated. He belonged to another age. He had outstripped his time, lived beyond his years.

Eyes misty, he fumbled for the cane that lay against the bench, slowly made his way towards the sagging gate that opened on to the deserted street back of the house.

***

The years had moved too fast. Years that had brought the family plane and helicopter, leaving the auto to rust in some forgotten place, the unused roads to fall into disrepair. Years that had virtually wiped out the tilling of the soil with the rise of hydroponics. Years that had brought cheap land with the disappearance of the farm as an economic unit, had sent city people scurrying out into the country where each man, for less than the price of a city lot, might own broad acres. Years had revolutionized the construction of homes to a point where families simply walked away from their old homes to the new ones that could be bought, custom-made, for less than half the price of a prewar structure and could be changed at small cost, to accommodate need of additional space or just a passing whim.

Gramp sniffed. Houses that could be changed each year, like one would shift around the furniture. What kind of thing was that?

He plodded slowly down the dusty path that was all that remained of what a few years before had been a busy residencial street. A street of ghosts, Cramp told himself – of furtive, little ghosts that whispered in the night. Ghosts of playing children, ghosts of upset tricycles and canted coaster wagons. Ghosts of gossiping housewives. Ghosts of shouted greetings. Ghosts of flaming fireplaces and chimneys smoking of a winter night.

Little puffs of dust rose around his feet and whitened the cuffs of his trousers.

There was the old Adams place across the way. Adams had been mighty proud of it, he remembered. Grey field stone front and picture windows. Now the stone was green with creeping moss and the broken windows gaped with ghastly leer. Weeds choked the lawn and blotted out the stoop. An elm tree was pushing its branches against the gable. Gramp could remember the day Adams had planted that elm tree.

For a moment he stood there in the grass-grown street, feet in the dust, both hands clutching the curve of his cane, eyes closed.

Through the fog of years he heard the cry of playing children, the barking of Conrad's yapping pooch from down the street. And there was Adams, stripped to the waist, plying the shovel, scooping out the hole, with the elm tree, roots wrapped in burlap, lying on the lawn.

May, 1946. Forty-four years ago. Just after he and Adams had come home from the war together.

Footsteps padded in the dust and Gramp, startled, opened his eyes.

Before him stood a young man. A man of thirty, perhaps. Maybe a bit less.

"Good morning," said Gramp.

"I hope," said the young man, "that I didn't startle you."

"You saw me standing here," asked Gramp, "like a danged fool, with my eyes shut?"

The young man nodded.

"I was remembering," said Gramp.

"You live around here?"

"Just down the street. The last one in this part of the City."

"Perhaps you can help me then."

"Try me," said. Gramp.

The young man stammered. "Well, you see, it's like this. I'm on a sort of... well, you might call it a sentimental pilgrimage-"

"I understand," said Gramp. "So am I."

"My name is Adams," said the young man. "My grandfather used to live around here somewhere. I wonder-"

"Right over there," said Gramp.

Together they stood and stared at the house.

"It was a nice place once," Gramp told him. "Your grand-daddy planted that tree right after he came home from the war. I was with him all through the war and we came home together. That was a day for you..."

"It's a pity," said young Adams. "A pity..."

But Gramp didn't seem to hear him. "Your granddaddy?" he asked. "I seem to have lost track of him."

"He's dead," said young Adams. "Quite a number of years ago."

"He was messed up with atomic power," said Gramp.

"That's right," said Adams proudly. "Got into it just as soon as it was released to industry. Right after the Moscow agreement."

"Right after they decided," said Gramp, "they couldn't fight a war."

"That's right," said Adams.

"It's pretty hard to fight a war," said Gramnp, "when there's nothing you can aim at."

"You mean the cities," said Adams.

"Sure," said Granip, "and there's a funny thing about it. Wave all the atom bombs you wanted to and you couldn't scare them out. But give them cheap land and family planes and they scattered just like so many dadburned rabbits."

***

John I. Webster was striding up the broad stone steps of the city hall when the walking scarecrow carrying a rifle under his arm caught up with him and stopped him.

"Howdy, Mr. Webster," said the scarecrow.

Webster stared, then recognition crinkled his face.

"It's Levi," he said. "How are things going, Levi?"

Levi Lewis grinned with snagged teeth. "Fair to middling. Gardens are coming along and the young rabbits are getting to be good eating."

"You aren't getting mixed up in any of the hell raising that's being laid to the houses?" asked Webster.

"No, sir," declared Levi. "Ain't none of us Squatters mixed up in any wrong-doing. We're law-abiding God-fearing people, we are. Only reason we're there is we can't make a living no place else. And us living in them places other people up and left ain't harming no one. Police are just blaming us for the thievery and other things that's going on, knowing we can't protect ourselves. They're making us the goats."

"I'm glad to hear that," said Webster. "The chief wants to burn the houses."

"If he tries that," said Levi, "he'll run against something he ain't counting on. They run us off our farms with this tank farming of theirs but they ain't going to run us any farther."

He spat across the steps.

"Wouldn't happen you might have some jingling money on you?" he asked. "I'm fresh out of cartridges and with them rabbits coming up-"

Webster thrust his fingers into a vest pocket, pulled out a half dollar.

Levi grinned. "That's obliging of you, Mr. Webster. I'll bring a mess of squirrels, come fall."

The Squatter touched his hat with two fingers and retreated down the steps, sun glinting on the rifle barrel. Webster turned up the steps again.

The city council session already was in full swing when he walked into the chamber.

Police Chief Jim Maxwell was standing by the table and Mayor Paul Carter was talking.

"Don't you think you may be acting a bit hastily, Jim, in urging such a course of action with the houses?"

"No, I don't," declared the chief. "Except for a couple of dozen or so, none of those houses are occupied by their rightful owners, or rather, their original owners. Every one of them belongs to the city now through tax forfeiture. And they are nothing but an eyesore and a menace. They have no value. Not even salvage value. Wood? We don't use wood any more. Plastics are better. Stone? We use steel instead of stone. Not a single one of those houses have any material of marketable value.

"And in the meantime they are becoming the haunts of petty criminals and undesirable elements. Grown up with vegetation as the residential sections are, they make a perfect hideout for all types of criminals. A man commits a crime and heads straight for the houses – once there he's safe, for I could send a thousand men in there and he could elude them all.

"They aren't worth the expense of tearing down. And yet they are, if not a menace, at least a nuisance. We should get rid of them and fire is the cheapest, quickest way. We'd use all precautions."

'What about the legal angle?" asked the mayor.

"I checked into that. A man has a right to destroy his own property in any way he may see fit so long as it endangers no one else's. The same law, I suppose, would apply to a municipality."

Alderman Thomas Griffin sprang to his feet.

"You'd alienate a lot of people," he declared. "You'd be burning down a lot of old homesteads. People still have some sentimental attachments-"

"If they cared for them," snapped the chief, "why didn't they pay the taxes, and take care of them? Why did they go running off to the country, just leaving the houses standing. Ask Webster here. He can tell you what success he had trying to interest the people in their ancestral homes."

"You're talking about that Old Home Week farce," said Griffin. "It failed. Of course, it failed. Webster spread it on so thick that they gagged on it. That's what a Chamber of Commerce mentality always does."

Alderman Forrest King spoke up angrily. "There's nothing wrong with a Chamber of Commerce, Griffin. Simply because you failed in business is no reason..."

Griffin ignored him. "The day of high pressure is over, gentlemen. The day of high pressure is gone forever. Ballyhoo is something that is dead and buried.

"The day when you could have tall-corn days or dollar days or dream up some fake celebration and deck the place up with bunting and pull in big crowds that were ready to spend money is past these many years. Only you fellows don't seem to know it.

"The success of such stunts as that was its appeal to mob psychology and civic loyalty. You can't have civic loyalty with a city dying on its feet. You can't appeal to mob psychology when there is no mob-when every man, or nearly every man has the solitude of forty acres."

"Gentlemen," pleaded the mayor. "Gentlemen, this is distinctly out of order."

King sputtered into life, walloped the table.

"No, let's have it out. Webster is over there. Perhaps he can tell us what he thinks."

Webster stirred uncomfortably. "I scarcely believe," he said, "I have anything to say."

"Forget it," snapped Griffin and sat down.

But King still stood, his face crimson, his mouth trembling with anger.

"Webster!" he shouted.

Webster shook his head. "You came here with one of your big ideas," shouted King. "You were going to lay it before the council. Step up, man, and speak your piece."

Webster rose slowly, grim-lipped.

"Perhaps you're too thick-skulled," he told King, "to know why I resent the way you have behaved."

King gasped, then exploded. "Thick-skulled! You would say that to me. We've worked together and I've helped you. You've never called me that before... you've-"

"I've never called you that before," said Webster levelly. "Naturally not. I wanted to keep my job."

"Well, you haven't got a job," roared King. "From this minute on, you haven't got a job."

"Shut up," said Webster.

King stared at him, bewildered, as if someone had slapped him across the face.

"And sit down," said Webster, and his voice bit through the room like a sharp-edged knife.

King's knees caved beneath him and he sat down abruptly. The silence was brittle.

"I have something to say," said Webster. "Something that should have been said long ago. Something all of you should hear. That I should be the one who would tell it to you is the one thing that astounds me. And yet, perhaps, as one who has worked in the interests of this city for almost fifteen years, I am the logical one to speak the truth.