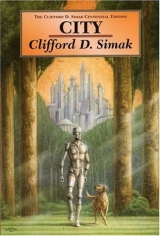

Текст книги "City"

Автор книги: Clifford D. Simak

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

And there were the psychological factors. The psychological factor of tradition which bore like a weight upon the minds of the men who had been left behind. The psychological factor of Juwainism which forced men to be honest with themselves and others, which forced men to perceive at last the hopelessness of the things they sought to do. Juwainism left no room for false courage. And false, foolhardy courage that didn't know what it was going up against was the one thing the five thousand needed most.

What they did suffered by comparison with what had been done before and at last they came to know that the human dream of millions was too vast a thing for five thousand to attempt.

Life was good. Why worry? There was food and clothes and shelter, human companionship and luxury and entertainment – there was everything that one could ever wish.

Man gave up trying. Man enjoyed himself. Human achievement became a zero factor and human life a senseless paradise.

***

Webster took off the cap again, reached out and clicked off the writer.

If someone would only read it once I get it done, he thought. If someone would read and understand. If someone could realize where human life is going.

I could tell them, of course. I could go out and buttonhole them one by one and hold them fast until I told them what I thought. And they would understand, for Juwainism would make them understand. But they wouldn't pay attention. They'd tuck it all away in the backs of their brains somewhere for future reference and they'd never have the time or take the trouble to drag it out again.

They'd go on doing the foolish things they're doing, following the footless hobbies they have taken up in lieu of work. Randall with his crew of zany robots going around begging to be allowed to re-design his neighbours' homes. Ballentree spending hours on end figuring out new alcoholic mixtures. Yes, and Jon Webster wasting twenty years digging into the history of a single city.

***

A door creaked faintly and Webster swung around. The robot cat-footed into the room.

"Yes, what is it, Oscar?"

The robot halted, a dim figure in the half-light of the dusk-filled room.

"It's time for dinner, sir. I came to see-"

"Whatever you can think up," said Webster. "And, Oscar, you can lay the fire."

"The fire is laid, sir."

Oscar stalked across the room, bent above the fireplace. Flame flickered in his hand and the kindling caught.

Webster, slouched in his chair staring at the flames crawling up the wood, heard the first, faint hiss and crackle of the wood, the suction mumble at the fireplace throat.

"It's pretty, sir," said Oscar.

"You like it, too?"

"Indeed I do."

"Ancestral memories," said Webster soberly. "Remembrance of the forge that made you."

"You think so, sir?" asked Oscar.

"No, Oscar, I was joking. Anachronisms, that's what you and I are. Not many people have fires these days. No need for them. But there's something about them, something that is clean and comforting."

He stared at the canvas above the mantelpiece, lighted now by the flare of burning wood. Oscar saw his stare.

"Too bad about Miss Sara, sir."

Webster shook his head. "No, Oscar, it was something that she wanted. Like turning off one life and starting on another. She will lie up there in the Temple, asleep for years, and she will live another life. And this one, Oscar, will be a happy life. For she would have it planned that way."

His mind went back to other days in this very room.

"She painted that picture, Oscar," he said. "Spent a long time at it, being very careful to catch the thing she wanted to express. She used to laugh at me and tell me I was in the painting, too."

"I don't see you, sir," said Oscar.

"No. I'm not. And yet, perhaps, I am. Or part of me. Part of what and where I came from. That house in the painting, Oscar, is the Webster House in North America. And I am a Webster. But a long ways from the house – a long ways from the men who built that house."

"North America's not so far, sir."

"No," Webster told him. "Not so far in distance. But far in other ways."

He felt the warmth of the fire steal across the room and touch him.

Far. Too far – and in the wrong direction.

The robot moved softly, feet padding on the rug, leaving the room.

She worked a long time, being very careful to catch the thing she wanted to express.

And what was that thing? He had never asked her and she had never told him. He had always thought, he remembered, that it probably had been the way the smoke streamed, wind whipped across the sky, the way the house crouched against the ground, blending in with the trees and grass, huddled against the storm that walked above the land.

But it may have been something else. Some symbolism. Something that made the house synonymous with the kind of men who built it.

He got up and walked closer, stood before the fire with head tilted back. The brush strokes were there and the painting looked less a painting than when viewed from the proper distance. A thing of technique, now. The basic strokes and shadings the brushes had achieved to create illusion.

Security. Security by the way the house stood foursquare and solid. Tenacity by the way it was a part of the land itself. Sternness, stubbornness and a certain bleakness of the spirit.

She had sat for days on end with the visor beamed on the house, sketching carefully, painting slowly, often sitting and watching and doing nothing at all. There had been dogs, she said, and robots, but she had not put them in, because all she wanted was the house. One of the few houses left standing in the open country. Through centuries of neglect, the others had fallen in, had given the land back to the wilderness.

But there were dogs and robots in this one. One big robot, she had said, and a lot of little ones.

Webster bad paid no attention – he had been too busy.

He swung around, went back to the desk again.

Queer thing, once you came to think of it. Robots and dogs living together. A Webster once had messed around with dogs, trying to put them on the road to a culture of their own, trying to develop a dual civilization of man and dog.

Bits of remembrance came to him – tiny fragments, half recalled, of the legends that had come down the years about the Webster House. There had been a robot named Jenkins who had served the family from the very first. There had been an old man sitting in a wheel chair on the front lawn, staring at the stars and waiting for a son who never came. And a curse had hung above the house, the curse of having lost to the world the philosophy of Juwain.

The visor was in one corner of the room, an almost forgotten piece of furniture, something that was scarcely used. There was no need to use it. All the world was here in the city of Geneva.

Webster rose, moved towards it, stopped and thought. The dial settings were listed in the log book, but where was the log book? More than likely somewhere in his desk.

He went back to the desk, started going through the drawers. Excited now, he pawed furiously, like a terrier digging for a bone.

Jenkins, the ancient robot, scrubbed his metallic chin with metallic fingers. It was a thing he did when be was deep in thought, a meaningless, irritating gesture he had picked up from long association with the human race.

His eyes went back to the little black dog sitting on the floor beside him.

"So the wolf was friendly," said Jenkins. "Offered you the rabbit."

Ebenezer jigged excitedly upon his bottom. "He was one of them we fed last winter. The pack that came up to the house and we tried to tame them."

"Would you know the wolf again'?"

Ebenezer nodded. "I got his scent," he said. "I'd remember him."

Shadow shuffled his feet against the floor. "Look, Jenkins, ain't you going to smack him one? He should have been listening and he ran away. He had no business chasing rabbits-"

Jenkins spoke sternly. "You're the one that should get the smacking, Shadow. For your attitude. You are assigned to Ebenezer, you should be part of him. You aren't an individual. You're just Ebenezer's hands. If he had hands, he'd have no need of you. You aren't his mentor nor his conscience. Just his hands. Remember that."

Shadow shuffled his feet rebelliously. "I'll run away," he said.

"Join the wild robots, I suppose," said Jenkins. Shadow nodded. "They'd be glad to have me. They're doing things. They need all the help that they can get."

"They'd bust you up for scrap," Jenkins told him sourly. "You have no training, no abilities that would make you one of them."

He turned to Ebenezer. "We have other robots." Ebenezer shook his head. "Shadow is all right. I can handle him. We know one another. He keeps me from getting lazy, keeps me on my toes."

"That's fine," said Jenkins. "You two run along. And if you ever happen to be out chasing rabbits, Ebenezer, and run into this wolf again, try to cultivate him."

The rays of the westering sun were streaming through the windows, touching the age – old room with the warmth of a late spring evening.

Jenkins sat quietly in the chair, listening to the sounds that came from outside – the tinkle of cowbells, the yapping of the puppies, the ringing thud of an axe splitting fireplace logs.

Poor little fellow, thought Jenkins. Sneaking out to chase a rabbit when he should have been listening. Too far – too fast. Have to watch that. Have to keep them from breaking down. Come fall and we'll knock off work for a week or two and have some coon hunts. Do them a world of good.

Although there'd come a day when there'd be no coon hunts, no rabbit chasing – the day when the dogs finally had tamed everything, when all the wild things would be thinking, talking, working beings. A wild dream and a far one – but, thought Jenkins, no wilder and no farther than some of the dreams of man.

Maybe even better than the dreams of man, for they held none of the ruthlessness that the human race had planned, aimed at none of the mechanistic brutality the human race had spawned. A new civilization, a new culture, a new way of thought. Mystic, perhaps, and visionary, but so had man been visionary. Probing into mysteries that man had brushed by as unworthy of his time, as mere superstition that could have no scientific basis.

Things that go bump in the night. Things that prowl around a house and the dogs get up and growl and there are no tracks in the snow. Dogs howling when someone dies.

The dogs knew. The dogs had known long before they had been given tongues to talk, contact lenses to read. They had not come along the road as far as men – they were not cynical and skeptic. They believed the things they heard and sensed. They did not invent superstition as a form of wishful thinking, as a shield against the things unseen.

Jenkins turned back to the desk again, picked up the pen, bent above the note-book in front of him. The pen screeched as he pushed it along.

***

Ebenezer reports friendliness in wolf. Recommend council detach Ebenezer from listening and assign him to contact the wolf.

***

Wolves, mused Jenkins, would be good friends to have. They'd make splendid scouts. Better than the dogs. Tougher, faster, sneaky. They could watch the wild robots across the river and relieve the dogs. Could keep an eye on the mutant castles.

Jenkins shook his head. Couldn't trust anyone these days. The robots seemed to be all right. Were friendly, dropped in at times, helped out now and then. Real neighbourly, in fact. But you never knew. And they were building machines.

The mutants never bothered anyone, were scarcely seen, in fact. But they had to be watched, too. Never knew what devilment they might be up to. Remember what they'd done to man. That dirty trick with Juwainism, handing it over at a time when it would doom the race.

Men. They were gods to us and now they're gone. Left us on our own. A few in Geneva, of course, but they can't be bothered, have no interest in us.

He sat in the twilight, thinking of the whiskies he had carried, of the errands he had run, of the days when Websters had lived and died within these walls.

And now – father confessor to the dogs. Cute little devils and bright and smart – and trying hard.

***

A bell buzzed softly and Jenkins jerked upright in his seat. It buzzed again and a green light winked on the televisor. Jenkins came to his feet, stood unbelieving, staring at the winking light.

Someone calling!

Someone calling after almost a thousand years!

He staggered forward, dropped into the chair, reached out with fumbling fingers to the toggle, tripped it over.

The wall before him melted away and he sat facing a man across a desk. Behind the man the flames of a fireplace lighted up a room with high, stained-glass windows.

"You're Jenkins," said the man and there was something in his face that jerked a cry from Jenkins.

"You... you-"

"I'm Jon Webster," said the man.

Jenkins pressed his hands flat against the top of the televisor, sat straight and stiff, afraid of the unrobotlike emotions that welled within his metal being.

"I would have known you anywhere," said Jenkins. "You have the look of them. I should recognize one of you. I worked for you long enough. Carried drinks and... and-"

"Yes, I know," said Webster. "Your name has come down with us. We remembered you."

"You are in Geneva, Jon?" And then Jenkins remembered. "I meant, sir."

"No need of it," said Webster. "I'd rather have it Jon. And, yes, I'm in Geneva. But I'd like to see, you. I wonder if I might."

"You mean come out here?" Webster nodded.

"But the place is overrun with dogs, sir."

Webster grinned. "The talking dogs?" he asked.

"Yes," said Jenkins. "and they'll be glad to see you. They know all about the family. They sit around at night and talk themselves to sleep with stories from the old days and... and-"

"What is it, Jenkins?"

"I'll be glad to see you, too. It has been so lonesome!"

***

God had come.

Ebenezer shivered at the thought, crouching in the dark. If Jenkins knew I was here, he thought, he'd whale my hide for fair. Jenkins said we were to leave him alone, for a while, at least.

Ebenezer crept forward on fur-soft pads, sniffed at the study door. And the door was open – open by the barest crack!

He crouched on his belly, listening, and there was not a thing to hear. Just a scent, an unfamiliar, tangy scent that made the hair crawl along his back in swift, almost unbearable ecstasy.

He glanced quickly over his shoulder, but there was no movement. Jenkins was out in the dining-room, telling the dogs how they must behave, and Shadow was off somewhere tending to some robot business.

Softly, carefully, Ebenezer pushed at the door with his nose and the door swung wider. Another push and it was half open.

The man sat in front of the fireplace, in the easy-chair, long legs crossed, hands clasped across his stomach.

Ebenezer crouched tighter against the floor, a low involuntary whimper in his throat.

At the sound Jon Webster jerked erect.

"Who's there?" he asked.

Ebenezer froze against the floor, felt the pumping of his heart jerking at his body.

"Who's there?' Webster asked once more and then he saw the dog.

His voice was softer when he spoke again. "Come in, feller. Come on in."

Ebenezer did not stir.

Webster snapped his fingers at him. "I won't hurt you. Come on in. Where are all the others?"

Ebenezer tried to rise, tried to crawl along the floor, but his bones were rubber and his blood was water. And the man was striding towards him, coming in long strides across the floor.

He saw the man bending over him, felt strong hands beneath his body; knew that he was being lifted up. And the scent that he had smelled at the open door – the overpowering god-scent – was strong within his nostrils.

The hands held him tight against the strange fabric the man wore instead of fur and a voice crooned at him – not words, but comforting.

"So you came to see me," said Jon Webster. "You sneaked away and you came to see me."

Ebenezer nodded weakly. "You aren't angry, are you? You aren't going to tell Jenkins?"

Webster shook his head. "No, I won't tell Jenkins."

He sat down and Ebenezer sat in his lap, staring at his face – a strong, lined face with the lines deepened by the flare of the flames within the fireplace.

Webster's hand came up and stroked Ebenezer's head and Ebenezer whimpered with doggish happiness.

"It's like coming home," said Webster and he wasn't talking to the dog. "It's like you've been away for a long, long time and then you come home again. And it's so long you don't recognize the place. Don't know the furniture, don't recognize the floor plan. But you know by the feel of it that it's an old familiar place and you are glad you came."

"I like it here," said. Ebenezer and he meant Webster's lap, but the man misunderstood.

"Of course, you do," he said. "It's your home as well as mine. More your home, in fact, for you stayed here and took care of it while I forgot about it."

He patted Ebenezer's head and pulled Ebenezer's ears.

"What's your name?" he asked.

"Ebenezer."

"And what do you do, Ebenezer?"

"I listen."

"You listen?"

"Sure, that's my job. I listen for the cobblies."

"And you hear the cobblies?"

"Sometimes. I'm not very good at it. I think about chasing rabbits and I don't pay attention."

"What do cobblies sound like?"

"Different things. Sometimes they walk and other times they just go bump. And once in a while they talk. Although oftener, they think,"

"Look here, Ebenezer, I don't seem to place these cobblies."

"They aren't any place," said Ebenezer. "Not on this earth, at least."

"I don't understand."

"Like there was a big house," said Ebenezer. "A big house with lots of rooms. And doors between the rooms. And if you're in one room, you can hear whoever's in the other rooms, but you can't get to them."

"Sure you can," said Webster. "All you have to do is go through the door."

"But you can't open the door," said Ebenezer. "You don't even know about the door. You think this one room you're in is the only room in all the house. Even if you did know about the door you couldn't open it."

"You're talking about dimensions."

Ebenezer wrinkled his forehead in worried thought. "I don't know that word you said, dimensions. What I told you was the way Jenkins told it to us. He said it wasn't really a house and it wasn't really rooms and the things we heard probably weren't like us."

Webster nodded to himself. That was the way one would have to do. Have to take it easy. Take it slow. Don't confuse them with big names. Let them get the idea first and then bring in the more exact and scientific terminology. And more than likely it would be a manufactured terminology. Already there was a coined word– Cobblies – the things behind the wall, the things that one hears and cannot identify – the dwellers in the next room.

Cobblies.

The cobblies will get you if you don't watch out.

That would be the human way. Can't understand a thing. Can't see it. Can't test it. Can't analyse it. O.K., it isn't there. It doesn't exist. It's a ghost, a goblin, a cobbly.

The cobblies will get you

It's simpler that way, more comfortable. Scared? Sure, but you forget it in the light. And it doesn't plague you, haunt you. Think hard enough and you wish it away. Make it a ghost or goblin and you can laugh at it – in the daylight.

***

A hot, wet tongue rasped across Webster's chin and Ebenezer wriggled with delight.

"I like you," said Ebenezer. "Jenkins never held me this way. No one's ever held me this way."

"Jenkins is busy," said Webster.

"He sure is," agreed Ebenezer. "He writes things down in a book. Things that us dogs hear when we are listening and things that we should do."

"You've heard about the Websters?" asked the man.

"Sure. We know all about them. You're a Webster. We didn't think there were any more of them."

"Yes, there is," said Webster. "There's been one here all the time. Jenkins is a Webster."

"He never told us that."

"He wouldn't."

The fire had died down and the room had darkened. The sputtering flames chased feeble flickers across the walls and floor.

And something else. Faint rustlings, faint whisperings, as if the very walls were talking. An old house with long memories and a lot of living tucked within its structure. Two thousand years of living. Built to last and it had lasted. Built to be a home and it still was a home – a solid place that put its arms around one and held one close and warm, claimed one for its own.

Footsteps walked across his brain-footsteps from the long ago, footsteps that had been silenced to the final echo centuries before The walking of the Websters. Of the ones that went before me, the ones that Jenkins waited on from their day of birth to the hour of death.

History. Here is history. History stirring in the drapes and creeping on the floor, sitting in the corners, watching from the wall. Living history that a man can feel in the bones of him and against his shoulder blades – the impact of the long dead eyes that come back from the night.

Another Webster, eh? Doesn't look like much. Worthless. The breed's played out. Not like we were in our day. Just about the last of them.

Jon Webster stirred. "No, not the last of them," he said.

"I have a son."

Well, it doesn't make much difference. He says he has a son. But he can't amount to much

Webster started from the chair, Ebenezer slipping from his lap.

"That's not true," cried Webster. "My son-"

And then sat down again.

His son out in the woods with bow and arrows, playing a game, having fun.

A hobby, Sara had said before she climbed the hill to take a hundred years of dreams.

A hobby. Not a business. Not a way of life. Not necessity.

A hobby...

An artificial thing. A thing that had no beginning and no end. A thing a man could drop at any minute and no one would ever notice.

Like cooking up recipes for different kinds of drinks.

Like painting pictures no one wanted.

Like going around with a crew of crazy robots begging people to let you redecorate their homes.

Like writing history no one cares about.

Like playing Indian or caveman or pioneer with bow and arrows.

Like thinking up centuries-long dreams for men and women who are tired of life and yearn for fantasy.

The man sat in the chair, staring at the nothingness that spread before his eyes, the dread and awful nothingness that became to-morrow and to-morrow.

Absent– mindedly his hands came together and the right thumb stroked the back of the left hand.

Ebenezer crept forward through the fire-flared darkness, put his front paws on the man's knee and looked into his face.

"Hurt your hand?" he asked.

"Hurt your hand? You're rubbing it."

Webster laughed shortly. "No, just warts." He showed them to the dog.

"Gee, warts!" said Ebenezer. "You don't want them, do you?"

"No," Webster hesitated. "No, I guess I don't. Never got around to having them taken off."

Ebenezer dropped his nose and nuzzled the back of Webster's hand.

"There you are," he announced triumphantly.

"There I'm what?"

"Look at the warts," invited Ebenezer.

A log fell in the fire and Webster lifted his hand, looked at it in the flare of light.

The warts were gone. The skin was smooth and clean.

***

Jenkins stood in the darkness and listened to the silence, the soft sleeping silence that left the house to shadows, to the half-forgotten footsteps, the phrase spoken long ago, the tongues that murmured in the walls and rustled in the drapes.

By a single thought the night could have been as day, a simple adjustment in his lenses would have done the trick, but the ancient robot left his sight unchanged. For this was the way he liked it, this was the hour of meditation, the treasured time when the present sloughed away and the past came back and lived.

The others slept, but Jenkins did not sleep. For robots never sleep. Two thousand years of consciousness, twenty centuries of full time unbroken by a single moment of unawareness.

A long time, thought Jenkins. A long time, even for a robot. For even before man had gone to Jupiter most of the older robots had been deactivated, had been sent to their death in favour of the newer models. The newer models that looked more like men, that were smoother and more sightly, with better speech and quicker responses within their metal brains.

But Jenkins had stayed on because he was an old and faithful servant, because Webster House would not have been home without him.

"They loved me," said Jenkins to himself. And the three words held deep comfort – comfort in a world where there was little comfort, a world where a servant had become a leader and longed to be a servant once again.

He stood at the window and stared out across the patio to the night-dark clumps of oaks that staggered down the hill.

Darkness. No light anywhere. There had been a time when there had been lights. Windows that shone like friendly beams in the vast land that lay across the river.

But man had gone and there were no lights. The robots needed no lights, for they could see in darkness, even as Jenkins could have seen, had he but chosen to do so. And the castles of the mutants were as dark by night as they were fearsome by day.

Now man had come again, one man. Had come, but he probably wouldn't stay. He'd sleep for a few nights in the great master bedroom on the second floor, then go back to Geneva. He'd walk the old forgotten acres and stare across the river and rummage through the books that lined the study wall, then he would up and leave.

Jenkins swung around. Ought to see how he is, he thought. Ought to find if he needs anything. Maybe take him up a drink, although I'm afraid the whisky is all spoiled. A thousand years is a long time for a bottle of good whisky.

He moved across the room and a warm peace came upon him, the close and intimate peacefulness of the old days when he had trotted, happy as a terrier, on his many errands.

He hummed a snatch of tune in minor key as he headed for the stairway .

He'd just look in and if Jon Webster were asleep, he'd leave, but if he wasn't, he'd say: "Are you comfortable, sir? Is there anything you wish? A hot toddy, perhaps?"

And he took two stairs at the time.

For he was doing for a Webster once again.

***

Jon Webster lay propped in bed, with the pillows piled behind him. The bed was hard and uncomfortable and the room was close and stuffy – not like his own bedroom back in Geneva, where one lay on the grassy bank of a murmuring stream and stared at the artificial stars that glittered in an artificial sky. And smelled the artificial scent of artificial lilacs that would go on blooming longer than a man would live. No murmur of a hidden waterfall, no flickering of captive fireflies – but a bed and room that were functional.

Webster spread his hands flat on his blanket covered thighs and flexed his fingers, thinking.

Ebenezer had merely touched the warts and the warts were gone. And it had been no happenstance – it had been intentional. It had been no miracle, but a conscious power. For miracles sometimes fail to happen, and Ebenezer had been sure.

A power, perhaps, that had been gathered from the room beyond, a power that had been stolen from the cobblies Ebenezer listened to.

A laying– on of hands, a power of healing that involved no drugs, no surgery, but just a certain knowledge, a very special knowledge.

In the old dark ages, certain men had claimed the power to make warts disappear, had bought them for a penny, or had traded them for something or had performed other mumbo-jumbo-and in due time, sometimes, the warts would disappear.

Had these queer men listened to the cobblies, too?

The door creaked just a little and Webster straightened suddenly.

A voice came out of the darkness: "Are you comfortable, sir? Is there anything you wish?"

"Jenkins?" asked Webster.

"Yes, sir," said Jenkins.

The dark form padded softly through the door.

"Yes, there's something I want," said Webster. "I want to talk to you."

He stared at the dark, metallic figure that stood beside the bed.

"About the dogs," said Webster.

"They try so hard," said Jenkins. "And it's hard for them. For they have no one, you see. Not a single soul."

"They have you."

Jenkins shook his head. "But I'm not enough, you see. I'm just... well, just a sort of mentor. It is men they want. The need of men is ingrown in them. For thousands of years it has been man and dog. Man and dog, hunting together. Man and dog, watching the herds together. Man and dog, fighting their enemies together. The dog watching while the man slept and the man dividing the last bit of food, going hungry himself so that his dog might eat."

Webster nodded. "Yes, I suppose that is the way it is."

"They talk about men every night," said Jenkins, "before they go to bed. They sit around together and one of the old ones tells one of the stories that have been handed down and they sit and wonder, sit and hope."

"But where are they going? What are they trying to do? Have they got a plan?"

"I can detect one," said Jenkins. "Just a faint glimmer of what may happen. They are psychic, you see. Always have been. They have no mechanical sense, which is understandable, for they have no hands. Where man would follow metal, the dogs will follow ghosts."

"Ghosts?"

"The things you men call ghosts. But they aren't ghosts. I'm sure of that. They're something in the next room. Some other form of life on another plane."

"You mean there may be many planes of life co-existing simultaneously upon Earth?"

Jenkins nodded. "I'm beginning to believe so, sir. I have a note-book full of things the dogs have heard and seen and now, after all these many years, they begin to make a pattern."

He hurried on. "I may be mistaken, sir. You understand I have no training. I was just a servant in the old days, sir. I tried to pick up things after... after Jupiter, but it was hard for me. Another robot helped me make the first little robots for the dogs and now the little ones produce their own kind in the workshop when there are need of more."

"But the dogs – they just sit and listen."

"Oh, no, sir, they do many other things. They try to make friends with the animals and they watch the wild robots and the mutants-"