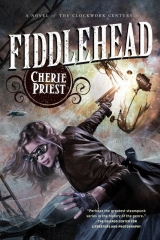

Текст книги "Fiddlehead"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

She blushed, and even the dwindling firelight couldn’t hide it. “Thank you, sir.”

When she was gone, Gideon said to Lincoln through the still-open door, “I’m going to check the other end of the hall, then work my way back. If you have any trouble, fire a warning shot, but fire it into those books. Anywhere else, and it might bounce in this little room.”

“I’m not an idiot, Gideon.”

“I’m only thinking out loud,” he assured him. In the quiet that followed, he really should’ve turned and left; but, like Polly, he found himself reluctant to leave Lincoln alone. “Is there … anything I can get you? Anything you need?”

“I need for my friends to believe I’m still a capable man,” he said. “I will be fine,and so will the rest of you. With you and Grant defending the place, I’m confident that it will stand.”

Gideon wished he hadn’t said that, even if he agreed. “We’ll do our best,” he said, and he stalked off down the hall, praying their best would be enough.

Twenty

“I thought we’d landed closer to the road than this,” Maria grumbled, tripping over a tree root and scraping her already-raw hand against a trunk when she caught herself.

“So did I.” Henry grimaced with pain, so often that it seemed his whole face was set that way in a permanent expression of discomfort. But a broken arm was plenty of excuse, to say nothing of the assorted scrapes, bumps, and bruises that plagued them both.

Maria ached in places she rarely thought of, and she bled from more injuries than she let on. Besides the cut on her head, under her coat she hid a hard puncture that had made it past her corset stays. She didn’t know how deep it went, and she didn’t know what had caused it. Part of the Black Dove,as they’d kicked free of its tumbling wreckage? A tree branch on the way down? Something else, when she’d landed?

The wound was under her rib cage, on the right side. It left a great stain on her dress, so she kept her coat fastened around herself, even tighter than before. Now it wasn’t just the cold. She needed for Henry to believe that she was all right, because if he thought otherwise, he’d attempt to coddle them both and they’d never get anywhere.

Just this once, she was glad for the cold.

It kept her numb enough to keep walking, hiking between the trees and around them. She hoped they were headed in the right direction, but had no way of knowing for certain. She had no compass, only Henry’s gut feeling; and she did her best not to second-guess him, because she had no idea herself.

Finally, they saw a line where the trees thinned. When they stumbled up out of the woods, they found themselves on a road. It amounted to little more than four sets of ruts in places, but the rain that season had been bad, and it was no secret that the Confederacy was low on money. Public works were suffering along with everything else.

No other vehicles or travelers were present, a fact that bothered Maria. She’d hoped to find carts—of the motorized or horse-drawn variety, she did not care which—and use her wiles to flag one down for a lift. She was exhausted and sore. Henry surely was in no better condition, though he also seemed to be hiding the worst of his pain.

So they trudged forward, southbound and surly, until a benevolent farmer heading in the right direction came along. Maria bribed him with sorrowful eyes, and Henry sealed the deal with the few Confederate coins from his pocket that hadn’t rained across the Georgia countryside as he’d fallen to earth.

The ride was faster than walking, and it gave them time to rest, if not recover.

When the farmer took a turn for the west, he left them on the road and they continued on foot, thankful for the help but wishing for more assistance. It didn’t come.

The day grew later, and the shadows grew longer. Maria didn’t know what they’d do when night fell. They had almost nothing in the way of supplies, much less any source of light, and roaming along a road at night was a surefire way to get robbed or murdered … or so she’d always been told.

She squeezed the battered satchel that still hung around her neck, and yes, her gun was still there. But none of her bullets had survived the trip, so whatever was in the wheel was all she had left. Henry had done better for himself: His shoulder holster was under his coat, and therefore his firearm and supplies had survived the trip more completely.

She doubted their guns would be of much use against the Maynard device, but they made her feel better all the same.

Another hour passed, and her feet were blocks of ice. Her nose had lost all feeling, and her injuries hurt terribly. Henry was flagged as well: His ordinarily fair complexion had gone positively white, his glasses were long gone, and when he wiped at his nose with one torn sleeve, it left a damp, bloody streak on the back of his arm.

And then they heard voices, accompanied by the crush and roll of large wheels on uneven turf. Not far ahead, there were people. Carts. Horses.

And then the dome of the big black cargo dirigible came into view.

Henry stopped and took her arm. “Let’s leave the road. Come around to the side.”

“You want to sneak up on them?”

“I want to watch them before we try to engage. We might learn something. Spot a weak point. If we walk up to them now, they’ll shoot us before we get close.”

She wasn’t so sure, but she didn’t fight him when he led her off the tracks that passed for a highway and back into the trees. They circled quietly around, staying just beyond the clearly visible road, until they were within earshot.

The caravan had stopped. Only a few minutes of eavesdropping told them why.

“God damnthis road! How does anyone ever move anything?”

“There’s not much left to move,” someone said wryly, but not loudly. “The state’s bankrupt—the whole country’s bankrupt. Hell, I’m just I’m glad there’s any road at all. We could be stuck hacking our way through the woods, and then what?”

“Then we’d be stuck in this hellhole forever,” griped someone close. “How are we going to get this thing going again? Frank said we can’t push the crawler’s motor any harder, or we’ll blow it.”

“Then we won’t push the crawler’s motor any harder,” said a new voice—someone who spoke with a commanding bent.

Maria strained to see him, but between the trees she saw nothing but a flash of gray uniform and a shock of hair beneath a cap that looked like it might be red. “There’s the man in charge,” she guessed aloud to Henry, who nodded.

The man in charge said, “We’ll have to dig ourselves out.”

“You’re sure the ship can’t lift us?”

“You saw us try it. Did it work? No? Then yes,I’m sure the ship can’t lift us. We can’t burn through its hydrogen, anyway. Not if we want a way home, when all’s said and done.”

“Sir, we’re … we’re fish in a barrel if we stay in the middle of this road.”

“Heavily armed fish in a military convoy. Pull yourself together, and get a shovel.”

“Do we have shovels?”

“Check with the ship; they might have some. If not, we’ll improvise. We have axes, and we have a whole forest full of wood we can commandeer if we have to. Bring me Lieutenant Engel, and I’ll see what exactly we have at our disposal.”

Henry leaned over and whispered into Maria’s ear. “Maybe we’ll get lucky and he’ll wander away from the caravan. We may have to swipe him, but we’ll make him listen to us.”

“We’re a pitiful pair of kidnappers, you and I.”

“We’re armed. We don’t have to overpower him, just surprise him.”

“Is that our plan?” she asked.

“It’s a possibility. Should we split up?”

She thought about it and said, “We could, but let’s not. We’d just double our chances of getting caught.”

He nodded. “All right. Let’s go together, then.”

Forward they crept, staying low and working toward the giant rolling-crawler—a Texian-made monstrosity that operated on floating axles, and was renowned for its ability to traverse uneven terrain. Apparently it wasn’t quite advanced enough for Georgia roads, which made Maria smile ruefully until she drew near enough to really look at the thing. It was huge—bigger than any such contraption she’d ever seen before, in the North or South. Six wheels on three axles, and about as tall as a single-story building, except for the back portion, which was open like a cart.

This segment was occupied by something huge and—if the set of the wheels in the road was any gauge—quite heavy. The rear half was bogged down, oversized tires lodged into fresh ruts that had been made all the deeper by their spinning, digging, lunging efforts to free the thing.

“Can you see it?” Henry asked, craning his neck.

“They’ve covered it up with something. We’ll have to get closer, though it may be dangerous.”

“We might … not have much choice,” he said slowly, turning his head sharply but carefully to the right.

Maria followed his new gaze, and was horrified to see a gray-dressed soldier with a large army-issue rifle. The rifle was long-barreled with its hardware in gleaming condition, and it was aimed directly at them.

He said, “Hello there. I’d ask what we have here, except I can make myself a guess.”

“It’s not what it looks like,” she promised him.

“It’s not two people spying on a military caravan?” he asked with a smirk.

Maria instantly disliked him, not that there was anything she could do about it. “No, it’s notthat. Not exactly.”

Henry stood up straight from his crouch, and said, “I’m a U.S. Marshal, and I’m here to help. I’m going to get my badge out of my coat, see? I’m not drawing a gun.”

“U.S. Marshal my ass. Don’t you dare move.” Over his shoulder he shouted, “Hey, Captain, I’ve got something over here!”

“What?”

“A couple of spies; come and see ’em,” he called. “One says he’s a marshal.”

“A marshal?”

Seconds later the captain appeared—and, yes, it was the red-haired man they’d identified before, in a well-fitting uniform, as opposed to those of his subordinates. He was handsome in a way that red-haired men tended not to be, in Maria’s experience—though there was always an exception to the rule, and here he was. His eyes were cool, intelligent, and very blue.

Another gray-uniformed man appeared with him, and now they were outnumbered.

“Captain,” Henry said, not bothering to address anyone anymore, except the man who made the decisions. “My name is Henry Epperson and I’m with the U.S. Marshals Service. I was sent here by the president himself, with regards to Project Maynard.”

Maria gave him a bit of side-eye. She wasn’t sure she would’ve played it so on the nose, but between the pair of them, he was the one most likely to be listened to, so she chose to trust him. It was too late to do anything else, anyway.

“The president?” The captain huffed a small, incredulous laugh. “If you’ve got word from President Grant, then why are you sneaking up on us, hiding in the woods? And furthermore, let me see your badge.”

“It’s here in my coat pocket,” he said again, fumbling for it with his good hand, and finding it this time. He tossed it to the captain.

While the captain examined it, Maria answered the rest. “We’re sneaking up on your caravan because the big cargo ship you’re traveling with shot us down a few miles back down the road. You’ll have to forgive us if we weren’t fully committed to approaching you openly—not while that thing docks overhead.”

“Shot you down?” he frowned, and glanced back toward the road. “So that’s what all the commotion was about. We heard it, but couldn’t see it for the trees.” Over the trees they could all see the craft’s dome, bobbing slowly in the dying wind. “Why would they shoot you down? Why would…”

The man obviously had more questions, but maybe he had answers, too—and he didn’t like them much. He tossed the badge back to Henry, who caught it with a fast jab of his hand. “What about you?” he asked. “You’re not a marshal, are you, ma’am?”

“No, sir, I’m not. I’m a Pinkerton agent, hired by Abraham Lincoln. This marshal and I have been working together with regards to this project you’re transporting to Atlanta—and I do note that you didn’t contradict us, or argue, when Henry called it by its proper name. You’re Union soldiers, the lot of you. Blue wearing gray, undertaking a top secret mission to deploy a terrible weapon in Atlanta. You know it. We know it. And the president knows it, too. He’s trying to stop it.”

“Ma’am,” he said, adjusting his hat and shifting his weight. He lowered his voice, but not much. “This project is as top secret as they come, or so we’re told. If you’re Confederate spies, you’re not very good ones—traveling alone and naming names, when you ought to play dumb and ask for help. But your badge looks like the real thing,” he said to Henry, “and if you say the president sent you, then that’s either the stupidest tall tale you could pull out of your ear on a moment’s notice, or it’s the truth.”

Maria wanted to breathe a sigh of relief, but she didn’t dare, not yet. “Captain, we came here to warn you. The project is more dangerous than you know: It’s a suicide mission for you and your men, authorized through unofficial channels, and paid for by a warhawk tycoon with the help of the Secretary of State.”

The captain’s lovely eyes narrowed, and he crossed his arms. “Is that so?”

“Who gave you your orders? And don’t answer me—I’m asking you to ask yourself.Did it come from the top? Or from some underling who professed to speak with presidential authority?”

“The Secretary of State is hardly an underling, really.”

Maria stood to her full height and brushed scraps of forest floor off her battered dress. “He’s an underling to the president,who is scrambling, sir—absolutely scrambling—to put a stop to this project. And if I were to wager a guess, I’d say that his wasn’t the name on your orders. The cargo craft that accompanies you—I saw through their window with a spyglass. They’re Baldwin-Felts agents, hired by this warhawk tycoon.”

“But acting with the authority of…” His voice trailed off as he pondered the implications. The captain’s two juniors exchanged a worried glance, but their officer didn’t take his eyes off Maria, who refused to blink or retreat. “So you two … you’re the ones tasked with the mission of reaching us? And giving us this message?”

Henry responded, “There were half a dozen potential deployment locations, and no one could—or would—say exactly where the weapon was headed. Washington, D.C., is in disarray, Captain. At this time, it stands as divided as the nation. The president wants to bring the war to an end, but he’s being hampered and hindered on all sides by those who would profit from it.”

Again the captain looked up at the cargo dirigible, deliberating. “The men in that ship—they’re Baldwins, you’re right about that. They’re supposed to be our supply and evacuation team.”

“They’re trusting you to civilians?” Maria asked.

To which he replied pointedly, “Last I heard, Pinkertons were civilians as well, ma’am, and you profess to work on behalf of the District yourself. And I don’t believe I caught your name, but I know your accent isn’t any farther north than the line.”

“Maria.” Then she swallowed hard and said, “Maria Boyd. I come from Virginia, but I work from Chicago.”

If he recognized her name, he didn’t react to it. All he said was, “All right, then, Miss Boyd and Mr. Epperson. You know an awful lot about what we’re doing.”

“More than you do,” she said urgently. “Please, you have to listen to us, Captain … Captain, I don’t believe I caught your name, either.”

“MacGruder,” he told her. “I’m commanding officer for this operation, such as it is,” he added unhappily, gazing toward the trapped rolling-crawler.

“Captain MacGruder,” she said, turning the name over in her mouth, feeling the letters tumble together and thinking that it sounded familiar—very familiar—but she couldn’t put her finger on it. Finally, she gave up and asked, “Do you know what the weapon does?”

He hesitated. Maria thought that it must not be that he didn’t know, but that he wasn’t sure how much to tell her. “It’s a bomb. An advanced bomb that will do … untold damage.” He said it like he was confessing to himself. “But it’s a bomb that can end the war, like the president wants—and that is my mission. These are my orders.”

“No, sir, that isn’tyour mission, and your orders were falsified. That weapon is a bomb, yes, and it will do far worse than untold damage—but it won’t end the war, you can safely bet on that. Katharine Haymes is readying herself to make a fortune on a gamble that this bomb works well enough to become the talk of the town, but not well enough to end a goddamn thing.”

“Haymes?” The captain looked startled. “That’s a name I know.”

Henry said, “You ought to. She killed hundreds of Union prisoners at a camp in Tennessee.”

“With gas,” he said thoughtfully. “She did it with gas; I heard about that. I tried to tell people, but they didn’t want to hear it.…”

“Hear what?” Maria asked. “Tell people what?”

He shook his head. “I told my superiors that I’d seen that kind of devastation before. I’d reported it once already … not that anyone listened then, either. What she did, that weapon she tested.… But, wait, I thought she was a Confederate?”

Maria shook her head. “No, she claims no nation. She belongs to whichever side can pay her best, and we both know that means she’s working for the Union now. That thing you accompany, it’s a gas bomb of such a size that it could wipe out half of Atlanta, including whoever’s nearby when it’s released. You’ll never escape it. There won’t be time.”

“But, the cargo ship…” The soldier with the rifle asked the captain, “The ship’ll pull us out, won’t it?”

“How?” Maria demanded, addressing him once more, rather than the handsome captain. “That thing isn’t big enough to hold the lot of you, and someone would have to stay behind and set the bomb off, anyway.”

The captain argued with her, but without much conviction. “We’re going to shoot it from the air. It’s a big enough target. But … I’ve wondered.” Then he muttered, like he couldn’t shake the significance, “If it’s … a gas bomb…”

“And one that doesn’t just kill…” Henry continued.

“It’s the walking plague.” The captain said the words softly, almost under his breath. “It’s a bomb that gives people … that turns them into the living dead. That’s what this is, isn’t it? The walking plague is created by a weapon.”

“Well, yes and no,” Henry said. He might’ve said more—asking how the captain had drawn such a conclusion, correct though it might well be—but at that moment Maria had a revelation.

Two thoughts had been bouncing around in her brain, ever since the captain had identified himself: his name, and where she might’ve heard it before. Those two ideas finally collided, crashing together so that the sparks illuminated the truth. She blurted out, “You’re the Captain MacGruder from the nurse’s notes!”

Everyone froze, mostly from confusion. The captain asked her, “I’m sorry, nurse? What nurse?”

“On the train,” she continued excitedly. “The Dreadnought—you were on the Dreadnought! I read about it!”

He recoiled, stunned. “Read about it? Where on earth could you have read about it? No one’s written about it except for me—and what I wrote went ‘missing,’ according to anyone I asked,” he said angrily. “I tried to tell them! The walking plague doesn’t just walk among soldiers, and it isn’t confined to the front.”

“But it isyou,” Maria persisted. “ Youwere the Union captain the nurse trusted, who survived what happened in Utah. Just admit it!”

“The nurse,” he muttered, flailing to find the context she prodded him for. “There … there wasa nurse, yes. Mercy, that was her name. She … she wrote a book? She’s alive? I tried to find her, but the ranger, the nurse, the Rebs who made it out alive … everyone’s gone. Reassigned, they told me,” he recounted bitterly. “Secret missions. Secrets everywhere, no one talking, no one listening. No one left. All of them, gone.”

“And you’ll be gone, too, if you finish this mission. We all will.”

The forest whistled and shook, as the wind gave one last gasp through the trees, scattering what was left of the leaves and tweaking the brittle branches. No one spoke while they watched the captain reflect, consider, think, and finally … conclude.

He gave a good, hard glare at the cargo ship through the trees and said, “Get me Frankum. I need to speak with him. You two—Miss Boyd, Marshal—come with me. Graham, Simmons, keep an eye on them.”

Maria began to protest. “But we’re—”

“I’m not taking any chances.”

So, at gunpoint, they followed the captain up the side of the hill, onto the road, and into the middle of the caravan—where they were greeted with stares and gossipy whispers.

The captain announced, “Gentlemen, we have guests: a U.S. marshal and a Pinkerton agent, pulled from the woods like foundlings. They were left there courtesy of Captain Frankum, or so they tell me. So, where is our fine, upstanding dirigible pilot, eh?”

Something about his pronunciation of “fine” and “upstanding” implied a keen sense of irony.

Maria and Henry kept close to each other, nearly back-to-back. No one had taken their firearms, which might be construed as a lack of caution on Captain MacGruder’s part, except that they had nowhere to go, and they weren’t likely to stage a gun-blazing escape in their battered state.

“You two, over here,” one of their guards told them, gesturing with the barrel of his gun. He guided them to the big rolling-crawler, and suggested they should stand against it and wait for further instructions. “Captain? Where are you going?”

“I’ll be back in a minute,” he answered vaguely, and stomped off to the far edge of the convoy, where Maria could no longer see him.

She didn’t like it, and Henry didn’t, either, but they did as they were told. They put their backs to the thing and tried not to think about what was inside it, now only inches from their bodies. Maria fancied that she could hear a hum, some strained, coursing sound from within. She could feel it better than she could hear it, as the vibrations rattled at her ribs. It was almost as if the bomb were a living thing, with pulse and respiration and a sense of urgency—an awful destiny that it wanted to fulfill.

Maria banished her imagination’s wanderings and closed her eyes, exhausted. She wanted to sit down, but she couldn’t bring herself to do so, not while so much danger remained … and she didn’t know what form it was likely to take, or even where it might come from.

But she was so, so tired. And so very sore. And she so very badly wanted to sleep.

Eventually, Captain Frankum appeared in their midst, joined by two of his fellow airmen. The captain himself was a short, sturdy man without an ounce of fat on him, but a squared-off appearance that indicated a great deal of muscle. He was no more handsome or friendly looking up close than he had been in the clouds, nor were either of his men.

Captain MacGruder also returned from whatever errand he’d wandered off to. His face was set in a firm expression, all business and ready for conflict—an effect that was slightly undone, in Maria’s opinion, by the pink flush across his nose, brought on by the cold.

“Frankum, there you are. I’ve got a question for you,” he said.

At approximately that precise moment, Frankum noticed the newcomers. At first, his eyes glanced past them, but he did flash a quick second look at Maria. It could’ve meant anything: He might have recognized her from the sky, or maybe he was only confused at seeing a woman there.

“Who are they?” the Baldwin-Felts man asked.

Captain MacGruder feigned innocence. “You don’t know?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Then why’d you shoot them down a few hours ago?”

“Why did I…?”

“You heard me,” MacGruder said, coming in closer. He leaned forward, craning over the shorter man and casting a shadow over him. “Why did you shoot them down? What we have here, Captain”—spitting out the word like it tasted bad—“is a U.S. Marshal and another agent, sent as messengers from the White House.”

Maria appreciated that he’d left out the “Pinkerton” part, given how little love was lost between the two firms. It meant he was thoughtful for her safety, perhaps; or it meant that he was smart, and didn’t feel like adding the extra trouble to the mix.

“A marshal? Why would the president send a marshal?” Frankum tried to redirect the inquiry, but he didn’t do it smoothly—and before the crisis could be forced any further, he gave up the pretense of innocence. “I didn’t have any way of knowing who they were. Besides, you have your orders, I have mine. Mine say to keep all crafts away from this convoy, and I was doing my job.”

“Mr. Epperson,” Captain MacGruder said to Henry, but kept his eyes on Frankum. “Were you flying in a federal craft? Did you make any attempt to identify yourself?”

“A federal craft in Confederate airspace? No,for Christ’s sake. And we weren’t given the opportunity to identify ourselves; we were attacked without warning upon approach.”

Frankum flashed a quick glance at the sky. Then, as if it had just occurred to him, he asked, “Wait a minute. Where’s Kramer?”

“Kramer?” Henry echoed.

“Captain Kramer,” Frankum said crossly. “He was following us out, in his little supply ship. He stayed behind us; he was supposed to…”

“To what?” Maria demanded. “Kill us? Shoot us down? I hate to disappoint you—or, rather, I don’t mind it in the slightest: We survived that encounter somewhat more cleanly than we survived our dustup with your craft. The ashes of that other ship are, at present, raining down softly over Georgia.” She added a fluttering motion with her numb, bruised fingers for emphasis.

“You took it down? In your little two-seater?”

“She’s a mighty good shot.” Henry was exaggerating, but Maria was pleased nonetheless.

“Look, look, look.” Frankum held out his hands, both attempting to defend himself and shush everyone else. “What I want to know is, how do we know these two came from the District? And why are you so fast to assume they’re telling the truth? You’re just going to let them waltz out of the woods and derail this operation? This very expensiveoperation, months in the planning? I don’t guess they had anything with the presidential seal on them?”

Henry said, “No, but—”

“So we take their words for it? Blow the whole mission, on the word of two spies?”

“We aren’t—”

But MacGruder interrupted, “No, I’m not willing to blow the whole mission. But I am willing to delay it a bit. I don’t even have much choice, given that we still have to extract this damn thing from the road,” he said, scowling at the rolling-crawler. “Texian technology … you’d think it could handle a Southern road. Jesus.Anyway, since we’ve got a minute, I just now put Bradley on a fast horse to Atlanta, to the taps there.”

“But the taps are down, all over the place,” the air captain argued.

“Yes, but if they’re up again anywhere, they’ll be up in the city. We’ll just take a break and ask the president ourselves what he wants us to do.”

“But, but, that’ll take hours!” Frankum sputtered. “And you can’t just send the president a note and wait for orders—you already haveorders!”

“And I’m following them, until I hear differently,” MacGruder said coolly. “But it’ll take an hour or more to get this damn cart dug out, and once we’re back on the road—well, at our pace we’re lucky if it’s another four hours to the city. Bradley ought to catch us before we reach it, and we can reevaluate the matter depending on what he says.”

Frankum stayed calm, but his men were getting antsy. Maria watched them fidget and exchange nervous glances, though their captain’s expression was a fierce threat to maintain their composure. The man to his left lost it first. He asked, “Hours?”

The word was small, but it was almost too frightened to be heard.

“Hours,” MacGruder nodded.

“We don’t havehours.”

“Shut up,” Frankum said to his man. Then, to MacGruder, “Hours aren’t in the plan, and you know it.”

“Plans change.”

“You’re stalling.”

“I am stalled,” Captain MacGruder declared. “And what does it matter if we reach Atlanta come sundown? The city will go to hell as easily at dusk as midday.”

Frankum shook his head, and his eyes darted back and forth between his crewmen. “We were supposed to be there by now. We should’ve been halfway back to the Mason-Dixon by now.”

“Plans change. We adapt. Without flexibility, we’re all doomed to fail.”

“ I’mnot,” Frankum insisted. “And I have obligations elsewhere. I don’t have to hover with you fools while you get your act together.” He snapped his fingers, and pointed at the cargo craft. “You two, get back in the ship. We’re taking off.”

“No, you’re not,” MacGruder said, flatly.

“We need more hydrogen; we’ve burned off too much sitting around waiting for your men to fix this. If we don’t go get more, we won’t have enough to pick you up and get us all clear of the blast.”

“You’re not leaving this caravan until everybody leaves it.”

Maria saw an opportunity to deepen the wedge between them, and she seized it. “That was never part of the plan,” she blurted out. All eyes turned to her, so she said it again. “It was never part of the plan for anyof you to survive the trip.”

MacGruder came forward, until he stood directly in front of her. “Out in the woods you said this was a suicide mission for me and my men.”

“That’s right. That’s one reason the president rejected the program.”

“There were others?”

“Once he learned what the weapon really does, yes. President Grant doesn’t want to create a legion of walking dead men any more than you do.”

As she spoke, Frankum and his men began a slow retreat, designed to keep from attracting too much attention.

It didn’t work. MacGruder’s men stopped them with rifles primed, promising violence if anyone tried to leave the area. The captain himself whirled around on one heel, stomped up to Frankum, and seized him by the collar. He dragged the pilot off his feet, pulling him forward, and slamming him up against the nearest cart.

Frankum’s eyes bugged out, darting frantically back and forth. He sought his men but found only MacGruder’s face wearing a very big frown.

“Is she telling the truth? Were you supposed to leave us here?”