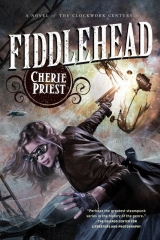

Текст книги "Fiddlehead"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанры:

Классическое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Nelson Wellers wrung his slim hands together and swallowed, then ran his fingers through his hair. “He was with mewhen the murders were committed. He has an alibi.”

“Yes,” Gideon said it fast, as the puzzle piece fell into place. “Yes, that’s true. From a doctor and an agent of the law, after a fashion. We can prove I’ve done no wrong. I should’ve let them arrest me!”

“Gideon, no.You were right to slip away while you could. I sensed it the moment they arrived. They didn’t want to interview me, or have me offer any statement on your behalf. And when they realize that I can vouch for you, they’ll come for me. I…” He looked around, his gaze darting from corner to corner. “I shouldn’t stay here. I’m a danger to you all.”

“Wellers, settle down,” Gideon groused. “No one’s coming for you. I’m the problem here. if anyone should go, it ought to be me.”

“But I’m willing and ready to plead your case and take the stand on your behalf. That’swhy they’ll need to be rid of me. If they kill Gideon,” Wellers said sharply to Lincoln, “they make him a martyr—they make his message louder. But if they kill me, he has no defense and he’ll be shrieking his message from a jail cell, like a madman. I need to send a message to Chicago. I need to summon a replacement.”

“You’re abandoning us?” Gideon asked with disbelief.

“No. Absolutely not. But I can’t speak on your behalf if I’m dead, and I won’t stand for anyone else getting caught in the fray. Certainly not you, or Mary or Polly,” he said firmly to the old man.

“Now don’t say anything rash. Furthermore, don’t doanything rash,” Lincoln said in a calming voice. “They can’t kill us all. They won’tkill us all, even if they catch us. The police won’t be back for another hour or two, I shouldn’t think; and although Haymes has agents who are willing to break the law, they may not have arrived yet, and surelythey won’t come for you here. Not yet. Not yet.” He murmured the words like a mantra. “We have time to think. Time to plan for—”

He was interrupted by a knock on the door, hard and fast, a steady bang of the metal ring.

All three men froze in place, exchanging a violent lightning of glances.

The doctor said, “Gideon, hide.”

And Gideon said, “ No.”

“No one’s hiding, not yet,” Lincoln said, his timbre a plea for patience and order. It was a plea for time, but even that great man couldn’t wring more from the moment than was already granted.

Down the hall a man came running, all heavy footsteps and rambling, long-legged pace; and behind him trailed the lighter, frantic footsteps of the serving girl. In the library, all three men drew guns, prompting Gideon to wonder where Lincoln had hidden one, and how he used one with those twisted fingers.

He analyzed the situation with his ears.

Polly’s following behind him, whoever he is. He didn’t break inside, he knocked. He is alone except for the girl, who can’t catch up to him. This might not be what it sounds like.

“Abe!” the newcomer shouted before he reached the library. That one word blew the tension from the room like steam through a kettle whistle.

“Grant?” the old president asked, just in time to spy the leader flinging himself around the doorjamb.

“Abe, they’ve killed…” He stopped when he saw Gideon and Nelson, who lowered their guns but did not put them away.

“I know,” Lincoln told him. “Your housemaster, and his wife, and the girl who stole those papers. I got your message half an hour ago, and I’m very sorry to hear of it. Is everything … otherwise all right?”

“No, it’s not. Nothing’s all right. This is about you.” He pointed at Gideon. “And me. They’ve done this to us,not just to those poor people they’ve killed out of hand.”

“They wish to discredit me,” Gideon said stiffly.

“Oh, that’s not all they want. No, no, no. I’m afraid not.” Grant walked to the far window. He held his hand against the glass to guard his eyes from the glare. Seeing nothing outside, he reached up to draw the heavy velvet curtains shut. He turned around. “They want to keep me cowed, as surely as they want to make you look like a murdering maniac. Maybe they want to make me look mad, too. I had to escape two Secret Service men in order to arrive here unseen. At least I believeI haven’t been seen…”

Lincoln said, “Dr. Wellers is confident they want him dead, too. It’s quite a party here tonight.”

Gideon explained, “Wellers and I were together when the murders happened.”

“Then he might have a point,” Grant said. To Lincoln, he added, “You need to guard this man’s life with … with yourlife. The four of us,” he said, so out of breath from his trip, and from the revelations that had brought him there, that his speech caught in his throat, “are all that keeps them from milking the Union nearly to death, and slaughtering thousands for the profit.”

Gideon put his gun back in his coat and clenched his fists. He measured his words against his fury and rising fear, and cast it all at the president. “God damn,but you’re being shortsighted, sir! If the war runs on, it won’t just be Atlanta that falls to the plague. Remember the Fiddlehead. Remember the numbers, and the predictions: the continentwill fall within the decade if we cannot stop this madness and force a conclusion. Possibly the world!”

Nelson Wellers laughed ruefully. “It’s not enough to save our own skins, or the entire nation.” He sighed. “No, we must save the world as well. All from this library.”

Lincoln gave a crooked shrug. “There are worse places from whence to mount a defense of civilization.”

Grant seemed to agree, but he was flustered, and he rambled. “They threatened me, Abe. Not just me, but Julia—they’ve threatened her. That terrible woman, that dragon in a hat. She’sthe one who did this.”

“Where is Julia now?” his old friend asked.

“Baltimore, but that’s not far enough away to keep her safe from Haymes.”

Gideon’s nails dug into his palm. He fought to keep from hitting something for emphasis, but managed to restrain himself for only a few seconds before taking a swing at a bookcase. He knocked it so hard that it rocked precariously, then settled.

“For God’s sake!” he shouted. “Have you not heard a thing? Baltimore won’t be far enough. New York won’t be far enough. Mexico won’t, and Argentina won’t. Canada won’t. The Department of Alaska won’t! There will be no place in this hemisphere far enough away to protect anyone from this walking plague!”

Nelson Wellers positioned his lean frame between Gideon and the other two men with his hands up. “You’re right. We know you’re right—we’ve already said as much. But in the short term, we must take what action we can.”

“We don’t have time for the short term!”

Wellers gave up, flung his upraised hands into the air, and finally hollered back. “ You’rethe one who wants to stop a damn news story before morning! You’re wanted for murder. That’s a short-term problem, now, isn’t it?”

“Oh, for Christ’s sake!”

“Gentlemen!” Lincoln tried to roar, but it came out as a cough. Grant went to his side, and Nelson looked back to make sure that it wasn’t any worse than that.

Gideon did not back down. He mimicked Wellers’s tone when he said, “They want you dead. That’s a short-term problem, too, now, isn’t it?”

“Short term for you—somewhat longer for me! But yes, fine. It serves my point,” Wellers said, struggling to calm himself. “I would prefer to survive. You would prefer to stay out of prison. The Union must be preserved. The war must end. The weapon must be stopped. The walking plague must be addressed. We need stepping stones, Gideon. Stepping stones.”

Gideon argued, “How are we supposed to stop it? We don’t even know where it’s headed.”

“Executive order!” cried Grant. “I do still wield someauthority, you know. I’m only the president, as I’ve been reminded more than once in the last week.”

“Then why not send an executive order now?” Wellers asked plaintively. “Recall the project, bring the weapon home.”

Grant fidgeted like an angry man, pacing with a stomp. “Because no one will admit that it exists. I can’t recall the project; I have to recall the mission itself. And I can’t find it.”

A disquieting pause fell, and then the doctor said, “Someone will. Someone has to. Maybe … maybe Troost’ll hear something.”

Lincoln finished his coughing fit, then rallied himself to speak. “We’ve heard nothing from him since yesterday morning, and no mention of Maynard.”

“If anyone can track it down, he can,” Wellers said with desperate confidence.

Gideon didn’t argue, but he worried all the same. Troost was one of a kind, but he already had one mission on deck: bringing the Bardsleys to safety on the northern side of the line. He could swing the impossible, yes, absolutely. But how many impossible things could he juggle at once?

Grimly, he warned, “We can count on Kirby Troost to do his job, and more. But right now, we need a plan. We need to get our story straight and our actions in order before Haymes makes her next move.” He straightened the bookcase he’d knocked ajar in his moment of anger, nudging it back into place and setting two books aright. “We need to send word to our operatives before the police find their way back here, as they inevitably shall.And when Troost finishes evacuating my family, he’ll be back. We must be certain that we are ready for him.”

Fifteen

On Monday morning, Maria awoke to a knock on her hotel room door. She threw her coat over her dressing gown and fished around on the cold wood floor for her slippers, but couldn’t find them, so she gave up and tiptoed from rug to rug, turning up the heat as she passed the radiator. “I’m coming,” she called sleepily. She wondered what time it was, but could see through the crack in the curtains that it must be an hour past dawn at least. She hadn’t meant to sleep so late.

Henry Epperson was staying right across the hall, so she assumed that it must be him, but when she opened the door, she found an errand boy of perhaps ten or eleven years old with a stack of telegrams in his fist. “Are you Miss Boyd?” he asked. She nodded. He thrust the loose papers forward. “Here.”

“Thank you,” she said, rubbing her eyes. Seeing that the boy lingered, she added, “One moment, dear.” Her bag was sitting next to the washbasin. She stuffed her fingers into the side pocket and pulled out some pennies. “Here you go.”

She closed the door behind him and sorted the messages by the time they’d been sent—which was trickier than it should’ve been, as they were entirely out of order. But once she’d corrected the situation, she knew she needed to rouse Henry immediately.

She located her slippers, which had been kicked beneath the bed. She pulled on a pair of socks before donning them, not caring how silly it looked and doubting that anyone would notice. Across the hall she went, where she rapped her fist heartily, repeatedly on Henry’s door. “Henry? Are you up yet?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said through the door, then opened it with a smile. “I’ve got some coffee in here. Can I talk you into sharing?”

“Coffee sounds wonderful.” She stepped past him as he held the door ajar. “But there’s no time to dillydally!”

He looked confused. “Not even for coffee?”

“An errand boy brought me these.” She showed him the notes. “They’ve been piling up overnight, apparently. One in particular is marked for urgent, immediate delivery, but it would seem that the taps aren’t manned as thoroughly as one might wish.”

Henry shook his head. “The military missives get first handling. Civilian messages get processed whenever the intake officer feels like sorting them out.”

“That’s a bum deal if you need to send a note in a hurry,” she complained.

“Far be it from me to argue with you. So what’s the rush?”

She fed him the telegrams one by one.

SUMMARY OF NURSING NOTES RECEIVED STOP AGREE ON ALL POINTS REGARDING GAS AND WEAPONS PROJECT DESIGNATED MAYNARD STOP WILL EXPECT REPORT ON ROBERTSON UPON YOUR RETURN FRIDAY STOP UNCLE A

MAYNARD IS ON THE MOVE STOP AUTHORIZATION GIVEN SANS UNCLE G STOP TARGETS CIVILIAN NOT MILITARY STOP ALERT OUR COUSIN KT TO WITHDRAW TO OTHER SIDE OF MD IMMEDIATELY STOP YOURS DR W ON AUTHORITY AND APPROVAL OF UNCLE A

“MD?” Henry frowned.

“Mason-Dixon, I should think,” she replied. “But Project Maynard … if Troost was right, now’s the time to reallyworry.”

Oh, I’m already worried plenty,” he said, and fiddled with the small slip of paper. “ Civilian targets.That’s not good.”

“It’s not a surprise, either. Everything I’ve heard of Haymes suggests she’s utterly soulless. But it doesn’t stop there. Look, here’s the next one.”

DO NOT RETURN TO DC STOP FIND OUR COUSIN KT FOR ASSISTANCE STOP MOST LIKELY TARGETS LARGE CITIES STOP MAYNARD COULD CLEAR A SQUARE MILE STOP RESULTING CLOUD MAY TRAVEL MILES FURTHER STOP WILL SEND WHATEVER HELP WE CAN MANAGE STOP

“I don’t even know who sent this one,” she said in a whisper. “Dr. Wellers, I expect, though it might be Dr. Bardsley.”

Henry didn’t dwell on that part. “Oh, God,” he said again.

“We need to find Kirby Troost, unless you think ‘KT’ stands for anybody else. But it’s his job to get Gideon’s family out of the South. I’m not sure how much assistance he can be to us until he does.”

He smiled weakly. “Only because you don’t know Kirby. He can handle more than one task at a time, and you can bet he’ll have some ideas and some connections. He always does. Come on—get yourself dressed, and I’ll get us a carriage. A clean carriage,” he emphasized, meaning one that wouldn’t need a driver.

“Five minutes, and I’ll meet you downstairs.”

In five minutes she dressed herself, threw on her boots, and lit a tiny fire in the enamel basin to destroy the telegrams. When they were reduced entirely to ashes, she grabbed her tapestry cloth bag and dashed down the stairs to find Henry standing beside a tiny cabriolet with a puttering, sputtering engine that shook the whole frame as it idled.

“After you, ma’am,” he said, holding the door open and offering his hand for her to climb up inside. She took it and ascended into the narrow cab, adjusting her skirts so he could shut the door. He crawled up into the other side, shut his own door, and adjusted the levers and wheel. He wrenched the vehicle into gear and it rambled forward, then he hit the brakes to avoid hitting a newspaper seller who’d dropped something in the road. “Sorry!” he shouted out the window. “Sorry,” he said again, and set the car moving forward, more carefully this time.

“It’s a shame there’s no glass in these windows, don’t you think?” Maria asked with a shudder. She tightened her coat and twisted her gloved hands up in her scarf, but that wasn’t enough to make her comfortable, not with the wind rushing inside the cab.

“Not such a shame if you’re keen to keep breathing. The exhaust creeps up from the engine—that’s why the windows are fixed this way. It’ll warm up a bit as we go, I promise. Heat also creeps inside, especially at your feet.”

They drove a few blocks east, which was not at all in the direction of Lookout Mountain—a fact that Maria knew because she could see its craggy, winter-bald point off to the south. She was on the verge of asking why they were taking this path when Henry explained, “We have to get past the wall, and the nearest gate is over here. Under different circumstances, I’d take the long way around to cover our tracks … but we’re short on time, and I don’t know about you, but I haven’t seen anyone following us.”

“No, we’ve been fortunate so far,” she said, with more confidence than she felt.

Before long, the wall loomed up close.

It was a sheer, flat, inscrutable thing—a vast construction designed with traditional military precision and lack of finer detail. A massive half-moon over a hundred feet high, it was painted Confederate gray, partly as a patriotic statement, partly to protect it from the elements, and partly because gray paint was cheap. A wide double gate hung open, with one lane of traffic spilling slowly inward, and one lane of traffic proceeding outward at a somewhat faster pace.

Maria reached into her bag for the papers identifying her as a nurse, but Henry told her not to bother. “They check you coming in, not going out.”

“They didn’t check mecoming in.”

“You came in on the train.”

“Ah.” That was true—and her papers on the far end had been carefully scrutinized, now that she was awake enough to remember the process.

Henry waved to the guard, who waved back in a casual, unconcerned manner. Then they were outside, in the poorer suburbs that had been chopped off from the urban military center. Off in one direction, Maria saw Missionary Ridge curving gently around the valley; and to the right, she could barely see the leaning tip of the mountain peeking over the wall. It all felt very medieval to her, like a castle surrounded by serfs.

Henry guided the car to an overgrown side road, where they could watch travelers come and go through the gate without being easily observed. Several minutes passed without anything suspicious happening, so he and Maria concluded that they hadn’t been followed, and were on their way with a somewhat greater sense of security.

Outside the wall, the roads were not made for horseless travel. They took it slowly because the engine was quieter in a lower gear, and because the brick-paved streets were rough on the hard-rubber wheels of the car, never mind its occupants. Horses came and went, sometimes ridden, and sometimes pulling loads; children dashed out into the slow-moving traffic, chasing dogs, toys, or one another. Potholes abounded, for bricks were sometimes pulled from the street and used to patch, repair, restore, and rebuild outhouses, sheds, and crumbling foundations. Intersections did not always meet at the correct angles, and no signs indicated which way traffic was expected to flow.

Big trees stood seasonally naked on corners and in yards, and their brittle branches reached high overhead, throwing scattered shadows around these outlying places. The houses were small and fiercely guarded, or else they were large and in uncertain repair. The people were overwhelmingly poor and not in the military—Maria did not spy a single uniform. And the closer they came to the mountain, the more colored families she saw.

“I feel … conspicuous,” she whispered as softly as she could, while still making herself heard above the engine.

“We areconspicuous. But we are relatively safe.”

“What if someone comes along behind us and asks if anyone has seen a carriage like ours?”

He shrugged. “The locals will say they’ve seen no such thing. No one who asks them questions has their best interests in mind. It’s safer for them to see nothing, and say nothing. But they won’t hand us over, because they know what we’re doing.”

“They can’t possibly. Webarely know what we’re doing.”

“They know we’re going to the Church. Pretty much any white people who come out this way … that’s where they’re headed. And most of the people who live out here keep themselves blind and quiet, because it’s the only way to help without putting themselves in danger.”

Up to the long, narrow mountain’s ridge they rode, rattling past the edge of the river’s bend and along a packed dirt road that led under the railroad overpass that took all the trains around Lookout. The arch was overgrown with the dead trees left behind by winter—long branches, stripped roots, and a dangling lattice of Japanese weed, gone brown from the dry and chill. Along the arch’s top a train crept slowly, its wheels churning, its cars hauling coal or timber from east to west, or farther down south.

Under the arch, a horse appeared, galloping quickly toward them. Its rider almost lost his hat as he rode beneath the train, but he held it fast—and he drew his horse up short when he reached their car. Its hooves scattered bits of brick and pebbles, which clanged against the car’s metal plating, and the animal shifted nervously from foot to foot.

“Henry, don’t tell me that’s you…?” the rider called. He firmly reined the horse up to Henry’s window, and leaned his head down low. “Well, I’ll be damned. My luck ain’t usually this good.”

Maria leaned over, cocking her head to the side a bit so she could look up at him. “Mr. Troost! Just the man we were coming to see.”

He spit a gob of tobacco to the side of the horse, away from the car. “I should damn well hope so. Can’t imagine why else you’d be out this way. Anyway, I’m glad to see you’ve saved me a trip downtown. We got problems.”

“We got telegrams,” Maria agreed.

“And I got another one just now,” he said. His eyes were hard, and his hands were tight on the reins of the unhappy horse. “Follow me back to the Church and I’ll give you what I know. And jack that thing a little faster. We haven’t got all day. Shit, we might not have all morning.”

He nudged the horse back the way he came, and kicked it into a gallop once more.

Henry urged the car through first gear and into second, which had Maria clinging to the door and wondering if she might be sick. The vehicle tumbled over the lumpy roads, shuddering like it might come apart at any moment, but it stayed intact as it trailed Kirby Troost’s horse through an overgrown neighborhood of small, cheaply built bungalows with rickety porches and crooked steps. They gave friendly chase down a narrow street, Maria praying at every moment that they wouldn’t meet anyone or anything coming the opposite direction.

They passed one church on the left, a tall, flat-faced wooden structure painted white, but apparently this wasn’t the Station. They kept going until they found a sturdy stone African Methodist Episcopal church a few blocks farther down and partway up a steep embankment that disappeared into the mountain itself. Kirby Troost disappeared behind this church, down two scuffed ruts that passed for an alley. Henry followed him as far as he dared, until the winter-dead foliage threatened to bog down the car and stop it for good.

He pushed his foot down on the brake and hopped out.

Maria waited for him to open her door, then took his hand as she descended into the grass.

Kirby tied his horse to a post beside the church steps and then joined them. “Y’all’d better come inside.”

Inside, everything was dark except for the colored light that trickled through the tinted glass windows. The place was wired for electricity and gas lamps, and she could see how old fixtures had been refitted for the newer technology. But nothing was turned on, and the place was cold. There was certainly a furnace, but no one had lit it. The church looked deserted. Maybe that was the intent.

They marched past straight-backed wooden pews in tidy rows with Bibles and the occasional dog-eared hymnal scattered here and there. Then they climbed straight down into the baptismal font. Maria felt strange about it, but she stood aside and smiled when a false bottom opened up and a secret staircase was revealed below.

“Ladies first,” Kirby Troost said.

Henry elbowed him in the ribs. “Don’t be an ass, Kirby. You have a light?”

“Right here.” He pulled an electric torch out of his coat and offered it to Henry.

But Maria snatched it out of his hand and pulled the switch to turn it on. “Ladies first,” she reminded them, then sidled past them down the stairs. At the bottom she found a landing and a door, and Kirby Troost was beside her, though she’d never heard him join her. Only a superhuman effort kept her from flinching as he reached past her face and pressed a button once, twice, and three times … then paused and hit it once more.

“That’s so nobody shoots when we walk inside,” he told her as he retrieved the light. “This time, we’ll have to set chivalry aside. They know me, and there’s a chance they mightknow you, so stand back.”

The door opened a crack. Around the corner peeked a colored woman about Maria’s age with a lantern in her hand and a wary look in her eye. “Mr. Troost,” she said levelly. “And you’re not alone.”

“No, ma’am, and the cat’s not in the tree, either.”

She nodded and withdrew, taking the lantern with her. Its glow illuminated the interior of a large, comfortable living area with three other people in it: an older woman and a boy of maybe eight or nine, both colored; and a white man with a gun who nodded at Troost and said, “Back so soon?”

“They were on their way to meet me, so I found them faster than expected,” he said. “Everyone, this is Mary and Hank. They’re here to help. Or, from another angle, they’re here so I can help them,but that’s how it goes. Mary, Hank, that’s Dr. Bardsley’s mum and nephew right there, Sally and Caleb.”

“You know my son?” Sally asked quickly.

“I met him once,” Maria said.

Henry added, “I know him; he’s a great man. He might end the war and save the world, and we’re trying to give him a hand.”

This satisfied her, enough to release her death grip on her grandson. “All right then. Mr. Troost, if you say they’re with you…”

“They are, so don’t fret—not even for a moment. I’m going to take these nice folks back to the quiet taps. We’ve got some talking to do.” He cast a sharp glance at the white man, who hadn’t been identified.

“Go on back,” he said. “I’ll stick it out up here and see if the ship shows up.”

“Good deal. Come on, you two, this way,” Troost said to Maria and Henry. He led them back through the underground apartment with its hard wood chairs and two low beds, and out a door at the back end. As he went, he explained, “We have a telegraph line here. Runs underground, like the railroad, and it works just fine, so long as nobody messes with it. Not a whole lot of people know its signal, so don’t go running off at the mouth. I probably don’t have to warn you about such things, but don’t take it personal. Caution is the grease that keeps this railroad running smooth.”

“I understand,” Maria said quietly, following him along a corridor and past a couple of doors.

“Maybe you do, and maybe you don’t. If anybody gets a whiff of what goes on out here, dozens of people will get shot before word even makes it to the city. This whole block is floating on high treason, and everyone who knows about it is a suspect.”

“I really dounderstand. Believe me, I was a spy for years.”

“For thisside, yes. You only know what the Grays will do to protect a body. You don’t know what they’ll do to destroy one. In here.” He opened a door and guided them through. “I don’t mean any disrespect, ma’am, but I’m thanking Christ Almighty that no one recognized you back there. Having you set foot in this place is sacrilege, so far as they would figure it.”

“I never—”

He cut her off. “You want to tell me what you really think? How you really feel about slavery? Save your breath. If you want to help, and you don’t want to make any trouble for these people, then you’ll keep your past and everything else to yourself.”

He stopped and faced her. Maria didn’t flinch, but she didn’t press forward, either, even though she had the extra height on him and—if she was honest with herself—a few pounds on him, to boot.

He said to her, a little more gently, “Your silence is the only thing that can prove you here. Hold your tongue, hide your name, and don’t tell a soul about where you came from, or what brought you—unless you tell ’em it’s the Pinks, because that’s what I said already. Anything more than that and you start a panic and put us all in danger. You got it?”

“I … I got it.”

“Now, here are the … facilities,” he said, picking a word for the rigged-up taps system that filled the bulk of the room. Wires ran to and fro, and tap receivers were set up across a table, some of them quivering with a signal freshly sent or received. No one monitored them at the moment, though the white man from the living area showed up shortly to poke his head in the door.

“Holler if anything starts signaling through if it’s longer than you want to read.”

“Will do,” Troost said, then returned his attention to his guests. “I can take the script, but I’m slower than heis.” He cocked a thumb toward the door. “And, anyway, right now I’ve got other things to attend to. Most recent word from D.C. says we’ve got worse problems than we knew. How much have you heard?”

Henry said, “Maynard is apparently on the move. Could kill hundreds of thousands before it’s finished. And it’s pointed at civilian targets, not military ones, except maybe Danville.”

“It’s not headed for Danville,” Troost said firmly. “Not enough of a population center. It would be more convenient to send it to a bigger city.”

“Atlanta?” Maria guessed. It was the biggest city of all, outside New York.

“That’s the word on the wires. At present, it ought to be someplace south of Dalton, but north of Marietta. That’s as close as anyone could pin it down. The taps are having trouble between here and there, but I don’t know if it’s a conspiracy, or just an inconvenience. You can rest assured I’ll keep trying to rouse the Rebs, though. They’ll sure as shit want to know about it, and might even be able to help. You never know.”

“Anything’s possible. And now Maynard is somewhere within…” Maria wracked her brain, trying to make an educated assessment. “Seventy or eighty miles of here? That’s no pinpoint, but it’s a narrower window than we had before.”

“When we’re finished up here and you’re on your way, I’ll drop Mr. Lincoln a line to keep him informed.” Some flicker of uncertainty crossed Troost’s face, but quickly passed.

But Maria saw it, and she asked, “What? Is something wrong?”

Troost laughed, short and harsh. “Other than the end of the world, you mean?” He pulled a map out of a drawer beneath the taps and spread it out beside them. “I can’t be sure, but I think something funny’s up in the District. I don’t trust the wires there, not tonight. There’s an interruption someplace, and I don’t like it.”

Henry stiffened, and he narrowed his eyes. “You think Mr. Lincoln’s in danger?”

“I think everyone’s in danger, more often than not. But yes, him in particular. And maybe the president, too.”

“You think it’ll go that far?” Maria asked.

“It’s gone farther than him already. But there’s nothing I can do about that right now. Not from here.” Finished with the subject for the time being, he jabbed his finger at the map to guide them, and said, “All right. From where we’re sitting now, the fastest way to Georgia is that road right outside, the little highway you came in on. But the more direct route is thisroad, which cuts through the south end of town and out past the ridge. The main road drops down that way, and it’s a straight shot to Atlanta, then on to Macon, and so forth.”