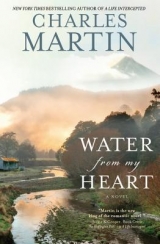

Текст книги "Water from My Heart"

Автор книги: Charles Martin

Жанры:

Современные любовные романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Chapter Thirteen

The rooster woke me, but it was the smell of coffee that got me out of bed. I walked out of the single-room shack occupied by the bed I’d been sleeping in. Two parallel walls of concrete block. Plastic sheeting on the other two. Rusted tin roof. An orange extension cord snaked out of the main house, across the yard, and under the door where it powered a light above my head and the oscillating floor fan. The door was made of horizontal slats with an inch or two of space between. It wouldn’t keep out much. Stepping back, I realized I’d been sleeping in a converted chicken coop.

I shuffled across the yard and onto the porch wearing another man’s shorts. From what I could tell, she’d already swept the dirt porch, washed and hung the laundry, fed the chickens, and cooked breakfast—which looked like beans, rice, and fried plantains. A pot filled with what looked like milk sat simmering on the stove. The smell of it wafted from steam off the pot and hung in the air. I waved and my voice cracked. “Hi.”

She was standing next to a large, waist-high concrete sink. The left side of the sink was a rippled section on which to wash clothes. The right side looked like a drain for clean dishes. The middle was a deep sink. She was hovering over the middle sink, pouring water from a bucket over her sudsy hair. When I first met her, her hair had been pulled up and back. Now it was wet and hanging nearly to her waist.

She rinsed again, then wrung out her hair and began brushing out any tangles. She pointed with the brush. “Breakfast there if you feel like eating.”

I pointed to the coffee. “May I?”

She nodded. Something about her body language told me she was in task mode and that I was one more task getting in the way of several others. She wasn’t unkind, but I could tell she was trying to figure out what to do with me.

I poured myself a cup from an old percolator, sat at the worn wooden table, and hung my nose over the mug. I was hungry enough to eat the table, but that coffee smelled so good. When I sipped, it did not disappoint.

She noticed my reaction. “Good?”

I nodded while the taste swirled around my mouth. The caffeine buzz was immediate and satisfying.

“You like good coffee?”

Another sip. “I’d let you put it in my IV.”

Over her shoulder, San Cristóbal sat smoking. She pointed to the smaller volcano, lush and green, that sat to the right. “Grown right there.”

The coffee was intoxicating. “The flavor is, well…wow.”

She nodded knowingly. “It ought to be.” She finished brushing her hair, then spun it into a tight bun at the back of her head. She poured herself a cup and sat. I extended my hand. “I think we’ve already done this, but I’m a little hazy. Charlie Finn.”

She nodded and bowed slightly. “Paulina Flores.” She waved her hand across the neighborhood. “Around here…Leena.”

“Thank you.” I waved my hand across myself. “For everything. I don’t remember much, but what I do remember tells me that it wasn’t pleasant.”

Her daughter appeared, sleep in her eyes, hair in her face. She walked up to me, extended both hands, pressed palms together—like she was swimming the breaststroke—and held them out, bowing slightly. She held the pose for several seconds. Waiting. Paulina said, “She’s honoring you.”

I cradled both her hands in mine. “Hello, beautiful.”

Paulina spoke softly over my shoulder. “Hola, linda.”

The girl listened to her mother, and a smile slowly spread across her face. I had a feeling she understood me, but she was waiting for her mother to give her permission to respond to a stranger.

“What’s your name?”

Her mother prompted her. “It’s all right.”

Her voice echoed inside me, taking me back to the sidewalk outside the cathedral. “Isabella.”

“Good morning, Isabella. Thank you for allowing me into your home.”

She puffed up as though she had information I did not. “You’re not in my home. You’re in the chicken coop. Momma put you in the chicken coop so the neighbors don’t start talking.” Her index finger started waving like a windshield wiper. “It’s not—” She put her hands on her hips, letting me know that she was about to unleash a grown-up word on me. Her lips moved slowly around the letters as she made the word. “Appropriate for you to sleep in our house.”

Look up the word “precocious,” and you’ll find her picture. I asked Paulina, “How is it that her English is so good if she’s grown up here?”

“Life is tough here. It’s a good bit tougher if you don’t speak English. I knew she’d get Spanish by default, so since she was born, I’ve spoken English with her.”

Isabella smiled wider, grabbed a red plastic mug, dipped it gently into the milk, and climbed up into her mother’s lap where she sipped on the milk, painting her upper lip in a mustache while her mother brushed her hair. Leena spoke over Isabella’s head and eyed the pot of milk. “Help yourself. We own one cow. Half Brahma. Half India. The Brahma half is strong and can survive the conditions around here, namely the heat and drought, but generally gives little milk. The India half is weaker but gives good milk. More robusto. Put them together in one cow and…” A shrug. “We drink milk on a regular basis.”

I hefted my coffee mug and smiled. “Why’d you help me?”

“Couldn’t very well leave you.” An honest shrug. “You’d either be dead or about to be.”

The little girl spoke up. “You looked drunk. Were you drinking?”

I laughed. She smiled again, leaned against her mother, and tucked her knees up into her chest. Her hair matched her mother’s, as did her eyes. Jet-black. I chuckled. “No.”

She didn’t skip a beat. “Do you drink?”

I shook my head. “No.”

“Are you telling the truth?”

“Yes.”

“Why not?”

“Never really started.”

“Then you’re a good man?”

So much wrapped in so small a question. I’d lied for so long. The memory of my parting with Shelly on the beach was still raw. I had no desire to suffer another self-inflicted wound in such a short amount of time. I shook my head. “No. I’m not.”

Paulina broke the awkward silence. “We didn’t know where to take you in León so we brought you here.”

“Where is here?”

“Valle Cruces. Forty-five minutes west.”

“I know I owe you some money. Everything’s in my hotel room in León.”

“No hurry.”

“Any idea how I might get back there?”

“Bus leaves in a few hours. Cost you a couple of dollars.”

I patted the pockets of my shorts. “Not a penny to my name.”

“Truck leaves in two days. You could hitch a ride then.”

“Truck?”

“Belongs to my uncle. He’s working today and tomorrow, but he can drop you in León day after tomorrow.”

“Any other option?”

She pointed to the road. “You can walk. Although thirty miles in flip-flops might leave your feet in worse condition than when you started.” I eyed my feet. She continued. “You can hitchhike, but unattended gringos with an ‘I’m lost’ look pasted on their faces have a way of disappearing around here.”

She could see my wheels spinning, but she said nothing. My options were few. “Mind if I stay until the truck leaves?”

She shook her head once. “We’ll be gone most of the day, so you’ll be on your own.”

I eyed her cell phone. “Mind if I call my hotel?”

She slid it across the table and helped me contact the young man at the desk. He answered and was glad to hear from me. I told him to hold my room and I’d pay him when I returned day after tomorrow. He agreed, said it was “no problem” and that my bike was still parked out back. It would keep.

I returned to Paulina. “I feel a bit guilty sitting here doing nothing when it looks like you’ve been working since you got up. Can I help?”

She pursed her lips and the space between her eyes narrowed as she considered this. She looked at Isabella, who was smiling and nodding. “You think he should go with us?” Armed with the ability to determine the course of the day, Isabella raised an eyebrow and considered me. Finally, having given it enough time, she nodded. Paulina pressed her nose to Isabella’s. “He could carry the backpack.”

Isabella laughed an easy laugh.

Paulina looked at me. “If you feel up to it.”

“Seems the least I can do.”

“It’s a long day, and in all fairness to you, it’s a lot of work for a guy who’s been as sick as you. If you go, you need to let me know how you’re feeling. Okay?”

“Deal.”

She filled a gallon jug with water, poured a few drops of bleach into it, and set it in front of me. She walked to a plant, twisted off a few stems, and shoved them into the water. “You need to drink most of this before we go. I doubt you’ll get your strength back for several days, but this will help. You took four bags of IV fluid, but I doubt that was enough.” When I lifted it to my lips, the water smelled of mint. “We’ll leave soon as you’re ready.”

* * *

The sun was rising and I was already sweating. I drank the entire jug, which seemed to make her happy and did not make me need to pee, which told me that I really needed it. We refilled it, and she began shoving medical supplies and food into two large backpacks plus a third, which was much smaller. She handed me a worn-out baseball cap and said, “You’ll want this in a few hours. The midday sun around here will bore a hole in your head if you let it.” She also handed me an old pair of tennis shoes. They were too small, but the ends had busted open, allowing my toes to stick out the front. “Where we’re going, those will be better than flip-flops.”

I shouldered the backpack, which felt heavy, and we began walking. Isabella hopped along in front of us. Her backpack was loaded with a bottle of water and a bag of candy. Both Paulina’s bag and mine had been loaded with medical supplies, medicines, rice, beans, and oil. My bag might have weighed ninety pounds. Eyeing the mountain in the distance, I shifted under the weight of the straps, knowing that in about two hours ninety pounds was going to feel like two hundred.

Paulina put her hand on the pack. “Is it too much? We can leave some here.”

I ran my thumbs below the straps that were knifing into my shoulders. “No, I’m good.”

“You sure?”

“No worries.” In truth, it was pile-driving me into the earth, but this lady had just nursed me back from the dead. What else was I going to say?

She smiled and walked on ahead of me, her skirt waving in the hot breeze.

Walking out of the yard, Isabella routed us past the corner of the chicken coop. She leaned over and stared into a small area protected by chicken wire. Inside sat a duck, staring quietly up at us. Isabella poked it with her finger, prompting the comfortable duck to exit her perch and waddle a few steps away, revealing the four eggs beneath. Satisfied, Isabella shouldered her pack and continued walking. I had never seen anyone raise ducks, so I asked, “You guys raising ducks?”

Leena spoke over her shoulder. “No. They’re chicken eggs. We’re just using the duck to hatch them.”

That prompted the next obvious question. “Isn’t that confusing to the chicken?”

She laughed at me. “The duck doesn’t know the difference.”

“Whose duck?”

She pointed to a house on her left without looking. “Neighbor’s. It’s on loan.”

I wasn’t prepared to argue this. “What happened to the chicken?”

A shrug. “Don’t know. Woke up, found four eggs in the nest and a bunch of feathers out here in the yard. Haven’t seen the chicken since.”

“What will you do with the chickens?”

“Hopefully produce more eggs. Isabella likes them scrambled.”

The simplicity and matter-of-factness of life around here was striking.

* * *

The road wound along a riverbed. A man, woman, and two kids passed us riding a motorcycle, as did several pickup trucks overloaded with people. Most of the trucks were Toyotas. Older versions of the one Zaul took from his father. The cabs were loaded with six or eight people, and the beds were filled with fifteen to twenty each. Most were headed up the mountain. A few were headed down. Young barefoot boys, wearing tattered straw hats and riding horses, whistled and herded their cows along the road, most of which was lined with thick rows of sugarcane almost fifteen feet tall. As we walked, crosses—the size of a man—rose up out of the earth and dotted the woods on either side of us. There seemed to be no pattern. But we couldn’t walk fifty yards without seeing another cross. Some were next to the road. A few were nailed to trees. Many had been stuck in the mud of the riverbed and surrounded by rocks. Most were in clumps. Three or four together. In one spot, I counted nineteen. Singles spread out like bread crumbs. I pointed and the tone of my voice asked the question. “Valle Cruces?”

She nodded and felt no need to explain. A few steps later, she turned to me. “Charlie?”

“Yes.”

She waved her hand across the road and kept walking. “You might want to use another name.”

“Why’s that?”

“It’s English for Carlos, and that name isn’t real popular around here.”

A young boy, maybe five, wearing only underwear, ran barefoot up to Paulina. His face and hair were filthy. As was his entire body. His nose was running and the snot trickled down his lip. His right ear was crusted with yellow dried wax and a dark ooze. He held out his hands to Paulina. “Buenos días.”

He responded with a muffled “buenos días.”

She reached in her bag and handed him a banana, which he gladly took. Then he turned to me, held out both hands, and bowed like Isabella had. I took both his in mine and said, “Good morning.”

Feeling released, he turned and took off running back toward a plastic-wrapped structure beyond the trees. A man in a hammock waved at Paulina as we passed. She returned the wave. She spoke to me while looking at the man. “Don’t touch your mouth with your hands until you’ve washed them.” Her eyes followed the boy. “People around here don’t have toilet paper.”

I tried to make conversation. “How often do you make this trek?”

“Every Wednesday. Sometimes on the weekends.”

“How long is it?”

“Six miles.”

“Up and back?”

She shook her head once. “One way.”

I considered this. “Why all the crosses?”

She spoke without looking at me. “Something happened. Years ago.” She lifted her head and spoke while surveying the landscape. Her voice betrayed a sadness. “And it is happening still.”

We walked in the quiet—the river slipping silently on one side, and on the other, sugarcane groves that exploded in tight clumps like giant porcupine quills. Soon the landscape shifted, turned uphill slightly, and the trees returned. Tall trees, some nearly eighty or ninety feet tall, grew up and covered the road. Other trees, mostly fruit, filled in the shady space beneath. On a slight incline and bend in the road, Leena reached up, grabbed the low-hanging fruit with one hand and with the other she unsheathed a machete from her pack. The machete had been sharpened many times, and the rounded blade had been replaced with a long stiletto. She placed the fruit on a rock. Isabella waited patiently. Paulina reached in her pack and then squirted hand sanitizer into my hands. Isabella held out her hands, and she did likewise. Then Paulina cut the fruit, which was about the size of a football. The inside was a deep purple and orange and looked like a distant cousin to a cantaloupe. She sliced the fruit, then stabbed it, and, careful not to touch it with her hands, she gave it first to Isabella and then to me by holding out the flattened machete blade, which acted as a skewer.

She noticed me eyeing the blade and smiled. “I washed it. And hold it by the rind. Never touch what you eat with your hands no matter how clean you think they are.”

I slid the fruit off the blade. “Good call.”

The fruit was sweet, and we ate it as we walked, pitching the rinds in the woods alongside us. Behind us, a kid on a squeaky bike approached. He spoke to both of them in Spanish, tipped his hat to me, and gently rolled past. As he did, I noticed that he’d replaced the entire front axle of his bike with a short piece of rebar held in place by two pieces of thick shoe leather.

Finished with the melon, Leena walked to the side of the road, and with a swiftness and strength I’d not previously noticed, she cut a piece of sugarcane at the bottom, trimming off the leaves as we walked. Once trimmed, she peeled off the outer protective skin and held it out to me. “Just pinch the end with your fingers.” I did as instructed, and she brought the machete down quickly, leaving me with a ten-inch section of cane. As I stared at it, she said, “You suck on it.” She did the same for Isabella and herself, cutting several pieces for all of us as we walked uphill.

It tasted like candy, and I sucked it dry.

To our left, in an open field, two boys watched over a small herd of cattle, letting them graze. The boys were playing catch with two worn-out gloves that had long ago lost the stitching. As I looked closer, they were using a large lemon for a ball.

Finally, the road turned up steeply, and Isabella returned to her mother and handed her pack to her. I offered to carry it and she gladly agreed. It was a pink Dora the Explorer backpack. The water bottle was empty and the bag of candy had been opened. We climbed up through the trees and eventually into the coffee groves Paulina had pointed to this morning. “Paulina, is this the coffee—”

“Leena. And yes, this is the coffee you were drinking this morning.”

“What makes it so good?”

A smirk, but she did not answer.

By this time, we were several hours into our hike and several miles up the mountain. She stopped, breathing heavy, and turned. She pointed northeast to the smoking volcano a few miles in the distance. Between us and the active volcano sat a dormant volcano. Its sides were lush green and the crater atop was well-defined except for what can only be described as a scar coming down one side. The scar traced the lines of the mountain, rolling along the shoulders, winding like a serpent just below us, where it then descended into the valley. I remembered staring out Marshall’s plane and seeing the scar leading to the ocean. The pieces began to fall in place. “A decade ago, Huracán Carlos hovered over Nicaragua for several days. During that time, it dumped twelve feet of rain.” She turned in a slow circle. “Here.” Her eyes lifted toward the Las Casitas crater. “There was once a beautiful lake up there. The rain filled it to overflowing. The weight cracked the mantle, caused a miniature eruption, blew out the side of the mountain, and created a mudslide that ran—” Her finger began tracing the lines of the scar. “Down here. A mile wide and over thirty feet high, satellite imagery downloaded days later showed that it was traveling in excess of a hundred miles an hour.” She turned and pointed behind us where the world had opened. We could see for miles. She pointed. “All the way to the coast. Some thirty miles away.” She paused. “Coast Guard vessels would later pick up survivors floating on debris some sixty miles out in the Pacific.”

“And the crosses?”

“Over three thousand died that day. The crosses represent places where we found either bodies or parts or a piece of clothing or…” She trailed off. She turned and began slowly stepping forward, saying no more, and letting the story hang in the distance between us.

“Your family?”

She spoke without looking. “Twenty-seven members of my family.” Smoke from cooking fires hung in the trees above us. She waved me on. “Come on. We’re late.”

We climbed quickly through coffee plants as tall as me. Leena ran her fingers through the leaves, plucking a few beans. She spoke over her shoulder. “They started picking them last week.” Isabella ran ahead. Laughing in the bushes ahead of us. Leena climbed effortlessly up the steep incline. I had not regained my strength, and it was showing. I doubted I could run a six-minute mile right now. I lagged behind, slowly plodding forward. With each step, my pack felt like it was driving me deeper into the ground. She stared down at me. “What’d you say you did?”

“I didn’t, but—” An awkward chuckle. “In a previous life, I worked for a man up north. Boston. He ran a private investment firm. Which meant he—”

She spoke without looking at me. The tone of her voice told me the smile had not left her face. “I know what it means. I’m poor. Not ignorant.”

“Sorry. My bad. I didn’t mean to—”

This time she turned to look at me. “Judge a book by its cover?”

Leena was easy to talk to, and while what she said was true, she didn’t speak it in such a way that it pierced me. She wasn’t trying to one-up me. “That bad, huh?”

She raised both eyebrows and then extended her hand, offering to help pull me up a steep step. I took it. “Anyway, he had a lot of money. I was something of an errand boy. He was always hiring and firing—”

She interrupted me. “That include you?”

An honest shrug. “Eventually, yes. Pretty much. Anyway, when he would interview guys who had either been fired from their previous job or somehow found themselves between jobs, they would all use the same buzzword. Each would sit in that interview, cross his legs, and hope he couldn’t see through their polished veneer as they said, ‘I’m in transition.’ I can’t tell you how many times I heard that spoken across the table with such rehearsed polish.” I nodded as I tried to catch my breath. “But climbing up this Mount Everest with five hundred pounds on my back, I now understand what they meant because that feels about right. I’m in transition.”

She laughed and pressed on, winding through the trees.

We turned a corner on the road and were met by an old wooden sign overgrown with vines. The sign was five or six feet wide and just as tall. The paint had faded, chipped, and a few of the boards had fallen off, suggesting it had not been maintained in a long time. The name on the sign read, CINCO PADRES CAFÉ COMPAÑíA. Below that, an older sign, with hand-carved letters, read: MANGO CAFÉ.

I stumbled and caught myself. Leena turned. “You okay?”

I stared at the sign, the color draining from my face. “Yeah.”

She returned and placed her index finger on my wrist, quietly counting. After fifteen or twenty seconds, she let go but her suspicion had returned. “You sure?”

I waved her off. “Yeah. The truth would take too long.”

“Let me know if you’re feeling faint.”

I was feeling a bit more than faint, but I decided not to let her know that.

Moments later, we cleared the trees and walked out onto what would become the plateau on the shoulders of Las Casitas. Before me stood two tin-roofed, barnlike wooden structures. Two stories and thirty doors on a side. Leena spoke as we walked. “Families work the coffee. They make a dollar and a half a day. The skilled workers, the sifters, make two dollars.” She pointed at the buildings. “They live in these rooms. Sometimes as many as six to eight people will live in a six-by-six space. No ventilation. No heat. No cooling. They have no school here, no medical care, and most will never leave this mountain. But it’s better than the alternative.”

“I’d hate to see the alternative.”

She echoed my words. “You’ve been sucking on it the last hour or so.”

“Sugarcane?”

“The curse of Nicaragua.”

“How?”

She waved me off. “The truth would take too long.” She pointed to the work ahead of us. “We collect medical supplies and food from churches from Valle Cruces to León and then bring them here. It’s not much so we stretch it.”

“Is that why you were in León?”

“Yep.” She pointed at a small table beneath a gigantic tree off to our left. “We’ll be here for an hour or so. Let the healthy come to us. Once they thin out, we’ll go to them.”

By the time we took off our backpacks, a quiet and well-mannered line of about sixty people trailed off around the tree and toward the closest building. Most of the adults were looking at me. Paulina picked up on it. “Most have never been this close to a gringo.”

The first woman had a gash in her hand. Dirty. Paulina spoke to her while she washed the woman’s hands in warm water. As she spoke to the woman in Spanish, she translated for me. “I’m telling her that she needs to wash it in warm water several times a day. She doesn’t really understand germs so it’s an uphill battle.” While she worked, a group of twenty or so kids circled me with quiet fascination. Leena said, “You’re probably the first white man some of these kids have ever seen.”

Most of their noses were snotty. The mucus ran in streaks down their faces. “What’s with the runny noses? Seems like everybody around here needs an antihistamine.”

She laughed at my ignorance. “They live in homes where everything is cooked over woodstoves. They don’t ventilate them because the smoke keeps out the mosquitoes, so most kids around here grow up with an excess of smoke inhalation. Most of their lungs are inflamed, and about half are asthmatics. We’re working with them to ventilate the smoke, but they say ventilating a house lets in the ghosts on this mountain.” She pointed to the kids milling around me. “You can’t tell, but they’re actually a good bit healthier now than they have been in recent years.”

“How so?”

“Their stomachs. They’re not swollen.”

“What’d you do?”

She pointed to our water jug. “Added bleach to their water.” She eyed the mothers. “Educate the mothers and the entire plantation changes. A few years ago, I started bringing bleach and slowly adding it to their water. They didn’t like it, but then the worms stopped showing up when they changed diapers and the kids’ stomachs returned to normal. Now, they listen to me and add bleach to everything.”

A pregnant girl—maybe fifteen—walked up and spoke quietly to Paulina. Paulina listened, holding both her hands, and spoke in hushed tones. She gave her a bottle of children’s aspirin and the young mother walked off. An old man stepped up and began pointing at his hip. Leena again listened, her eyes staring intently into his. Isabella sat just to her left, giving each patient a piece of candy. The kids were milling around her, taunting her for candy, but she paid them no attention whatsoever.

“Where do they get their water?”

She pointed to a creek that ran through the property. “Who really owns this place is a bit of a mystery to all of us. We do know the planting rights are leased, but to whom is anybody’s guess. Whoever it is employs a foreman to run interference. Over this hill, whoever it is pastures his cattle—and his pigs. Every horrible thing known to man floats down that creek and right through here. Including some really nasty parasites. The families who live up here have to walk several miles down to get clean water, and then they’ve got to climb back up here, and when they get done working, most don’t have the energy to do that so they drink what’s at hand.”

“What about a well?”

She pointed to our left. “Just over that rise. Took two men more than a year because they had to dig it so deep. Used four lengths of rope making it over three hundred feet deep, which is a long way for a hand-dug well.”

“Was the water any good?”

“Some say God himself drank from that well.”

“What happened to it?”

“Charlie’s mudslide.”

“Why don’t they just dig it out? Seems like the hard part’s already been done.”

“Awful dark for the man at the bottom of that well, and nobody wants to be the man at the end of the rope. Besides, people here think the devil will own their soul if they dig out a well that God filled in.”

“You don’t believe that, do you?”

“I believe there’s a connection between that well and this mountain.”

I scanned the squalor walking around me. “But wouldn’t it help these people to have clean water?”

She answered without looking. “Yep.”

I spoke as much to myself as her. “That doesn’t really make much sense.”

A chuckle. “Welcome to Nicaragua.”

The third patient was a woman who might have been in her fifties. She was skinny, had lost about half of her teeth, and she had been beautiful before the sun weathered her. Her hair was turning gray, and whenever she smiled, her lips hooked on two of her remaining teeth. Paulina hugged her when she saw her. The woman spoke quietly but quickly. Leena listened and then reached for me. She said, “Charlie, I’d like you meet my good friend Anna. She’s lived here twenty-seven years.” I held out my hand and she shook mine. Her hand was frail, calloused, and tender. Leena handed me a pair of needle-nose pliers and ushered Anna toward me. “She’s got a tooth that’s giving her some trouble. I’m going to run in here and check this little pregnant girl to see how far along she is, and Anna needs you to pull her tooth.”

With that she turned and began walking off. “What!”

She laughed over her shoulder. “Don’t worry, she’ll show you which one hurts.” She held up a finger. “And don’t pull the wrong one. She doesn’t have too many left.”

Leena disappeared through one of the worn wooden doors, and Anna stared up at me with beautiful blue eyes and hands crossed. I held up the pliers and asked, “Which one?”

She wrapped her hand around my hand, which held the pliers, and gently pointed to a top rear molar. Then she opened wide and stood waiting. Isabella stared up at me, sucking on a piece of candy. Paulina had disappeared, and a line of hopeful, tired, and sick people waited on me to pull Anna’s tooth so that I could get to them. I opened her mouth wider with my left hand and gently placed the pliers on the tooth in question. “Is that the right one?”

She made no response.

I asked again. “Sí?”

She nodded.

So I gripped what remained of the abscessed tooth and tightened the pliers as best I could. The smell coming from her mouth could have gagged a maggot. I held my breath and tried not to. Careful not to hurt her, I pulled gently. Thankfully, the pliers gripped, and the rotten and infected tooth slid from its hole in her jaw. As the blood and pus drained, she took the tooth from the jaws of the pliers and slid it into her pocket. Smiling, she spat, patted my shoulder, and walked off. Over the next hour, I pulled nine teeth while Isabella watched in muted curiosity.

As the line dwindled, a small boy came to me limping. His big toe was red, infected, and there was a hole in it about the size of a pencil lead. I asked him to sit and poked around a bit. He tried to act tough, but I could tell it hurt him. Leena encouraged him to let me look at it. He stiffened and gritted his teeth. I felt like there was something stuck up in his toe, but I couldn’t get at it without hurting him. Seeing the muscles of his jaw flex, I squeezed his toe like I was popping a zit. At first, nothing. I stopped to get a better grip, and he took a deep breath and held it. I knew it was hurting him, so something had to be stuck in there. Finally, I pressed with both thumbs, and he let out a small cry. When I did, pus oozed and the tip of something stuck through his skin. His eyes were teary, but I showed it to him and asked Leena to ask him if I could keep going. He nodded and pointed at his toe, then poked me in the arm and nodded some more. I took that as a good sign and squeezed one more time. This time, white-and-green stuff shot out followed by a thorn. I took Leena’s tweezers and slowly pulled it from his toe. His eyes grew wide as I held the thorn—nearly three-quarters of an inch long—in front of him. He smiled wide. We bathed his foot, massaged as much antibiotic ointment into the hole as we could, and then wrapped it in a bandage with strict instructions from Leena not to walk barefoot for at least a week. He nodded and carried the thorn in the palm of his hand to show his mom. When he walked off, his chest had puffed out a bit. He looked up at me. “Gracias, Doctor.”