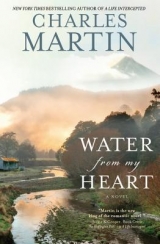

Текст книги "Water from My Heart"

Автор книги: Charles Martin

Жанры:

Современные любовные романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Chapter Seventeen

The three of them were dressed and ready when I walked out at six. We exited the hotel front doors and walked a few blocks down the street until we caught the smell of fresh baked bread. When it grew stronger, we turned left, and by the time we reached the door, my salivary glands were pumping double. We walked in, were greeted by a fair-skinned, blond-haired woman who looked Swedish and was sliding steaming trays into a glass counter display. Paulo and Isabella sat while Paulina ordered for each of us. Within a few minutes, one of the kids behind the counter delivered three delicious cups of coffee along with an entire tray of croissants and Danishes.

I ate six.

Isabella and I laughed as the chocolate crusted the corners of our mouths. Starting on my seventh, I stared at the croissant and said, “I think they just dip the whole thing in butter.”

While we were eating, the busboy began clearing the tables around us. A good-looking kid, clean-cut, apron, hard worker, looked like he’d lifted a few weights. But that wasn’t the feature that caught my attention. I asked Paulina to call the owner to our table. She did and the Swedish lady appeared. “Everything okay?”

I pointed at the kid. “How well do you know him?”

“Mauricio?”

“If that’s his name.”

“He’s my nephew. Worked here two years. One of the more reliable kids I have.”

“You ever caught him lying to you?”

She raised an eyebrow. “No.”

“How about stealing?”

Her face tightened. “Why?”

“You mind bringing him over here?”

“Sir, I’d prefer you speak to me first—”

“Just call him over, please.”

“If you have a complaint—”

“Please.”

She did and he appeared at our table wiping his hands on his apron. “Sí, señor?”

I pointed at his watch. “Nice watch.” I said it that way because I wanted to catch him off guard and gauge his reaction.

He smiled and nodded proudly, holding it out for me to see. If there was guilt, he was a better actor than most Academy Award winners. The owner watched without comment, but she looked ready to pounce. I asked, “You get it locally?”

“Sí, señor. I buy from”—he pointed at the floor—“here. Man who eat here say he no need and sell me less money.”

Everyone’s attention at the table was glued to his wrist. “You like it?”

He nodded, but then frowned and began to wonder. “Señor?”

“On the back, beneath the band, some words are written. You know what it says?”

He looked at the owner, then back at me. He shook his head. “Señor?”

The owner broke in. “He says he bought it, sir. If you think—”

I wrote on a napkin, folded it, and set it on the table in front of them. “Five days ago, I was mugged, stripped, and everything I had taken as I lay sick in the street.” I looked at the kid. “Now, I doubt you had anything to do with that, but whoever you bought it from may have well taken it off me, and unlike everything else, it can’t be replaced. I’d like it back.”

He frowned. The owner said, “Take it off, Mauricio. Let’s see.”

He unbuckled it from his wrist, pulled the band away from the back, and read the words. I opened the napkin and spread it across the table. He read it out loud. “Never again.”

I pointed to the grooves of the inscription. They were stained and dark, as was the back of the watchband. “That’s blood. It belongs to someone I love.”

He turned the watch in his hand, touching it lightly, as if it were delicate.

The owner’s look of suspicion transferred from me to Mauricio. I said, “Mauricio, I want to ask you a question.”

He straightened and nodded. “Sí, señor.”

“Did you take that watch off my arm?”

He tried to put the words together, but I apparently spoke them too fast so Paulina quietly translated. He shook his head. “No, señor. I buy it right here.” Another point.

Fortunately for Mauricio, I believed him. The owner waited quietly, wanting to see how this was going to pan out. I said, “How much you pay for it?”

He looked at the owner and then back at me. When he said nothing, I asked again. “How much?”

After a sideways glance at the owner, he looked over his shoulder and lowered his voice. “Catorce dólares.”

The owner looked at him with surprise. “Mauricio?” Her tone turned motherly. “You know how many days it takes you to earn that!”

I said, “Will you sell it to me?”

He extended the watch to me, shaking his head. “Señor, if it belong to you—”

I handed him twenty dollars. “Will you sell it to me for that?”

He nodded quickly. “Sí. Sí. Muy bueno.”

I turned to the owner. “That okay with you?”

She smiled, exhaled, and put her hand on the back of my chair. “Would you like some more coffee? I think Mauricio can brew you up something hot. He makes a pretty mean latte.”

I handed him the money, which he folded and stuck in his pocket. After shaking my hand, he returned to the coffee machine. The owner spoke to all of us. “Please let me know if there’s anything else you need.”

Paulo stared at me over his coffee mug. Isabella sank her teeth into another Danish, and Paulina watched me with a suppressed look of curiosity. I strapped the watch on my wrist and was finishing my croissant when a wrinkle appeared between her eyes. A slight shake of her head accompanied by the beginning of an amused smile. “You’re an interesting one.”

“How so?”

“You could have easily taken that watch from that kid.”

“I could.”

“Why didn’t you?”

“I have, or had, a friend in Bimini named Hack. He’s dead now. Used to tell me that people spend money on three things: what they love, what they worship, and what helps ease their pain.”

“Which of those does that watch represent?”

I ran my thumb along the bezel of the watch. “The third.”

“What else do you spend money on?”

“Good coffee, bottled water with bubbles—and Costa Del Mars.”

She pointed to the glasses resting on the top of my head. “Like those?”

A nod. “I have about sixty pair at my house in Bimini.”

“Sixty? As in six-zero?”

“My partner, Colin, is married to a lady named Marguerite who has a bit of a shoe fetish. Something like two hundred pairs. Had a cedar closet built just for her shoes. We often compare notes about our latest purchases. I guess we’re cut from the same cloth.”

She eyed the kid making my latte. “I think you made a friend.”

“That’s good ’cause I don’t have too many of those.”

* * *

Paulina and Paulo shared a cell phone with prepaid minutes, which they used only in emergencies. Paulina explained that they seldom, if ever, used it. Regardless, Paulo had been on it all morning. One call leading to another. He was talking on it as we left the café, and Isabella began steering me through the streets. Walking by the cathedral, she turned to Paulina, tugging on her arm. “Mami, can we go see Dadi?”

“Just a few minutes. We can’t stay long.”

Isabella jumped and climbed the same steps the naked dancer had pirouetted up a week earlier. Paulina noticed the strange look on my face but said nothing. We followed Isabella inside where it was quiet. And empty. Paulo dipped his finger in some water on the wall and genuflected. Paulina did likewise, although she added a bow, or curtsy, when she crossed in front of the center aisle. Isabella ran down the aisle and turned right, near the altar. Just above her, a lectern had been built on the side of a huge column that supported the ceiling. Stairs led up to a platform where the priest gave the sermon.

Isabella ran to the stairs, and when she reached them, she slid on her knees on the marble. Coming to a stop, she crawled on her belly beneath the stairs. When I reached her, she was propped up on her elbows speaking to a stone plaque. It simply read: GABRIEL.

Paulina pointed. “My husband is buried here.”

I nodded and said nothing.

Paulo sat behind us in the second row. Hands folded.

I sat on the stairs and could understand nothing, as Isabella was talking a hundred miles an hour in Spanish. Paulina sat opposite me on a pew and listened. “She’s telling him what’s happened since we were here last week. About finding you; you sleeping in the chicken coop, which she thinks is funny; about pulling teeth; and”—she smiled—“about last night.” Isabella said more but Paulina didn’t translate it.

We sat quietly, listening while Isabella rattled on—talking to the stone just inches from her face. I pointed behind me to the vault where her husband lay. “When?”

“Ten years ago. I was pregnant.” A single shake. “She has no memory of him.”

I rested my elbows on my knees. “How?”

“He was a doctor. Made house calls. We worked”—she waved her hand in front of us—“out in the villages. He contracted a virus that attacked the lining of his heart. Grew weak. We took him to a specialist, but he had self-diagnosed and knew there was no cure. Six months later, he died at home.” She looked around the church and waved at a priest. “He took care of all the priests. Many of the parishioners. He started a clinic”—she pointed to the back of the cathedral—“which continues to this day. About ten well-trained doctors volunteer their time here—a day here every two weeks. Some more than others. Because no one wants to anger the Catholic Church, hospitals donate medicine—and a lot of it. Some of which they give me when they can spare it. It’s where I get most of the medicine I need for my work. Barring a trauma, it may well be the best clinic in Nicaragua, and in some ways, it’s better than most hospitals in Central America. The church honored us by burying him here because he was beloved of the people.” She pointed to Isabella, who was whispering, her lips brushing the stone. “Still is.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Me, too.” She waved her hand across the walls around us, which were full of dead people who had been entombed in the walls and beneath the floor. “They paid over a million córdobas to be buried here. It’s a very great honor.” Her eyes fell on Isabella. Who was still talking. “She talks nonstop whenever she walks in here.” A pause with half a smile. When she spoke, she wasn’t looking at me. She was looking through the stone. “Every girl should have a daddy.”

* * *

Paulo clicked the phone shut and slid it in his front pocket, waving us onward. “Vamos.” He pointed. “Vamos al océano.”

I turned to Paulina, who was listening to Paulo. When he finished speaking, she turned to me. “Your friend has been seen around the ocean not far from here.”

“Really? Just like that?”

She held up a finger. “He’s been seen.” She stood. “Not found. Evidently, he likes to leave an impression wherever he goes.”

* * *

We drove west out of León toward the Pacific. Isabella slept up front, coming down off a sugar and carb high, while Paulina and I sat in the back. When we were out of town, she said, “Your friend played a card game here a week ago. He was drinking a lot and is not a very good cardplayer. Paulo talked to a man who tended bar in the game. You were right, he lost his truck to the foreman. Later in the game, in a—” Her face contorted. “Twice or zero?”

“Double or nothing?”

“That’s it. He was caught cheating, tried to run and steal back his own truck so the foreman—who is a big strong man—roughed him up. After that, your friend went to the beach. He was there yesterday. That’s all we know.”

San Cristóbal loomed behind us. White smoke spiraling through a blue sky into the stratosphere.

She pressed me. “Does that sound like your friend?”

I hesitated. “Yes.”

“He does not sound like a good man.”

“Sometimes…people have some help becoming like that.”

Leena chewed on my answer, which I was learning was her process. She thought before she spoke, although I didn’t confuse thoughtfulness with hesitancy. She was not afraid to speak. The wind tugged at her hair and skirt and dried the sweat on her skin. I’d not told her this—as I had no reason—but Leena was one of the more beautiful people I’d ever known, much less seen, and I’d known some beautiful women in my life. Amanda was petite, polished, fashion minded and design savvy, quick to speak, and striking. Shelly was taller, more natural in her appearance, more attracted to the shadow than the spotlight, comfortable in loose-fitting scrubs, and well-suited to both the operating room and the beach. Leena was something of a combination of the two. As tough as her environment demanded, tender at the drop of a hat; quick to speak but more apt to listen; modest in her dress but also comfortable in her confidence; beautiful not only in silence and passing glance, but even more so in action. Leena also possessed the one thing that neither Amanda nor Shelly did: presence. She commanded authority because she was first and foremost ready to serve those around her. She’d earned it. Her willingness to kneel down and clean the groin and bottom of a feces– and urine-soaked man, then kiss his forehead, put her on a pedestal unlike any other. I did not feel comfortable around her not because she made me feel uncomfortable, but because I felt counterfeit. Her willingness to stop, kneel, and serve amid filthy, embarrassing, and uncomfortable situations jarred something loose in me because I wasn’t. I’d spent my life pursuing my comfort, not others’. Leena had not. A strange emotion shadowed me as we bumped down dirt roads in the middle of nowhere. I did not know what to call it, but “unworthy” came about as close as anything. The second emotion was a question: How could someone so pure and selfless sit inches from someone so stained and selfish?

* * *

After an hour’s worth of driving dusty, potholed dirt roads, lined mostly with sugarcane nearing twelve feet high, we turned down a coquina-layered drive where the smell of salt and the sound of seagulls wrapped around us. A half mile later, we arrived at a small resort on the beach: a row of concrete bungalows, hammocks stretched between the columns, surfboards leaning against every available wall, various bathing suits hung out to dry on laundry lines, a man and woman floating on inflatables in the pool, cold beer in their hands with limes in the tops and condensation running down the sides, four tanned guys with sun-bleached hair sitting on chairs staring out across a relatively flat ocean. An American guy about my age—beer belly, reading glasses on his nose, bathing suit faded, barefoot with Hawaiian shirt unbuttoned—was scurrying between the rooms and serving patrons in the pool. When he saw us, he raised a hand and said in a Midwestern accent, “Be right with you.”

While we waited, Isabella walked around the pool. Eyeing it. Paulo, Paulina, and I stood beneath an umbrella, waiting.

Moments later, the guy appeared in front of me, sweating, breathing heavy, and smiling. “What can I do for you folks?”

I showed him the picture of Zaul that I’d taken from the kitchen sink at Colin’s house. “You seen this guy?”

He nodded and palmed the sweat off his head, flinging it onto the ground. He was not happy to see the picture. He squinted at me. “Sure have.”

“Mind telling me when?”

“Most of last night. Then this morning.”

“Here?”

He pointed at one of the bungalows, then around the pool. “He and his friends—if you can call them that—trashed my villa, partied at the pool till almost daylight, and ran off a couple of my guests. I’m just now getting the mess cleaned up.”

“Is he still around?”

“I sincerely hope not.”

“Any idea if he plans to return?”

“I told them if they did that I’d shoot them on sight.”

“That bad, huh?”

“They destroyed a brand-new flat screen, and I lost three extended-stay couples. Two had booked for a week. One for a month. I don’t do business with kids like him as I can usually sniff them out, but the girl that works for me took the reservation.”

“Any idea where they went?”

He pointed out in the ocean. “They hired a charter to take them to the reef. Some big swells out there the last few days. Almost twenty feet.”

“You know where they caught that charter?”

“Nope.”

“Do you know if they had transportation? A car or anything?”

He stuck his thumb in the air. “Best I could tell, they were hitchhiking, which can be tough when you’ve got five guys with boards.”

“Would you mind calling me if you happen to see them again?”

“Not if you don’t mind if I shoot them first.”

I turned to Paulina. “Can I give him your cell number?”

Paulina gave the man her number and he returned to his office. Paulo turned the truck around, and we were loading up when Paulina discovered that Isabella was not in the truck. We turned toward the water and found that she’d walked across the sand to what looked like the end of the yard and the beginning of the dune before the beach. Paulina hollered and told her to get in the truck. Isabella stood, staring at the ocean.

Paulina hollered again, but still no reaction.

I said, “She okay?”

“Yes, she’s just never seen the ocean before. I told her we’d come back when we had more—”

I hopped out of the truck and walked up next to Isabella, who was wide-eyed and chewing on a fingernail. The wind was blowing in her face and amplifying the sound of the waves crashing on the beach. I held out my hand. “Come on.” She took it and we walked the well-worn surfer’s path toward the beach. When we got there, I kicked off my flip-flops, as did she, and we walked down toward the water. The surf pounded the sand and, to her amazement, rolled up and across her toes, bathing her feet in sand and small shells. The Pacific was cool, dark blue, and she stood speechless as the water washed up and back. Wave after wave. A moment later, Paulina stood to her left and whispered, “Careful. She can’t swim.”

I’d never considered that. Isabella walked a few feet toward the waves. Knee-high. Almost midthigh. I spoke more to myself than Paulina. “What kind of kid doesn’t know how to swim?”

Paulina spoke to me while staring at Isabella. Ready to pounce. “The kind who’s never had access to water and never been taught.”

Isabella turned, delight on her face, and walked out of the water.

I spoke again. “We need to remedy that.”

Paulina glanced at me but said nothing.

* * *

We climbed into the truck and were rolling out the driveway when I tapped on the hood of the cab and said, “Give me one second.” I found the man in his office, talking on the phone. When he hung up, I asked, “How much do you figure that crew cost you?”

He was still irritated but he calculated anyway. “Four-hundred-dollar TV. Two of the couples were a week at sixty dollars a night. Other couple was here a month. I gave them a rate.” He tilted his head. “Two thousand seven hundred dollars—give or take.”

I counted out thirty hundred-dollar bills and handed them to him. He looked at me like I’d lost my mind. “I’m…sorry for your trouble.”

Eyes wide, jaw hanging halfway open, he stuffed the money in his pocket and followed me out to the truck. “Mister?”

I turned.

He pointed to the picture of Zaul in my pocket. “You know that kid?”

“Yes.”

“He important to you?”

“Yes.”

He squinted against the sun and hesitated before he spoke—as if doing so was painful. “You know, he’s real different than you.”

“I had a lot to do with making him the way he is.” I waved my hand across his resort. “If you want to blame someone for this, you can blame me.”

He held up the piece of paper on which he wrote Paulina’s number. “I’ll call if I see him again, but chances are—” He shook his head.

* * *

After Paulo had shifted into fourth, Isabella had fallen asleep in the front seat, and the wind had dried the sweat and salt and sun on our faces, Paulina nodded back toward the resort and asked through hand-shaded eyes, “What’d you do in there?”

“Asked him a few questions about Zaul.”

“And?”

“He told me.”

“And?”

“That’s it.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah.”

I don’t think she believed me, but I wasn’t willing to tell her the truth.

* * *

At my hotel, I paid my bill, tipped the attendant twenty dollars, and pulled my bike around front. Isabella’s eyes grew wide and round when she saw me sitting on it. She turned to Paulina and asked without asking. Paulina tried to shake her head without my seeing, thinking I’d be bothered by her. I spoke softly. “If you don’t mind, I don’t.”

Isabella needed nothing further. She stood next to the bike with her arms in the air. I asked Paulina, “You know how to drive?”

“Yes,” she said matter-of-factly.

I stepped off the bike and held it by the bar, motioning for her to ride. She smiled, stepped out of the truck, and straddled the bike, hiking up her skirt and then tucking it tightly beneath her thighs so the wind didn’t pull a Marilyn Monroe on her. I lifted Isabella up and she sat on the indentation between the tank and the seat. I gave my Costas to Paulina and buckled my helmet on Isabella, pulling the shield down over her eyes to keep the bugs out.

Paulo drove the speed limit while Paulina followed us. Isabella’s smile covered the entire inside of the helmet and Paulina’s spread nearly as wide. I sat up front in the truck with Paulo—in the cab with no air-conditioning. Where it was a hundred and twenty degrees if it was anything. My sweat—trickling down my face, neck, back, and calves—stuck me to the seat like honey while Paulo, seemingly unfazed, drove in relative comfort.

Halfway home, he pulled up near a roadside store advertising cell phones and prepaid cards. He motioned for me to follow. I did. When we reached the counter, he bought a new prepaid card for his own phone and then pointed at the phones in the counter. “You buy?”

He was right. A good idea. Paulo helped me negotiate with the man for a new phone and a calling card. After we’d paid, he dialed my number in his phone and watched as my phone rang. Knowing he could now get in touch with me, he nodded and waved me onward. “Vámonos.”

Paulina was right. If you needed something done, Paulo was your man.

Back in the truck, the heat returned and stuck my clothing to my skin beneath a layer of sweat. Paulo was growing more comfortable with me so every few minutes, he’d point through the windshield at something he wanted me to see or know or understand. And while I didn’t understand a word he said as he unconsciously rattled off in Spanish, I do know that the words he spoke were beautiful. Tender. Paulo was attempting to share his world with me.

Over the next thirty minutes, I kept an eye on the girls in the rearview, listened to Paulo, nodded as if I understood completely, and lost five pounds in sweat.

It was a great conversation.

* * *

After dinner, I used my new phone to call Colin’s house line. He picked up after the first ring. I said, “Ronnie?” and hung up.

Colin got a new SIM card every couple of days and nobody ever knew the number—because it wasn’t intended for incoming calls. If I needed to talk with him, I called his house number and said the name of any president and hung up. That left him to call the number on his caller ID. Which he did. We’d had a decade’s worth of practice. Seconds later, my phone rang and I answered. “How you guys getting along?”

“Better.” His voice sounded different. Even some levity. He also spoke softly, which led me to believe that someone was sleeping nearby. He was almost whispering. “Small progress, but it’s progress. Any luck?”

“Some.” I backed up and told him about León. About Isabella, Paulo, the coffee plantation, his truck, and then the beach resort. He was quiet when I finished.

He said, “Any idea what’s next?”

“Tomorrow I thought I’d get on the bike and ride up and down the coast. Surfers are particular about their waves so it shouldn’t be too tough. Find good waves and I should find some surfers. Provided he’s still with them.”

“You think he’s not?”

“I think Zaul will be of use to these guys as long as he has money. He’s lost his transportation and I’d bet he’s running low on money, so I’m guessing his usefulness is running out—if it hasn’t already.”

Colin mumbled in agreement. I tried to change the subject. “Any sign of Shelly?”

“She’s been to see Maria every day. The reconstruction of her face was nothing short of miraculous. She stops in on her way home.”

That sounded strange because Colin’s house wasn’t on Shelly’s way home. My silence told Colin I was trying to figure this out. He picked up on it. “She’s…spending some time with an orthopedist from the hospital. When I asked about him, she said, ‘He’s a safe bet.’ He’s got a place down on the canal.”

I did not see that one coming. “I hope she’s happy.”

Colin cleared his throat. “He heard she’d called off the wedding and showed up at her work. Took her to dinner. All the nurses say she seems happier.”

“I hope she is.”

“She looks different. Peaceful.”

I could hear a noise in the background. I was scratching my head when Colin said, “Hold on. Somebody wants to talk to you.”

He handed her the phone. Maria sounded sleepy. Her words sounded thick, like she’d just come from the dentist and the Novocain had yet to wear off. “Hey, Uncle Charlie. I miss you.”

“I miss you, pretty girl. How you feeling?”

“Okay. It hurts less. You find Zaul?”

“Not yet, but I’m looking. He was always pretty good at hide-and-go-seek.”

She chuckled. “I remember. Uncle Charlie?”

“Yeah, baby girl.”

“When you find him, hug him for me. We all miss him. Mom cries most of the time now.”

I swallowed hard. “You heal up. I’ll see you soon.”

“You bring me something?”

“You bet.”

She handed the phone back to her dad. Colin and I sat in silence. After a minute, I broke it. “That one’s special.”

He sniffled. Blew his nose. “I been thinking a lot lately and I can’t figure something.”

“What’s that?”

“Why was one like her given to someone like me?”

It was a good question, and I’d been wrestling with many of the same emotions. I had no answer for him. “I’ll call when I know more.”

I hung up, lay on my bed, and listened to the night. People talked in hushed tones in their homes around us. Dogs barked. Pigs grunted. A horse neighed in one direction and a noisy cat screeched in another. Every few moments, I heard a thud on the ground outside. Finally, I heard one on the tin roof of the chicken coop, which, when it landed, sounded like a bomb going off above my head and levitated me about four feet above the bed. I walked outside in the moonlight and stared up into the tree. A monkey was pulling on the mangoes and dropping them to the ground where several dogs had gathered. When I walked beneath the tree, he sat up straight, staring down at me. I picked through the mangoes, finding one that felt ripe, and washed it in the pila. After washing Paulina’s knife, I peeled it, placed the slices on my tongue, and let the taste swirl around, filling me. Between the aroma, the taste, the juice, the texture, it was an all-encompassing experience.

That mango was a mirror image of my last few days. Once beautiful, placed on display for all the world to see, it had been ripped from its perch, thrown to the ground, rolled in manure and squalor, and left to rot. While that might have bruised it and soiled its skin, it didn’t change its nature or what it freely offered, for once I peeled it back, an inexplicable sweetness was waiting to be discovered and tasted and consumed. There was just one catch—you had to be willing to get your hands dirty. Even sticky. To pick through it. Bathe it. Peel it back. And for so much of my life I had not.

The second train of thought coursing through my mind was a quiet nagging. Whether I found Zaul or not, what was I going to do? At some point, this search would end, and when it did, where would I go? What would I do? Who, if anyone, would I do it with? Hack was dead. Bimini held nothing for me. Miami had never been my home. While I’d been born there and while I still owned a house, Jacksonville wasn’t my home. I felt no tug anywhere in the States. No one was expecting me. No one was waiting by the phone. If I didn’t show up somewhere, no one would know or care.

The fruit of my life was that there was none.

I finished the mango; climbed up on the tin roof, which was still warm from the day’s heat; and lay down, staring at the stars and counting the satellites that screamed overhead.

An hour later, I climbed down, having never felt so full and so small at the same time.