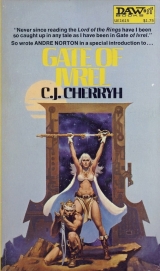

Текст книги "Gate of Ivrel"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

"Ask Morgaine," Vanye said again; and when his breathing space grew less and an edge rested familiarly on his shoulder, he maintained his composure and did not flinch, though his heart was beating fit to burst. "If you continue, Chya Roh, I shall decide there is no honor at all in Chya.

And I shall be ashamed for that."

Roh considered him in silence. Vanye went sick inside: his nerves were strung, Waiting, the least pressure from them likely to send from his lips a shout to raise the hall and Morgaine from sleep. He was not brave. He had long ago discovered in himself that he had no courage for enduring pain or threat. His brothers had discovered that in him before he had. It was the same feeling that churned in him now, the same that he had known when they, out of old San Romen's protective witness, had bullied him to his knees and" brought tears to his eyes. That one fatal time he had seized arms against Kandrys' tormenting of him, one time only: his hands had killed, not his mind, which was blank and terrified, and had his hands not 89

Gate of Ivrel

been filled with a weapon they would have found him as always, as he was now.

But Roh snapped his fingers a second time and they let him alone. "Get to your place," said Roh, "ilin."

He rose then, and bowed, and walked– it was incredible that he could walk steadily– to the place he had left at the hearth. There he lay down again, and wrapped himself in his cloak and clenched his teeth and let the fire warm the tremors from his muscles.

He wanted to kill. For every affront ever paid him, for all the terror ever set into him, he wanted to kill; and he squeezed the tears from his eyes and began to reckon that perhaps his father had been right, that his hand had been more honest than he knew. He feared a great many things: he feared death; he feared Morgaine and he feared Liell and the madness of Kasedre; but there never was fear such as there was in being alone among kinsmen, among whom he was always bastard and outcast.

Once, when he was a child, Kandrys and Erji had lured him into the storage basements of Ra-morij, and there overpowered him and hung him from a beam in the deep cellars, alone in the dark and with the rats. They had only come after him after the blood had left his hands and he could not find the strength to scream any longer. Then they had come with lights, and cut him down, hovering over him white-faced and terrified for fear that they had killed him. Afterward they had threatened worse if he showed the cruel marks the ropes had made.

He had not complained to anyone. He had learned the conditions of his welcome in Nhi even then, had learned to clutch his scraps of honor to himself in silence, had practiced, had bit his lip and kept his own counsel, until he had fairly won the honor of the warrior's braid, and until the demands of uyinhonor must keep Kandrys and Erij from their more petty tormentings of him.

But the looks were there, the subtle, hating looks and secret contempt that became evident when he committed any error that cost him honor.

90

Gate of Ivrel

Even the Chya tried him, in the same way– scented fear and went for it, like wolves to a deer.

Yet something there was in him that yearned to like the lord of Chya, this man so like himself, that showed kindred blood in his face and in his bearing. Roh was legitimate: Roh's father had virtually abandoned the lady Ilel to her fate, captive and bearing Rijan's bastard, that must in nowise return to confound the purity of Chya– to contest with his son Roh.

And Chya both feared him, and scented fear, and would have gone for his throat if not for their debt to Morgaine.

Late, late into the long night, his not-quite-rest was disturbed by a booted foot crunching a cinder not far from his head, and he came up on his arm as Roh dropped to his haunches looking down at him. In panic he reached for the sword beside him; Roth clamped his hand down on the hilt, preventing him.

"You came from Leth," said Roh softly. "Where did you meet her?"

"At Aenor-Pyvvn." He sat up, tucked his feet under him, tossed the loose hair from his eyes. "And I still say, ask Morgaine her business, not her servant."

Roh nodded slowly. "I can guess some things. That she still purposes what she always did, whatever it was. She will be the death of you, Nhi Vanye i Chya. But you know that already. Take her hence as quickly as you can in the morning. We have Leth breathing at our borders this night. Reports of it have come in. Men have died. Liell will stop her if he can. And there is a limit to what service we will pay this time in Chya lives."

Vanye stared into the brown eyes of his cousin and found there a grudging acceptance of him: for the first time the man was talking to him, as if he still had the dignity of an uyoof the high clan. It was as if he had not acquitted himself so poorly after all, as if Roh acknowledged some kinship between them. He drew a deep breath and let it go again.

"What do you know of Liell?" he asked of Roh. "Is he Chya?"

91

Gate of Ivrel

"There was a Chya Liell," said Roh. "And our Liell was a good man, before he became counselor in Leth." Roh looked down at the stones and up again, his face drawn in loathing. "I do not know. There are rumors it is the same man. There are rumors he in Leth is qujal.That he– like Thiye of Hjemur– is old.What I can tell you is that he is the power in Leth, but if you have come from Leth, you know that. At times he is a quiet enemy, and when the worst beasts have come into Koris-wood, the worst sendings of Thiye, Liell's folk have been no less zealous than we to rid Koris of the plague: we observe hunter's peace on occasion, for our mutual good. But our harboring Morgaine will not better relations between Leth and Chya."

"I believe your rumors," said Vanye at last. Coldness rested in his belly, when he thought back to the lakeshore.

"I did not," said Roh, "until this night, that shecame into hall."

"We will go in the morning," said Vanye.

Roh stared into his face yet a moment more. "There is Chya in you," he said. "Cousin, I pity you, your fate. How long have you to go of your service with her?"

"My year," he said, "has only begun."

And there passed between them the silent communication that that year would be his last, accepted with a sorrowful shake of Roh's head.

"If so happen," said Roh, "if so happen you find yourself free– return to Chya."

And before Vanye could answer anything, Roh had walked off, retiring to a distant corridor of the rambling hall that led to other huts, warrenlike.

He was shaken then by the thing that he had never dreamed to receive: Chya would take him in.

In a way it was only cruelty. He would die before his year was out.

Morgaine was death-prone, and he would follow; and in it he had no choice. A moment ago he had had no particular hope.

92

Gate of Ivrel

Only now there was. He looked about at the hall, surely one of the strangest of all holds in Andur-Kursh. Here was refuge, and welcome, and a life.

A woman. Children. Honor.

These were not his, and would not be. He turned and clasped his arms about his knees, staring desolately into the fire. Even should she die, which was probably the thought in Roh's mind, he had his further bond, to ruin Hjemur.

If so happen you find yourself free.

In all the history of man, Hjemur had never fallen.

93

Gate of Ivrel

Chapter 6

The whole of Chya seemed to have turned out in the morning to see them leave, as silent at their going as they had been at their arrival; and yet there seemed no ill feeling about them now that Roh attended them to their horses, and himself held the stirrup for Morgaine to mount.

Roh bowed most courteously when Morgaine was in the saddle, and spoke loudly enough in wishing her well that the whole of Chya could hear. "We will watch your backtrail at least," he said, "so that I do not think you will have anyone following you through Chya territories very quickly. Be mindful of our safety too, lady."

Morgaine bowed from the saddle. "We are grateful, Chya Roh, to you and all your people. Neither of us has slept secure until we slept under your roof. Peace on your house, Chya Roh."

And with that she turned and rode away, Vanye after her, amid a great murmuring of the people. And as at their coming, so at their going, the children of Chya were their escort, running along beside the horses, heedless of the proprieties of their elders. There was wild excitement in their eyes to see the old days come to life, that they had heard in songs and ballads. They did not at all seem to fear or hate her, and with the delightedness of childhood took this great wonder as primarily for their benefit.

It was, Vanye thought, that she was so fair it was hard for them to think ill of her. She shone in sunlight, like sun on ice.

"Morgaine!" they called at her, softly, as Chya always spoke, "Morgaine!"

And at last even her heart was touched, and she waved at them, and smiled, briefly.

Then she laid heels to Siptah, and they left the pleasant hall behind, with all the warmth of Chya in the sunlight. The forest closed in again, chilling their hearts with its shadow, and for a very long time they both were silent.

94

Gate of Ivrel

He did not even speak to her the wish of his heart, that they turn and go back to Chya, where there was at least the hope of welcome. There was none for her. Perhaps it was that, he thought, that made her face so downcast throughout the morning.

As the day went on, he knew of a certainty that it was not the darkness of the woods that bore upon her heart. Once they heard a strange wild cry through the branches, and she looked up, such an expression on her face as one might have who had been distracted from some deep and private grief, bewildered, as if she had forgotten where she was.

That night they camped in the thick of the wood. Morgaine gathered the wood for the fire herself, making it small, for these were woods where it was not well to draw visitors. And she laughed sometimes and spoke with him, a banality he was not accustomed to in her: the laughter had no true ring, and at times she would look at him in such a way that he knew he lay near the center of her thoughts.

It filled him with unease. He could not laugh in turn; and he stared at her finally, and then suddenly bowed himself to the earth, like one asking grace.

She did not speak, only stared back at him when he had risen up, and had the look of one unmasked, looking truth back, if he could know how to read it.

Questions trembled on his lips, He could not sort out one that he dared ask, that he did not think would meet some cold rebuff or what was more likely, silence.

"Go to sleep," she bade him then.

He bowed his head and retreated to his place, and did so, until his watch.

Her mood had passed by the morning. She smiled, lightly enough, talked with him over breakfast about old friends– hers: of the King. Tiffwy, how his son had been, of the lady who was his wife. It was that kind of thing one might hear from old people, talk of folk long dead, not shared 95

Gate of Ivrel

with the young; the worse thing was that she seemed to know it, and her gray eyes grew wistful, and searched his, seeking understanding, some small appreciation of the only things she knew how to say with him.

"Tiffwy," he said, "must have been a great man. I would like to have known him."

"Immortality," she said, "would be unbearable except among immortals."

And she smiled, but he saw through it.

She was silent thereafter, and seemed downcast, even while they rode. She thought much. He still did not know how to enter those moods. She was locked within herself.

It was as if he had snapped whatever thin cord bound them by that word: I would like to have known him.She had detected the pity. She would not have it of him.

By evening they could see the hills, as the forest gave way to scattered meadows. In the west rose the great mass of Alis Kaje, its peaks white with snow: Alis Kaje, the barrier behind which lay Morija. Vanye looked at it as a stranger to this side of the mountain wall, and found all the view unfamiliar to him, save great Mount Proeth, but it was a view of home.

And thereafter the land opened more to the north and they stood still upon a hillside looking out upon the great northern range.

Ivrel.

The mountain was not so tall as Proeth, but it was fair to the eye and perfect, a tapering cone equal to left and to right. Beyond it rose other mountains, the Kath Vrej and Kath Svejur, fading away into distance, the ramparts of frosty Hjemur. But Ivrel was unique among all mountains.

The little snow there was atop it capped merely the summit: most of its slopes were dark, or green with forests.

And at its base, unseen in the distance that made Ivrel itself seem to drift at the edge of the sky, lay Irien.

96

Gate of Ivrel

Morgaine touched heels to Siptah, startled the horse into motion, and they rode on, downslope and up again, and she spoke never a word. She gave no sign of stopping even while stars brightened in the sky and the moon came up.

Ivrel loomed nearer. Its white cone shone in the moonlight like a vision.

"Lady." Vanye leaned from his saddle at last, caught the reins of the gray.

"Liyo,forbear. Irien is no place to ride at night. Let us stop."

She yielded then. It surprised him. She chose a place and dismounted, and took her gear from Siptah. Then she sank down and wrapped herself in her cloak, caring for nothing else. Vanye hurried about trying to make a comfortable camp for her. These things he was anxious to do: her dejection weighed upon his own soul, and he could not be comfortable with her.

It was of no avail. She warmed herself at the fire, and stared into the embers, without appetite for the meal he cooked for her, but she picked at it dutifully, and finished it.

He looked up at the mountain that hung over them, and felt its menace himself. This was cursed ground. There was no sane man of Andur-Kursh would camp where they had camped, so near to Irien and to Ivrel.

"Vanye," she said suddenly, "do you fear this place?"

"I do not like it," he answered. "—Yes, I fear it."

"I laid on you at Claiming to ruin Hjemur if I cannot. Have you any knowledge where Hjemur's hold lies?"

He lifted a hand, vaguely toward the notch at Ivrel's base. "There, through that pass."

"There is a road there, that would lead you there. There is no other, at least there was not."

97

Gate of Ivrel

"Do you plan," he asked, "that I shall have to do this thing?"

"No," she said. "But that may well be."

Thereafter she gathered up her cloak and settled herself for the first watch, and Vanye sought his own rest.

It seemed only a moment until she leaned over him, touching his shoulder, quietly bidding him take his turn: he had been tired, and had slept soundly.

The stars had turned about in their nightly course.

"There have been small prowlers," she said, "some of unpleasant aspect, but no real harm. I have let the fire die, of purpose."

He indicated his understanding, and saw with relief that she sought her furs again like one who was glad to sleep. He put himself by the dying fire, knees drawn up and arms propped on his sheathed sword, dreaming into the embers and listening to the peaceful sounds of the horses, whose sense made them better sentinels than men.

And eventually, lulled by the steady snap of the cooling embers, the whisper of wind through the trees at their side, and the slow moving of the horses, he began to struggle against his own urge to sleep.

She screamed.

He came up with sword in hand, saw Morgaine struggling up to her side, and his first thought was that she had been bitten by something. He bent by her, seized her up and held her by the arms and held her, she trembling.

But she thrust him back, and walked away from him, arms folded as against a chill wind; so she stood for a time.

"Liyo?"he questioned her.

"Go back to sleep," she said. "It was a dream, an old one."

"Liyo—"

98

Gate of Ivrel

"Thee has a place, ilin.Go to it."

He knew better than to be wounded by the tone: it came from some deep hurt of her own; but it stung, all the same. He returned to the fireside and wrapped himself again in his cloak. It was a long time before she had gained control of herself again, and turned and sought the place she had left. He lowered his eyes to the fire, so that he need not look at her; but she would have it otherwise: she paused by him, looking down.

"Vanye," she said, "I am sorry."

"I am sorry too, liyo."

"Go to sleep. I will stay awake a while."

"I am full awake, liyo.There is no need."

"I said a thing to you I did not mean."

He made a half-bow, still not looking at her. "I am ilin,and it is true I have a place, with the ashes of your fire, liyo,but usually I enjoy more honor than that, and I am content."

"Vanye." She sank down to sit by the fire too, shivering in the wind, without her cloak. "I need you. This road would be intolerable without you."

He was sorry for her then. There were tears in her voice; of a sudden he did not want to see the result of them. He bowed, as low as convenience would let him, and stayed so until he thought she would have caught her breath. Then he ventured to look her in the eyes.

"What can I do for you?" he asked.

"I have named that," she said. It was again the Morgaine he knew, well armored, gray eyes steady.

"You will not trust me."

99

Gate of Ivrel

"Vanye, do not meddle with me. I would kill you too if it were necessary to set me at Ivrel."

"I know it," he said. "Liyo,I would that you had listened to me. I know you would kill yourself to reach Ivrel, and probably you will kill us both. I do not like this place. But there is no reasoning with you. I have known that from the beginning. I swear that if you would listen to me, if you would let me, I would take you safely out of Andur-Kursh, to—"

"You have already said it. There is no reasoning with me."

"Why?" he asked of her. "Lady, this is madness, this war of yours. It was lost once. I do not want to die."

"Neither did they," she said, and her lips were a thin, hard line. "I heard the things they said of me in Baien, before I passed from that time to this.

And I think that is the way I will be remembered. But I will go there, all the same, and that is my business. Your oath does not say that you have to agree with what I do."

"No," he acknowledged. But he did not think she heard him: she gazed off into the dark, toward Ivrel, toward Irien. A question weighed upon him.

He did not want to hurt her, asking it; but he could not go nearer Irien without it growing heavier in him.

"What became of them?" he asked. "Why were there so few found after Irien?"

"It was the wind," she said.

"Liyo?"Her answer chilled him, like sudden madness. But she pressed her lips together and then looked at him.

"It was the wind," she said again. "There was a gate-field there– warping down from Ivrel– and the mist there was that morning whipped into it like smoke up a chimney, a wind… a wind the like of which you do not imagine. That was what passed Irien. Ten thousand men– sent through.

Into nothing. Weknew, my friends and I, we five; we knew, and I do not 100

Gate of Ivrel

know whether it was more terrible for us knowing what was about to happen to us than for those that did not understand at all. There was only starry dark there. Only void in the mists… But I lived of course. I was the only one far back enough: it was my task to circle Irien, Lrie and the men of Leth and I– and when we were on the height, it began. I could not hold my men; they thought that they could aid those below, with their king, and they rode down; they would not listen to me, you see, because I am a woman. They thought that I was afraid, and because they were men and must not be, they went. I could not make them understand, and I could not follow them." Her voice faltered; she steadied it. "I was too wise to go, you see. I am civilized; I knew better. And while I was being wise– it was too late. The wind came over us. For a moment one could not breathe.

There was no air. And then it passed, and I coaxed poor Siptah to his feet, and I do not clearly remember what I did after, except that I rode toward Ivrel. There was a Hjemurn force in my way. I fell back and back then, and there was only the south left open. Koris held a time. Then I lost that shelter; and I retreated to Leth and sheltered there a time before I retreated again toward Aenor-Pyvvn. I meant to raise an army there; but they would not hear me. When they came to kill me, I cast myself into the Gate: I had no other refuge left. I did not know it would be so long a wait."

"Lady," he said, "this– this thing that was done at Irien, killing men without a blow being struck… when we go there, could not Thiye send this wind down on us too?"

"If he knew the moment of our coming, yes. The wind– the wind was the very air rushing into that open Gate, a field cast to the Standing Stone in Irien. It opened some gulf between the stars. To maintain it extended more than a moment as it was would have been disaster to Hjemur. Even he could not be that reckless."

"Then, at Irien– he knew."

"Yes, he knew." Morgaine's face grew hard again. "There was one man who began to go with us, who never stood with us at Irien– he that wanted Tiffwy's power, that betrayed Tiffwy with Tiffwy's wife– that later stood tutor of Edjnel's son, after killing Edjnel."

"Chya Zri."

101

Gate of Ivrel

"Aye, Zri, and to the end of my days I will believe it, though if it was so he was sadly paid by Hjemur. He aimed at a kingdom, and the one he had of it was not the one he planned."

"Liell." Vanye uttered the name almost without thinking it, and felt the sudden impact of her eyes upon his.

"What makes you think of him?"

"Roh said that there was question about the man. That Liell is… that he is old, liyo,that he is old as Thiye is old."

Morgaine's look grew intensely troubled. "Zri and Liell. Singularly without originality, to have drowned all the heirs of Leth– if drowned they were."

He remembered the Gate shimmering above the lake, and knew what she meant. Doubts assailed him. He ventured a question he fully hated to ask.

"Could you– live by this means, if you wished?"

"Yes," she answered him.

"Have you?"

"No," she said. And, as if she read the thing in his mind: "It is by means of the Gates that it is done, and it is no light thing to take another body. I am not sure myself quite how it is done, although I think that I know. It is ugly: the body must come from someone, you see. And Liell, if that is true, is growing old."

He shivered, remembering the touch of Liell's fingers upon his arm, the hunger– he read it for hunger even then– within his eyes. Come with me and I will show you,he had said. She will have the soul from you before she is done. Come with me, Chya Vanye. She lies. She has lied before.

Come with me.

102

Gate of Ivrel

He breathed an oath, a prayer, something, and stumbled to his feet, to stand apart a moment, sick with horror, sensitive for the first time to his youth, his trained strength, as something that had been the object of covetousness.

He felt unclean.

"Vanye," she said, concern in her voice.

"They say," he managed then, turning to look at her, "that Thiye is aging too– that he has the look of an old man."

"If," she said levelly, "I am dead or lost and you go against Hjemur alone– do not consider being taken prisoner there. I would not by any means, Vanye."

"Oh Heaven," he murmured. Bile rose in his throat. Of a sudden he began to comprehend the stakes in these wars of qujaland men, and the prize there was for losing. He stared at her– he knew, like the veriest innocent, and met a lack of all proper horror.

"Would you do this?" he asked.

"I think that one day," she said, "to do what I must do, I would have to consider it."

He swore. For a very little he would have left her in that moment. She began at last to show concern of it, the smallest impulse of humanity, and it was that which held him.

"Sit down," she said. He did so.

"Vanye," she said then. "I have no leisure to be virtuous. I try, I try, with what of me there is left. But there is very little. What would you do, if you were dying, and you had only to reach out and kill– not for an extended old age, with pain, and sickness, but for another youth? For the qujalthere is nothing after, no immortality, only to die. They have lost their gods, or 103

Gate of Ivrel

lost whatever belief they ever had. That is all there is for them– to live, to enjoy pleasure– to enjoy power."

"Did you lie to me? Are you of their blood?"

"I have not. I am not qujal.But I know them. Zri… if you are right, Vanye, it explains much. Not for ambition, but of desperation: to live. To save the Gates, on which he depends. I had not looked for that in him.

What did he say to you, when he spoke with you?"

"Only that I should leave you and come with him."

"Well that you had better sense. Otherwise—"

And then her eyes grew guarded, and she took the black weapon from her belt: he thought in the first heartbeat that she had perceived some intruder, and then to his shock he saw the thing directed at him. He froze, mind blank, save of the thought that she had suddenly gone mad.

"Otherwise," she continued, "I should have had such a companion on my ride to Ivrel that would assure I did not live, such a companion as would wait until the nearness of the Gate lent him the means to deal with me—alive. I left you upon a bay mare, Chya Vanye, and you chose Liell's horse thereafter. That was who I thought it was when first I saw you riding after me, and I was not anxious for Liell's company alone. I was surprised to realize that it was you, instead."

"Lady," he exclaimed, holding forth his hands to show them empty of threat. "I have sworn to you… lady, I have not deceived you. Surely– it could not happen, it could not happen and I not know it. I would know, would I not?"

She arose, still watching him, constantly watching him, and drew back to the place where rested her cloak and her sword.

"Saddle my horse," she bade him.

104

Gate of Ivrel

He went carefully, and did as she ordered him, knowing her at his back with that weapon. When he was done, he gave back for her, and she watched him carefully, even to the moment that she swung up into the saddle.

Then she reined about and toward the black horse. All at once he read her thoughts, to kill the beast and leave him afoot, since she would not kill him, ilin.

He hurled himself between, looked up with outraged horror; it was not honor to do such a thing, to abuse the ilin-oath, to kill a man's horse and leave him stranded. And for one moment there was such a look of wildness on her face that he feared she would use the weapon on him and the beast.

Suddenly she jerked Siptah's head about to the north and spurred off, leaving him behind.

He stared after her a moment, dazed, knowing her mad.

And himself likewise.

He cursed and heaved up his gear, flung saddle on the black, secured the girth, hauled himself into the saddle and went– the beast knowing full well he belonged with the gray by now. The horse needed no touch of the heel to extend himself, but ran, downhill and around a turning, across a stream and up again, overtaking the loping gray.

He half expected a bolt that would take him from the saddle or tumble his horse dead instead; Morgaine turned in the saddle and saw him come. But she allowed it, began to rein in.

"Thee is an idiot," she said when he had come alongside. And she looked then as if she could give way to tears, but she did not. She thrust the black weapon into the back of her belt, under the cloak, and looked at him and shook her head. "And thee is Kurshin. Nothing else could be so honorably stupid. Zri would surely have run, unless Zri is braver than he once was.

We are not brave, we that play this game with Gates; there is too much we 105

Gate of Ivrel

can lose, to have the luxury to be virtuous, and to be brave. I envy you, Kurshin, I do envy anyone who can afford such gestures."

He pressed his lips tightly. He felt simple, and shamed, realizing now she had tried to frighten him; none of it made sense with him– her moods, her distrust of him. His voice turned brittle. "I am easy to deceive, liyo,much more than you could be; any of your simplest tricks can amaze me, and no few of them frighten me."

She had no answer for him.

At times she looked at him in a way he did not like. The air between them had gone poisonous. Go away,the look said. Go away, I will not stop you.

He would not have left her hurt and needing him; there was oath-breaking and there was oath-breaking, and to break ilin-bond when she was able to care for herself was a heavy matter, but there was that in her manner which convinced him that she was far from reasoning.

The light grew in the sky, into a cold, dreary morning, with clouds rolling in from the north.

And early in that morning the land fell away below them and the hills opened up into the slope of Irien.

It was a broad valley, pleasant to the eye. As they stopped upon the verge of that great bowl, Vanye was not sure that this was the place. But then he saw that its other side was Ivrel, and that there was a barrenness in its center, far below. They were too far to see so fine a detail as a single Standing Stone, but he reckoned that for the center of that place.

Morgaine slid down from Siptah's back and troubled to unhook Changelingfrom its place, by which he knew she meant some long delay.

He dismounted too; but when she turned and walked some distance away along the slope he did not estimate that she meant him to follow. He sat down upon a large rock and waited, gazing into the distances of the valley.

In his mind he imagined the thousands that had ridden into it, upon one of those gray spring mornings that cloaked the valleys with mist, where men 106

Gate of Ivrel

and horses moved like ghosts in the fog– of darkness swallowing up everything, the winds, as she had said, drawing the mist like smoke up a chimney.