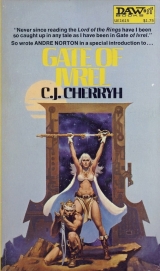

Текст книги "Gate of Ivrel"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Gate of Ivrel

The Morgaine Saga #1

C.J. Cherryh

DAW Books, Inc.

Donald A. Wollheim, Founder

375 Hudson Street,

New York, NY 10014

Elizabeth R. Wollheim

Sheila E. Gilbert

Publishers

www.dawbooks.com

in cooperation with

SEATTLE BOOK COMPANY

www.seattlebook.com

Produced by

RosettaMachine

www.rosettamachine.com

Gate of Ivrel

The Finest in

DAW Science Fiction

from C.J. CHERRYH:

THE ALLIANCE-UNION UNIVERSE

The Company Wars

DOWNBELOW STATION

The Era of Rapprochement

SERPENT'S REACH

FORTY THOUSAND IN GEHENNA

MERCHANTER'S LUCK

The Chanur Novels

THE PRIDE OF CHANUR

CHANUR'S VENTURE

THE KIF STRIKE BACK

CHANUR'S HOMECOMING

CHANUR'S LEGACY

The Mri Wars

THE FADED SUN: KESRITH

THE FADED SUN: SHON'JIR

THE FADED SUN: KUTATH

Merovingen Nights (Mri Wars period)

ANGEL WITH THE SWORD

The Age of Exploration

CUCKOO'S EGG

VOYAGER IN NIGHT

PORT ETERNITY

The Hanan Rebellion

BROTHERS OF EARTH

HUNTER OF WORLDS

ii

Gate of Ivrel

THE MORGAINE CYCLE

GATE OF IVREL (#1)

WELL OF SHIUAN (#2)

FIRES OF AZEROTH (#3)

EXILE'S GATE (#4)

THE EALDWOOD FANTASY NOVELS

THE DREAMSTONE

THE TREE OF SWORDS AND JEWELS

OTHER CHERRYH NOVELS

HESTIA

WAVE WITHOUT A SHORE

THE FOREIGNER UNIVERSE

FOREIGNER

INVADER

INHERITOR

PRECURSOR

DEFENDER*

EXPLORER*

*Forthcoming

iii

Gate of Ivrel

Copyright © 1976 by C.J. Cherryh.

All Rights Reserved.

DAW Book Collectors No. 188.

DAW Books are distributed by Penguin Putnam Inc.

Microsoft LIT edition ISBN: 0-7420-9125-2

Adobe PDF edition ISBN: 0-7420-9127-9

Palm PDB edition ISBN: 0-7420-9173-2

MobiPocket edition ISBN: 0-7420-9126-0

Ebook editions produced by

SEATTLE BOOK COMPANY

Ebook conversion and distribution powered by

www.RosettaMachine.com

All characters and events in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead is strictly coincidental.

iv

Gate of Ivrel

Electronic format made

available by arrangement with

DAW Books, Inc.

www.dawbooks.com

Elizabeth R. Wollheim

Sheila E. Gilbert

Publishers

Palm Digital Media

www.palm.com/ebooks

v

Gate of Ivrel

vi

Gate of Ivrel

Table of Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

vii

Gate of Ivrel

Prologue

1

The gates were the ruin of the qhal. They were everywhere, on every world, had been a fact of life for millennia, and had linked the whole net of qhal civilizations– an empire of both Space and Time, for the Gates led into elsewhen as well as elsewhere… except at the end.

At first the temporal aspect of the Gates had not been a matter of great concern. The technology had been discovered in the ruins of a dead world in the qhal system– a discovery that, made in the first few decades in space, suddenly opened for them the way to the stars. Thereafter ships were used only for the initial transport of technicians and equipment over distances of light-years. But after each World Gate was built, travel to that world and on its surface became instantaneous.

And more than instantaneous. Time warped in the Gate-transfer. It was possible to step from point to point across light-years, unaged, different from the real time of ships. And it was possible to select not alone where one would exit, but when– even upon the same world, projecting forward to its existence at some different point along the course of worlds and suns.

By law, there was no return in time. It had been theorized ever since the temporal aspect of the Gates was discovered, that accidents forward in time would have no worse effect than accidents in the Now; but intervention in backtime could affect whole multiples of lives and actions.

So the qhal migrated through future time, gathering in greater and greater numbers in the most distant ages. They migrated in space too, and thrust themselves insolently into the affairs of other beings, ripping loose a segment of their time also. They generally despised outworld life, even what was qhal-like and some few forms that could interbreed with qhal. If possible they hated these potential rivals most of all, and loathed the half-qhal equally, for it was not in their nature to bear with divergence. They simply used the lesser races as they were useful, and seeded the worlds they colonized with the gatherings of whatever compatible worlds they1

Gate of Ivrel

pleased. They could experiment with worlds, and jump ahead in time to see the result. They gleaned the wealth of other, non-qhal species, who plodded through the centuries at their own real-time rate, for use of the Gates was restricted to qhal. The qhal in the end had little need left, and little ambition but for luxury and novelty and the consuming lust for other, ever-farther Gates.

Until someone, somewhen, backtimed and tampered– perhaps ever so minutely.

The whole of reality warped and shredded. It began with little anomalies, accelerated massively toward time-wipe, reaching toward the ends of Gate-tampered time and Gate-spanned space.

* * *

Time rebounded, indulged in several settling ripples of distortion, and

centered at some point before the over-extended Now.

* * *

At least, so the theorists from the Science Bureau surmised, when the

worlds that survived were discovered, along with their flotsam of qhal

relics that had been cast back up out of time. And among the relics were

the Gates.

2

The Gates exist. We can therefore assume that they exist in the future and in the past, but we cannot ascertain the extent of their existence until we use them. According to present qhal belief, which is without substantiation, world upon world has been disrupted; and upon such worlds elements are greatly muddled. Among these anomalies may be survivals taken from our own area, which might prove lethal to us if taken into backtime.

2

Gate of Ivrel

It is the Bureau's opinion that the Gates, once passed, must be sealed from the far side of space and time, or we continually risk the possibility of another such time-implosion as ruined the qhal. It is theorized by the qhal themselves that this area of space has witnessed one prior time-implosion of undetermined magnitude, perhaps of a few years of span or of millennia, which was occasioned by the first Gate and receptor discovered by the qhal, to the ruin first of the unknown alien culture and subsequently of their own. There is therefore a constant risk so long as there will ever exist a single Gate, that our own existence could be similarly affected upon any instant. It is therefore the majority opinion of the Bureau that utilization of the Gates should be permitted, but only for the dispatch of a force to close them, or destroy them. A team has been prepared. Return for them will of course be impossible; and the length of the mission will be of indeterminate duration, so that, on the one hand, it may result in the immediate entrapment or destruction of the team, or, on the other, it may prove to be a task of such temporal scope that one or a dozen generations of the expeditionary force may not be sufficient to reach the ultimate Gate.

Journal, Union Science Bureau, Vol. XXX, p. 22

3

Upon the height of Ivrel standen Staines y-carven with sich qujalish Runes, the which if man touche, given forth sich fires of witcherie as taken soul and bodie withal. To all these Places of Powers, grete forces move, the which qujalish sorceries yet werken. Ye may knowe qujalish blude herewith, if childe be born of gray eyen, in stature considerable, and if he flee gude and seek after sich Places, for qujal lacken soules, and yet by sorceries liven faire and younge more yeares than Men.

—Book of Embry, Hait-an-Koris

4

In the year 1431 of the Common Reckoning, there arose War between the princes of Aenor, Koris, Baien, and Korissith, against the hold of Hjemur-beyond-Ivrel. In that year the lord of Hjemur was the witch-lord Thiye son of Thiye, lord of Rahjemur, lord of Ivrel of the Fires, which shadows Irien.

3

Gate of Ivrel

Now in this time there came to the exiled lord of Koris, Chya Tiffwy son of Han, certain five Strangers whose like was never before seen in the land.

They gave that they had come from the great Southe, and made themselves hearth-welcome with Chya Tiffwy and the lord of Aenor, Ris Gyr son of Leleolm. Now it was clearly observed that One of these five strangers was surely of Qujalin blood, being a woman of pale coloring and stature as great as most ordinary Men, while Another of the partie was of golden coloring, yet withal not unlike unto such as be born by Nature in Koris of Andur, the others being dark and seeming men. Now surely the eyes of both Gyr and Tiffwy were blinded by their great Desire, they being sisters'

sons, and Tiffwy's kingdom being held by the lord from Ivrel of the Fires.

Then persuaded they by great Oaths and promises of rewardes the lords of Baien-an, the chiefest among whom was also Cousin to them, this being lord Seo, third brother's son of the great Andur-lord Rus. And of Horse they gathered seven thousands and of Foot three thousands, and with the promises and Oath of the five, they set forth their Standards against lord Thiye.

Now there standeth a Stone in the vale of Irien, Runecarven, which is like to the standing stones in Aenor and Sith and much like to the great Span of the Witchfire in Ivrel, by general report, and it was always avoided, howbeit no great harm had come therefrom.

To this place the lords of Andur rallied behind Tiffwy Han's-son and the Five, to make assault on Ivrel and Hjemur-keep. Then it became full clear that Tiffwy had been deceived by the Strangers, for ten thousands rode down Grioen's Height into the vale of Irien at the foot of Ivrel, and of them all perished, save one youth from Baien-an, hight Tem Reth, whose mount fell in the course and so saved his life. When he woke from his swoon there was nothing living upon the field of Irien, neither man nor beast, and yet no Enemy had possessed the field. Of the ten thousands there remained but few Corpses, and upon them there was no Wounding found. This Reth of Baien-an did quit the field alive, but much grieving on this account did enter into the Monastery of Baien-an, and spent his days at Prayers.

Having accomplished such Evil the Strangers vanished. It was widely reported however by the folk in Aenor that the Woman returned there, and fled in terror when they sought arms against her. By them it is given that she perished upon a hill of Stones, by them hight Morgaine's Tomb, for by4

Gate of Ivrel

this name she was known in Aenor-Pyvvn, though it is reported that she had many Names, and bore lord-right and titles. Here it is said she sleeps, waiting until the great Curse be broken and free her. Therefore each Yeare the folk of the village of Reomel bring Giftes and bind great Curses there also, lest perchance she wake and do them ill.

Of the Others, there was no trace found, neither at Irien nor in Aenor.

—Annals of Baien-an

5

Gate of Ivrel

Chapter 1

To be born Kurshin or Andurin was a circumstance that mattered little in terms of pride. It only marked a man as a man, and not a savage, such as lay to the south of Andur-Kursh in Lun; nor tainted with witchery and qujalinblood, such as the folk of Hjemur and northward. Between Andur of the forests and Kursh of the mountains was little cause of rivalry; it was only to say that one was hunter or herder, but both were true men and godly men, and once– in the days of the High Kings of Koris– one nation.

To be born of a particular canton, like Morija or Baien or Aenor– this was a matter that deserved loyalty, a loyalty held in common with all Morijin or Baienen or Aenorin of whatever rank, and there was fierce love of home in the folk of Andur-Kursh.

But within each separate canton there were the clans, and the clans were the true focus of love and pride and loyalty. In most cantons several ruling clans rose and fell in continual cycles of rivalry and strivings for power; and there were the more numerous lesser clans, which were accustomed to obey. Morija was unique in that it had but one ruling clan and all five others were subject. Originally there had been the Yla and Nhi, but the Yla had perished to the last man at Irien a hundred years past, so now there remained only the Nhi.

Vanye was Nhi. This was to say that he was honorable to the point of obsession; he was a splendid and brilliant warrior, skilled with horses. He was however of a quicksilver disposition and had a recklessness that bordered on the suicidal. He was also stubborn and independent, a trait that kept the Nhi clan in a constant ferment of plottings and betrayals.

Vanye did not doubt these truths about himself: this was after all the well-known character of the whole Nhi clan. It was expected of all who carried the blood, as each clan had its attributed personality. A Nhi youth spent all his energies either living up to expectations or living in defiance of his less desirable traits.

His half-brothers possessed these attributes too, as of course did lord Nhi Rijan, who was father to the lot of them. But Vanye was Chya on his 6

Gate of Ivrel

Korish mother's side; and Chya were volatile and artistic, and pride often ruled their good sense. His half-brothers were Myya, which was a Morij warrior-clan, subject, but ambitious, and its folk were secretive and cold and sometimes cruel. It was in Vanye's nature to be reckless and outspoken as it was in the nature of his two half-brothers to keep their own counsel. It was in his nature to be rash, while it was in that of his brothers to be unforgiving. It was no one's fault, unless it was that of Nhi Rijan, who had been reckless enough to beget a bastard Chya and two legitimate Nhi-Myya and to house all three sons under one roof.

And upon an autumn day in the twenty-third year of Nhi Rijan in Ra-morij, a son of Rijan died.

Vanye would not go into the presence of Nhi Rijan his father: it needed several of the Myya to force him into that torchlit room, which reeked so strongly of fire and fear. Then he would not look his father in the eyes, but fell on his face on the floor, and touched his brow to the cold stone paving and rested there unmoving while Rijan attended to his surviving heir. Nhi Erij was sorely hurt: the keen longsword had nearly severed the fingers of his right hand, his swordhand, and sweating priests and old San Romen labored with the moaning prince, giving him drafts and poultices to ease his agony while they tried to save the damaged members.

Nhi Kandrys had not been so fortunate. His body, brows bound with the red cord to tie his soul within until the funeral, rested between death-lights upon another bench in the armory.

Erij stifled a scream at the touch and hiss of iron, and Vanye flinched.

There was a stench of burned flesh. Eventually Erij's moans grew softer as the drugged wine had effect. Vanye lifted his head, fearing this brother dead also– some died under the cautery, of the shock, and the drugged wine together. But his half-brother yet breathed.

And Nhi Rijan struck with all the force of his arm, and cast Vanye sprawling and dazed, his head still ringing as he crawled to resume his kneeling posture, head down at his father's feet.

7

Gate of Ivrel

"Chya murderer," his father said. "My curse, my curse on you." And his father wept. This hurt Vanye more than the blow. He looked up and saw a look of utter revulsion. He had never known Nhi Rijan could weep.

"If I had put an hour's thought into your begetting, bastard son, I would have gotten no sons on a Chya. Chya and Nhi are an unlucky mixing. I wish I had exercised more prudence."

"I defended myself," Vanye protested from bruised lips. "Kandrys meant to draw blood– see—" And he showed his side, where the light practice armor was rent, and blood flowed. But his father turned his face from that.

"Kandrys was my eldest," his father said, "and you were the merest night's amusement. I have paid dearly for that night. But I took you into the house. I owed your mother that, since she had the ill luck to die bearing you. You were death to her too. I should have realized that you are cursed that way. Kandrys dead, Erij maimed– all for the likes of you, bastard son. Did you hope to be heir to Nhi if they were both dead? Was that it?"

"Father," Vanye wept, "they meant to kill me."

"No. To put that arrogance of yours in its place– that, maybe. But not to kill you. No. You are the one who killed. You murdered. You turned edge on your brothers in practice, and Erij not even armed. The fact is that you are alive and my eldest son is not, and I would it were the other way around, Chya bastard. I should never have taken you in. Never."

"Father," he cried, and the back of Nhi Rijan's hand smashed the word from his mouth and left him wiping blood from his lips. Vanye bowed down again and wept.

"What shall I do with you?" asked Rijan at last.

"I do not know," said Vanye.

"A man carries his own honor. He knows."

8

Gate of Ivrel

Vanye looked up, sick and shaking. He could not speak in answer to that.

To fall upon his own blade and die– this, his father asked of him. Love and hate were so confounded in him that he felt rent in two, and tears blinded him, making him more ashamed.

"Will you use it?" asked Rijan.

It was Nhi honor. But the Chya blood was strong in him too, and the Chya loved life too well.

The silence weighed upon the air.

"Nhi cannot kill Nhi," said Rijan at last. "You will leave us, then."

"I had no wish to kill him."

"You are skilled. It is clear that your hand is more honest than your mouth.

You struck to kill. Your brother is dead. You meant to kill both brothers, and Erij was not even armed. You can give me no other answer. You will become ilin.This I set on you."

"Yes, sir," said Vanye, touching brow to the floor, and there was the taste of ashes in his mouth. There was only short prospect for a masterless ilin,and such men often became mere bandits, and ended badly.

"You are skilled," said his father again. "It is most likely that you will find place in Aenor, since a Chya woman is wife to the Ris in Aenor-Pyvvn.

But there is lord Gervaine's land to cross, among the Myya. If Myya Gervaine kills you, your brother will be avenged, and it will be without blood on Nhi hands or Nhi steel."

"Do you wish that?" asked Vanye.

"You have chosen to live," said his father. And from Vanye's own belt he took the Honor blade that was the peculiar distinction of the uyin,and he seized Vanye's long hair that was the mark of Nhi manhood, and sheared it off roughly in irregular lengths. The hair, Chya and fairer than was thought honest human blood among most clans, fell to the stone floor in its 9

Gate of Ivrel

several braids; and when it was done, Nhi Rijan set his heel on the blade and broke it, casting the pieces into Vanye's lap.

"Mend that," said Nhi Rijan, "if you can."

The wind cold upon his shorn neck, Vanye found the strength to rise; and his numb fingers still held the halves of the shortsword. "Shall I have horse and arms?" he asked, by no means sure of that, but without them he would surely die.

"Take all that is yours," said the Nhi. "Clan Nhi wants to forget you. If you are caught within our borders you will die as a stranger and an enemy."

Vanye bowed, turned and left.

"Coward," his father's voice shouted after him, reminding him of the unsatisfied honor of the Nhi, which demanded his death; and now he wished earnestly to die, but it was no longer help for his personal dishonor. He was marked like a felon for hanging, like the lowest of criminals: exile had not demanded this further punishment– it was lord Nhi Rijan's own justice, for the Nhi had also a darker nature, which was implacable and excessive in revenge.

He put on his armor, hiding the shame of his head under a leather coif and a peaked helm, and bound about the helm the white scarf of the ilin,wandering warrior, to be claimed by whatever lord chose to grant him hearth-right.

Ilininwere often criminals, or clanless, or unclaimed bastards, and some religious men doing penance for some particular sin, bound in virtual slavery according to the soul-binding law of the ilincodes, to serve for a year at their Claiming.

Not a few turned mercenary, taking pay, losing uyinrank; or, in outright dishonor, became thieves; or, if honest and honorable, starved, or were robbed and murdered, either by outlaws or by hedge-lords that took their service and then laid claim to all that they had.

10

Gate of Ivrel

The Middle Realms were not at peace: they had not been at peace since Irien and the generation before; but neither were there great wars, such as could make an ilin's life profitable. There was only grinding poverty for midlands villages, and in Koris, the evil of Hjemur's minions– dark sorceries and outlaw lords much worse than the outlaws of the high mountains.

And there was lord Myya Gervaine's small land of Morij Erd which barred his way to Aenor and separated him from his only hope of safety.

* * *

It was the second winter, the cold of the high passes of the mountains, and a dead horse that finally drove him to the desperate step of trying to cross the lands of Gervaine.

A black Myya arrow had felled his gelding, poor Mai, that had been his mount since he first reached manhood; and Mai's gear now was on a bay mare he had of the Myya– the owner being beyond need for her.

They had harried him from Luo to Ethrith-mri, and only once had he turned to fight. Hill by hill they had forced him against the mountains of the south. He ran willingly now, though he was faint with hunger and there was scant grain left for his horse. Aenor was just across the next ridges. The Myya were no friends of the Ris in Aenor-Pyvvn, and would not risk his land.

It was late that he realized the nature of the road he had begun to travel, that it was the old qujalinroad and not the one he sought. Occasional paving rang under the bay mare's hooves. Occasional stones thrust up by the roadside and he began to fear indeed that it led to the dead places, the cursed grounds. Snow fell for a time, whiting everything out-stopping pursuit (he hoped that, at least). And he spent the night in the saddle, daring only to sleep a time in the early morning, after the movings in the brush were silenced and he no longer feared wolves.

Then he rode the long day down from the Aenish side of the pass, weak and sick with hunger.

11

Gate of Ivrel

He found himself entering a valley of standing stones.

There was no longer doubt that qujalinhands had reared such monoliths.

It was Morgaine's vale: he knew it now, of the songs and of evil rumor. It was a place no man of Kursh or Andur would have traveled with a light heart at noontide, and the sun was sinking quickly toward dark, with another bank of cloud rolling in off the ridge of the mountains at his back.

He dared look up between the pillars that crowned the conical hill called Morgaine's Tomb, and the declining sun shimmered there like a butterfly caught in a web, all torn and fluttering. It was the effect of Witchfires, like the great Witch-fire on Mount Ivrel where the Hjemur-lord ruled, proving qujalinpowers were not entirely faded there or here.

Vanye wrapped his tattered cloak about his mailed shoulders and put the exhausted horse to a quicker pace, past the tangle of unhallowed stones at the base of the hill. The fair-haired witch had shaken all Andur-Kursh in war, cast half the Middle Realms into the lap of Thiye Thiye's-son. Here the air was still uneasy, whether with the power of the Stones or with the memory of Morgaine, it was uncertain.

When Thiye ruled in Hjemur

came strangers riding there,

and three were dark and one was gold,

and one like frost was fair.

The mare's hooves upon the crusted snow echoed the old verses in his mind, an ill song for the place and the hour. For many years after the world had seen the welcome last of Morgaine Frosthair, demented men claimed to have seen her, while others said that she slept, waiting to draw a new generation of men to their ruin, as she had ruined Andur once at Irien.

Fair was she, and fatal as fair,

and cursed who gave her ear;

now men are few and wolves are more,

and the Winter drawing near.

12

Gate of Ivrel

If in fact the mound did hold Morgaine's bones, it was fitting burial for one of her old, inhuman blood. Even the trees hereabouts grew crooked: so did they wherever there were Stones of Power, as though even the nature of the patient trees was warped by the near presence of the Stones; like souls twisted and stunted by living in the continual presence of evil. The top of the hill was barren: no trees grew there at all.

He was glad when he had passed the narrow stream-channel between the hills and left the vicinity of the Stones. And suddenly he had before him a sign that he had run into better fortunes, and that heaven and the land of his cousins of Aenor-Pyvvn promised him safety.

A small band of deer wandered belly-deep in the snows by the little brook, hungrily stripping the red howanberries from the thicket.

It was a land blessedly unlike that of the harsh Cedur Maje, or Gervaine's Morij Erd, where even the wolves often went hungry, for Aenor-Pyvvn lay far southward from Hjemur, still untouched by the troubles that had so long lain over the Middle Realms.

He feverishly unslung his bow and strung it, his hands shaking with weakness, and he launched one of the gray-feathered Nhi shafts at the nearest buck. But the mare chose that moment to shift weight, and he cursed in frustration and aching hunger: the shaft sped amiss and hit the buck in the flank, scattered the others.

The wounded buck lunged and stumbled and began to run, crazed with pain and splashing the white snow with great gouts of blood. Vanye had no time for a second arrow. It ran back into Morgaine's valley, and there he would not follow it. He saw it climb– insane, as if the queerness in that valley had taken its fear-hazed wits and driven it against nature, killing itself in its exertions, driving it toward that shimmering web which even insects and growing things avoided.

It struck between the pillars and vanished.

So did the tracks and the blood.

The deer grazed, on the other side of the stream.

13

Gate of Ivrel

He gazed at the valley of the Stones, where there was no doubt that qujalinhands had reared such monoliths. It was Morgaine's vale: he knew it. The sight stirred something, a sense of déjà-vuso strong it dazed him for a moment, and he passed the back of his hand over his eyes, rubbing things into focus. The sun was sinking quickly toward dark, with another bank of cloud rolling in off the ridge of the mountains, shadowing most of the sky at his back.

He looked up between the pillars that crowned the conical hill called Morgaine's Tomb, and the declining sun shimmered there like a puddle of gold just disturbed by a plunging stone.

In that shimmer appeared the head of a horse, and its fore-quarters, and a rider, and the whole animal: white rider on a gray horse, and the whole was limned against the brilliant amber sun so that he blinked and rubbed his eyes.

The rider descended the snowy hill into the shadows across his path—substantial. A pelt of white anomenwas the cloak, and the stranger's breath and that of the gray horse made puffs on the frosty air.

He knew that he should set spurs to the mare, yet he felt curiously numb, as though he had been wakened from one dream and plunged into the midst of another.

He looked into the tanned woman's face within the fur hood and met hair and brows like the winter sun at noon, and eyes as gray as the clouds in the east.

"Good day," she gave him, in a quaint and gentle accent, and he saw that beneath her knee upon the gray's saddle was a great blade with a golden hilt in the fashion of a dragon, and that it was Korish-work upon her horse's gear. He was sure then, for such details were in the songs they sang of her and in the book of Yla.

"My way lies north," she said in that low, accented voice. "Thee seems to go otherwise. But the sun is setting soon. I will ride with thee a ways."

14

Gate of Ivrel

"I know you," he said then.

The pale brows lifted. "Has thee come hunting me?"

"No," he said, and the ice crept downward from heart to belly so that he was no longer sure what words he answered, or why he answered at all.

"How is thee called?"

"Nhi Vanye, ep Morija."

"Vanye– no Morij name."

Old pride stung him. The name was Korish, mother's-clan, reminder of his illegitimacy. Then to speak or dispute with her at all seemed madness.

What he had seen happen upon the hilltop refused to take shape in his memory, and he began to insist to himself that the hunger that had made him weak had begun to twist his senses as well, and that he had encountered some strange high-clan woman upon the forsaken road, and that his weakness stole his senses and made him forget how she had come.

Yet however she had come, she was at least half– qujal,eyes and hair bore witness to that: she was qujaland soulless and well at home in this blighted place of dead trees and snow.

"I know a place," she said, "where the wind does not reach. Come."

She turned the gray's head toward the south, as he had been headed, so that he did not know where else to go. He went as in a dream. Dusk was gathering, hurried on by the veil of cloud that was rolling across the sky.

The wraithlike pallor of Morgaine drifted before him, but the gray's hooves cracked substantially into the crusted snow, leaving tracks.

They rounded the turning of the hill and startled a small band of deer that fed upon howanby the streamside. It was the first game he had seen in days. Despite his circumstance, he reached for his bow.

15

Gate of Ivrel

Before he could string it, a light blazed from Morgaine's outstretched hand and a buck fell dead. The others scattered.

Morgaine pointed to the hillside on their right. "There is a cave for shelter.

I have used it before. Take what venison we need: the rest is due smaller hunters."

She rode away upon the slope. He took his skinning-knife and prepared to do her bidding, though he liked it little. He found no wound upon the body, only a little blood from its nostrils to spot the snow, and all at once the red on the snow brought back the dream, and made him shiver. He had no stomach for a thing killed in such a way, and the wide-eyed horned head seemed as spellbound as he– unwilling dreamer too.