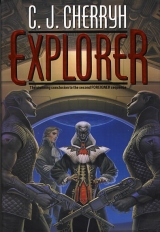

Текст книги "Explorer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

And somewhere in the hard-wiring of Prakuyo’s own massive body, this damnable elusive quantity was, clearly, so simple—if one were Prakuyo. If one’s brain had the sights and sounds and smells and emotional context of being Prakuyo. Which a human hadn’t, and wasn’t, by a long shot.

“We.” Prakuyo said that last in ship-speak. And pointed at him, and Banichi and Jago.

Wrong. That should be a you, and he opened his mouth to say so.

And shut it. Prakuyo looked—dared one think—quite earnest about that mistake.

Bren followed a gut instinct. Pointed to himself and Banichi and Jago. “We.” To himself and Prakuyo and Banichi and Jago. “We.”

Prakuyo got up quickly, making that alarmed booming sound. Banichi and Jago were on their feet just as fast.

But Prakuyo subsided back into his chair as if the air had been let out of him, and thrummed and boomed and clenched his hands together in front of his mouth—not pleased. Or at least—not feeling particularly stable at the moment.

And at a loss for words.

“ Not we?” Bren pushed the point.

He won a dark-eyed, distraught look.

Banichi and Jago sat back down, stoic and impeccable.

“We.” That word again, indicating him, Banichi and Jago, but not including Prakuyo.

Don’t include me. Don’t assimilate me. Don’t absorb me.

We—some quality of we—was as disturbing to Prakuyo as it was ordinary and all but invisible to humans and atevi. But not a take-for-granted among atevi; and not, even in his lifetime, an easy given between humans and atevi. A fogged brain began to gather, beyond the obvious answer of a xenophobia Prakuyo never had demonstrated, that he simply had no wish to be included, and did not give his consent to be included. That somehow, with him and with his kind, we was a fenced-off, difficult word that might imply anything from visceral distaste to outright hatred of outsiders—no evidence in Prakuyo for that; though that hole in the station might attest differently.

What was behind that reaction? Prakuyo’s wrist was as large as a human upper arm. Strength, immense strength: this wasn’t a species that, in its evolution, easily hid or ran; it might, perhaps, take direct solutions; but with complementary delicacy, these hands had built spaceships. Prakuyo’s kind must have made pots, learned agriculture, domesticated animals, made villages, made towns, made cities, made whatever political structures let Prakuyo’s kind cooperate and launch itself into space.

But Prakuyo’s people had trouble including other species with itself.

Or Prakuyo had trouble being included by others, or by them, specifically.

Politics? Social structure? Something that disgusted or frightened?

Prakuyo, however, was willing to sublimate that feeling enough to talk, to learn, even to express enjoyment.

And suddenly something reverberated through the hull, a deep, distant shock. Banichi and Jago both got up, and Banichi left them.

A shot? Bren wondered with a chill. Hostilities with the station, or had that ship out there moved in and simply decided to blow its own way into the hull?

Was all time up?

Prakuyo was incapable of looking worried, in human terms, but he looked at the door, looked about him, the same.

“Hear,” Bren acknowledged the event. He had not yet gotten words for know and not know , was unsure of those pesky soft-tissue conditionals if and then . His attempt to extract them with a flow chart had produced uncertain results—which, along with the absence of pronouns, could mean bad news. A set of conditionals that didn’t jibe with Mosphei’, which was relatively simple, nor Ragi, which wasn’t simple at all. If that was an explosion, nadiin, then we have a problem…

He was losing his focus, getting wobbly.

“Nandi,” Jago said, from the doorway, and he looked at her. “Jase reports that the alien craft has arrived and established a connection.”

Adrenalin ran like static through nerves already on overload.

Then the habits of the aiji’s court came to the rescue, providing stability for a small bow, an utter microfocus on the Prakuyo matter.“Prakuyo ship, Prakuyo-ji. It has come. Go up.”

Prakuyo absorbed that information and solemnly rose. Bren started for the door, then remembered the notes, frantically gathered them up and gave them to Jago as they reached the door. “These must get to Jase. To C2.”

“Yes,” Jago said.

As their party ran up against the resident seven-year-old, rigged out in lace and red and black brocade, and behind Cajeiri his great-grandmother, in much the same, with gold; and behind the dowager, Cenedi and reinforcements.

The dowager didn’t move that fast. Someone had been in close touch with Jase while he had been locked in the throes of new vocabulary.

“This has gone on long enough,” Ilisidi said, and banged her cane against the deck. “We have our invitation, one supposes, since the ship has complied with Jase-aiji’s instruction. Prakuyo-ji, we shall see this ship of yours and settle this business.”

Prakuyo bowed, deeply, even gracefully. The change in dress had provoked no comment—of course the staff had come up with something suitable: the dowager expected such miracles, and was prepared to lead the way.

“My best car,” Cajeiri said, holding it safely in his arms. A bow. Very best behavior, as well.

Banichi came out of the security station and quietly waited for them.

A second stamp of the dowager’s cane, a motion down the corridor toward the door. “Well,” she said. “Shall we dither here, or have this business on the road?”

“Nandi,” Bren murmured, and drew a deep breath, and fell in with her, and with Prakuyo, Cajeiri closing up ranks and staying rather closer to his great-grandmother—not a swift progress: not in the dowager’s company, but steady. They gathered up Banichi by the security station, and how the papers got passed, or what arrangements flew in a handful of words between Jago and Asicho, he had no idea, but he trusted the ship would ultimately have diagrams if he needed them.

The guards at the farthest doors opened them, and they walked to the lift and requested a car. Bren drew out his pocket com and requested through to Jase during the wait.

“Jase,” he said, “I understand we’ve got a connection to the ship. We’re on our way. Looking reasonably good. Got some graphics coming up to you.”

“ We’ll handle it ,” Jase said. “ Bren. Bren, take very good care. I wish I was backing you .”

“You are,” Bren said. “No question. Our car’s coming. Which lock?”

“ Number 3. That’s 243 on the pad. We’re watching you, far as we can. Good luck .”

“Good luck to all of us. Back in a few hours. Or not. If not, don’t do anything. Let me work it out. I’ll do it.”

“ I trust you ,” Jase said; and the lift door opened. “ A few hours .”

The last in Ragi. End of the conversation. He thumbed the unit off as he escorted the dowager and Prakuyo through the doors. Cajeiri next. Their bodyguard. He cast a look at Banichi, looking for signs of wear, and found none evident.

He couldn’t afford to divert his attention. Made up his mind not to. He wondered if he should have brought a heavy coat. Then recalled that Prakuyo was quite comfortable in five-deck temperatures.

Prakuyo, at the moment, looked from the doors to them and back again, agitated, anxious—dared one say, joyous? One certainly hoped so.

Long, long ride.

“How far up—” Cajeiri began to ask, and the dowager’s cane hit the decking. Young arms clenched the car close; young head bowed. “One forgot, mani-ma.”

“Then one’s attention was not on one’s instructions. This will be a strange place, and no questions. Think matters through, young sir.”

One did not answer the boy’s question, no matter how tempted, in the face of the dowager’s reprimand.

One simply took that advice for oneself. A strange place, and no questions, indeed. No ability to ask. No words.

But hope. There was that.

The car slowed. The illusion of gravity slowly left them. Bren found his heart pounding and his hands sweating, a fact he chose not to make evident. Cajeiri, who had seen zero-g, restrained himself admirably.

Bren doggedly smiled at Prakuyo drifting next to him, at Banichi and Jago who, one noted, wore no visible armament, no more than the dowager’s guard—a peace delegation, Ragi-style; but he wasn’t sure they’d pass a security scan. Which was Ragi-style, too.

Doors opened. A handful of Phoenix crewmen met them, drifting near the doors. They had sidearms, but nothing ostentatious. They were there to operate the locks for them and to sound an alarm, one suspected, if anything went massively wrong.

“Good luck, sir. Ma’am. Sir.” The last, dubiously, toward Prakuyo. With a bow. Ship’s crew had learned such manners with the atevi.

“Good,” Prakuyo rumbled, as they drifted into the chamber, breaths frosting into little clouds.

Machinery worked and the doors behind them hissed and sealed, ominous sound. No panic, Bren said to himself, thinking strangely of the hiss of the surf on the North Shore. Sunset. Sea wind.

Pumps worked only a moment; and the doors unsealed facing them.

The air that met them made an ice film on every surface, stung the fingers. Prakuyo bounded along, catching handgrips, and the dowager simply allowed Cenedi to draw her along, while Cajeiri was quite content to help himself. Bren managed, teeth chattering, wishing there were a conveyor line.

Long, long progress, and one had the overwhelming feeling of being watched throughout, watched, analyzed for weakness, and the human in the party was determined not to show how very fast he chilled through.

They were arriving, finally, at an end, a chamber with a metal grid, and Prakuyo entered it cheerfully, beckoned them in and showed them to hold on.

Good idea. Doors banged shut, the whole affair began to move and spun about violently, under unpleasantly heavy acceleration to give them a floor, after which the air that came wafting from the vents came thick as a swamp, still freezing where it hit metal and condensed.

Rough braking. Cenedi supported the dowager, Cajeiri had to catch himself, and Bren just held on.

They weighed too much. The air was thick as a swamp at midnight. Doors whined and banged open on a dim, dank place, dark blue-green floor, dark greenish blue walls intermittent with deeper shadow—a succession of edge-on panels, the light so dim it fooled the eye.

A deep rumbling came from all around, and what might be words. Prakuyo bowed deeply, walked forward a step, and out of the shadows a distance removed appeared a solitary, cloaked figure, with Prakuyo’s face, and Prakuyo’s bulk.

“Stop here,” Ilisidi advised, and the paidhi thoroughly agreed: no one should go further, but Prakuyo, who walked a few paces on, bowed again.

Said a handful of words, it might be, underlain with thrumming and booming.

Stark silence from the other side. And as silently—more cloaked individuals from behind the standing panels, and more voices, more booming and rumbling until the floor seemed to vibrate.

Not good, Bren thought, standing very still, not good if Prakuyo left them. It was not a comfortable place, even to stand. He felt as if he’d gained fifty pounds. The dowager’s joints would by no means take this kindly.

But Prakuyo extended an arm toward them—beckoning, one thought. “Dowager-ji,” Bren said quietly, and moved forward a little. And bowed, as Prakuyo had. One trusted the dowager gave a slight courtesy. Their bodyguards, by custom, would not, until the situation was certain.

“Introduce us,” the dowager said, “paidhi-aiji.”

“Indeed,” Bren said. He walked forward a step, and bowed, trying to assemble recently gained words. “Bren,” he said, laying a hand on his chest. “From human and atevi ship. Good stand here.”

One hoped not to have made a vocabulary mistake. An immediate murmur went through the gathering, a visible shifting of stance.

“Ilisidi, ateva, comes, says good on Prakuyo ship.”

Ilisidi walked forward a pace, bringing Cajeiri with her, offering a little nod. Cajeiri, wide-eyed, made a little bow of his own, car clutched firmly against his ribs, and wisely kept very quiet.

Prakuyo, however, had a deal to say. He waved an arm and talked—one could pick out words—about the station, about going to the ship, about them, by name and individually: he talked passionately, thrumming softly under his breath, and walked from this side to the other, finally demonstrating his own person.

“Bren,” Prakuyo said then. “Come. Come talk. Say.”

Bren drew a breath, walked to Prakuyo’s side, and gave another bow to the one who had appeared first, the one Prakuyo had addressed. “Bren Cameron,” he said, a hand on himself.

“Good Prakuyo on Prakuyo ship.” Never using that chancy we . Never having found Prakuyo’s word for the same. “Bren, Ilisidi take humans from station to ship. Ship goes far, far. No fight.”

That other person spoke, not two words intelligible, and not thoroughly warm and welcoming, either.

Prakuyo clapped a heavy hand on Bren’s shoulder, a comfort, considering the ominous murmur around about; and Prakuyo talked rapidly—shocking his hearers, to judge by the reaction.

“Calm,” Bren said in Ragi. “One asks helpful calm.”

“Calm,” Prakuyo agreed—knowing that word, it turned out. And launched on an oration in his own language, his one hand holding Bren steady, his word-choice something about station and Madison, quite angrily—then something about Ilisidi, and Bren, about Bindanda—perhaps about teacakes, for all Bren could tell, and a torrent besides that.

There was an argument, a clear argument going on.

And one had to think that for well over six years neither humans nor Prakuyo’s species had made sense to each other, and that the reason they were all standing here in this fix might well have had to do with a now-deceased captain poking about in solar neighborhoods that weren’t his—it wasn’t just Prakuyo’s grievance; it was likely a number of Prakuyo’s people with complaints about the goings-on.

Prakuyo, however, let him go, and engaged in noisy argument with several others. Bren tried to decide whether it was prudent to get out of the way; but then Ilisidi moved, slowly, considerately, with Cajeiri, and Banichi and Jago found opportunity to move up into his vicinity: but a person used to the Assassins’ Guild noted Cenedi had not moved with the group—Cenedi had stayed back there with his partner, nearer the door, and most certainly was armed.

“Not come fight,” Bren interjected into Prakuyo’s argument, seeing tension rising on this side and that, and at a light tap of the dowager’s cane, wanting his attention, interposed a translation. “Dowager-ma, I am attempting to assert our benevolent intentions. They are discussing what happened here. Prakuyo-nadi seems to be taking a favorable position. But we have no idea what Ramirez-aiji may have done to provoke this: I am suspicious he, rather than the station, triggered hostilities.”

“Pish.” A wave of the hand. “One cares very little what they and humans did.” Bang went the cane. “Now we are annoyed, and we wish a sensible cessation.”

There was a moment’s startled silence. Prakuyo said something involving Ilisidi, and Cajeiri, and something Bren couldn’t remotely follow—a rapidfire something that brought a closer general attention on Ilisidi and the boy.

Then came what might questions from the senior personage, involving Ilisidi and the boy. And him. And Banichi and Jago. They were short of vocabulary and on very, very dangerous ground, and the argument concerning them was getting altogether past them. Not good.

“Nand’ Prakuyo.” Respectfully, since Prakuyo was clearly a person able to give and take with the leadership of this vessel. “Say to this person that humans and atevi go away. Not want to fight. Want to go soon,”

“We,” Prakuyo said, and said a word of his own language, indicating himself and all the others. Then that same word including Bren and Ilisidi and all the rest. And something more complicated, more emphatic, that provoked strong reaction, dismay.

Damn, Bren thought, wondering what that past argument about we and they might have produced here. Prakuyo’s folk didn’t like that word. Passionately didn’t want to be lumped together with non-whatever-they-were. Prakuyo hadn’t been for it, either.

But Prakuyo argued with the idea now. Argued, with occasional booms from deep in his chest that sounded more deeply angry than mournful. And finally gave a wave of his hand, ending argument, producing some instruction to the onlookers.

“Drink,” Prakuyo said, “come drink.”

Was that the resolution? An offering so deep in the roots of civilized basics it resonated across species lines?

“Nandi,” he said to Ilisidi, “we are possibly offered refreshment, which in my best judgment would not be wise to refuse.”

“About time,” Ilisidi said, hands braced on her cane. “Great-grandson?”

“Mani-ma.”

“We shall see the most correct, the most elegant behavior. Shall we not?”

“Yes, mani-ma.”

“Come,” Prakuyo said to them, “come.”

“Cenedi,” Ilisidi said, and their rear guard quietly added themselves back to the party as they walked slowly with Prakuyo, between two of the edge-on panels, into deep shadow that gave way to a broad corridor, with adjacent panels sharply slanted, obscuring whatever lay inside.

Two such moved, affording access to a room of cushioned benches of atevi scale, and Prakuyo himself came and offered his hand to Ilisidi, whose face was drawn with the effort of moving in this place.

It wasn’t court protocol. It was, however, courtesy, and sensible in this place of dim light, uncertain footing, and exhausting weight: Ilisidi allowed herself to be seated, patted the place beside her for Cajeiri, and on her other side, for Bren.

Prakuyo also sat down, with that other individual, who proved, in better light, to be an older, heavier type, with numerous folds of prosperous fat.

Younger persons brought a tray with a medium-sized pitcher and a set of cups—one would expect tea, and a human experienced in atevi notions of tea worried about alkaloids; but what the young persons poured for them proved to be water, pure, clean water.

“Very good,” Ilisidi remarked, which Prakuyo translated; and himself poured more for her and for the rest of them.

“Good,” Prakuyo said. “Good come here.” He said something more to the older person, and by now others had come in to observe, and to listen to Prakuyo’s account, which ranged much farther than Bren could follow.

It took the tone, however, of a storyteller getting the most out of the situation, and came down to mention of their names again, and expansive gestures that looked unpleasantly like explosions.

“Ilisidi,” Prakuyo said then. “Say.”

“We have come,” Ilisidi said, paying no attention to this gross breach of courtly protocols, “we have come to settle matters, to recover these ill-placed humans and take them away, where they will cause you no further trouble. The ship-aiji who caused these difficulties is dead. The station-aiji who treated you badly is deposed and will never have power again, and the ship-aiji who rescued you is now in charge of the ship and the station. We take no responsibility for the doings of these foreign humans but we are glad to have returned you to your ship.”

Prakuyo launched into God-knew-how-accurate a translation, or explanation, or simply an elaboration of his prior arguments. At which point he asked for something, and one of the lesser persons ran off, presumably on that errand.

Prakuyo kept talking, overwhelming all argument, dominating the gathering. Clearly, Bren thought, this was not a common person, though what the hierarchy was on this ship was not readily clear. Six years they’d sat watching, observing—by all evidence of the damage done to the station, capable of simply taking it out, and of having done so before Prakuyo ever came close enough to get himself in trouble. But they’d taken a twofold approach: first to send in a living observer, then to sit and wait—long on a human timescale—six years.

For what? For Prakuyo to teach the humans to talk to them? For the ship that had left to come back? They hadn’t hit it, either, but they might well have tracked it.

A cautious folk. Capable of doing the damage they’d done—but they’d taken a long time to respond to Ramirez’s intrusion: they’d come in on the station rather than the mobile ship; they’d gotten provoked into a response, and then sat and watched the result. This wasn’t, one could think, a panicked, edge-of-capability sort of action, rather an action of someone as curious as hostile, wanting to know exactly how wide and fast the river was before they tried to swim in it.

The errand-runner came back with a tablet of opaque plastic and a marker, which Prakuyo took, and offered to Bren.

Communicate. Do the pictures. He obliged, and saw to his amazement that his very first mark appeared on a panel at the end of the room. He had an audience. He could start at the beginning. He could make them understand how the whole business had happened. Or he could try. Or he could just get to the point.

He drew a planet and a sun. “Earth,” he said. “Sun.” He drew a ship going out. “Ship. Human ship.” He shaded a dark spot along its route, drew many arrows going out, drew spirals and circles for the lost ship’s route. A dotted line. To a star. Solid line to another star. “Atevi earth. Human ship.”

Prakuyo elected to interpret—one only hoped he got it right; but Prakuyo had been locked into this limited vocabulary, part of the attempt to communicate.

“Human station. Atevi world. Human ship goes away. Humans go from station to atevi world.”

More translation.

“Humans, atevi on earth. Human, atevi, we. Ship they. Ship goes here, here, here. Ship makes station here. Ship goes here and here.” A complicated course, always centering on the second station. “Prakuyo ship comes to the human station, fight. Ship comes to station, comes to atevi world. Atevi and human, we come up to station, say to ship, you take humans from station, bring here to atevi and humans. Atevi and human we want no fight Prakuyo ship. Atevi and humans take Prakuyo on ship, take to Prakuyo ship. No fight.”

Again, a translation, vehement and excited. Prakuyo got up and demonstrated his atevi clothing, to the good, one thought: Prakuyo was not at all unhappy with his treatment on the ship.

It seemed an opportune moment, given the precedent of the water offering. Bren took his packet of fruit candies from his pocket and offered them to Prakuyo, who cheerfully took them, ripped the packet with a sharp tooth, and offered them about.

These were appreciated.

“Prakuyo-ji.” A young atevi voice, uncharacteristically muted. Cajeiri got up very carefully, and handed Prakuyo his car. “I brought it for you.”

Prakuyo took the offering, and took Cajeiri in a strong embrace, and talked with a great deal of booming and humming, even tugging Cajeiri’s pigtail, unthinkable familiarity, but Cajeiri was wise and held his peace.

Questions started. A lot of questions. And lengthy answers. Fruits appeared, on platters. It began to be a festivity, and if they could exit unpoisoned, Bren said to himself, they might secure the peace.

One tasted such things very gingerly. Only a taste. But that much surely was mandatory. There was a general easing of tension. More offering of water. Of little bits of bread and oil, which human taste found encouragingly safe-tasting.

“Good,” Prakuyo said with enthusiasm. “Good.” A powerful pat on the shoulder. “Bren take humans from station. Get all humans. Kyo take station.”

“Yes,” Bren said. Best they could get. They’d blown the archive. “Kyo good.”

“Human-atevi good.” Another blow to the shoulder. “Ilisidi go take Cajeiri. Go ship. Prakuyo come, go, come, go, more talk.”

Permission to go. Prakuyo would go with them and come and go at will. One could by no means ask better.

“One is grateful.” A bow. Perspiration glistened on Ilisidi’s brow. They had to get Ilisidi out of this heavy place. “Aiji-ma, we shall go back to the ship and continue negotiations.”

“Indeed,” Ilisidi said, and—Bren’s heart labored for her—rose, leaning on her cane. Cenedi moved to assist, but bang! went the cane on the floor, startling every person present except those who knew her. “We shall do very well for ourselves,” she said, and gave a polite, leisurely nod to Prakuyo. “We shall go to our ship. We shall have a decent rest. Then we shall be pleased to meet your delegation.”

“The dowager says good, talk soon,” Bren translated the intent into Prakuyo’s language, and bowed as the dowager turned, walking slowly. Cajeiri assisted her, providing his young arm under the guise of being shepherded along. Cenedi went close to her.

Prakuyo bowed during this retreat. Wonder of wonders, the rest bowed—perhaps grandmother translated very well, and found special resonance among the kyo.

Ilisidi seemed quite pleased with herself, standing square on her feet at the back of the airlock-combined-with-lift, as the rest of their party hastened aboard.

The door shut. The car started through its gyrations, and Ilisidi, off balance, had to accept Cenedi’s arm. And her great-grandson’s, on the other side.

“They seem perfectly civilized,” she said. “One can hardly see why we have had these difficulties.”

“Braddock-aiji,” Cajeiri said, having a bone-deep atevi understanding of how the intrigues lay.

The lift spun through its path and delivered them to the tube; and here, without gravity, Ilisidi let herself be moved gently along. Bren followed, glancing to be sure Banichi was all right: Jago was close by him, Cenedi’s men close behind.

They had done it. Bren allowed himself the dizzying thought. Prakuyo and he would talk, they would take their notebooks and their little dictionaries and make some sort of agreement.

They reached the frosted airlock, and locked through to the astonishing sight of an ordinary human face—several of them. Jase was one.

“Nandi.” Immediately Jase bowed to the dowager, who found it an opportune moment to sit down on the let-down seat at the guard post, her cane braced before her, her hands as pale as ever Bren had seen, and frost a gray sheen on her pepper-shot hair.

Cajeiri got down on his knee beside her and rubbed her arm. “It was very brave, mani-ma.”

“The dowager has gotten us an agreement,” Bren said quietly, to Jase, in Ragi. “Undefined, as yet, but expressions of willingness to talk.”

“Your job,” Jase said, laying a hand on his recently bruised shoulder. “You’ll do it. We’re still boarding passengers. We can do that and talk; and then we get to the fuel. Excellent job, nadi.”

“Hardly my doing.” He found himself wobbly in the knees and envied the dowager the seat, but would by no means dislodge her, or suggest they send for transport. “One believes the dowager will do very well with a little rest and warmth, Jase-ji. A little hot tea might come quite welcome.”

“A little less of talk,” Ilisidi said, and gained her feet, frightening them all. “The lift will get us home well enough. Jase-aiji, attend us down.”

Jase doubtless had a thousand things on his mind. But he had a key that preempted all other codes, and got them a lift car, despite the traffic that continually whined and thumped its way through the ship’s length.

The dowager walked in under her own power. Bren walked in, attended by the rest, all of them in one packet.

“Prakuyo will come back aboard to talk,” Bren said.

“Prakuyo.” Jase tried the name out.

“We think that’s his name. It could be his species.” So little they knew, at this point, about each other. Several things pleased the kyo about their expedition: the presence of an elder was one. Several things the kyo found shocking: the inclusion of themselves in the word we certainly seemed a matter of high debate.

But Prakuyo seemed about to make the jump.

Chapter 21

N ot much to report , brother, except ignore the last will and testament, which now seems embarrassing. We’ve loaded precisely 4043 persons and put their luggage through stringent checks for contraband, though what contraband one could find in this desolate station, I can’t imagine. Fruit sugar has produced a few stomach complaints, but the addiction is spreading. Likewise the taste for green plants. A few of the old people insist it gives them stomach ache, and they want their yeasts, but that’s only to be expected, I suppose .

I’ve met numerous times with Prakuyo and his association, there and here, during the last two days, and we’re more establishing vocabulary than conducting truly meaningful negotiations, but it’s pretty clear they’re to take over the station, which is not that far from places they consider theirs – more about that when I get back, when we can discuss this on a suitable beach .

Banichi took a little damage, which is mending nicely. Jago is coddling him shamelessly.

More later.

Aiji-ma, we are about to fuel the ship, and there will be no further difficulty. Gin-aiji has vouched for the machinery as of this morning.

A small note: Prakuyo-aiji indicates the observing ship was regularly receiving supply and exchanging information with others during the last six years, and that Ramirez-aiji had indeed encroached on places the kyo prefer to keep untraveled. The kyo attempt at approach apparently frightened Braddock, which ended in the kyo envoy being held these last six years. The kyo are very glad to know that responsible persons have shown up to rein in such adventures, so that kyo and atevi and humans may establish the nature and extent of their associations in reasonable security.

It should be noted that the kyo ship is very heavily armed, or at least was capable of extraordinary damage. I directly asked Prakuyo if he had knowledge of any other peoples beyond atevi and humans, and he seemed to say that such persons were not welcome in kyo territory. The kyo may be a barrier to such foreigners arriving in atevi regions, or they may have enmities of their own, a possibility which may indicate more caution in our relations with them. They do seem reasonable once approached at close range, but one cannot give credit enough to the aiji-dowager’s wise influence as an elder, which position they do greatly respect, and the fact that she could speak to them in a language recognizably not the language of humans who had offended against the kyo.