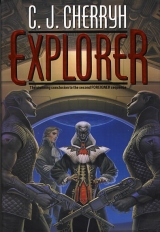

Текст книги "Explorer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Not alone now. In their own territory in the corridor, Asicho still dutifully sat the security station, never taking her attention from the situation, while Narani and Bindanda and Jeladi had all turned out to welcome them, to open the door to his personal quarters.

“No time for rest, Rani-ji,” he said on the way through the door. “We have a situation, a successful docking on the one hand, but a very troublesome local authority. Sabin-aiji has gone ashore with ship security, ostensibly to try to deal with them, but rejecting advice. I shall need island clothes, Rani-ji, immediately without fuss, before some situation shuts down the lift system.”

“Nandi.” Narani asked no questions. The clothes would appear, with his staff’s fastest cooperation. Doubtless, too, the dowager and Cenedi were entering on much the same endeavor, down the hall, explaining to staff and laying plans of their own, which he hoped didn’t involve armed incursion into the maintenance passages.

But if the Pilots’ Guild should believe it could make a move on Jase and control the ship, he was very sure the dowager would move very quickly—benignly toward the crew, so be it, but all the same, no question but that Ilisidi would take all security, all decisions, all mission direction into her own hands. Ilisidi, absent Sabin, now saw no one to stop her, no one with whom to negotiate territories directly—and what came next was as basic as gravity, as fundamental as the history of the atevi associations: a power vacuum did not last, among atevi, not ten minutes. Atevi wars most often happened by accident, when signals were not quite clear and contenders for a vacancy jammed up in a figurative doorway.

Which meant signals were already flying, humans all oblivious to the fact. Unless Jase took a strong enough stand to stand Ilisidi off in Sabin’s name—it would happen. And that meant there was a very dangerous imbalance of powers developing, if he didn’t get himself up there and plant himself in a position to maintain that balance between Ilisidi, the Guild, and ship’s authority.

And what would the Guild do if the ship they relied on as their heritage, their only lifeline to the universe, their protection and refuge, suddenly turned out to be in alien hands?

And what would Phoenix crew do, if atevi, threatening all those traditions, moved suddenly against the Guild—which the crew increasingly didn’t like?

Those last two in particular were questions he hoped not to have to answer before the hour was out.

He was exhausted despite his few hours of sleep. He wanted nothing right now more than a bed to fall into.

But he did a quick change into a blue sweater and a pair of matching blue pants little distinguishable from the crew’s ordinary fatigues.

The hair—well, that was a problem. He thought even of cutting it off, though common crew had varying lengths—well, all shorter than his. But he had it in a simple pigtail, like Banichi’s or Jago’s, and made up his mind to brazen it out.

“A jacket, nandi?” Bindanda suggested. That had, he discovered, a pocket com. He shrugged it on over the pigtail and fended off Jeladi’s well-meaning attempt to extricate his hair.

Just as Narani offered him a small-for-atevi pistol, an assassin’s undercover weapon.

His own gun. After all these years—staff still had it oiled and ready.

“If necessary, nandi,” the old man said. “If one should in any wise need it on floors above.”

He hesitated. Thought no, of course not. Jase was in charge up there. He himself wasn’t a particularly good shot, nothing like his bodyguard. He was possibly more danger to their side with it than without it, relying on his wits.

And then he thought, dare I not? Dare I not go that far, if need be? If he had to take cover and got to the service accesses—what more argument, then? What far more drastic situation could develop up there, with Guild investigators coming aboard?

He took the pistol. Of course it was loaded—grandfatherly Narani, Assassins’ Guild himself, was certainly not shy of such things—and went out to the security station, where Banichi and Jago doublechecked a wire antenna imbedded in his collar.

“Be quite wary of transmission near these individuals that are coming aboard, Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “They may have means of noticing.”

“I have the gun,” he said, as if Banichi and Jago, in adjusting the connections, had possibly missed it. “I don’t at all think I shall at all need it, nadiin-ji, but one supposes better to have it and never need it.”

“Do use caution firing near conduits and pressure seals,” Jago said solemnly, and Banichi added:

“But do so if needful. Safety systems are generally adequate and quick. Look for a door you may shut if this fails.”

When had his security tested that theory?

“Keep the communications open,” Jago said from his left. “In the general activity all over the ship, a steady signal will be less notable than an intermittent one. Speak Mosphei’. That, too, will be less evident. We will take this ship, Bren-ji, at any moment your safety or liberty seems in question.”

“One will be very grateful at that point,” Bren said in a low voice. “But one fervently hopes no such event will happen, nadiin-ji.” Exhaustion had given way to a wobbly buzz of adventure. He was armed, wired, and on his own for the first time in—God, was it almost ten years?

He thought he could still manage on his own.

Chapter 10

A quick call on Ginny—that came first. And the simple act of getting into that section proved two reassuring points: that Jase had taken care of business and that their section doors were indeed not locked to their personal codes.

He surprised one of Gin’s men in the corridor. Tony, it was. Tony Calhoun, robotics.

“Mr. Cameron, sir.”

“Doors are set, autolock from the outside, protection against our station examiners prowling about, but codes still work on the pads. For God’s sake, don’t anyone walk out and forget your hand codes. Is Gin available?”

“Yes, sir. To you.” Tony thumped the door in question. Twice. Three times.

Gin answered the door in two towels. “Need help?”

“Just a heads-up. I’m up there to back Jase, if he needs it. You’re down here to back me, if you’ll do that—my staff’s monitoring. If they need a simple look-see topside, one of your people can go up, too, right?… Banichi may want to take action, but I’m sure he’ll appreciate an intermediate if he can get one. Meanwhile my staff may need a backup translator. Can you do it?”

“Best I can,” Gin said, holding fast to the primary towel. “Anything they need. Anything you need. Go. Get to it.”

The airlock started its cycle, distant thump. Someone was coming aboard or going out. They involuntarily looked up. Looked at each other.

“See you,” Bren said, and went back the half dozen steps down the hall and out to the lift, hoping that system still responded to his code, and hoping it picked up no other passengers.

It moved. He punched in, not the bridge, but up to crew level.

Deserted. Crew was still awaiting the next shift-change and nobody had gotten clearance to enter the corridors, not for food, not for any reason.

Secrets, they didn’t have on this voyage, not between captains and crew. But the lockdown had to chafe, and it couldn’t any longer be a question of crew safety, not with the ship linked to station.

Not a good situation. Not productive of good feelings aboard, granted there’d been one mutiny on this ship as was. And Jase hadn’t released them. Jase assuredly didn’t want common crew available for any Guild inspectors to interrogate. He could imagine the first question.

So where were you for the last nine years?

And the second.

What aliens?

Second cycling of the airlock. Bren found his heart beating faster, his footsteps a very lonely sound on two-deck.

Sabin was leaving with her guard, very, very likely, and not taking all the Guild intruders out with her. They couldn’t be so lucky as a quick formality and a release of prohibitions. The Guild inspectors were aboard now, he’d bet on it, as he’d bet that Sabin no longer was aboard and that the ship’s security had gone with her, leaving the techs, Jase, and that portion of the crew that routinely maintained, cleaned, serviced and did other things that didn’t involve armed resistence. They were, to all the Guild knew, stripped of defenses.

Sabin, however, wasn’t the only captain with a temper. Jase’s had been screwed down tight for the better part of a year—but it existed. Guild investigators, up there, were going to pounce on any excuse, question any anomaly; and if they found anything they were going to have their noses further and further into business.

While a captain who didn’t know the systems had to maintain his authority.

A decade ago, when Phoenix had come in here, had ordinary stationers rushed to board and take ship toward their best hope, the colony they’d left at Alpha? No. No more than common crew rushed into the corridors to do as they pleased. Spacers lived under tight discipline, and didn’t do as Mospheirans would do, didn’t go out on holiday when they’d had enough, didn’t quit their jobs or change their residence. They obeyed… except one notable time when the fourth captain, absent information, had raised a mutiny.

Guild leadership wanted Ramirez to take the ship out and reestablish contact with their long-abandoned colony. But fourth captain Pratap Tamun had taken a look at the situation of cooperation between Ramirez and the atevi world and raised a rebellion that, even in failure, had seeded uneasy questions throughout Phoenix crew.

Lonely sound of his own footsteps. Closed, obedient doors. Ask no questions, learn no lies.

And what else had Ramirez’s orders been when the Guild sent him on to Alpha?

And what did Sabin really understand about that last meeting between Ramirez and his Guild? And what did she intend to do, taking an armed force as her escort… some twenty men and women, her regular four, and Mr. Jenrette?

Among other points, Ramirez’s orders wouldn’t have Phoenix assume second place to the planet’s native governments, that was sure.

Not to take second place to the colonials supposedly running the station, also very sure.

To take over the colony that Reunion believed would be running the station, was his own suspicion of Ramirez’s intentions—the likely mission directive from Reunion: gain control of it, run it, report back.

Those orders hadn’t proven practical, when there’d turned out not to be a functional station or a capable human presence in Alpha system. Ramirez had had to improvise. Ramirez had rapidly discovered the only ones who could give him what he wanted were atevi, and Ramirez, one increasingly suspected, had been predisposed to think answers might come from non-humans: Ramirez had chased that assumption like a religious revelation once he found a negotiating partner in Tabini-aiji, and found his beliefs answering him. By one step and another, Ramirez had gone far, far astray from Guild intent: the mutiny had gone down to defeat, Ramirez had died in the last stages of his dream.

So what could Sabin do now but lie to the Guild one more time and swear that Ogun was back there running Alpha Station’s colony, everything just as the Guild here hoped?

She could of course immediately turncoat to Ogun and all of them and tell the Guild the truth, aiming the superior numbers and possibly superior firepower of the station at an invasion and retaking of the ship… from which she had stripped all trained resistence.

That was his own worst fear, the one that made these corridors seem very, very spooky and foreign to him. His colonist ancestors had taken their orders from these corridors. His colonist ancestors, when they were stationers, had obeyed, and obeyed, and obeyed. Everything had gone the Guild’s way for hundreds of years.

Now he was here, without escort, lonely, loud steps in this lower corridor; and he very surely wasn’t what Reunion envisioned Alpha to be. The ship’s common crew had mutated, too, learning to love fruit drinks and food that didn’t grow in a tank.

But now they confronted authorities so old in human affairs that even a colonist’s nerves still twitched when the Guild gave its orders and laid down its ultimatims. They scared him. He didn’t know why they should: he hadn’t planned they should when they left Alpha, but here at the other end of the telescope, Guild obduracy was real. Here it turned up from the very first contact with station authorities. That absolute habit of command.

And Sabin pent up all four shifts of her own crew rather than trust them to meet the Guild’s authority face to face. Jase himself hadn’t given the order to release the lockdown.

Get fueled. Get sufficient lies laid down to pave the gangway. Get them aboard and then tell the truth. It wasn’t the way he’d like to proceed.

It wasn’t the way Jase would like to proceed: he believed that the way he believed in sunrises back home.

But he had no answers, no brilliant way to handle the situation that might not end up triggering a crisis—and right now he feared Jase was very busy up there.

He needed to think, and the brain wasn’t providing answers. Blank walls and empty corridors drank in ideas and gave him nothing back but echoes. No resources, no cleverness.

Was the Guild going to give up their command even of a wrecked station in exchange for no power at all, and settle down there in the ’tween-decks as ordinary passengers? Not outstandingly likely. They’d want to run Alpha when they got there. They’d assume they ran the ship, while they were aboard.

A damn sight easier to believe in the Guild’s common sense in the home system, where common sense and common decision-making usually reached rational, public-serving decisions—and where the government didn’t mean a secretive lot of old men and women bent on hanging onto a centuries-old set of ship’s rules that didn’t even relate to a ship any longer.

Insanity was what they’d met.

The Guild might even have some delusion they could now take on that alien ship out there, because Phoenix had its few guns for limited defense. Take Phoenix over, tell the pilots, who’d never fired a shot in anger, to go out there and start shooting at aliens who’d already seen Guild decision-making?

Not likely.

If the Guild had any remains of alien crew locked up in cold storage, they might be able to finesse it into their hands—claiming what? Curiosity?

That wasn’t going to be easy. Not a bit of it.

But they had an unknown limit of alien patience involved. Whatever had blown the station ten years ago argued for alien weapons. He believed in them.

And while Phoenix had been nine years making one careful set of plans that involved pulling the Guild off this station—bet that the Guild had spent the last nine years thinking of something entirely contrary.

Steps and echoes. He was up here—down here—from relative points of view—trying to shed the atevi mindset, trying to think as a human unacquainted with planets had to think, up on the bridge—

Oh my God . The planet. Up on the bridge.

That picture on Jase’s office wall. The boat. The fish.

There were no atevi in the photo, just a sea and a hint of a headland beyond. But the evidence of that picture said Jase had been on a planet, which indicated a very great deal had changed from the situation Phoenix had expected when it came calling at the station. More, it led to questions directed at Jase, and questions led to questions, if Jase didn’t think to shove that picture in a desk drawer before he let the Guild’s inspectors into the most logical place on the ship for them to want to visit: the sitting captain’s office.

Clatter of light metal. A cart.

A door working.

Food service cart. He knew that sound.

Galley was operating.

“I’m walking down to the galley,” he muttered to his listening staff, and he turned down a side corridor and did that… first acid test of his anonymity. Try his crew-act on cook and his staff. Test the waters.

Maybe borrow that food cart—a viable excuse to move about the ship during a common-crew lockdown.

He’d walked considerably aft through the deserted corridors. And down a jog and beyond wide, plain doors… one had to know it was the galley, as one had to know various other unmarked areas of the ship… he heard ordinary human activity, comforting, common. Men and women were hard at work as he walked in on the galley, cooks and aides filling the local air with savory smells of herbs and cooking, rattling pans, creating the meal the crew, lockdown or not, was going to receive.

He dodged a massive tray of unbaked rolls in the hands of a man who gave him only a busy, passing glance.

Then the man came to a dead stop and gave him a second glance, astonished.

A year aboard—and he knew the staff, knew the faces. They knew him by sight. Not at first glance, however. That was good.

And without an exact plan—he suddenly found at least a store of raw material. He waved cheerfully to the man with the tray and, spotting the chief cook over by the ovens, walked casually toward him.

“Hello, chief.”

“Mr. Cameron.” Natural surprise. Hint of deep concern. “What’s going on up there?”

“Well, we’ve got a little problem,” he said. People around him strained to hear, a little less clatter in their immediate vicinity, quickly diminishing to deathly hush. He didn’t altogether lower his voice, deciding that galley crew just slightly overhearing the truth was to the good—gossip never needed encouragement to walk about.

So he began the old downhill skid of intrigue. He wasn’t Bren Cameron, fresh off the island and blind to the world. He was, he reminded himself, paidhi-aiji—the aiji’s own interpreter, skilled at communication, skilled at diplomacy between two species—and used to the canniest finaglers and underhanded connivers in Shejidan. “Everything so far is fine, except station has locked the fuel down tight and wants Sabin in their offices and their inspectors on our deck, as if the senior captain had to account to them .” That wasn’t phrased to sit well with a proud and independent crew, not at all. “So do you think I could get a basket of sandwiches to take up to the bridge as an excuse to be up there, to find out what’s going on?”

The chief cook, Walker, his name was, listened, frowning. “What do you think’s going on, sir? What in hell do they want, excuse my french, sir?”

“They want us to say yessir and take their orders, and I don’t think the captains are on their program. I don’t officially speak for Captain Graham—but I’ll take it on my own head to go up there and find out if he has orders he doesn’t want to put out on general address. If you could kind of deliver a small snack around the decks and at the same time pass some critical information to crew in lockdown, it might be a good thing—tell the crew back the captain, tell them don’t mention atevi or the planet at all if these Guild people ask, no matter what. If they’ve got any pictures that might give that information, get them out of sight. And don’t do anything these people could use for an excuse for whatever else they want to do. Senior captain’s taken all our security with her, trying to make a point to the Guild on station. Captain Graham’s kind of empty-handed up there, worried about them taking over the ship.”

A low murmur among the onlookers.

“Taking over the ship,” he repeated. “Which is what we’re going to resist very strongly, ladies and gentlemen. Captain Graham is worried: Captain Sabin is risking her neck trying to finesse this, and Captain Graham’s attitude is, if they even try to claim her appointment as senior captain of this ship isn’t official without their stamp of approval, gentlemen, there’s going to be some serious argument from this ship. Captain Graham’s worried those investigators may make matters difficult up on the bridge. And I want some excuse to go up there and look around and make absolutely sure the bridge crew’s not being held at gunpoint right now.”

Quiet had spread all through the galley. Not a bowl rattled.

“So what’s to do, sir?” Walker asked.

“Back Captain Graham. Be ready, if there’s trouble; if there’s some kind of incursion down here, squash it. Spread the word. We’ve got that alien craft lurking way out there, watching everything that’s going on, expecting us to straighten out this mess and so far being civilized about our going in here to get the answers out of the station administration. I know the aliens are waiting. I talked to them, so far as talk went, and right now they’re being more cooperative than the station authority—who’s got an explosive lock rigged to keep us from the fuel we need, did that word get down here? And a sign on it telling us in our own language it’ll blow up in our faces. I don’t think the aliens could read that sign. Guild won’t say a thing about that ship, and now they’re making demands as if Sabin was to blame for their station having a hole in it. The Guild is holding the fuel against the senior captain’s agreement to walk into their offices and present her papers, as if they had the say over this ship, which she doesn’t agree they have.”

“No, sir,” one man said, and a dozen others echoed.

“But there we are,” Bren said. “We don’t know why the innocent people we came here to rescue aren’t rushing to get aboard and get out of here. Or why they didn’t just board, the last time this ship docked. We believe there’s people on that station that might like to board. But they’re not showing up, and the only communication we’ve got is a sign telling us hands off the fuel. That’s why the order hasn’t come to walk about. I want to get up there to lend Captain Graham some help, and I figure there’s less suspicion about galley bringing food in—so can you figure how to make me look like I’m on galley business?”

“Bridge wants more sandwiches,” Walker growled, with a look around, and personnel moved, fast.

Then Walker asked him outright: “What’s gran down there thinking about this situation? The atevi backing you?”

“Backing your captains, while Captain Graham’s taking every measure not to let any outside inspector near five-deck. We don’t want to explain the whole last nine years of our alliance to a Guild that’s in a standoff with an alien ship and not leveling with us. We don’t want them scared. Gran ’Sidi perfectly well understands the need to finesse this operation. Right now you’re likely the only group that’s free to move. You can carry messages, receive information, get it back here, carry signals, carry plans , if it goes that far. I can’t stress enough how important it is we keep the peace down here, keep your freedom to move, and just stay ready to back the captains.”

“Damn right,” Walker said, and, an assistant turning up in the aisle with the requisite basket atop a loaded drink-tray, Walker took the goods and handed the exceedingly heavy arrangement to him. “Anything you need, sir. And anything your people down on five-deck need, if you’re having to stay locked down. Same to the bridge.”

“I’ll pass that on,” Bren said earnestly, restraining the habitual bow. “Thank you, chief. Thank you all.”

He walked out, one more member of cook’s staff on a mission involving sandwiches, drinks, and now the bridge. He didn’t know a thing, didn’t have an ulterior motive, didn’t have a badge or an ID. No one on the ship ever had a badge, the same way they didn’t put up directional signs. They were all family. Outsiders, once the spotlight was on, stood out like the proverbial sore thumb.

But he didn’t look that foreign, by the galley worker’s initial reaction. And everything he’d just said in ship-speak, he was sure Jago followed well enough, at least the gist and intent of it, especially since he was sure Ginny had made it to the security station by now, to provide help with the nuances.

He carried his load down the main corridor back to the lift, not, at the moment, worrying about Guild agents inside the ship. He was just an ordinary fellow, that was all, a crewman whose greatest fear was getting his food orders mixed up.

He maneuvered his tray inside the lift, knuckled the requisite buttons, held his tray steady and kept his face serene.

One deep breath before the door opened. He walked out beyond that short partition that screened the lift area from the bridge.

A gray-armored man stepped out from the other side of that partition and leveled a rifle at him.

Well, well, that was different. He had no trouble at all looking discomfited, while his eye took in an immediate and tolerably complete snapshot of the situation—Jase angry and alarmed, the bridge crew sitting idle stations on a ship that wasn’t moving, while four gray-armored men, one gray-haired, gray uniform, likely a technician, leaned over the number one console, the beseiged tech leaning inconveniently far over, but not yielding his seat.

“Sandwiches, cap’n. The chief thought you’d need ’em.” Bren used his best and broadest ship-accent, simply ignored the armed threat and blundered on, presenting the tray to Jase, who waved him on—no exchange of glances, nothing but a set jaw and a situation in which an intruder from belowdecks was oh-very-welcome to walk around, the captain saying nothing about it at all.

Anxious eyes fixed on him at various places, techs recognizing him and doing a masterful job of not showing it. Hostile Guild stares assessed him as a nuisance, a fool on a job mostly below their radar, and passed him.

“Dunno what we got,” Bren said to the first bridge tech, looking at the sliced side of sandwiches, while Jase resumed his argument with the Guild agents. He let the woman take a pick of fillings, then wandered over to the Guild investigator. “You’re from the station.” Brilliant observation. “I’ll bet you’re glad to see us.”

“Cameron.” Harsh admonition from Jase. A clear warning. “Do your job.”

“Yessir.” He turned a charitable face to the Guild investigator. “Want a sandwich, sir? I got a few extras here.”

“No,” the intruder said.

“I’ll take one,” the beseiged chief tech said, the one with the Guild man leaning over his shoulder.

Bren let him take a pick while the argument went on, Jase with the Guild. “In absence of the senior captain’s direct order, no.”

Bren started down the row, handing out drinks and sandwiches, his back to the problem. Worried eyes met his, one after the other, warning, desperately asking.

“Cook’s compliments,” Bren said, hoping to God nobody recklessly tried a whispered message. He was used to acute atevi hearing—and the electronics that routinely amplified it. There was ample evidence of electronics on the intruders, doubtless amplification, and he strongly suspected some sort of link back to Guild headquarters, but maybe not as good a link as they might want, given two hulls and the technical facts of their connection. He didn’t need to pass specific messages. His very presence with a tray of sandwiches said cook knew, so crew below knew and atevi and Mospheirans knew. He was no threat—but atevi had a reputation for stealth and silent interventions. Don’t panic, his being here said. We’re aware. Gran ’Sidi is aware. The captain has armed, skilled support.

Jase’s ongoing debate with the Guild—he couldn’t hear it all, but it seemed the Guild inspectors demanded to see the log and Jase kept saying no, the senior captain had ordered to the contrary, the senior captain had to authorize that, and the senior captain wasn’t here, so hell would have icicles before any non-crew touched a board.

“Not until she’s on this deck and she changes the order,” Jase said. Perfect imitation of a subordinate with one bone to chew and absolutely no imagination of doing anything to the contrary. The Guildsmen, in their turn, wanted to call their headquarters and get that direct contact with Sabin.

“Won’t matter,” Jase said, obdurate. “Won’t matter. Until she’s on this deck, no matter what she says to the contrary, I have my orders. Nothing she says is going to mean a thing to me until she’s back here and she can say so on our deck.”

For the first time a certain method appeared in Sabin’s madness: you asked, I went, now you want it different. Sorry. You’ve blown your cover and I won’t do a thing until I’ve got answers.

One hoped to God nobody had tried to apply force to Sabin and her security team. One hoped she reached the Guild offices, took her stand and explained to the Guild why they had to turn over all alien remains and materials in their custody and pack their suitcases for a long trip.

Meanwhile there seemed to have been no word from her. Jase stood his ground, heard all the arguments, nodded sagely—and went repeatedly back to a simple shake of the head and a repetition that he wasn’t going beyond Sabin’s orders.

Bren coasted past, dumbly made a second attempt to hand the captain a sandwich and a drink in mid-argument.

“Cameron,” Jase said in warning. “Just stow it.”

“Yessir,” he said, as if he’d understood some silent, peeved order, and wandered off to the administrative corridor, the Guild agents’ suspicious eyes on his back. One of them was going to follow. Not good.

He took his tray and basket into Jase’s office, whisked the damning picture off the shelf and under the basket atop the tray, then set down Jase’s sandwich and drink just as the shadow appeared in the doorway.

And came inside.

“Can’t leave you in here, sir.” Bren made his voice perfectly polite, a little nervous as he tucked his empty tray close. With a free hand, he waved the agent toward the door. “I got to go, sir, if you please. Can’t leave anybody in the captain’s office. Regulations.”

The agent edged out, scowling, casting a look over his shoulder. Bren walked out and happened to lock the door in the process.

He had one drink container left. He blithely offered it to the agent—and let that cold answering stare go all the way to the back of his eyes. His only personal problem was getting back with the tray and reporting to cook. He didn’t know what the captain was doing. He didn’t know what the problem was up here. It wasn’t his job. The galley was. Captains and officers solved the big problems. It was all way over his head.