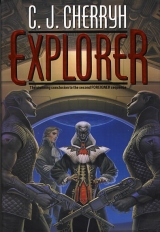

Текст книги "Explorer"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

“To keep the ship out there from getting it,” Becker said.

“They’d do what they like. We’re the only entity that would read that sign. And we’re the only ones that sign would stop, aren’t we? Sounds like a bid for a negotiating position, to me.”

“In case we were gone and you came back.”

Listeners in the corridor hooted.

He translated that exchange into Ragi.

“Ha,” Ilisidi said, and leaned both hands on her cane. “A posthumous thought to our safety. Not likely.”

“The dowager says, Not likely. And I don’t need to translate the crew’s opinion.”

Becker was red-faced and thin-lipped.

“Beck,” another said, “if she’s from the planet at Alpha, she’s not the one that hit us. Neither’s the Alpha colonists.—My name’s Coroia, sir. And I’ve got two kids. And we’re in trouble, Beck.”

“Shut it down!” Becker shouted, and atevi security reacted—simply and quickly, a drawn wall of weapons. Cajeiri had ducked against his great-grandmother for shelter. And now tried to pretend he hadn’t done that.

Ilisidi lifted her hand. Weapons lifted.

“Sorry,” Bren said. “My personal apologies, Mr. Becker. They don’t raise their voices in the presence of authority. An intercultural misstep.”

Becker was shaken, the more so as apology undermined the adrenaline supply.

“You can advise them keep their damn guns safed.”

“We each have our customs, Mr. Becker. Back at their world, they’re taking precautions necessitated by your making enemies out here. They came to welcome you to a safe refuge. You haven’t got any allies, as seems to me, except us, except them. As seems to me, you’re stuck out here in a station with a hole in it—while we have a ship that works. So believe me: we’re the only game worth playing, the only one that’s going to give you any chances. I’m extremely sorry for your family, Mr. Coroia, if your Guild stands us off. You’ve got no defense, no agreement with your neighbors, no trade, no future, so far as we see, and we offer you all of that. But you persistently say no—not because it’s sensible, but because you’re blindly loyal to a Guild leadership that sent you here. The position you’re taking isn’t even good for your Guild, gentlemen. They’ve got an angry ship waiting out there. What do they plan to do about it? We’re not going to go out and attack it for you. We’ve got a world behind us that’s at risk if you go making wars, and we won’t shoot at it.”

Support in the ranks was wavering. It was evident on the other faces.

Even Becker looked less certain. “We’ve got only your word for what’s going on.”

“You’ve got proof in front of you, you damned fool!” That from Polano, with Kaplan, out in the corridor, an outright explosion of anger. “I’ve got two cousins on that station, who may be alive, and I don’t want to leave them here, mister! Use good sense!”

“Mr. Polano,” Bren introduced the complainant. “Who has a point. What’s so difficult about dealing outside our species? We do it daily. We may be able to get you all out of this. But we need straight answers.”

“Listen to Mr. Cameron,” Kaplan said, and Polano and the crew behind him added their own voices.

“Straight answers,” Becker said, and looked at his mates, and looked at him, and looked at Polano and back. And at Ilisidi and Cajeiri, with a far greater doubt. “That’s a kid?”

“Aged seven,” Bren said.

“ Seven. ”

“They’re tall,” Bren said dryly. “That’s exactly the point, isn’t it! They’re not us. But you’re still welcome aboard. You and your kids. Your wives. Your grandmothers. We can get you out of here and go where your kids have a future. You’ve got to have somebody you care about.”

He was making headway with the others. Becker, however, scowled. “The Guild’s not going to approve anybody leaving.”

“Because they’ve got such thorough control of the aliens out there? I don’t think so.”

Clearly Becker had thought he had an answer to that point, and now that it was on the edge of his tongue, it didn’t taste right.

“Get us two things,” Bren said. “Fuel and the reason that alien ship’s out there. The truth about what happened six years ago. The remains and belongings of whoever tried to come aboard and negotiate with your Guild.”

“Negotiate, hell!”

“That’s what your Guild told you? Truthfulness with us hasn’t been outstanding.”

“Look,” Becker said. “Look. Give me contact with my office. I’ll call and tell them everything you’re saying.”

“And what you report won’t change their basic opinions in the least, will it? What matters most here, Mr. Becker? Braddock’s good opinion? Or people’s lives?”

“We’re not the sort to make decisions like this!” Becker retorted. “We’re not qualified to make decisions!”

“You’re not stupid, either. You’ve been waiting for this ship. It’s here. And now you think your Guild wants something else. What could it possibly want? Control of this ship? Your Guild’s sat here for most of ten years with a hole in the station and now they need to run things? No. Not a chance.”

Becker bit his lip. “Not mine to say.”

“If your families don’t get aboard, if nobody on this station gets aboard, do you want that on your conscience? Because, being on this ship with us, you will survive, gentlemen. You may be the only ones from the station that do survive, because without refueling here we can’t possibly rescue your relatives. But survive you will, and you can remember that you had a chance. You can think about that fact, you can regret that fact for the rest of your lives, in safety, back where we come from.”

“They’ve got a hostage.” The fourth man, who never had spoken, blurted that out. The other three looked appalled, but that one, white-faced, kept going. “That’s why the aliens haven’t come back. We’ve got one of them. That ship out there, it’s not shooting because we’ve got one of them alive on the station.”

For two heartbeats Bren stood as still as the rest; then, having stored up his wealth of information, he finally remembered to translate. “Aiji-ma, this last man appears to have suffered a crisis of man’chi, and to save his relatives from calamity, he claims the station holds a foreign prisoner… a circumstance he believes alone has protected them from a second attack.”

A very slight shifting of stance among listening atevi. This was information.

“Interesting,” Ilisidi said, leaning on her cane.

“You think you’ve got a hostage,” Bren said to Becker. “And this hostage is still alive?”

“Supposed to be,” Becker muttered. Then the inevitable, “That’s all we know.”

“Mr. Becker, we’ve got a problem.” The pieces of information began to add up, logical enough only to the otherwise hopeless, and weren’t at all comforting to a man who had to make peace with the pattern they made. “So our arrival disturbed the situation you thought you had, and now that the currents are moving, you don’t know what else to do. But my people have spent the last several centuries figuring out how to talk outside our own species. Rumor says the aliens won’t attack you while you’ve got this prisoner. I’d say that’s an increasingly thin bet, and the more we dither about it, the thinner it gets. Who is this person, where is this person, and has anyone successfully talked with him?”

That last was his greatest hope, that someone had broken the language barrier, that someone knew how to communicate with this species.

The listeners in the corridor waited. Ilisidi waited, hand firmly on Cajeiri’s shoulder.

“We don’t know anything,” Becker said, Becker’s answer to everything, and that provoked an outcry of absolute frustration from the human listeners. “Listen to Cameron!” somebody yelled, out in the corridor. “Idiots! You don’t mess with aliens!”

Becker was nettled. “We don’t know anything, dammit!”

“He’s supposed to be alive,” Coroia said. “But nobody knows. We guess he is, if that ship out there is staying where it is, or maybe they just don’t know.”

“There’s supposed to be alien armament,” the fourth man said. “They’re supposed to be copying it.”

“That’s a crock,” Coroia said. “If they’re copying anything, Baumann, is some popgun somebody hand-carried aboard the station going to stand off a whole ship ?”

That insightful question brought its own small silence.

“You don’t know even that much is the truth,” Bren said. “That is the point, isn’t it? You don’t really know why you’ve been safe for the last half dozen years. The reason you’re alive just hasn’t made sense, and now that ship sitting out there, with us having stirred the pot, is liable to do nobody-knows-what. Can you tell us where this prisoner is, and can you tell us how to get to him?”

“Get families safe aboard,” Coroia said. “Get the kids all aboard.”

“That’s mass,” Bren said. “Is there fuel to move this ship anywhere if we do board the station population?”

Fearful silence. Then: “The miners went out,” Becker said. “Mining went on, six, seven years ago. There’s supposed to be fuel.”

“And mining hasn’t been going on since that ship showed. You were waiting for us with a sign on the fuel tank saying, This will explode. How did you plan to get out of the mess you’re in without us?”

“We don’t set policy.” Becker winced as even his own comrades exclaimed in outrage, and he gave a nervous glance to the patiently waiting atevi present.

“After Phoenix left—” Esan had abandoned his braced, surly stance and stuck his hands in his hip pockets. “We mined. They came and poked their noses into our corridors. We caught this bastard. And since then they haven’t tried again. That’s as much as everybody knows.”

“This second attack,” Bren said. But suddenly he was aware of the onlookers parting.

Jase had shown up.

“I’ve been on this,” Jase said under his breath, Jase, who hadn’t gotten any sleep, “from my office. What’s this prisoner goings-on, gentlemen?”

“ They say an alien prisoner exists on the station,” Bren said, dropping into Ragi, as if he were talking to the atevi present, but it was just as much Jase he intended. “They say they mined fuel. They maintain this prisoner, with whom the station does not communicate, is the reason the foreigners have not attacked a third time. Supposedly the station captured some sort of armament. But what potency it has against that ship sitting out there is questionable.”

“Possession of this prisoner,” Ilisidi said, with a thump of her cane against the floor. “This prisoner, and the fuel for the ship. We have disturbed this pond. Ripples are still moving. Shall we sit idle?”

“No, nandi,” Jase said on a breath, in Ragi, in full witness of the detainees. “We do not.” And in ship-speak: “All right. Where is this prisoner, and what does he breathe?”

Good question, that. Very good question. The planet-born didn’t routinely think about the air itself.

“They wore suits when they came in,” Becker said. “Shadowy. Big. Straight from hell.”

Big certainly answered to the silhouettes they’d exchanged with the alien ship.

“You personally saw them?” Jase asked.

“On vid.”

Anything could be faked, Bren remembered. Anything could be made up. If it weren’t for the missing station section and that ship out there, Becker’s shadowy aliens could be an old movie segment from the Archive, and those in charge had shown a previous disposition to make up vid displays.

“Spill,” Jase said. “Spill. Now. Location of this prisoner. Location of Guild offices. Everything you know.”

Becker didn’t answer at once. “Guild wing is D Section,” Coroia said in a low voice, in that silence, “and if you give me a handheld and a pen, captain, I’ll show you.”

“The hell,” Becker said.

“Beck, I’m buying it. We haven’t got another way to defend this station.”

“Back off,” Becker said to the mutiny in his ranks. “Shut up.” Then, to Jase: “I’ll show you, myself. But I want my people out of this cage and I want our families boarded, fast as we can get them here.”

“In secrecy?” Jase asked. “You want to call your next-ofs and tell them start packing, and this isn’t going to trigger questions?”

Guild might eat and breathe secrecy, Bren thought, but he didn’t bet on family connections keeping a secret, not in a station where everybody was related. If Becker called his wife, would he fail to call his mother? And if the mother called Becker’s sister, where did it stop?

Becker surely saw the disaster looming. He didn’t entirely leap at the chance.

“We’ve got to tell the people,” Coroia said desperately.

“And start a panic,” Becker said. “There’s got to be orders. Central’s got to give orders, Manny.”

“They have to,” Jase said, “but they’re not doing that. We’ve warned them. But our senior captain’s disappeared on station. You had orders to come in here and scope us for whatever you could find. For what , gentlemen?”

“For irregularities,” Becker said.

“For a head count. For a check on who’s in command.”

“Yes, sir,” Becker said.

“So you’ve got that information, plain and clear. And then what was Guild going to do?”

“We don’t know, sir.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what we’re going to do.” Jase thumbed four or five buttons on his handheld. “And we’re not going to try to maintain this station up with an alien ship breathing down our necks. You wonder what that ship’s sitting out there for? It’s sitting out there because you’ve got one of its people and it claims this space, if you want my interpretation. It claims this solar system, it’s sitting there, probably taking notes on what comes and goes here, possibly communicating with others, and we’re not disposed to argue with its sense of possession. We’re getting the lot of you out of here, we’re establishing defenses back at Alpha, and we’re drawing the line there. This station is written off, to be vacated, best gesture we can make to calm this situation down. If we can get fueled and negotiate our way past that alien craft, we’re getting you, your families, and Chairman Braddock out of here.” He showed Becker and crew the handheld. “This is your own station schematic, gentlemen, straight out of Archive. With the damage marked. Right now, give me specifics, where this prisoner is, where the primary citizen residence areas are, where Guild command is, and where our senior captain’s likely to be, if she’s been arrested. If you want your kids safe—give us facts.”

Curious sight—Jase’s machine, Becker and the detainees vying to figure out the diagram through the thick plastic grid, nudging one another for a better view, and to point out this and that feature, suddenly a case of Guild loyalty be damned. Atevi observers were curious, too, more about the human doings than about the image—not least, Ilisidi, Bren was well sure, who kept her great-grandson protectively by her side as her security kept hands very near weapons, all of them sensing what they would call the shifting of man’chiin. Atevi would understand all the impulses to betrayal, all the emotional upheaval Becker and his men might suffer… and would not understand what pushed matters over the edge.

“Becker-nadi has seen the threat to his household, aiji-ma,” Bren said quietly. “He and his associates conclude their Guild has failed them and failed to deal honestly with them.”

The dreadful cane thumped down. “Observe, great-grandson. Mercy encourages a shift in man’chiin. Does it not? If it also encourages fools to think us weak, then we do not lose the advantage of surprise.”

“Yes, mani-ma. Shall we now attack the station?”

A thwack of Ilisidi’s finger against a boyish skull. “Learn! These are humans. These are your allies. Observe what they do. One may assume either reasons or actions will be different.”

Jase’s attention was momentarily for the schematic Becker had in hand, the things Becker was saying… the paidhiin both knew, however, the urges percolating through atevi blood and bone, potent as a force of nature: the aishi-prejid , the essential strength of civilized association, had to be upheld, had to be supported by all participants, and would survive, while the opposition’s command structure was tottering, its supporters seeking shelter. Translation: a weakness had to be invaded and fixed quickly, for the common good, even across battlelines. Among atevi, the web of association, once fractured, was impractically hard to repair.

War? That word only vaguely translated out of Ragi, and at certain times, not accurately at all; but as applied to the fragile systems of a space station utterly dependent on its technicians, the atevi view might be the more applicable.

“If we move,” Bren added in the lowest of tones, only for keen atevi hearing, “one fears atevi intervention will rouse fear and resentment among local humans. They will see you as dangerous invaders. If we are to go in to use force, it may be best humans do it.”

“Kaplan-nadi and his team are insufficient,” Banichi mut tered under his breath. “How can they improve on Sabin-aiji’s fate?”

That was the truth: if Kaplan and crew could get directly to the ordinary workers, they would have the advantage of persuasion—but getting to the common folk wasn’t at all likely. Sabin had tried walking aboard into Guild hands, and that hadn’t gone well at all. Ship-folk had no skill at infiltration.

Becker and crew, evidently the best the station had, hadn’t moved with great subtlety. The very concept of subtle force seemed, in this human population, lost in the Archive—along with the notion of how to deal with outsiders.

But to risk Banichi and Jago… even if fifth-deck atevi were the ship’s remaining skilled operators…

“ We can move very quietly,” Jago said. “We can find this asset.”

“If you go aboard, nadiin-ji,” Bren muttered back, “you can’t go without a translator.”

“We know certain words,” Jago objected in a low voice.

“You know certain words, but not enough,” Bren said. “If you go, I shall go, nadiin. Add my numbers with yours. I can reassure those we meet. I can meet certain ones without provoking alarm and devastation, which cannot serve us in securing a peaceful evacuation.”

Banichi listened, then moved closer to Cenedi, and there was a sudden, steady undertone of Ragi debate under the human negotiations.

“Nadi,” Bren said to Jago, who had stayed close by him. “Are we prepared for this move?”

“Always,” Jago said.

Oh, there was a plan. He’d personally authorized them to form a plan, but he had a slithering suspicion that, in another sense, plans had existed, involving the same station diagrams, from the first moment the aiji-dowager had arrived in the mix.

And meanwhile they had a handful of Guild operatives now crowding one another at the grid to point out the architecture of their own offices, pointing and arguing about the location of a prisoner none of them claimed to have seen—while crew who’d become spectators took mental notes for gossip on two-and three-deck. Openness? An open door for the crew? Jase certainly came through on that notion, and crew listened, wide-eyed, occasionally offering advice.

Jase had to be hearing everything, two-sided jumble, atevi and human. His skin had a decided pallor, exhaustion, if not the situation itself.

He listened.

And took his handheld and pocketed it. “Mr. Kaplan. Mr. Polano.”

“Sir,” came from both.

“Reasonable comforts for these men. Unauthorized personnel, clear the area. Nand’ dowager.” A little bow to Ilisidi, who, with Cajeiri, had been listening to Banichi and Cenedi with considerable interest. “Mr. Cameron. Same request. I’ll see you in my office, Mr. Cameron, if you will.”

Jase looked white as the proverbial sheet. Crew didn’t argue any point of it. Bren translated the request: “One believes the ship-aiji has reached a point of extreme fatigue, nandi, and wishes to withdraw.”

“With great appreciation for the dowager’s intervention,” Jase said with a little bow. Weary as he was, court etiquette came back to him. But he retained the awareness simply to walk away, not ceding priority to Ilisidi, a ruler in his own domain.

“Go,” Ilisidi said to Bren, with a little motion of her fingers.

While several Guild officers, having vied with one another in spilling what might be their station’s inner secrets, hung at the gridwork watching Jase’s departure. With alien presence and crew resentment both in their vicinity, their stares and their thoughts, too, following the ship’s captain who went away in possession of all they’d said.

They looked worried. And that lent the most credibility to the information they’d given.

Chapter 14

My picture’s missing,” Jase said indignantly, when Bren walked into his upstairs office. “Of all damned things for them to take.”

“Galley,” Bren said. And dropped into a chair. “I nabbed it.”

Jase gave a shaky sigh. “I’ll want it back.”

“You’re done in, Jase. Get some rest. Turn things over at least for two hours, while we analyze what we’ve got.”

“I can’t let the dowager take independent action.”

“ You’ve dissuaded her. Ship-aiji, she says. She accepts that notion. But in the way of things, if you have atevi allies, they’re going to act where it seems logical. We have to face the possibility we won’t get Sabin back. We might even have a worse scenario, that Sabin completely levels with the Guild and sells us out. The dowager wanted to know whether you can lead. I think she’s satisfied.”

Fatigue showed in the tremor of Jase’s fingers as they ran over the desk surface. “I wish I was.”

“Get some rest, Jase, dammit. Take a pill, if that’s what it takes. I wouldn’t like to predict our situation without a strong hand at the helm—so to speak, Jase. I truly wouldn’t. And you’re it.”

“We know there’s one alien ship out in the dark,” Jase said. “For all we know—there could be another. Or three or four. We know what we see. In my mind—and I don’t wholly trust my mind at the moment—agreement with them isn’t inconsequential here. Whether or not Sabin doublecrosses us, she doesn’t need to tell the station what the aliens out there want—not if they’ve been holding a hostage. The hostage becomes a bargaining piece, right along with the fuel. And Banichi’s talking about getting to him. Is that the deal?”

“About that, about the fuel.”

“Our technicians aren’t sure about that lock. They’re studying the problem.”

“So what are our options?”

Jase rocked back in his chair, thinking, it was clear. His eyes were red. His voice had gotten a ragged edge. “Our options are to sit here not fueling, not taking on passengers, and hoping the station’s hostage keeps the situation stable, or to give the situation a shove.”

“In what way?”

“Make life harder for the Guild. Put pressure on them to fuel this ship. Becker says the population’s about seventeen thousand—more than we thought. I hope he’s telling the truth. It’ll be tight, but we can handle that number.”

“Three things lend the Guild hope of holding out. Their control of the fuel. Us. And their hostage.”

“Four things. Their absolute control of what the station population knows. If they didn’t have the hostage, they’d have to fear the aliens. If they had to fear the aliens, they’d still have the fuel, and they’d have us—assuming we’d fight to protect them. They’re sure of that. But if they lose their lock on information—that’s serious. If they lose that, they lose the people.”

“And the station goes catastrophic in a matter of hours. With the fuel.”

“And the machinery to deliver it. If they lose control—things become a lot more dangerous. Everything becomes a lot more dangerous.” A tremor of fatigue came into Jase’s voice. “If we try to come in on station communications to tell the truth, their technicians can stop us cold. Anybody aboard who actually got the information, they’d tag before he spread it far.” A little rock backward in the chair. “They’ve got tech on their side, in that regard. But I’ve been thinking. There’s high tech, and there’s low tech. And your on-board supplies include paper.”

True. The ship didn’t regularly use that precious downworld item. Reunion wouldn’t. Atevi society, however—proper atevi society—ran on it. Paper. Wax. Seals, ribbons, everything proper as proper could be.

“Handbills,” Bren said, catching the glimmer of Jase’s idea.

“Handbills,” Jase said.

“If we do that—they’ll mob the accesses. And we can’t tell honest stationers from Guild enforcers.”

“They can’t mob us. We’re not hard-docked. Boarders will have to come up the tube, with all that means.”

“No gravity and no heat. If we don’t open fast, they’ll die.”

“They also can’t come at us in huge numbers. They have to board by lift-loads, and go where our lift system delivers them: the tether-tube is linked to the number one airlock. Ten at a time’s its limit, and we can override the internal lift buttons.”

“So you’re planning to do it.”

“I’m considering it as an option. I’ll write the handbills. I know the culture. I take it Banichi has an idea of his own.”

“Somewhat down your path. Getting our hands on this hostage. Knocking one pillar out from under their fantasy of safety. Safeguarding this individual before something happens to him.”

Jase nodded slowly.

“How we’re to do this,” Bren said, “I don’t know.”

“I’ll hear it when you do.”

“Meanwhile—get some sleep. Hear me?”

“In your grand plan to get hands on the hostage,” Jase said in a thread of a voice, “I take it you plan for atevi to execute this operation. And what happens when they’re spotted? This station is armed and wired for alien intrusion. Your people will be in danger from the stationers. And you’ll scare hell out of the people we want to talk into boarding the ship.”

“Both are problems. Maybe your handbills ought to just tell the truth. How’s that for a concept?”

“God. Truth. Where is truth in this mess? I’m not even sure I’m doing the right thing.”

“Get some sleep. Get some sleep , Jase.”

“The captain’s missing. Banichi wants to take the station. How in God’s name do I sleep?”

“Get a pill and lie flat. Do it, Jase, dammit! Let your staff rest. Trust your crew. Trust us, that we’re not going to pull something outrageous without consulting. We’re going to win this thing.”

Jase looked at him. “Tell me how we convince near twenty thousand scared people to trust us when they come face to face with the atevi Assassins’ Guild.”

“You’re on the ocean. Your boat goes down. You see a floating piece of wood. You swim for it. If your worst enemy spots it, too, you’ll share that bit of wood. Instinct. Far as we are from the earth of humans, we’ll do it. Atevi do it. It’s one of those little items we have in common.”

“You suppose those aliens out there have the same instinct?”

“May well. When the water rises and the world goes under, not just anybody, anything else alive becomes your ally.”

“I’m not sure I trust your planet-born notions.”

“Get some sleep,” Bren said, and got up to leave.

“I want my picture back,” Jase said.

“Cook has it. I’ll get it myself.”

“I’ll send down for it,” Jase said. “Get. Go. Do anything you can.”

He left. Left a man who, on the whole, had rather be fishing, and wanted nothing more than that for himself for the rest of his life.

But fate, and Ramirez, and Tabini-aiji, had had other designs.

He walked the corridor behind the bridge, talking to his pocket comm, giving particular instructions, already making particular requests.

“Rani-ji, I shall need the paper stores. Jase will have a text for us to print, at least five hundred copies.” He recalled, curiously, that five-deck had the only hard-print facility on the ship. Jase had known how to write longhand when he dropped onto the world, but nine-tenths of literate ship’s crew had had to learn how to write coherent words on a tablet when they first saw pen and paper. Read, no problem: dictate well-constructed memos, yes. But they couldn’t write; had never seen paper or written the alphabet by hand. Alpha and the crew had existed across that broad a gulf of experience—there was no shorthand explanation for the differences between Mospheirans and ship’s crew.

And twenty-odd of the atevi Assassins’ Guild were going to scare common sense out of the populace unless there was some immediate, visible reassurance to station that they were on the side of the angels. This was an orbiting nation that couldn’t fly; that universally read and couldn’t write; that knew gravity, but not a sunrise. That panicked at the flash of light and dark in the leaves of trees. Certain subtexts were unpredictibly lost when fear took over.

Someone had to make clear that atevi presence was there to help them. Someone had to demonstrate human cooperation with atevi. Seeing, in a very real sense, was believing.

And he had a clammy-cold notion where the paidhi’s job had to lie in this one.

Chapter 15

Jase, one hoped, was finally asleep, as Bren sat with his own bodyguard, his own staff, in the dining room, with his computer, with a pot of tea and a plate of wafers, and a number of pieces of printout littering the broad dining table.

“One has exhausted talk, nadiin-ji, where this Braddock-aiji is concerned. And that we have lost touch with Sabin seems no accident. Her departure left the ship with no skilled operatives, few that know anything of self-defense, this being a closely related clan, unused to internal threat. So Jase has no choice but appeal to five-deck.”

“Does he then conclude,” Banichi asked, “that Sabin-aiji is lost?”

“He is by no means sure.” Bren had his own doubts of that situation, and accurate translation to an atevi hearer was by no means easy. Aijiin had no man’chi. It all flowed upward. And that a leader could desert her own followers was a very strange notion. “She may have acted on her own, against the Guild. Certainly she was aware that she was taking most of our protection with her—except atevi. And she took our one known traitor—if traitor he was, to her. Neither Jase nor I know whether she meant to protect Jase from Jenrette, or Jenrette from Jase.”

“Perhaps,” Jago ventured, “she may not have rushed blindly into whatever trap they may have laid for her. She never seemed a fool. Perhaps she thought she took enough force to seize control of the station center; but why, then, take Jenrette?”

“That answer must be lost in the minds of ship-folk, nadiin-ji. A Mospheiran human utterly fails to understand it.”

“Perhaps she did confide in Jase,” Banichi suggested darkly.