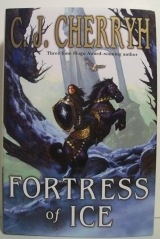

Текст книги "Fortress of Ice"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

He put on his better brown cloak, to look as much like his father’s son as he could, and walked down the hall, this time to the central stairs, keeping a slightly worried eye out for Aewyn or his bodyguard. He saw no one, which indicated Aewyn was somewhere other than his rooms. He went down to the main hall and so on to the stable-court door. Past soldiers busy with their own concerns, he walked out into the crisp air and sunlight of the courtyard, and, descending the steps at an idle stroll, he walked through the yard.

“Your lordship.”

He looked aside. The stablemaster had seen him, and diverted onto his track straightway with the air of a man bent on business.

His heart beat hard. “Sir,” he said respectfully and as innocently as he could manage. The stablemaster had the look of an old soldier, weathered and white-mustached, with no nonsense about him, and Otter’s every desire was to bow and look at the ground—but he had known, coming down there, that he might be caught and might have to try out his story on the stablemaster or the gate warden or worse.

“The boy says ye went out by dawn an’ took Feiny out.”

“I did, sir,” he said, light-headed with fright. “Paisi had to go home.” The story started to change its order, and its pieces, coming hind end first into the world. “Our gran’s taken ill. He had to go, and with the drifts and all, we couldn’t get down to the pasture. So I sent him on Feiny, with grain enough, and cover from the weather. He’ll be back, Paisi will. With Feiny safe and sound.”

The stablemaster’s brows drew together like a gathering cloud, and the frown deepened. “It’s a hard ride, at best. And that man o’ yours ain’t up to that horse, your lordship, forgive me. The boy’s a fool that didn’t ask what you was about. If we’d ha’ knowt, we’d ha’ provided a gentler horse.”

There it was. The boy had the blame and might take harm for it, and in the face of such bluff goodwill from the old stablemaster, he lost all resolve. He could scarcely track the story that had fallen out of his mouth already.

“It was my fault,” he said. “It was my fault, Master Kei. But Paisi is much better than I am on a horse. And he’s traveling with merchants.”

“Ha,” the stablemaster grunted, eyebrows lifting at that comforting news. “A message come, was it?”

“Yes, sir,” he said. The lie fell out of his mouth and took solid form. “From Amefel.”

“An’ this messenger, did he ride back wi’ your man, wi’ no change of horse?”

“Yes, sir.” It was the quickest way he could think of to dispose of any messenger, to have him go away with Paisi, and be with him, and keeping Feiny safe. “And he’ll be back as soon as he can.”

“Aye, your lordship.” The stablemaster let him go with a doubtful look, and Otter took the chance to escape, knowing that he had not done well. Now his tale had added a message, a messenger who hadn’t stopped to care for his horse in the Guelesfort stable yard, and no word how the message had gotten upstairs to him without passing the guards who watched everyone come in and out. He hadn’t thought about such details until the words were out of his mouth, and now the lie had more pieces. Which pieces ultimately couldn’t fit. And before too long the gate warden and the stablemaster might have a cup of ale with the Guard officers, and it was all going to break loose before he could talk to his father or Aewyn.

He didn’t know what to do, now, except to go on holding to the lie long enough to let Paisi get as far as possible, because if his father turned out to be angry, he could arrest Paisi, who might try to run, and the gods knew what could happen to him.

Toast and water had worn thin, by now, so very thin that his stomach hurt.

Fast Day was tomorrow, when he had to go without food or drink all day long, and when he would have to face his father and Aewyn and confess everything: he didn’t know if he could face it on bread and water. And he was near the kitchens, where he might not have too many chances to come today. Getting food was Paisi’s chore, but now Otter had to do it if he was to have any food at all; and he had to get himself ready in the morning, and not oversleep, not if he had to sit up all night. If his argument for sending Paisi away was that he was so sure he could manage without him, he had to do for himself and prove it.

So he turned toward the kitchens and climbed that short stair by the scullery, into a hall lit by a steamy little glass window, then into the huge arch of the kitchen.

The air inside was thick with steam and smoke, with the smells of wood fire and bread baking, the bubbling of meats and pies and cabbage, every sort of food one could imagine. A thick-armed maid spied him and fluttered him away from a floury counter edge, crying, “Oh, young lord, ye’ll have flour on your fine cloak, there. What would be your need?”

“Bread,” he said, relieved it became so easy. “Brown bread. Cheese and sausage, if you will.”

“Aye, your lordship. Don’t touch nothing, pray. Ye’ll get all floury. Stand there an’ I’ll fetch it. Is one loaf enough?”

“One black, one brown,” he said, giddy to find things suddenly falling his way and hoping it was an omen of Gran’s Gift taking care of him again. He stood in the rush and hurry of the kitchen, avoiding floury and greasy edges for the few moments until the maid came back, bringing him a small basket with a round loaf of crusty dark bread, a long one of brown, a small sausage, and what was likely the cheese wrapped up in oily cloth. “Thank you,” he said fervently, taking his leave, and edged his way back into the little hall and on up to the servants’ stairs, which led to the main floor.

He was just setting foot on the first step up that grand stairway when someone hailed him from behind, and not just any voice.

“Nephew?”

He turned back reluctantly, holding the silly basket, caught, plainly caught. The Prince, his father’s brother, who held his offices in the lower hall, had come out to overtake him and clearly meant business.

“Come,” Efanor said. “Can you spare a moment?”

“Yes, Your Highness.” He had never spoken two words to this man in all his time here, nor had Efanor ever addressed him. He caught his breath and tried to gather his wits as he made a little bow and followed Prince Efanor back to his writing room, a narrow, book-laden venue he had never entered. Books balanced crazily on the counter, and several, open, overlay the writing desk, sharing the surface with an inkpot and a quill left in it, writing interrupted. The Prince had chased him down on the instant, hunted him to the foot of the stairs, and all he could think was that a report had come in. The gate wardens must have reported to the Guard, and Prince Efanor had heard about it—which was the worst thing he could imagine. Efanor, who went habitually in black, and wore a silver Quinalt sigil as if he were a priest, was always so solemn and royal—Efanor advised Otter’s father, and judged cases, and handled the accounts, besides. He was as good as a priest, to Otter’s eye, a priest with the very strictest notions of truth and proper doings; and all he could think of now was to confess—to confess every lie, every sin he’d committed or thought of committing before this man could ever accuse him of his misdeeds, and maybe—maybe, because Aewyn had told him Efanor was not in fact as strict as he looked—to find some absolution, some penance, some way to mollify this man before he went to the king.

“Sit down,” Efanor bade him, and as he was about to sit down, whisked the basket from his hand. “Food for tonight?”

“Yes, sir.” He sat, and Efanor set the damning basket on the edge of the writing desk, behind which Efanor took his seat.

“You’re of the Bryalt faith.”

“Yes, Your Highness.” He wished he could sink through the stones of the floor, right on the spot.

“Are you a good Bryaltine?”

“I don’t know, Your Highness. Not as good as I could be.”

“Have you ever attended a Quinalt Festival?”

“No, Your Highness.”

“This is not Henas’amef, and the Quinalt holiday is not a time for frivolity of any sort.”

“Yes, Your Highness. No, Your Highness.”

“Nor a time for leading your younger brother into mischief.”

He was completely taken aback.

“I hope I have never—”

“Not yet. But boys being what they are, and two boys being twice one, it seems worth mentioning in advance of a public occasion.”

“I would never—”

“No, being a clever Otter and hard to catch, you would not. Your half brother is less cautious.” Efanor waved a hand toward the ridiculous basket. “Palace manners, however—you have a servant. You are not in the country. Let him carry such things. People note such behaviors as out of the ordinary, and they gossip. People will all too readily note youas out of the ordinary, and gossip about every little item that suggests oddity or scandal. Give them nothing. Be as unremarkable as possible, and be very wary about entraining your half brother in any schemes in public view or out of it. You have none such in mind, I hope.”

“No, sir,” he said faintly, desperately, and knew that he had lied, simply by failing to confess the truth, twice in the same hour. Was not three wizardous, and binding, if wizardry was possibly in question?

“Keep your chin up. Look all men in the eye. You are my nephew, in whatever degree, and my brother’s son. Whatis that hanging about your neck?”

His heart skipped a beat. He clutched the object in question. “A luck piece, Your Grace. My gran gave it to me.”

Efanor silently held out his hand.

He didn’t want to give it up. It was his luck. It was his tie with home and Gran. But he reluctantly fished it out of his collar and past the fastening of his cloak, and lifted the leather cord over his head.

Efanor took it, and looked cursorily at it as he laid the cluster of cord-bound pennies on his desk. “The queen herself is Bryalt, to be sure, but your gran’s form of the Bryalt faith verges just a wee bit closely on hedge-magic. You do know that.”

“Yes, Your Highness.” It was no more than a whisper he managed.

“You have been exemplary. I know. You are my brother’s, the result of one night’s youthful indiscretion. You carry Aswydd blood. You are taught by witchery—all these are matters marginally acceptable in Amefel, but I need not warn you, they are anathema in Guelessar. Yet my brother wishes to do you justice, so far as he can, and my nephew has taken to you and become your companion, so far as he can; and this places you under certain constraints of behavior—do you follow me?”

“Yes, Your Highness.”

“You will be under close public observation. No one can foresee how grievous might be the outcome if you were to be seen to violate propriety in services in the least degree. Do not fidget, do not cough, do not sneeze—and do not above all be seen to wear any charm, particularly to services, particularly within the premises of the Quinaltine.”

“Yes, Your Highness. It’s only a keepsake.”

Efanor gathered up the charm Gran had given him and gave it back to him.

“Tuck it away and do not wear it publicly until the day you cross back into Amefel. There is virtue in the piece, and that will not do, that will not do at all, inside the sanctuary. Most of the clergy is dull as stones, but there are reasons. Trust me in this.”

“Yes, sir,” Otter managed to say, and clenched it fast. Virtue? Could his uncle possibly feel witchery in it?

Efanor asked him, “Do you truly believe as the Bryaltines believe?”

“I studied writing with the brothers.”

“That is not what I asked.”

“I don’t truly know what the Bryaltines believe, Your Highness. I never had the catechism.”

“Indeed. Does the Quinalt service frighten you?”

“I heard—I heard somewhere, Your Highness, that they curse the Bryaltines. That scares me.”

A sigh. “An obscure part of the service. A nuisanceful point we oppose, but—” A shrug and a shake of his head. “Be patient with us Guelenfolk. The queen herself endures it. The liturgy is under review… under close review, considering the succession.”

Considering the succession. What did that possibly mean?

Then he thought of Aewyn and Aemaryen, whose mother was Bryaltine, and one of whom would grow up Bryaltine.

“Your quiet acceptance, like the queen’s, will be noted. Your presence with the family will disturb some folk, but, more important, it will reassure others that you can enter under that roof without fear. Your quiet, respectful attendance, your observance of Quinalt forms, will answer important questions and provide your father with answers to questions.”

“Questions, Your Highness?”

“About your mother’s influence.”

His cheeks flamed hot.

“Take no shame in my saying so,” Efanor added gently. “That influence may pose critical questions in certain minds, but not among us who understand the circumstances. Certainly your birth was none of your choosing. We hope to have a quiet, a decorous service. Servants do gossip. Be scrupulously observant. I see you are stocking up on food.”

The blush surely grew worse.

“You know you must consume all this food tonight,” Efanor said, “or cast it out before sunrise, to have no sustenance nor drink in your room… if you are observant.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Rise before dawn. Dress in the clothes provided you. I trust they do fit.”

“I’m sure, sir.” He was no such thing. He had had no time to try them. And he was too distressed to ask if what was provided him was proper. The very last thing he wanted was His Highness inspecting them in his room and finding Paisi gone.

“Join us in the lower hall just before dawn,” Efanor said. “Join the processional with the family. Sit with us, walk and sit in order just behind me, not next to Aewyn, and do not exchange glances with anyone. Have a pleasant look, however. A smile is not in order during the processional into the sanctuary, but you are permitted to smile after services, when you walk out in view of the city. Do you think you can observe all that?”

He attempted a smile, uncertainly, obediently, and, he feared, unsuccessfully. “I can, Your Highness.”

“Leaving the Quinaltine by daylight, one may smile. Smile, and never frown; but laughter—laughter should occur only when you are back well within the Guelesfort gates, no matter what your half brother provokes. This is a very grave matter: I cannot say that strongly enough. Mind, if any priest or His Holiness speaks to you directly within the sanctuary, look down when spoken to and answer him modestly and clearly. Especially try not to frown at any particular people. One notes you do this at times.”

“I never intended so, Your Highness.”

“Thinking, perhaps? A lad of deep thoughts?”

Another blush. “I never meant to offend anyone.”

“Well, let me see your cheerful face again.”

He tried. He tried with all his heart, then he thought it was the third lie, and the smile died a sudden death.

“Good lad,” Efanor said somberly, and gave him back his basket, a dismissal. “Don’t take this meeting as a rebuke. Take it for concern. I am concerned, young Otter, as a close kinsman.”

He felt a sudden urge to confess everything, to pour out all his sins to this man—it seemed for that one moment that he might make Efanor understand everything that had happened. But he hardly knew this priestly elder prince. He had always found Efanor a cipher, a stiff and formal sort servants skipped to obey and facing whom soldiers snapped to attention, even if he was notoriously holy and very scholarly.

“Your Highness,” he said instead, and stood up, with the silly basket in his hands.

“I’m told you read quite well.”

“Yes, Your Highness, I hope I do.”

Efanor handed him a little roll of parchment, tied up with brown cord. “This will explain in some detail the days of the Festival, what you should do on each particular day, and when you should rise and sit and expect to depart services.”

He took the little scroll and tucked it, along with the charm, into his bosom. “Thank you. Thank you very much, Your Highness.”

“And you won’t really need all that bread,” Efanor said. “My royal brother is hosting the family tonight in his chambers. It’s a custom we have. Your man will dine with the royal servants, where one trusts he will remain sober. Wear your second-best for the occasion. And appear at sunset.”

“Your Highness.” He hardly had breath left in him. And Efanor clearly had no idea Paisi was gone.

He bowed. Efanor favored him with a small smile, and stood up, and offered him the door.

He bowed again. He went out into the hall, on his own with the basket, and with the instructions, and with his charm, and his lengthening chain of fabrications, and went back toward the stairs.

He had lied the third time. Everything had, on the surface, gone well and smoothly. He had only to wear his second-best clothes and have supper with his father, and smile at the right times and not the wrong ones when they went in public. But his heart kicked like a hare in a trap. Was it tonight, not tomorrow, that he should tell his father the truth?

It had no certain feeling, the way his luck ran now.

Paisi, oh, Paisi, he thought. Be careful. Be ever so careful.

It might still be my mother’s working.

viii

IF PAISI HAD BEEN WITH HIM AS SUNDOWN CAME, HE WOULD HAVE LAID OUT all the right clothes for the dinner. He would have called for a bath well in advance and had the house servants carry the water up, and Otter and Paisi would have dressed in good order. But Paisi was somewhere on the road south now, perhaps approaching some village, or at very least one of the windbreak shelters they had used on their way, with a good stone wall for protection and a place for lawful fires.

So as the day dimmed in the windows, Otter did as Paisi would have done and laid his second-best out on the bed. He had no idea how to get a bath, which required informing someone: he had no idea who that person was.

He did know the source of drinking water, however, down by the inner well, where the whole Guelesfort got its water from a spring unstoppable by drought or hostile attack. It was cold as old sin when it came out, that was what Paisi had said, and miserable for washing, but it would serve in present circumstances. Otter carried it upstairs in the drinking pitcher, and none of the servants, lowest of the low, asked him his business.

He warmed a little water in the fireplace, for which wood was running somewhat low, and he used the washing basin for a bath, there on the warm hearthstones. He took pains with his appearance as he dressed, and found himself, as far as he could tell, acceptable. He had put the basket of food by the hearthside, to burn before morning, as Efanor’s little scroll informed him he should do. He had put the amulet in the clothespress in one of his gloves, where it would rest, safe from prying servants and accidents.

And he had on his fine dark brown, modest and plain, but very, very kind to clean skin. He thought he must look very fine, not as showy as he was sure Aewyn would appear tonight, let alone their father and the queen. But he was ready. His hair was combed. His linen was spotless. He hoped he would find the courage he needed. He hoped Aewyn was speaking to him and that he could signal the need to talk to him in private, when he could make peace.

He had been alone since dawn, and trembled at the thought of trying to confess his sins tonight, at least to Aewyn, as quietly as he could, and maybe, if he could possibly catch the king in private and without servants or guards—maybe he should just take the chance instead of waiting until tomorrow.

Tonight was sure—well, almost sure. Tomorrow—he had no notion whether he would have a chance then, either: it was only Aewyn and his mother, so far as he knew, who could get to him completely in private.

But there was still Aewyn to face. And that came first.

He left his rooms at the very edge of dusk and went down the hall and across the landing of the grand stairs, a long walk to the opposite wing that the royal apartments occupied. The guards here all knew him, and ignored him as someone who had leave to come and go, and the fact that the guards were still at Aewyn’s door informed him that Aewyn had not yet gone to his father’s chambers. He saw that with a sudden rush of hope.

The guards had to announce him: they did that when he simply appeared at the door and waited, and it was no delay at all before they let him in.

“There you are!” Aewyn said with a frown. “ Wherehave you been?”

“I—” he began, then lost the thread of everything.

“I tried to find you early this morning, and I couldn’t, so I took a sack of apples from the kitchen storeroom, and I took them down and paid the stableboy to lay them out tomorrow. Then the tailor showed up, and Master Armorer, and that was hours of standing.” Aewyn’s face grew worried, then, reflecting his. “Is something wrong? Where have you beenall day?”

Otter lowered his voice to its faintest. “In my rooms. I had to send Paisi home, on my horse.”

“Why?” Aewyn asked, hardly lowering his voice at all, then seized him by the arm and led him over near the tall diamond windows where there was a modicum of privacy from the servants. “Why? What happened?”

How did he know about Gran? That was the burning question. And he chose not to lie—but not to tell everything until Aewyn thought to ask him.

“Gran’s taken ill. And we didn’t count on the storms being so bad and there might not be enough wood small enough for her to carry, and sometimes the shed door freezes up with ice, so you have to take an axe to get the ice clear.”

“So Paisi left, and you helped him?” Aewyn’s eyes were wide. “I didn’t see you down at the stable when I was there.”

“We were out before it was more than half-light, and I rode and Paisi walked as far as the gate. We found merchants for him to travel with, so he’s safe. But I had to lie to the gate wardens up and down, and then the stablemaster’s boy, and then to your uncle…”

“To Uncle Efanor? How did heget into it?”

“He stopped me in the hall to tell me how to behave in Festival, and to tell me to come to dinner tonight.”

“But you’re completely by yourself now! Who helped you?”

“I had a bath, and I always dressed myself. And I had already gotten food for supper, except His Highness said I was to come to dinner.”

“Well, but you’re all alone! You can’t be by yourself. Come stay with me tonight!”

“I can’t. They’ll know, and they could still catch Paisi if they know too soon.” He hadn’t made up his mind, but all of a sudden what he told Paisi he would do seemed the best course. “I have to pretend he’s still here at least until tomorrow; then they won’t bother to chase him.”

“You think they wouldchase him?”

There was the hardest part, the part he hoped would get by. “We aren’t supposed to know about Gran, and we do, by a way that we’re not supposed to, and if we weren’t supposed to know, then we weren’t supposed to go, either, were we?”

“How didyou know?” Aewyn asked, and Otter took a deep breath and told the truth:

“Dreams. We both had the same dream, and Gran can Send a dream if she has to. She needs us. And Paisi had to go, and we can’t take a chance of Paisi getting caught. He has to get through.”

“But he iscoming back, isn’t he?”

“He will, as soon as he can. It’s three days to get there. Longer, with the weather. And he won’t try to come back until it’s safe on the roads. I told him not to try. But I’ll tell His Majesty tomorrow, after Fast Day, after Paisi’s had time enough to get clear away. And I’ll do my best to explain everything. I hope His Majesty may forgive me.”

“He won’t be angry.”

“I hope he won’t be. I was so scared your uncle knew—”

“Well, but he doesn’t, then, does he?” Aewyn loved plots above all things: his eyes sparkled. “And if you don’t have anybody to do for you, well, I can send you gifts, can’t I?”

“Can you send a whole bath?”

Aewyn laughed. “I can! I shall! And with the family dinner tonight, you won’t starve.”

“So. See?” He feigned complete confidence. “It’s all perfectly fine. And I’ll confess what I did, when I have to. But maybe nobody will ever notice Paisi isn’t here!”

Aewyn’s eyes fairly danced. “ Howdid you get away with the horse?”

“I asked the stableboy to saddle him.”

“And just took him out?”

“Paisi got breakfast from the kitchen, and I got Feiny out. We rode down to the gate before anybody was much on the streets, found some merchants who wanted a guard, and there we were. They promised to feed Paisi and Feiny both until they reach the crossing. And I sent Feiny out in all his gear, so he’ll be warm enough, especially with the traders’ mules and enough to eat.”

“That’s clever!”

“And I still have Paisi’s horse, if I need him.”

“He’s a piebald.”

“He has all his legs, last I saw.”

Aewyn laughed. “Well, he can’t keep up with mine. We’ll tell Papa what’s happened and get you another horse.”

“I can’t feed the one I have!”

Aewyn took on a quizzical expression. “The boy will feed him. He always does.”

“But at Gran’s… Gran can’t feed a horse. We’ll have to give Feiny and Tammis back when I go home for good and all.”

“You’re not going home!”

“I don’t know. I suppose that depends on whether your father sends me home for stealing Feiny.”

“He won’t! You’ll be here forever.”

Aewyn clearly had his mind made up on the point, and it was good to hear, but equally clearly, it was only Aewyn’s opinion, not the king’s.

“I hope to be here,” Otter said. He wasn’t sure about wanting it through spring planting, when Gran needed him, and once he’d said it the very ground under him felt shaky, as if nothing before him was the same as before. “I don’t know where I’ll be once the king finds out.”

“I’ll go with you to tell him.”

“After Fast Day. To give Paisi time enough. If soldiers came after him, I don’t know what he might do.”

“After Fast Day,” Aewyn said. “So we should go to dinner now. And we’ll have our secret.”

ix

OTTER HAD ONLY ONCE STOOD IN THE KING’S PRIVATE CHAMBERS, AND HAD NO idea where he was to go, beyond the little room he knew, but Aewyn knew the way to the inner halls, quite confidently. He marched them past all the guards, all the servants, arm in arm, at the last, a terrifying lack of manners, right into the room set for family dining.

The king was there, and they disentangled themselves and bowed respectfully and properly—bowed, likewise to the queen, Ninévrisë. Aewyn came to her for a kiss on the cheek.

“Mama,” he said, and returned her embrace.

Then Ninévrisë reached out a hand toward Otter, too, beckoning insistently. “Come,” she said, “come here, young man.”

Otter advanced ever so cautiously, his heart thumping. His vision was all of white and gold, beautiful furnishings, beautiful table, beautiful pale blue gown and a nearer and nearer vision of dark hair and a golden circlet, with the most luminous violet eyes gazing right at his. He was caught, snared, drawn forward, constrained to offer a hand, and to touch and be touched.

“Welcome,” the queen said, when he bowed and looked up. “Welcome, Otter.”

They said the queen had been with his mother the hour he was born. They said the queen had held him in her arms. He had never been able to grasp it for the truth—that she could be so kind to her husband’s bastard. He was utterly dismayed when she drew him forward and kissed him lightly on the cheek, in the way gentlefolk kinsmen did.

“Your Majesty,” he murmured. She was that. She was a reigning queen in all but name, in her own kingdom of Elwynor. And wizardry and witchery were not at all dead in Elwynor: her title, Regent of Elwynor, held place for the return of a Sihhë king. The Gift, Gran had told him, ran as strong in that line as it did through the Aswydds. He felt it tingle through her fingers, through the touch of her lips, so potent for the instant that it sparked through his bones and left him addle-witted and dazed, staring at her.

“Come, oh, come,” Aewyn said impatiently, dragging him by the arm, past Prince Efanor, and past the king himself, to claim a seat beside him at table, standing. They were only Aewyn, and Efanor, and the king and queen, and it was impossible to think only five people could eat at that great table, with all those plates and cups. There was holiday greenery, just as Aewyn had said, and birds served under their feathers, and pies, stacks of pies. It hardly seemed so grim, the Quinalt holy day, as it had sounded in Efanor’s little list of instructions.

King Cefwyn pronounced the prayer: “Gods grant us peace, prosperity, and our heart’s desire. The gods look down on us and bless us all.”

“So be it,” Efanor said quietly, “and bless them that serve and them that guard.”

“So be it,” the queen said.

“So be it,” Aewyn said, and dug his elbows into Otter’s ribs.

“So be it,” Otter breathed hastily, and everyone smiled and looked pleased with the occasion, while the whole room and its colors and smells seemed a haze around him. For an instant all he could think of was how to traverse the length of that table and speak to the man who had fathered him. He had no idea now what he would say or where he would start once he did start to explain; but now he remembered how he had lied to Efanor, who had been nothing but kind to him. The queen had just gone out of her way to be kind. And Aewyn—Aewyn, who was entitled to everything by right—he had involved Aewyn, delaying telling him what Aewyn now knew, and now expecting his help. He sat in the heart of the family, Aewyn most of all having brought him here. Aewyn and his mother had each had more than a slight choice about welcoming him under this roof. Aewyn had poured out his affection and his wealth and his kinship on him as thoughtlessly, as generously as breathing. And the queen, who most of all had every right to wish he never existed—he still felt the tingle of her lips touching his cheek and the warmth of her hand.

No group of people in his life had ever had so much cause to wish he had never been born, and no one had ever been so generous toward him, except Gran and Paisi. What had he done to deserve such trust, and what did he do to repay it but a piece of mischief growing worse by the hour: it was what Paisi had said—it was not the obvious thing that was the crime: it was not taking Feiny; it was the Sending and the Seeing, right in the midst of their holy days.