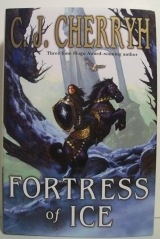

Текст книги "Fortress of Ice"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

“Rest,” the old man said, somewhere in his hearing, and near him a blue Line sprang into being. Blue fire ran along a wall, then branched, all in squares and rectangles, until all the space about seemed alight. They were wards, and they stretched on and on and on, burning blue and covering the very hillsides.

Safety, they informed him. Safe to sleep, safe to rest.

No, he insisted to himself. Not safe to sleep. Not while Otter’s lost.

iii

AUNT, THE WOMAN HAD CALLED HERSELF. Orien, Emuin had named his mother’s twin. Orien Aswydd. The name sent chills through Elfwyn’s bones. What have you done with my mother? he wanted to ask.

But he had no one to ask. He paced, too weary to walk, but unwilling to sink down and wait patiently in soft cushions. He thought of wreaking destruction on the place, ripping down the tapestries and shredding the cushions and making himself as ungrateful a tenant as possible—but that did nothing to win his freedom, and might put him in a worse place.

He did think to search the walls and behind the hangings for any hint of a second door or a cupboard, or something he might use as a weapon. The fireplace had no poker. There were no windows. And last of all he tried the latch of the door, in the foolish notion that, who knew? Perhaps his strong wish for a way out might make one: the world had not followed ordinary rules since Master Emuin had walked into their little cottage—or maybe not for hours before that.

He pushed the latch. It gave downward, and the door opened on a night-bound waste, a howling gust of snow, and shards of ice that rose up with the sound of swords, completely to bar his escape.

He slammed the door on that ungodly sight, slammed it and leaned against it, chilled to the bone.

It was not just ice. It was a cold so intense it had burned his throat and numbed his hands. It was magical, or sorcerous, part of the deep, unnatural winter that, as often as the snow melted, had blasted out more and more and more, and never quite ceased.

It was his mother’s winter. It was the winter when Gran died. It was the winter when his dream of welcome with his father had come to grief.

He wanted this winter to end. He shut his eyes and wanted it to end, with all the strength he had.

Your wards are pitiful. The voice came to him clear and strong, as if Lord Tristen himself had stood right at his shoulder. It occurred to him that he had made no wards at all, already assuming it was not his premises, and that he was the one held, not the holder. He blinked and lifted his head, stung by his own folly.

Or perhaps you forgot, the mocking voice said again, not in the air, but in his mind, and he knew it was notLord Tristen. Lord Tristen, whatever else, might have cast him out of Ynefel, but mockery was not his manner– furthest from it. Lord Tristen had been, whatever else, kind, and told him no simply by saying nothing at all.

Liar, he said to that voice, or thought it, then, gathering his courage, said it aloud: “Liar!” Not even his mother had lied to him. It seemed a low, mean sort of behavior, to pretend to be what one was not.

He moved, moreover, and walked the perimeter, and laid the wards once, twice, three times all about, in fury and defiance.

Wind blasted at him, as if every ward at once had blown inward. The force blew cushions off the couches and lifted his hair and blew his cloak back. His hand tingled, half-numb. His wards were flattened, useless.

And the same young man confronted him, standing near the fire… but the fire showed right through him.

“Well, well,” the young man said. “Temper rarely works where skill fails.”

Rage grew cold. The taunting minded him of the court of Guelemara, and the manners there, where detractors attacked with soft, sweet words. He bowed ever so slightly, drawing up the armor he had learned to use there– pride of birth, of all things, and a study of the rules of courtesy the other violated. “My name,” he said with that soft sweetness, “is Elfwyn Aswydd. I own it with no shame. Do you have a name, sir wisp?”

A hit. The young man’s chin lifted, and there was an angry glint in his eyes, before a smile covered it, showing teeth. “Elfwyn Aswydd.” He bowed in turn. “A name, indeed. Was it from your father?”

“You know who I am, or you would find something else to do. Your name, sir.”

“My name. My name. I think you know it. Where isyour brother?”

That hit, too, in the heart. He kept his gaze steady. “Clearly your interest is in me, and my mother is in this. Or my aunt. Are you a kinsman of mine, too, perchance?”

“No.” Again, he had nettled the young man. “Such lofty manners from a goatherd.”

“A goatherd who has a name, a noble one, and old. Why should I trouble myself with a wisp?”

“Oh, waspish lad. Unbecoming in a boy.” The young man left the fire, and light ceased to show through him. “Is that better?”

“I hardly know,” he said, jaw set, “since you have not the courage to go by a name, or possibly are ashamed of it. Areyou ashamed?”

“Otter, Otter, and Spider. One you call yourself and the other people call you behind your back. There are your names, boy.”

“Improve my opinion of you, I beg you. It’s reached very low.”

“Oh, pert beyond all good sense. Shall I call your mother?”

“Is she alive?” It should, if he were virtuous, feel some pang, no matter what she was, but she had taken too much from him, and he mustered no will to care whether she lived, at the moment, except the grief of what he wished he had had from her.

The young man snapped his fingers. His mother was there. Or his aunt.

“Son,” his mother said, in that intonation she had. “Are you being foolish?”

“Prideful,” the young man said. “Prideful and difficult. His brother’s name, I think, rouses a little passion in him.”

“That Guelen whelp,” his mother said. “That Guelen boy. He will be your enemy, Elfwyn. He is what he is, and he is Guelen.”

He turned his shoulder and looked at a tapestry in the corner, for some better view.

But he saw instead a room in candlelight, like a vision, a blond young man with a lean, strong jaw. That jaw was clenched, and those eyes, those blue Guelen eyes, looked at him with such anger…

“Your enemy, in time to come,” his mother said.

“Then he is alive,” he said, taking that for comfort.

“He will hate you,” his mother said. “He and you contend for the same power, and you cannot both have it.”

“Well enough,” he said lightly. “He was born to it.”

A blow to his shoulder spun him half-about, and he looked up into the face of the man. It was like facing Tristen in anger. Those gray eyes bore into him, and carried such force of magic it lanced right to the heart, painful as the grip on his arm.

“Do not cast away your birthright,” the young man said. “Do not resign what you do not yet possess… what you do not yet imagine, Elfwyn Aswydd. Will you see? Will you open your eyes and know the world to come?”

A woman appeared in his vision, a beautiful woman with violet eyes and midnight hair, a woman who looked right at him, and into him, and that expression was so determined and so open that it lanced right through him.

“This is your wife, your queen. This is Aemaryen.” The view wheeled away to a giddy sight of far-flung woods and farmland, villages and a towered city. “This is Ilefinian.” Another, even wider, with towers rising in scaffolding. “Guelemara.” A third, low-lying, against wooded hills, and beautiful beyond any of the others. “Althalen, where you will rule.”

“I shall rule, shall I?” He put mockery into his voice. “You dream.”

“Is that your answer? Aewyn may kill you, while you mewl on about friendship and gratitude. Do you think he’ll forget you left him, for safety? He will remember. His father will rescue him, and you and he will go down different paths. You asked Tristen Sihhë for wizardry, and he refused you– fearing you, fearingyou, boy, as he ought. You will surpass him. You will have a magic so much greater the ground will shake, and he saw that. He knew. Hesent you out, well knowing your gran would die if you went back just then—”

“Murdered by my mother,” he said, regaining his anger.

“Fate,” the young man said. “Fate had him send you out, in fear of you, fate drew you home again, fate had to destroy your gran to get you to Henas’amef, and fate drew you to the library, where your heritage mandated you be…”

“Sorcery killed my gran,” he said bitterly, flinging the young man’s hand away from him. “Sorcery killed her, sorcery wanted that thing found! I wish I’d never found it! I wish it had been you that died in that fire!” he shouted, looking straight at his mother. “That would have been justice! Now get away from me!”

“Your kingdom,” the young man said, behind him, “your kingdom will not be denied. You see how cruel your own sorcery can be, if someone stands in the way—like your gran. You assured she would die, when there was no other way to get you to the library. You assured you would lose your brother, when you enticed him out into the woods—he will grow up a bitter, angry man, all your doing. If you had only taken that book to your mother, none of this pain would have happened. Who else will you kill, until you take the place you were meant to have? I assure you, there will be more pain if you go on denying your own nature. There will be more deaths. Who next? Lord Crissand? That will throw the south into confusion. There’s no other lord who can rule as aetheling—except, of course, you, my prince.”

“I’m no prince, nor wish to be!”

“That is the very trouble, dear,” his mother said. “You blame me for the old grandmother. I assure you, I did nothing. It was you. I quite fear to be in your thoughts at all, until you know what you are, and understand what a power you do wield in the world. Everyone has to fear you, especially when you most afflict whoever loves you—innocents, like Gran, like your brother.”

“You’ve never lied to me,” he said in disgust. “At least I thought not. But you did. Everything you did was a lie.”

“My dear, you know you were born by sorcery. Can you think you might be ordinary? You were born to overcome my sister’s enemy, and do you know who that is?”

“I don’t care to know.”

“ Tristen. Tristen Sihhë. Now do you understand how very foolish you were, to be drawn to him? He looked you over. He saw a magic too potent to confront.”

He outright laughed. “A ridiculous boy who couldn’t light a candle, let alone a proper fire, to save himself from freezing. He saw someone too stupidto teach, with too many entanglements with sorcery. Forgive me, Mother, but I had all the ride home to think about that.”

“Then you quite missed the point. He entombed my sister alive, he warded meinto the tower above so I couldn’t break free, and accepting that imprisonment was the only way I could stay alive and stay near you—”

“Oh, spare me!”

“The old woman had power he lent. Oh, he is powerful, he is powerful beyond easy understanding. I fear him, but hefears you.”

“Ridiculous, I say.”

“You are not yet grown, son of mine! You are not yet grown, and even so the world bends around you—a piece of your power has come to you, not that you know how to read it, yet. Tristen would if he laid hands on it, I’ve no doubt; but there will come a day it comes clear to you and shows you the way to bring him down.”

He didn’t want to talk about the book, which clearly they knew he had, as they knew other things. Lies, he said to himself, all lies.

Aloud, he said: “All I wish is to be out of here. And, see? It failed. My wishes have no success at all. Fortunately, I put little hope in them.”

“So young, so bitter,” the young man said. “So impertinent toward your lady mother. She has endured years of prison for your sake, endured them teaching you to hate her, mistrust her, all these years. Endured blame, when your own rebellion killed those around you…”

“A lie. I will not forgive you thatlie, sir wisp.”

“I hope you will, when you rule.”

“Then you’ll wait a long, long time, sir wisp!”

“You will rule,” his mother said. “You fear our taking the book from you, do you not? You could hardly be more wrong. The book is yours. It was always yours. It was the text old Mauryl used, and a wickeder wizard there never was than Mauryl: you saw him, at Ynefel—did Tristen point him out? The face above the door. He brought a dead soul back, in Tristen, one of the Sihhë-lords, by blackest work, and to counter him, Mauryl’s enemy brought you. So none of this nonsense about subservience to Tristen Sihhë: Aewyn will never forgive what you are—the very check on his power. Your dear brother, sweet child that he is, will learn what you are, and after a certain time, he will understand quite well that he faces a choice—between Tristen, who sustains his father on the throne—or you, whose destiny is to bring down his dynasty and put it under Sihhë rule, and one cannot readily think that he will continue to be your friend. He will remember his sojourn in the snow. He will take his path, as you take yours through the world, and, oh, my son, if you continue in friendship with him, it will be a verypainful conclusion, with only one outcome. I advise you, shed him now, and be only a remote enemy, not an intimate one. His sister will be your queen—”

“My own sister, too!” He was truly, deeply offended. And yet the eyes, the wonderful violet eyes, stayed with him, heart-wrenchingly intent on his. “Mother, that’s an abomination!”

“And youhave listened too obediently to the Quinalt and the Bryalt. Your queen, and your subject, your one love, or there will be no love at all for you in this world. And you will, like Tristen, live long, very long. Will petty rules matter so much to you, I wonder, when you rule?”

“Well, it’s no matter,” he said with a shrug, “since the sun will come up in the west before I rule anything. Even Gran’s goats. We gave them all away, so I suppose I have no subjects.”

“The pride of a king, certainly,” his mother said.

“The face of one,” the young man said. “The bearing and the manner, when he wills to use it. The Quinalt would have liked him better had he been humble. His speech, do you note, has the courtly lilt, but Amefin, not Guelen. Where did he learn that, I wonder?”

“Perhaps it was a spell,” his mother said. “It could walk out of my cell, with him. He could carry it wherever he wished, right past the wards. I gave him many such gifts.”

That chilled him to the bone. He refused to think he had carried his mother’s curse home with him. If that were so, he wasto blame for the fire.

“Well, well,” the young man said. “You have reasoned with him as best you can. Let your sister set him at his lessons.”

“My sister,” his mother said, and spun full about, her skirts swirling. They came to rest, and she looked at him again, but with a she-wolf’s look, a terrible, burning stare, and a smile he had never seen on his mother’s face.

“Nephew,” those same lips said. “Listen to your mother.”

“Leave me alone.” Horror overwhelmed him. “You’re dead. You’ve been dead since I was born.”

“Tristen is ever so much older than that,” his aunt said, “and you had no fear of him. I assure you, you should have had. He did recognize you.”

“My dead aunt and a wisp,” he said, drawing himself up. “Small choice I have.”

“He only wishes to provoke us,” the man said with a tolerant smile. “Be patient. We have time. We have as much time as we wish to take.” Both winked out, with a little gust of wind that disturbed the fire, and left him with a curse in his mouth and nowhere to spit it.

He stood for a moment, in case they might come back and catch him collapsed onto a bench. He stood glaring at the fire, then settled himself with as much dignity as he could muster, given aching legs and frost-stung feet and hands and face. He felt the pain of his injuries now, a pain that grew and grew, and stung his eyes with indignation.

Anger was very, very close to the surface, anger enough to wreck the room, anger enough to fling himself at the shards of ice that barred the door, and die that way, if that was all that would spite them. He had no other hope.

Anger will be your particular struggle. He recalled Emuin saying that. And of Aewyn: He is your chance for redemption and your inclination toward utter fall. Do you understand me?

If I betray him, he had said. And Emuin had said:

If you betray him, it will be fatal to us all.

He had not, had he, betrayed his brother? He had stayed steadfast. He meant to do so.

Emuin had said, too, regarding his mother: As near as she can come to love, she loves you.

Love, was it? Wrong in one, perhaps wrong in both. Perhaps Emuin had not seen as much of his nature as he ought…

Vision. Was that not the word Tristen had given him?

Seeing. Seeing things for what they were. Seeing the truth, without coloring it, or making it other than it was. Was that the beginning of wizardry, to know what a thing really was before one started to wish it to be something else?

Be Mouse, Tristen had said, Mouse, not Owl. Mouse looked out from the base of the walls, was low and quiet, and looked carefully before he committed himself. He more than looked, he listened, and measured his distances—was never caught too far from his hole.

He certainly had been.

And he had forgotten his other word. So much of a wizard he was.

Spider, Emuin had called him. Spider Prince. And he had said pridefully that he didn’t live in a nasty hole.

He was certainly in one now. He’d spun his little web, his wards, and Sir Wisp had smashed right through them without even noticing.

All he could do was do them again, and again, and again, and maybe, as long as he might be a prisoner here, he might do them well enough to be a nuisance, then a hindrance, then, maybe, a barrier… spinning his web, a bit at a time.

Patience.

Patiencewas his other word. Now he remembered it. Patience, and waiting to talk to Paisi, and waiting to get advice, and approaching things slowly—would have saved him so much grief.

Patience instead of anger. Patience instead of rushing into things headlong. Patience, and Vision… would have mended so much that had gone wrong.

Lord Tristen had advised him of the truth. Would someone do that, for his enemy?

Lord Tristen might. He would have, because that was his nature to deal in truth, not lies.

And what did that say, for the advice he had just been given?

Maybe it was time not to be Otter, diving headlong from this to that, nor Mouse, watching from the peripheries of a situation, but patient Spider, simply building, over and over, and over again.

He sat, hands on his knees, and rebuilt his path, from the cottage, to the woods, to the battlefield, to the bridge, to here, in the unnatural ice that argued for somewhere not quite of the ordinary sort. The fogs that closed in had delivered them here, and here, and here, and at the last, Aewyn, Syrillas, had outright been unable to go with him, or had resisted going, and what pulled him here had been too strong…

Too strong for Aewyn.

Or too foreign to Aewyn, being sorcerous in nature.

Sorcery was a path that might be open to him. He might learn it and use it.

But it did not mend its nature simply because he used it; and he did not think it would improve his own.

So there was wizardry, which Tristen had refused to teach him.

Make me a wizard, he had asked. Or, had it been: Teach me wizardry?

And Lord Tristen had said: You are not yet what you will be, and added, and I have been waiting for this question for longer than you know.

How did he hear that answer now, in light of what his captors had said he was?

Teach you wizardry? He remembered Emuin saying that. Useless. Teach you magic? I cannot. No more can I teach any Sihhë what resides in his blood and bone.

He had scorned the answer. He had disbelieved it.

And he named you, Master Emuin had said of Lord Tristen. Then I suspect he did see what I see.

And he had asked, disturbed: What did he see? What do you?

A conjuring, Emuin had answered him. A Summoning that opens a door.

What door? he had asked, straight back at Emuin. Make sense, please, sir!

And Emuin:

You govern what door, if you have the will. Do you have the will, Spider Prince?

A chill ran through him, deep as bone, a chill that had him shaking in every limb. He looked down at his hand, where, forgotten, Lord Crissand’s ring shone in the firelight, dull silver, and festooned with cheap silverwork.

It had not tingled since all this last mad course began. It had not warned him against Emuin. It had lain inert during their precipitate rush from Marna to Lewen Field to the river. It had not warned him of Sir Wisp or his mother. Perhaps his captors had killed the virtue in it. He wished he had given the ring to his brother when they were at the beginning of all this. Perhaps then Lord Crissand would have been able to find Aewyn, at least, and saved his father pain.

He wished… like the spider. He chained one wish to the other, starting not with what was impossible, but what was possible. He sat down before the fire, and wished one spark to fly out, and to land on his hand.

It flew. It landed. Without hesitation he seized it, and patiently wished the next thing. He wished the chill away, wished himself warm. One thing after another, one thing after another.

He wished Aewyn safe.

The fog appeared again—not around him—but where the door had been. He saw just the least glimmer of light.

iv

SNOW STILL FELL IN THE DARK, AND THEY RODE THROUGH THE REMNANT of walls… walls lit by ghostly blue lines, which Cefwyn himself could see tonight. He rode by Tristen’s side, Uwen just behind, and all around them, like a ghostly city, old Althalen rose, not just its foundations, but the outlines of its long-fallen towers, and the soaring height of domes greater than any in the realm. It was a glimpse of the Sihhë capital, as it had been, and a Marhanen king knew what his grandfather had brought low.

But things changed. There were bonds made. And the heart of that maze of blue light led to a simple place, a corner of what had been the palace, and a wall, where a tomb was set—they had not been near it a moment ago, but then they were, and Cefwyn had the heart-deep conviction Tristen had magicked them a bit, just a little, over a hill and down it.

He saw then a gathering of haunts, in a little low place, at that corner, ghosts that, at their coming, turned and stared at them with gray and troubled eyes, before they shredded away on the winds. Layer after layer of haunts fled their passage, wisps that left an uneasiness in the air.

But a young lad sat against that wall—no, he rested against the knees of a bearded old man, whose ghostly hand stroked his blond, curly head, and by that man stood, gowned in cobweb, Auld Syes, the gray lady—her, he knew for long dead; and on the other side, behind the old man he now recognized for the old Regent, his father-in-law, stood a woman in a shawl, who was his other son’s gran, likewise perished. These three had his son in their keeping, and his heart froze in him. He swung down before his horse stopped moving, and ran to his son, heedless of haunts or spirits or whatever magic might be here. He was an ordinary man. He brushed it all aside, and seized his son up in his arms, and hugged him as hard as he could.

“Ow,” Aewyn cried. “Papa!”

“He’s alive,” he called to Tristen and Uwen, who, likewise dismounted, were right behind him, and he looked around to thank the dead, at least– old friends, old allies.

But there was nothing there but a crumbling stone wall, and the stone they had set there for Uleman Syrillas.

“It was Grandfather,” Aewyn murmured against his collar. “And Paisi’s gran. And a lady I don’t know.”

The boy was half-frozen. He might lose fingers or toes. Cefwyn brought his fur-lined cloak about them both, and looked desperately at Tristen, who simply said, “Give him to me.”

He did that. He had not a qualm, having Tristen take the boy from his arms and pass his hands over him. Aewyn’s eyes shut, as Tristen let him down to the snow, then opened again, with a curious tranquillity, a wonder in them.

“You must be Lord Tristen,” Aewyn said faintly, catching Tristen’s hand. “My brother is lost. Find him. You can find him.”

“I have never given him up,” Tristen said, pulling him up by that hand, so that a father who had been very sure he had lost both sons, could touch one of them and be sure that he was real.

“We were by the river. And then here,” Aewyn said to him, “and I tried to hold us down, and he slipped away. I don’t know where he is.”

Tristen, however, had looked away into the dark.

“I know,” Tristen said. “I know. He has a trinket of mine.”

v

AEWYN WAS THE FIRST THING ELFWYN IMAGINED WHEN HE BUILT HIS WEB, Aewyn in the snow, as he had left him, and he imagined where he had left him, but he could not make that image stay—it broke apart, in fat flakes of snow, and drifted on the wind, threads taken apart.

The wind, however, was a constant presence out there. He constructed that, stirring the trees, raising the snow in little plumes.

Fire was another presence. He constructed Aewyn’s voice, telling him about maps, and a laughing fish, one evening by the coals.

He constructed Paisi, sitting by the fireside, and Gran, busy over her bread-baking. He recalled Uwen’s wife, and her fireside with the lump in the stones.

And then, very carefully, he began to spin the strands that tied him to Lord Tristen.

He remembered the table by the fireside in Ynefel, while the whole fortress creaked and groaned with the wind, where the stairs sneaked furtively into new places, and faces in the stone seemed to watch someone walking by. Curiously enough, he could not recall Lord Tristen’s face, nor his voice, but he could clearly recall Mouse, taking his single crumb—taking his little success, and immediately running for cover.

He recalled Mouse’s enemy, Owl, on the newel post, and could see the mad glint of his huge eyes. He felt a sting, and looked down at his hand, where a mostly healed nick reminded him never to trifle with Owl.

Be Mouse, Tristen had told him.

He immediately recalled another fireside, and an old man who had asked him if he could be a spider.

Spider he was, tonight. He wove his web. He had made his mistake right after that warning. He hadn’t trusted the old man: he’d held fast to Aewyn, but he hadn’t trusted the old man enough when he tried to take them with him.

He would, if he met him again.

He thought about his charm of old Sihhë coins, and saw a bowl of oil on water. If he had been a real wizard, he could have made it show him something. He would have seen the truth in it, and told the truth to his father, and nothing of what had happened would have happened…

He kept staring at it, patient, patient as he could be, waiting to see what he would see now that he had it back. He stared and stared at the water, and saw a fog come over the surface.

It was the best he could hope for, that fog. It had carried him here. He wished it larger, and larger, and larger.

Elfwyn fell into it, and kept falling, but he was patient. He knew there would be a bottom sooner or later and that he would find it.

When he did, it was white, a long stretch of white, but when his feet hit it and skidded, and when he started walking, it was just another snowy patch of ground. It looked like a road. In the dim snowlight he could see walls on either side, and a little wish, a very little wish, made the ring tingle on his finger. He knew what way he ought to go. It was strongest in one particular direction.

So he kept walking. He pressed the book that rode inside his shirt, to be sure it was safe. He had made one mistake with a message, and was not prepared to make another. It was still there. It felt warm against his skin, and he kept his hand pressed there for a long time—growing colder as he walked, over snow that made a sound convincingly like snow.

He could endure the cold. He had endured worse, and would have endured worse, where he had been. He was determined, if another fog showed itself and tried to take him back, that he would sit down, hold to the rocks around him, and simply refuse to budge until bright daylight.

But none did.

He might have walked in that way for the better part of an hour, before he heard a strange sound behind him that was neither the wind nor the occasional cracking of ice crust under his feet. It was that sort of regular sound, but many feet—like horses.

He stopped, turned, straining his senses against the night, and saw three riders slowly overtaking him. There was nowhere for him to hide. It hardly seemed likely his mother would be riding here—but then it was not terribly likely that he would be here, either. He wondered, with a little shiver of fear, should he try wizardry again, and attempt the fog that had betrayed him.

He tried to bring it. He meant to bring it. But:

“Elfwyn!” someone called, a ragged, youngish voice.

“Aewyn?” he called back, all efforts stopped for a heartbeat. “Is it you?” His mother was full of lies, and he suspected it and was ready to run, but he stood his ground when he heard:

“Son?” That was his father. He never mistook that voice. He planted both feet in the snow and stood fast, waiting, as the three, no, four riders reached him.

One was Lord Tristen himself. Another was Uwen, who reached down a hand to lift him up. But before he could take it, Aewyn slid down from behind his father and seized him in his arms, pounding him about the back.

“Elfwyn!” Aewyn cried. “I thought we’d lost you.”

“I came home,” was all he could think to say. He hugged his brother, and now his father had dismounted, and put arms about him, and pressed the breath out of him.

The ring all but stung him. He looked up sharply, at Lord Tristen’s shadowy form, at a Sihhë-lord in armor, with the white Star blazoned on him, the sight that belonged in Paisi’s stories and not in the world as it was now.

“My lord,” he said, though his own father, the king of Ylesuin, had a hand on his shoulder at the time.

“Get up behind Uwen,” Tristen told him, and Uwen rode near, offering his hand a second time. He took it, hand to wrist, hauled up aboard a powerful, broad-rumped horse to settle behind Uwen Lewen’s-son, while his father and his brother climbed back to the saddle of his father’s horse, and Lord Tristen waited in silence. Owl showed up, and flew a curve half about him, then sped ahead.