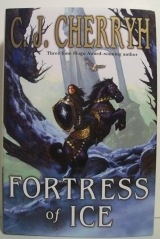

Текст книги "Fortress of Ice"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

That news relieved him so that he found no power of speech at all for a moment. He had come a long, hard ride, from Guelemara to Ynefel and back, he had come here to be blamed, even punished. Now he just felt worn thin, as frayed as the old cloak he wore, and shaking in the knees.

“I am very glad he forgives me, my lord. And I wish him all my love.”

“As you should. As you well should. Letters have flown about you, let me say, his to me, by his guard looking for Paisi, mine to him, his to me again by a second lot, come chasing after you. Now Tristen’s letter lost, gods save us, the gist of which we can only guess. I’ve no doubt Lord Tristen wishes me to take care of you, which I do, nevertheless, and to take care of your gran, which I have always done. If it there’s more, I’m sure he’ll be here soon to set it straight. If it was lost, he probably knows it. If it wasn’t regarding your welcome here—he’d probably have sent one of his birds.”

“In the storm and all, m’lord,—”

“Rough weather for them, no question, but they do get through, quite amazingly. He doesn’t need a rider to reach me. Or to reach your father, at greatest need. He can travel in ways that don’t regard the weather. Don’t fret about it. You simply stay at home for a bit, take care of your gran, let the priestly storms blow over in Guelessar—the Guelenfolk are always contentious at Festival. They’re forever seeing omens in the sky and portents in their ale. Their opinion comes and goes by spring. You don’t have any urge to do anything foolish, like ride off in another direction, do you?”

A canny question, Gran’s sort of question. Lord Crissand himself had the Sight, at least that, so Paisi had told him. A little of the Gift ran all through the Aswydd line.

“No, sir, I don’t want to ride anywhere, except to go back home and take care of Gran. Though after all that’s happened—I think I want to visit my mother.”

“An idle whim, or a burning need?”

“To tell her I’m back,” he said, hedging the truth: he couldn’t help it—it was old habit. He amended that. “To tell her that if everything that’s gone wrong lately is her doing, people see through her. And to tell her face-to-face who I am. I’m not Otter any longer, m’lord. I’m Elfwyn. That was what Lord Tristen said to me. My mother named me to spite everyone, particularly my father and the Guelenfolk. She meant to make trouble. But it’s my name, all the same, and Lord Tristen said I should carry it, so I will. I don’t have to be trouble to my father or to you, m’lord. I intend not to be. Once Lord Tristen’s heard what she’s been up to, I don’t think she’ll get her way any longer. I’m not sure after that, that I’ll ever be able to talk to her again. I don’t know, but I think she’s why things went wrong in Guelessar. And before I can never see her again—” He felt a tremor even thinking of so momentous a change in his life. “I want to see her once.”

“I wouldn’t upset her with threats, young sir. You see her once a year. That’s likely far more than you really want to visit her. Isn’t it?”

“I do want to see her. I want to remember what she looks like. She keeps fading, in my thoughts. And I want to see her this time, really see her. I need to.”

A frown, a thinking frown. “She’s our prisoner. Lord Tristen’s prisoner. And your father’s. You certainly aren’t hers. And I advise you to think of her as I do, as little as possible. But my guards will admit you there, whenever you wish.” Crissand passed him a small finger ring. “I lend you this. See your gran has all her needs. This has every power I would entrust to a son, and the guards all know it. See your mother if and when you choose.”

“Your Grace,” he murmured.

“This ring is more than a ring. It comes from him. It will guard you as well as supply you. Do not let it leave your finger.”

“I shall take great care of it, Your Grace, and bring it back as soon as—”

“Wear it for your gran’s sake, until Lord Tristen comes, to be sure you want for nothing, nor meet any need or obstacle this small thing can clear. This I lend you, since we do not have his letter, or know his intent: this will keep you safe until he gives me better advice. But know that if you do any mischief, this ring will not be good to you. Dare you wear it?”

“I,” he began, the ring clenched in his fist and that fist held against his heart. “Bringing this near my mother—if she took it from me—”

Crissand smiled. “Let her try. Challenge Ynefel? That is what it would be. I think it will rest very safely on your hand in such circumstances. She will be of no mind to touch it, or you, while you wear it.”

He put it on with trepidation. His whole hand tingled. “My lord duke,” he said, still perturbed, and Duke Crissand patted his arm and held it close for a moment.

“Your father’s son,” Crissand said, “far more than hers. Head-on and headlong, reckless in all things. I love him, but I do advise him, and you, as much as I can—be careful.”

“I shall be, m’lord.”

Crissand let him go then, and he bowed, and walked away, and bowed again, as respectful in this grand hall as people would be in leaving his father’s presence. He went all the way out the double doors, where the guard was, and Paisi was waiting for him.

“He gave me a ring,” he said, and showed it to Paisi, a silver band worked in vines and grapes. The guard saw it at the same time, he was sure of that, and he was extraordinarily proud to be back in his father’s good graces, and to have a thing from the duke of Amefel that the priests in Guelessar would never, ever countenance his wearing. It was a vindication, the very power he had hoped for to defend himself and Gran and Paisi, and he by no means intended to misuse it or to let any accident befall it. “So I can see my mother, he says. So he’ll know where I am. With this I can bring Gran anything she needs.”

“Will ye really see your mum?” Paisi asked, who must have been listening.

That settled him to earth. Not yet, he decided, although the thought had taken root in him that he should do it before Lord Tristen came, and before she thought she’d scared him into lasting fear of her, and before he lost all chance to see her.

He just didn’t want to face her yet, while he was still so tired he wasn’t thinking clearly. Tomorrow, perhaps. Tomorrow, he might come back into town.

iv

YOUR SON HAS RETURNED SAFELY, CRISSAND WROTE THAT SAME MORNING. WHEN your ward reached his house, he indeed went west, and reports he has seen Lord Tristen, who he says has informed him he should carry the name Elfwyn. He reports that the lord of Ynefel will come as far as Henas’amef, how soon and in what intent, unfortunately, I do not know. He says that Ynefel gave him a message for me, but that he lost it on the way, in bad weather. This alarms me, as I am sure it will trouble us all.

In the loss of Ynefel’s message, I have lent your ward the ring which Ynefel gave me, the nature of which I have made clear to your ward, and which he did not fear to take, except that he feared its presence might incite his mother. He has indeed asked to visit her. He is convinced her ill will may have caused certain misfortunes, and he seems to believe that Ynefel’s arrival may deal with her. I am uneasy in his intention, but mindful of your request to allow him all former privileges, and considering that, indeed, things might be afoot in which my forbidding him might have consequences I cannot foresee, I provided Ynefel’s ring as a protection against her influence and trust that his power will not permit harm to your son. Priests inform me that she has remained quiet, though your son’s insistence that she bears responsibility for his difficulties continues to trouble me as I write. I hope that I have done wisely in granting this request, and I shall continue vigilant in her case.

In all matters Amefel remains staunch and earnest in service of Your Majesty and Ylesuin. Likewise we remain confident our brother lords round about will be ready, as before, to support Your Majesty by all efforts, including our attendance in court in Guelemara, no matter the season, if requested. In this our brother lords surely concur.

Amefel salutes you and the Bryaltine fathers hold you in their prayers, against all harm, in constant intercession…

So it went, the usual formula at the end, with unusual force, considering. If he himself had leaned to any sect, it had been to the Teranthines, the sect of wizards, which had few rites, nineteen gods, a great deal of study, and not a single other adherent within all Amefel, that he knew. His hand felt naked without the ring he had lent the boy, and he felt less aware of the world than he had been. He had been long on the edge of wizardry and sorcery, he had the latter hanging quite literally over his head, and the absence of that trinket and its perceptions ought to be a relief, but it was not.

And the boy—the boy, another Aswydd, and now claiming that name—

He cared nothing for his own title. He had had no ambitions to be duke of Amefel, or aetheling, that peculiar honor that was, in history and in legality, a kingship in its own right. Amefel had wished to be like Elwynor, which was independent under Ninévrisë; but Amefel had become, by bloody murder, more closely bound; the aethelings, the Aswydd house, however, had continued to rule… payment for a bit of treachery.

No, he hadn’t wanted the title. But he had a wife, and the children, and his boys, other Aswydds, might remotely be in danger, if Otter—now Elfwyn Aswydd—found adherents to put forth a claim to set him in that office. He had faith in Cefwyn Marhanen—to say that any Aswydd had faith in a Marhanen king was unprecedented; but he did, in the man, if not in the lineage. He had faith that this Marhanen king was very unlike the last two, the first of whom had slaughtered the last remnant of the Sihhë-lords in Amefel, namely Elfwyn Sihhë…

Cefwyn Marhanen had taken a most uncommon friend, and, after all but wiping out the Aswydd lineage, had set him in power, and saved Lady Tarien, and kept his own Aswydd bastard alive—at Tristen’s behest, true, but also because Cefwyn was a new thing in that bloody line—a Marhanen king who stuck at murder…

An Aswydd duke with a family to protect ought rightly to take precautions now, establish ties to Bryalt priests, who always had been uneasy under Cefwyn’s rule… find others who chafed under what were essentially fair laws and fair taxes: but what would that make him if he followed his own father’s course?

He found no course for himself but to stay loyal, and care for the king’s son, and hope to the gods he so frequently offended that events would not come sliding down on his head, or worse, on his wife’s and his children’s heads. He trusted Cefwyn. He trusted Tristen. And the young Marhanen prince—Aewyn—himself half-Syrillas, which was to say, of the house of the Regents of Elwynor—with a sister, now, who would someday sit on the Regent’s throne… Aewyn seemed apt to be a good boy.

Another tangle, Cefwyn having the current Regent as his queen, gathering the Aswydds into his house on the one side, and the Elwynim Regents on the other, the Marhanen king now bringing into his own bloodline even a little Sihhë lineage—

It might be frightening, for those who had learned to hate the bloody Marhanen as a matter of local faith. Frightening, too for the Quinaltines, who had learned to think of their faith as the king’s only faith—and also for the Bryaltines, who had gotten most of their wealth from Amefin and Elwynim folk greatly opposed to the Quinalt and the Marhanen.

Now a living Sihhë sat in Ynefel, the Regent slept with the Marhanen king, and the duke of Amefel had a half-Marhanen, half-Aswydd boy in his care who might one day overthrow him and dispossess his children.

But Crissand stayed faithful, all the same, knowing that when everything came together, when powers that slept moved again, the world would shake.

Gods, he had had misgivings when Cefwyn chose Festival as the time to bring his firstborn son out of rural obscurity. It had been bravely done, thoroughly in character for Cefwyn, who had all the best traits of the bloody Marhanen, courage and will, and a less favorable one—a tendency to do the very thing that would annoy his detractors the most, simply because it wouldvex them, and give him, perhaps, a chance to bring those forces into the open…

Well, the tactic might work in the field, and even work in politics with the Guelenfolk and the northern provinces, but it was damned dangerous where it regarded Aswydd blood, and forces that couldn’t be seen so readily, forces another Aswydd did recognize, right over his very head.

Dared he think the boy might be right, that that decision of the king to bring the boy to Guelessar had been Worked, and nudged, and moved, very quietly?

Dared he write an honest Aswydd opinion to the Marhanen king? You were bespelled once, into begetting the boy. Don’t do the things you find yourself tempted to do. Don’t corner an Aswydd in hot blood and Marhanen temper… we don’t go at things head-on. We never have. That woman is a prisoner, but she is still aware of her son.

He did add a postscriptum, but not that. He wrote: If you should decide to come to Amefel for any purpose, pray wait for Lord Tristen’s arrival here. Then questions can be asked and answers given.

Tristen, when he did stir forth, tended to a harbinger of troubles. But having Tristen here, whatever the attendant perils of his company, would make him feel ever so much safer.

v

IT WAS A DAMNED GREAT MESS, IN CEFWYN’S OPINION–THE WEATHER DELAYED the messages he hoped for, the Quinaltine fuss simmered on, and he had no word at all from Tristen by any means. He hoped his son had found a quiet place to winter over.

The secret business at the Quinaltine was at least proceeding under Efanor’s direction, the notion of building a new Quinaltine being still closely held in a very small circle, the Holy Father tending toward the pronouncement that the Quinaltine as a physical structure was not unalterable, that it was, with priestly blessing, able to be enlarged—that was the Holy Father’s current position: that they might enlarge the sanctuary forward and move the altar to what was now the front steps, which would make it larger than the Guelesfort itself, and, no, that would not happen… Cefwyn had decided thatmatter before ever it became a whisper on the wind. Efanor had informed the Holy Father, who was balking at utter abandonment of the sacred precinct, and on and on it went.

And he had a hearing to attend on the morrow, a most distasteful hearing, a rural squire dead under unprovable circumstances, six young girls being his sole issue. The eldest, aged twelve, and not particularly outspoken, was betrothed, since his death, to a neighbor and second cousin, Leismond, while the grieving widow had drowned in the same sinking boat, so the report was. The servants had allegedly made off with the household silver, neither servants nor silver being yet found. The fishermen on the estate, meanwhile, had no one seeing to their rights. The marriage document only wanted a royal seal, perfunctorily granted, ordinarily, but he liked nothing about it. Marriage with the girl sent the land to Leismond, who coveted a river access, and the fishery—Squire Widin’s death was in that case suspiciously ironic—and he suspected it just possible the twelve-year-old bride might likewise come to grief within a fortnight of her marriage. He could delay a royal permission until the girl reached majority: that was easy—but the estate was failing fast. He could take temporary lordship of the land, which bordered the royal hunting preserve, cast a number of peasants out of their homes, set up a pliable and seemingly foolish child as a royal ward, denying Leismond or putting him off indefinitely. But that meant the Crown paying out six attractive dowries, or the children forever on the eldest sister’s husband’s charity—and where was he to find a husband besides Leismond who wanted to take in five underage and penniless sisters-in-law? The girl, questioned, denied she had been coerced. Oh, no, no, Leismond had been kind and helped them. It all reeked to the heavens.

Gods, he hated cases like this one.

He found himself at that window again, where on a happier day he had looked down on his two sons at practice. The yard was deep in snow, now, and desolate. Aewyn moped about, attending his studies, and having pinned a large map of Amefel above his study desk. Aewyn had stopped his rebellion, finally, and admitted his new tutor was a decent fellow, and that learning history was a good thing. Aewyn had even, by way of apology, he supposed, given him a very nice copy of the Rules of Courtly Order, written in a young hand that had begun to have clerkly flourishes perhaps unbecoming in a future king.

It was such a sad compliance, where there had been such joyous skirting of the rules…

He looked down at snow-covered stones, and measured the depth by the degree to which the rosebush in the corner was buried: only its pruned top and heap of mulch was above the snow, which seemed at its thinnest, there. A great icicle hung down from the eave, and several predecessors had crashed below, in the cyclic warming and chill of previous days.

His breath made a fog on the window, a veil between him and the courtyard. And suddenly his vision centered on a disturbance in that fogged glass. A word appeared.

Come, it said. Just that. Come.

Chilling as the first warning, to caution… and what dared he do?

He wanted to rush downstairs on the next breath, call for his horse, and ride, unprepared and unheralded, but a king had obligations… his person to protect, for the kingdom’s sake; documents to sign, matters which had been most carefully negotiated; the fate of two children to decide, that case on which important things rested… not least Efanor’s question of the Quinaltine…

He looked twice more at the window glass, to be absolutely sure, before he wiped it out with his sleeve and left no record.

Tristen had his other son in hand. Tristen wanted him to come to Ynefel. That was what. But it wouldn’t be a matter of his son’s life and death, not with Tristen protecting him. So the urgency was a little less.

He labored through the next few hours, wishing he knew exactly what to do with the Quinaltine, knowing that a priestly fuss was bound to break out in all its fury, with Ninévrisë here with Efanor, and Ninévrisë the higher authority, a Bryaltine, an Elwynim, and the target of all discontent: that worried him most. She was due, when snowmelt came, to take Aemaryen to Elwynor, the baby to be presented to the Elwynim as their heir to the Regency, their Princess, the fulfillment of the Marhanen promise to that kingdom; and she could not delay that journey for her own people, even if she became embroiled in priestly politics on this side of the Lenúalim.

Best she go, now, ahead of time, rather than late: best Efanor sit in power over the priests without the controversy of an Elwynim queen. Efanor knew how to argue with the Holy Father: gifted with the power of the king’s commission, and his alliances as duke of Guelessar, he could make progress with the Holy Father, if the Holy Father had no one else with whom to politic.

He had to get Ninévrisë and her ladies on the road early, that was what.

Then he could go to Amefel and from there on to Ynefel, where he ached to be, at least for the season. The prospect was beyond attractive.

“A little snow never can daunt me,” was Ninévrisë’s answer when he told her his intent. “But why so sudden?”

“Tristen Sent,” he said. To her, he could tell the entire truth. “He has Otter in keeping. He wants me. And I have to go.”

“Aewyn will go into mourning if you don’t take him with you,” Ninévrisë said, and that was the truth. He had thought of sending Aewyn with her, but it was very much the truth… and very much better politics among Guelenfolk not to have his son and heir in Elwynor while his wife, the Regent of Elwynor, was presenting his sister to the Elwynim as their own treaty-promised possession.

“He could meet Tristen,” Ninévrisë said. “I should ever so much wish to go, myself… but the treaty—they expect us this spring.”

“I know.” They stood at the same window, which now had one smeared pane, and he took her in his arms and kissed her. He loved this woman. He loved her for her steady calm and her lightning wit; and now for finding a clear, smooth way to do in an organized way what had seemed so impossibly difficult before he broke the news to her. Of course she would go. Of course a winter trip would be a strenuous adventure, but this was a woman who’d ridden to war, managed a soldiers’ camp, and could wield a weapon without a qualm. A little snow didn’t daunt her, indeed, not even with an infant in arms.

“I love you,” he said.

“Flattery, flattery. You’ll leave Efanor to manage things?”

“He can do everything I would do. More, with the priests: he knows all their secrets. Only you stay safe.”

“You keep an eye on our son,” Ninévrisë said, straight to the heart of the matter, a warning with a mother’s understanding of their son’s habits and the possibilities in the venture.

“He is growing up,” he said, to reassure her. “He made me a copy of the Courtly Order, do you know? It looked like a clerk’s hand. He mopes, grievously. He reads, this winter. He hasn’t stolen a horse or run off to Amefel. It’s the other boy who did that.”

“What he did whenOtter was here—No, no, I don’t blame Otter at all. He’s a wild creature. He always will be, I fear, and no ill against him. Our son, on the other hand, needsto read and mope a bit. Kings have to do that.”

He rested his head against hers. It was a comfortable place to be. “Perhaps this one needs to do a little less of it. His penmanship is too good. I ache to be out there, Nevris. I ache to be in Ynefel.”

“And I, to tell the truth. I ache to be on the road, snow and all. We’ll have to conspire, and appoint a tryst.”

“Where?”

“In Henas’amef, at first bloom?”

His head came up. He looked at her. “That’s a long time for us to be away from court.”

“Time enough for Efanor to be thoroughly weary of petitions. Time enough for the Holy Father to know he can’t bluff Efanor.” Her fingers ran, warm and soft, over his brow, and a smile quirked her lips. “You’ve gotten a little worry line, love. Shed it before it sets. It doesn’t become you.”

He kissed the fingers in question. “In Henas’amef,” he said. “We’ll ride home together from there, at first bloom.”

“Crocuses in the muddy fields,” she said, “and standing puddles to drown a pony in. I love Amefel in the springtime.”

He laughed. Iron bands let go from about his heart, when he thought of those muddy roads, and Tristen, and a ride or two together with him, the way it had used to be. He would never convince Tristen to go hunting. They would just ride, and visit odd places, and let the boys tag along.

And Nevris would come. And they would ride where they liked and meet old friends.

His people would be jealous, him conspiring with the Elwynim Regent down in Amefel, all the lords’ politicking therefore obliged to be done in the Amefin court, which meant a long, long ride for the northern ones—that might, in fact, mean far fewer of the northern, more quarrelsome lords at court this season. They might not think their petitions quite that desperate.

The south, now: it would be more convenient for them. He might manage a meeting with Cevulirn and Sovrag as well as Crissand. It would be old times again, the way they had begun.

He went and broke the news to Idrys, who lifted a brow, and said, “Indeed, my lord king,” and shook his head before he went off to disarrange the Guard from its winter quarters.

He broke the news to Efanor at dinner, and Efanor gave a long, thoughtful sigh, and shook his head, and said, “I’ll send the thorny cases on to you, dear brother. A muddy ride will damp the petitioners’ ardor. But before you go riding off, write a decree to possess the tract I have in mind. I have a large space on the hill—one that could give us the building space we need.”

“Where, for the gods’ sake? Who’s died?”

“Grenden. The only burgher so situated, elderly, and rattling in that house of his.”

“You’ll have the authority.”

“Best this come from you. I have in mind to settle Lord Grenden on a portion of the royal lands, a new estate at Mynford. It’s terrible hunting there. New management and enforcement of the boundaries might improve it. But with it goes an elevation, to the honor of a new place at court, new arms. He’s lusted after nobility all his life. And at his age, a little sanctity might come welcome.”

Grenden. Grenden, was it, a rich man who had bought a vacant property on the hill, abode of a house perished in the war, a partisan of Ryssand’s, and in no favor. Old Grenden was always at court, in outdated finery, an object of gossip. “You know our grandfather would have found the man guilty of something and outright seized the old house.”

“Oh, aye, but Grenden’s old, he doesn’t hunt, and he has no issue. The estate will revert in a decade, or he’ll take my very kind advice and adopt Squire Widin’s six girls.”

“Oh, I do like that,” Cefwyn said. “The cousin goes begging. And the new lord Mynford gets Widin’s holdings, with the fisheries and the farms across the river, no need to clear the deep woods. An ample dowry… safety for the girls. A posterity for poor old Grenden.”

“See? So simply solved. The old trees at Mynford stand, the deer increase, we have the hilltop grounds for the Holy Father—he doesn’t think it can be done—and we get Widin’s orphans out of the hands of Leismond.”

“Brother, you have my utmost confidence.”

Efanor smiled, his shy, true smile, not the one he showed ordinarily. “I win my case?”

“You win it. I’ll sign your decree. You have the spring court, all your own. I’m for Amefel.”

“I do miss him,” Efanor said. “Give him my regards. And Crissand, too. Tell Crissand I shall be riding by, when you come back. I’ll be due a rest of my own, by then.”

“Done,” he said. “And you’ll have every right.”

Packing went apace, then. He requested Ninévrisë entrust Aemaryen to the nurse for the night. They spent the early evening dining alone by the fire, and the later evening as lovers. They still were, after bringing two children in the world: missing Nevris was the only sorrowful part of the trip.

In the morning, having summoned Aewyn for breakfast, he broke the not-unwelcome news.

“I take it,” he said, “that you would gladly miss your history lessons in favor of a small trip outdoors.”

“I’ve done my lessons,” Aewyn said, frowning, his defenses up. “My tutor can’t say I haven’t.”

“So you might like to ride to Amefel.”

“To Amefel!” The sluggard who had shared their table so glumly for days vanished, transformed and bright-eyed—though warily asking, “Might I? Truly?”

“Your brother has slipped off again, in directions not prudent. I think I may ride that way. You might stay with Gran for a few days, if he isn’t there, while I go looking for your brother.”

“I can find him,” Aewyn said, all too pertly. “I have no doubt I can find him.”

He let that pass for the moment. “Go pack,” he said to his son. “Take clothes, no trinkets, and nothing heavy. Do it yourself. Think of it as a hunting trip and a court visit.”

And when his son had left a half-eaten breakfast and walked from the room, half-running, he got up and set his hand on his wife’s.

“Dared you think he would be reluctant, my lord?” Ninévrisë asked him.

“Take care of our daughter,” he asked her, “and of yourself.”

“Take care of our son,” Ninévrisë said. Her hand closed on his. “How will you explain this venture to the court? Have you thought of that?”

“Why, there’s a letter from Crissand. A pressing matter. Letters have flown back and forth like snowflakes. Everyone knows it.” He kissed her cheek. “And I leave Idrys to support Efanor.”

“Dare you?”

“He will obey Efanor,” he said, devoutly hoping that was the case. His departure did remove a certain restraint he imposed on his Commander of the Guard—but Idrys would indeed support Efanor and protect him from his charitable impulses, if not meticulously obey him. He need not fear for Efanor’s life, at very least.

And, uncommon for royal processions, by midmorning he was already on horseback, with his son, a fair company of the Dragon Guard, and a smallish pack train, mostly carrying clothes and three tents. They would sleep under canvas—he wished to give Aewyn the experience of a winter camp—and delay as little as possible along the route. Ninévrisë, with far more baggage and a train of ladies, purposed to depart the capital in two days, and cross northerly into Elwynor. As for the weather, it blew hard for an hour, then spat snow into their faces the moment they passed the city gates.

It was a gray day, windy and biting cold, but his son’s face was bright. So, he suspected, was his own.

CHAPTER FIVE

i

THE RING TINGLED AT TIMES. SIHHË-WORK, GRAN HAD CALLED IT, BUT WHETHER she meant the ring itself or the spell on it, she declined to say. She refused to touch it, herself, saying it would burn the hand that tried to take it, until it went back to its master. Paisi, whose eyes were better, said it looked like a pledge ring from the town market, with its little design of vines and grapes, not outstandingly well made, but silver. Sihhë-work in silver, Paisi said, was much better made.

The ring gave him one night’s sound sleep, at least. But he waked in the memory of freezing in the woods, and of losing Owl, and then of coming home to Gran’s and finding the place all burned.

He waked with such a start he thought surely he must have waked Paisi, but Paisi snored on, and he lay in the dark, sweating and seeing horrors in the common shadows of the room. The fire in the fireplace seemed like a beast caged and trying to break free, and the ring on his finger was cold as ice.

The horror stayed with him. He hardly dared shut his eyes, and when he did, he had to drag himself out of the same horrid dream, in which he wandered among burned timbers and fallen beams. “Gran,” he cried, and no one answered him.