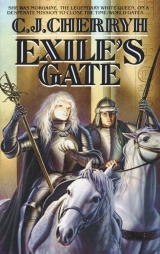

Текст книги "Exile's Gate "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

He dared not use it now, in any hope of warning her. He had given his sword to Chei and not reclaimed it—not, in all else they had done, turned him out utterly defenseless.

He had no weapon now but his bow.

And Heaven knew how far he was behind.

He listened as he rode the center of the stream, close to their camp. He stopped Arrhan where there was brush enough to hide her, and slid down, and stood for a moment steadying her so that he could hear the least stirring of the wind.

A bird sang, natural, long-running song, but it was not a sound that reassured him. There were the tracks, evident now at this muddy bank, and hours old.

Now it was a hard choice what to do. There was no safe place further than this. He took one risk, and made a faint, careful birdcall: I am here, that said, no more than that.

No answer came to him.

He bit his lip furiously, and put a secure tie on Arrhan, took his bow and quiver and slipped away into the brush, onto the hillside. He was not afraid, not yet. There were too many answers. There was every chance she had heard him and dared not risk an answer.

He went hunter-fashion, stopping often to listen. He found the tracks again where he picked up the stream course; and when he had come within sight of the place where they had camped, beneath the hill, Siptah was gone, and with one glance he was reassured.

Good, he thought, she has taken him, the tack is gone.

But there were marks of the enemy's horses, abundant there, trampling on Siptah's and Arrhan's marks, and no matter the skill of the rider, there was no way not to leave some manner of a trail for a good tracker well sure where that trail began.

She would lead them, that was what she would do. She would lead them around this hill and that until they came straight into one of her ambushes.

But so many riders had gone awayfrom this point, left and right, obliterating any tracks the gray stud might have made, the tracks they could have followed; and left him the necessity to cast about beyond the trampled area—and cast about widely he could not, without risking ambush.

Best, he thought, find out what was still here.

He moved, crouched behind what cover there was, along the flank of the hill, among the rocks, stopping now and again to listen. There was nothing astir but the wind.

Then a bird flew up, taking wing east of his backtrail.

He froze where he was, a long time, shifting only the minuscule degree that kept his legs from cramping.

A birdcall sounded, directly on his track.

He calmly, carefully scanned the hillsides and the points of concealment so far as he could from his own cover, not willing to give way to any feeling, not fear, not self-reproach for anything he might have done and not done: there was only the immediate necessity to get off this hillside and take the enemy, whatever had happened behind him, else he might never find her.

He waited what he judged long enough to make them impatient, then moved, quietly, behind what cover the brush and the rocks afforded, without retracing his steps into what might now be tracking him.

They meant him to go to his horse. They had found Arrhan, that was what had happened, and they were effectively advising him where the ambush was, and where he had to go, if he did not want to flee them afoot.

Where is she? was his constant thought. The whole area had become hostile ground, enemy marks everywhere, his horse discovered, and no sign of Morgaine.

If she had heard the birdcalls, she was at least warned.

He sank down behind a rock to wait a moment, to see what they would do, and there was not a sound, not a stir below.

Not even the wind breathed.

Then a pebble rolled, somewhere on the bare rock around the shoulder of the hill above him. A step whispered across stone and left it again.

Carefully he took three arrows from his quiver and fitted one to the string, braced himself comfortably and waited with the bow unbent, not to cramp his arm, for one quick shot if need be.

The step came closer and the sweat ran on his brow and down his sides, one prickling trail and another.

The sound stopped a moment, then advanced again, a man walking on the rock a moment, then disturbing the brush.

He drew a breath and bent the bow all in one motion.

And held his shot in a further intake of breath as a man in a bright mail shirt saw him and slid down the crumbling hill face. His bow tracked the target.

"Vanye," Chei breathed, landing on two feet in front of him. "For God's sake—I followed you. I havebeen following you. What did you expect when you told me go back? Put that down!"

"Where is she?"

"Gone. Put down the bow. Vanye—for God's sake—I saw them pass; I followed them. There was nothing I could do—"

"Where is she?"

"Northward. That is where they will have taken her."

His heart went to ice. He kept the bow aimed, desperate, and motioned with it. "Clear my path."

"Will you kill me too?" Chei's eyes were wide and outraged. "Is that what you do with your friends?"

"Out of my way."

"Your friends,Vanye," Chei repeated, and flattened himself against the rock as he edged past. "Do you know the word? Vanye!"

He turned from Chei to the way ahead, to run, remembering even then the whistle he had heard downslope; and saw an archer standing in his path as a weight smashed down between his shoulders and staggered him.

He rolled, straight down the hillside, tucked his shoulder in a painful tangle of armor straps and bow and quiver. His helm came off; he lost the bow; and went upended and down again on the grass of the slope.

He came up blind, and ripped his Honor-blade from its sheath, hearing the running steps and the rattle of armor, seeing a haze of figures gathering about him on the hillside, above and below him.

"Take him alive!" someone shouted. "Move!"

He yelled out at them and chose a target and a way out, cut at a qhal who missed his defense, met him with a shock of steel against leather and flesh; but in that stroke his foot skidded on the bloody grass and there was another enemy on him, with more coming. He recovered his balance on both feet and laid about him with a clear-minded choice of threats, finding the rhythm of their attacks and their hesitations for a moment; and then losing it as other attackers swarmed in at another angle.

A man, falling, seized him by the leg. He staggered and others hit him and wrapped a hold about him, inside his guard; and overbalanced him and bore him down in a skidding mass of bodies.

They brought up against a rock together. It jolted the men who held him and he smashed an elbow into one body and a fist into another's head as he struggled free and levered himself toward his feet, staggering against the tilted surface as he tried to clear his knife hand of the dazed man who clung to it.

Steps rushed on him, a shadow loomed out of the sun at his right, and others hit him, carrying him backward against the rock. The point of a sword pressed beneath his chin and forced his head back.

Chei's face cleared out of the haze and the glare, Chei's face with a grin like the wolves themselves, and a half a score of qhalur and human faces behind him.

"Ah," Chei said, "very close, friend. But not good enough."

Chapter Thirteen

They flung him down on the trampled ground of the streamside, and he did not know for a moment where he was, except it was Chei sitting cross-legged on the grass, and Chei's face was a mask behind which lived something altogether foreign.

Chei was dead, as Bron was dead. He knew it now. As many of these men's comrades were dead, several wounded, and he was left alone with them to pay for it. That was the logic he understood. It was not an unreasonable attitude in men or qhal, not unreasonable what they had done in the heat of their anger, with a man who had cost them three dead on the selfsame hillside.

Not unreasonable that Chei should look on him now as he did, coldly—if it were Chei and Chei's reasons. But it was not. He was among men who fed their enemies to beasts.

Morgaine, he thanked Heaven, had ridden clear. She had escaped them, he was sure of it. She had ridden out, she was free out there, and armed with all her weapons.

She might well be anywhere in the country round about. Heaven knew, the same stream that had covered his tracks could cover hers—in the opposite direction, he thought; toward the Road; which their enemies must have thought of, and searched, and failed.

She might have fled toward the north and east as the Road led, thinking to find him by cutting into the country along the way; but that was so remote a chance. Gone on to the Gate itself . . . that was possible; but he did not think so: she would not ride off and leave him to fall into ambush.

Unless...O God, unless she were wounded, and had no choice.

And he did not reckon he would have the truth from these men by asking for it.

"Why are you here?" Chei asked him, as if he had a list of questions in mind and any of them would do. " Where do you come from? Where are you going?"

They had not so much as bound him. It was hard enough to lift his cheek from the mire and regard Chei through whatever was running into his eyes and blurring his vision.

"She has authority to be here," he said, which he reckoned for the truth, and perhaps enough to daunt a qhal.

"Are you full human?"

He nodded and shifted his position, and whatever was dripping, started down his cheek. He dragged his arms under him, and felt, beneath the mail and leather, the pressure of the little box against his heart. They had not discovered it. He prayed Heaven they would not, though they had taken his other weapons, from Honor-blade to boot knife. And the arrhendur sword in Chei's lap he well remembered.

"Is she qhal?"

He had answered that so often he had lied before he realized it, a nod of his head. "Aye."

"Are you her lover?"

He did not believe he had heard that question. He was outraged. Then he knew it was one most dangerous to him. And that Chei in Chei's own mind—had his own opinion. "No," he said. "I am her servant."

"Who gave her that weapon?"

"Its maker. Dead now. In my homeland." His arms trembled under him. It was the cold of the ground and the shock of injury. Perhaps also it was fear. There was enough cause for that. "Long ago—" he began, taking breath against the pain in his gut. "Something happened with the gates. It is still happening—somewhere, she says. Against that, the sword was made. Against that—"

"Bring that thing near a gate, Man, and there will bedeath enough."

He started to agree. Then it came to him that they seemed to know—at what range from a gate the sword was too perilous to use. And that put Morgaine in danger.

"What does she seek in Mante?"

The tremors reached his shoulders, tensed his gut so that the pain went inward, and he wished, for his pride's sake, he could only prevent the shaking from his voice.

"What does she seek in Mante?"

"What she would have sought in Morund," he said, "if we had not had other advice."

Chei? he wondered, gazing into that face. Chei? Is there anything left?

Can you remember, man? Is there anything human?

"What advice would that be?"

"That you were unreasonable. Chei knows." He heaved himself upward another hand's-breadth to ease the pain in his hip, where they had kicked him, and the tendon there was bruised. He determined to sit up and risk a cracked skull from the ones behind him; and discovered that there was no part of him that their kicks or the butts of their lances had not gotten to. It was blood running down his face. It splashed dark onto his leg when he sat up, and he wiped at the cut on his brow with a muddy hand. "My lady's mission here—you very well know."

"Death," Chei said, "ultimate death—for every qhal."

"She intends no harm to you—"

"Death."

It seemed the sum of things. There was no peace, then, once the qhal-lords knew what Morgaine purposed with the gates. He gazed bleakly at Chei, and said nothing.

"Where will your lady have gone?"

"To Mante."

"No," Chei said quietly. "I doubt that she has. I remember,friend. I remember a night in Arunden's camp—you and she together—do you recollect that?"

He did. There was altogether too much Chei knew; and he despaired now of all the rest.

"I rather imagine," Chei said, "that your lady is somewhere in these hills. I rather imagine that she would have tried to warn you—if she could reach you in time. Failing that—she will follow if we move. If we were foolish enough to kill you, then she might even come looking for revenge—would she not?"

"I do not know," he said. "She might well have ridden for Mante."

"I do not think so," Chei said. "I think she is waiting for dark."

He said nothing. He tensed muscles, testing whether he could rely on his legs if he made a lunge for Chei's throat. To kill this man might at least keep some knowledge out of the hands of the qhal.

It might put some enemy less dangerous in command of this band, at least.

"I think," Chei said, "she will come close to see whether you are alive. Afoot, by stealth. And perhaps for your sake she might come and talk to us a little closer."

"Set me free," Vanye said. "I will find her and give her whatever message you wish. And come back to you."

There was startled laughter.

"I am Kurshin," Vanye said. "I do not break an oath."

Chei regarded him in silence a long time, eyes flickering slowly, curiously, as if he might be reaching deep into something not qhal and not familiar to him. The laughter died away.

"Chei?" Vanye said, ever so quietly, seeking after whatever balance might have shifted.

"Possibly that is so," Chei said then, blinking. "I would not say that it is not. But who knows what you would bring back? No. She will come in for you. All you have to do is cry out—and you can do that with no persuasion, or with whatever persuasion it—"

He sprang, sliding in the mud, for Chei's throat; and everyone moved, Chei scrambling backward, the men around them moving to stop him. Chei fended his first hold off and he grabbed Chei's shirt and drove a hand toward Chei's throat to break it, but hands dragged at him, and the blow lost force as they bore him under a tide of bodies and against the edge of the rock.

There were more blows. He protected himself as he could and the armor saved him some of it. He hoped that he had broken Chei's neck and saved them all from the damage Chei might do—but it was a small hope, dashed when they hauled him up by the hair and Chei looked down at him from the vantage of the rock, smiling a twisted, bloodied smile.

"—with whatever persuasion it takes," Chei said.

"She is not a fool."

"—so she will know you are with us. If she comes in—she will have some care of that fact. Will she not?"

"She is not a fool."

"A fool would kill his hostage. Keep thinking of that." He made another lunge, while he had the chance. They stopped him. They battered him to the ground and held him there while they worked at his buckles and belts, and when he fought them they put a strap around his neck and cut off his wind.

It was a man of considerable temper, Chei observed, probing with his tongue at the split in his lip: a lunatic temper, a rage that did damage as long as he could free a hand or a knee. But this was the man had wielded the gate-sword. This was the man had taken half his house guard and the most part of the levies.

Another image came to him—a chain was on his leg, and this wild man came riding down on the wolves, leaning from the white horse's saddle to wield his sword like some avenging angel, bloody in the twilight.

This same man, bowing the head to his liege's tempers—defending him with quiet words, glances from under the brow, measured deference like some high councillor with a queen—

They had him down, now, having finally discovered there was no way to deal with him without choking him senseless. "Do not kill him!" Chei shouted out, and rose from his seat on the rock and walked the muddy ground to better vantage over the situation.

They stripped him—he was very pale except his face and hands, a man who lived his life in armor. Armor lying beside the little stream—armor lying beside a river—the same man offering medicines and comfort to him—

"My lord," someone said, and asked a question. Chei blinked again, feeling dizzied and strangely absent from what they did, as if he were only spectator, not participant.

"Do what you like," he murmured to a question regarding the prisoner; he did not care to focus on it. He remembered his anger. And the dead, Jestryn-Bron. And the sight of his men vanishing into gate-spawned chaos.

It was the woman he wanted within his reach. It was the sword, against which there was no power in Mante could withstand him—the woman with her skills, and himself with a valued hostage. There was—a thought so fantastical it dizzied him—power over Mante itself, a true chance at what they had never dared aim for.

He retired to the rock, sat down, felt its weathered texture beneath his right hand. He heard commotion from his men, glanced that way with half attention. "Let him alone," he said to the man who hovered near him. "The man will not last till Mante if you go on, and then what hostage have we against the gate-weapons? Twilight. Twilight is soon enough."

It was as if the strength the gate had lent him had begun to dissipate. He heard voices at a distance. He saw them drag their captive up against one of two fair-sized trees at the edge of the brush, along the stream, saw him kick at one of them, and take a blow in return.

"Stubborn man," he murmured with a pain about him that might be Jestryn and might be Bron and might be outrage that this man he had trusted had not prevented all the ill that had befallen him.

Or it was pointless melancholy. Sometimes a man newly Changed wept for no cause. Sometimes one grew irrationally angry, at others felt resentments against oneself. It was the scattered memories of the previous tenant, attempting to find place with the new, which had destroyed it.

He had fought this battle before. He knew coldly and calmly what was happening to him, and how to deal with it—how he must to deal with the memories that tried to reorganize themselves, for his heart sped and his body broke out in sweat, and he saw the wolves, the wolves that ep Kantory mustered like demons out of the dark; he heard the breaking of bones and the mutter of wolfish voices as he walked across the trampled ground, to where his men had managed finally to bind the prisoner's hands about the tree.

"Chei—" Vanye said, looking up at him through the blood and the mud. And stirred a memory of a riverbank, and kindness done. It ached. It summoned other memories of the man, other kindnesses, gifts given, defense of him; and murder—Bron's face. "Chei. Sit. Talk with me. I will tell you anything you ask."

Fear touched him. He knew the trap in that. "Ah," he said, and sank down all the same, resting his arms across his knees. "What will you tell me? What have you to trade?"

"What do you want?"

"So you will offer me—what? The lady's fickle favor? I went hunting Gault, friend.That is what you left me. And I am so much the wiser for it. I should thank you."

"Chei—"

"I went of my own accord. We discovered things in common. What should I, follow after you till you served me as you served Bron? I was welcome enough with your enemies."

Vanye flinched. But: "Chei," he said reasonably, "Chei—" As if he were talking to a child.

"I will send you to Hell, Vanye. Where you sent Bron."

Vanye's eyes set on his in dismay.

"I say that I was willing. Better to bea wolf, than to be the deer. That is what you taught me, friend.The boy is older, the boycannot be cozened, the boyknows how you lied to him, and how you despised him. Never mind the face, friend:I am much, much wiser than the boy you lied to."

"There was no lie. I swear, Chei. On my soul.– For God's sake, fight him, Chei– Did you never mean to fight him?"

Chei snatched his knife from its sheath and jerked the man's head back by the braid he wore, held him so, till breath came hard and the muscles that kept the neck from breaking began to weaken. The man's eyes were shut; he made no struggle except the instinctive one, quiet now.

"No more words? No more advice? Are you finished, Man? Eh?"

There was no answer.

Chei jerked again and cut across the braid, flung it on the ground.

The man recovered his breath then in a kind of shock, threw his head back with a crack against the tree and looked at him as if he had taken some mortal wound.

It was a man's vanity, in the hills. It was more than that, to this Man. It was a chance stroke, and a satisfaction, that put distress on that sullen face and a crack in that stubborn pride.

Chei sheathed the knife and smiled at human outrage and human frailty and walked away from it.

Afterward, he saw the man with his head bowed, his shorn hair fallen about his face. Perhaps it was the pain of his bruises reached him finally, in the long wait till dark, and his joints stiffened.

But something seemed to have gone from him, all the same.

By sundown he might well be disposed to trade a great deal—to betray his lover, among other things: the first smell of the iron would come very different to a man already shaken; and that was the beginning of payments ... his pride, his honor, his lover, his life; and the acquisition of all the weapons the lady held.

Always, Qhiverin insisted, more than one purpose, in any undertaking: it was that sober sense restrained him, where Chei's darkness prevailed: revenge might be better than profit; but profitable revenge was best of all.

And there were those in Mante who would join him, even yet. . . .

Unease suddenly flared in the air, like the opening of a gate. A man of his cried out, and dropped something amid the man's scattered belongings down along the streamside, a mote that shone like a star.

"Do not touch it!" Chei sprang up and strode to the site at the same time as the captain from Mante, and was before him, gathering up that jewel which had fallen before his own man could be a fool and reach for it again—a stone not large enough to harm the bare hand, not here, this far from Mante and Tejhos: but it prickled the hairs at his nape and lit the edges of his fingers in red.

And there was raw fear in the look of the man who had found it.

"My lord," the captain objected. There was fear there, too. Alarm. That is not for the likes of you,was what the captain would say if he dared.

But to a lord of Mante, even an exiled one, the captain dared not say that.

Chei stooped and picked up the tiny box which his startled man had dropped amid Vanye's other belongings, and shut the jewel in it. Storm-sense left the air like the lifting of a weight. "I will deliver this," Chei said, staring at the captain. His own voice seemed far away in his ears. He dropped the chain over his head. "Who else should handle it? I still outrank you,—captain."

The captain said nothing, only stood there with a troubled look.

This, a Man had carried. The answering muddle of thoughts rang like discord, for part of him was human, and part of him despised the breed. That inner noise was the price of immortality. The very old became more and more dilute in humankind: many went mad.

Except the high lord condemned some qhal to bear some favorite of his—damning some rebel against his power, to host a very old and very complex mind, well able to subdue even a qhalur host and sift away all his memories.

From that damnation, at least, his friends at court had saved him, when he had given up Qhiverin's pure blood and Qhiverin's wholly qhalur mind for Gault's, which memories were there too—mostly those which had loved Jestryn when Jestryn was human. And knowledge of the land, and of Gault's allies—and Gault's victims—when Gault was human: but those were fading, as unused memory would.

There were a few things worth saving from that mind, things like the knowledge of Morund's halls and the chance remembrance of sun and a window, a knowledge that, for instance, Ithond's fields produced annually five baskets of grain—some memories so crossed with his own experience at Morund that he was not sure whether they were Gault's recollections or his own.

Gault's war was over. He no longer asserted himself. It was the Chei-self, ironically, which had done it—human and forceful and flowing like water along well-cut channels: young, and uncertain of himself, and willing to take an older memory for the sake of the assurance it offered, whose superstition and doubts scattered and faded in the short shrift the Qhiverin-essence made of it: wrong, wrong, and wrong, the Qhiverin-thoughts said when Chei tried to be afraid of the stone he held. Let us not be a fool, boy.

This is power– and the captain has to respect it; and very much wishes he had Mante to consult. And what I can do with it and with what the lady carries, you do not imagine.

"Place your men," he ordered the captain.

"My lord," the man said. Typthyn was his name.

The serpent's man. Skarrin's personal spy.

Chei drew a long breath through his nostrils and looked at the sky, in which the sun had only then passed zenith.

The sun went down over the hill, the shadow came, and they built a fire, careless of the smoke. Vanye watched all this, these slow events within the long misery of frozen joints and swollen fingers. He had not achieved unconsciousness in the afternoon. He had wished to. He wished to now, or soon after they began with him, and he was not sure which would hurt the worse, the burning or the strain any flinching would put on his joints.

He flexed his shoulders such as he could, and moved his legs and arched his spine, slowly, once and twice, to have as much strength in his muscles as he could muster.

In the chance she might come, in the chance his liege, being both wise and clever, might accomplish a miracle, and take this camp, and somehow avoid killing him, remembering—he prayed Heaven—that there was a gate-stone loose and in the hands of an enemy.

But if that miracle happened, and if he survived, then he would have to be able to get on his feet. Then he had to go with her and not slow her down, because there was no doubt there were forces coming south out of Mante, and he must not, somehow must not, hinder her and force her to seek shelter in these too-naked hills, caring for a crippled partner.

A partner fool enough to have brought himself to this.

That was the thing that gnawed at him more than any other—which course he should take, whether he should do everything the enemy wished of him and trust his liege to stay clear-headed; or whether he should refuse for fear she would not, and then be maimed and a burden to her if she did somehow get to him.

Then there was that other thought, coldly reasonable, that love was not enough for her, against what she served. There had been some man before him. And she traveled light, and did always the sensible thing—no need ever fear that she would do something foolish.

He told himself that: he could do what he liked, cry out or remain silent, and have the qhal dice him up piecemeal, and it would do neither harm nor good. He had been on his own since she rode out of here, and would be, till the qhal dragged him as far as Mante and either killed him or, more likely, treated his wounds and kept him very gently till some qhal claimed him for his own use.

Or—it was an occasional thought, one he banished with furious insistence—she might have run straight into forces sent from Mante, and be pinned down and unable to come back—or worse; or very much worse. A harried mind conjured all sorts of nightmares, in the real and present one of the smell of smoke and the unpleasant, nervous laughter of men contemplating another man's slow destruction.

The darkness grew to dusk. The qhal finished their supper, and talked among themselves.

When Chei came to him, to stand over him in the shadows and ask him whether he had any inclination to do what they wanted.

"I will call out to her," Vanye said, not saying what he would call out, once he should see her. "Only I doubt she is here to listen. She is well on her way down the road, that is where she is."

"I doubt that." Chei dropped down to his heels, and took off the pyx that swung from its chain about his neck. "Your property."

He said nothing to that baiting.

"So you will call out to her," Chei said. "Do it now. Ask her to come to the edge of camp—only to talk with us."

He looked at Chei. Of a sudden his breath seemed too little to do what Chei asked, the silence of the hills too great.

"Do it," Chei urged him.

He shaped a cut lip as best he could and whistled, once and piercingly. "Liyo!"

And with a thought not sudden, but one that had come to him in the long afternoon: "Morgaine, Morgaine!For God's sake hear me! They want to talk with you!"

"That is not enough," Chei said, and opened the box, so that a light shone up on his face from the gate-jewel there. The light glared; flesh crawled. Everything about it was excessive and twisted.

"You have only to feel that thing," Vanye said, "to know there is something wrong in the gate at Mante. Truth, man. I have felt others. I know when one is wrong."

"You– know."

"You have no right one to compare it against. It is wrong. It is pouring force out—" He lost his thought as Chei took the jewel in his fingers and laid it down again in the box, and set the open box on the ground beside him.

"So she will know where you are. Call to her again."

"If she is there, she heard me." He had hope of that small box and its stone. The light that made him visible in the twilight, made Chei a target, if Morgaine were there, if she could be sure enough whether the man kneeling by him was the one she wanted. She might be very accurate—unlike a bowman. Several men might be on their way to the ground before they knew they were under attack.

Or she might, instead, be far on her way to Mante.

"That is not enough," Chei said, and called to the men at the fire in rising. "You can," he said then, looking down, "give her far more reason."