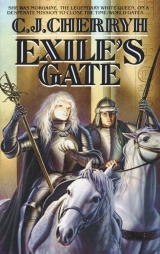

Текст книги "Exile's Gate "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

"Chei."

"Chei." Vanye rose and took his arm, and pulled the man up to take his weight on his left foot, steadying him as he tried the right. "Mine is Vanye. Nhi Vanye i Chya, but Vanye is enough outside hold and hall. There. Walk down to the water. I warn you it is cold. I would have heaved you in last night, with that gear of yours, except for that. Go on. I will find you down by the water. I willfind you down by the water—or I will findyou. Do you hear me?"

Thoughts of escape passed through the man's head, it was clear by the wariness in his eyes; then different thoughts entirely, and fear, the man being evidently no fool. But Vanye walked away from him, going back after his kit by the fire.

"Be careful with him!" Morgaine said sharply, as he bent down near her. Hereyes were on the prisoner. But he had been sure of that when he had turned his back.

Vanye shrugged and sank down a moment to meet her eyes. "Do as I see fit, you said."

"Do not make gestures."

He drew a long breath. So she set him free and then wanted to pull the jesses. It was not her wont, and it vexed him. But clearly she was worried by something. "Liyo,I am not in danger of a man lame in one foot, smaller than I am and starved into the bargain. Not in plain daylight. And I trust your eye is still on him—"

"And we do not know this land," she hissed. "We do not know what resources he may have."

"None of them came to him on that hilltop."

"Thee is leaving things to chance! There are possibilities neither of us can foresee in a foreign place. We do not know what he is."

Her vehemence put doubt into him. He bit his lip and got up again. He had never quite let his own eye leave the man in his walk downhill, save the moment it took to reach her; but it seemed quibbling to protest that point, the more so that she had already questioned his judgment, and justly so, last night. Beyond this it came to opinion; and there were times to argue with Morgaine. The time that they had a prisoner loose was not that moment.

"Aye," he said quietly. "But I will attend him. I will stay in your sight. As long as you see me, everything is well enough."

He gathered up one of their blankets for drying in, along with his personal kit. He walked down the hill, pausing on the way to lay a hand on Siptah's shoulder, where the big gray and white Arrhan grazed at picket on the grassy slope. He reckoned that Morgaine would have that small black weapon in hand and one eye on him constantly.

It was not honorable, perhaps, to deal with hidden weapons in the pretense of being magnanimous; but Morgaine—she had said it—did not take pointless chances. It was not honorable either, to tempt a frightened man to escape, to test his intentions, where keeping him under close guard would save his life. And other lives, it might well be.

But the man had not strayed—had attended his call of nature and limped his way down to water's edge by the time Vanye had walked the distance downslope, and he had never dared bolt from sight of them or wander behind branches. That much was encouraging. Chei had bent down to drink, with movements small and painful, there on the margin.

"Wash," Vanye said, and dropped the folded blanket beside him on the grass. "I will sit here, patient as you like."

Chei said nothing. He only sat down, bowed his head and began with clumsy efforts to unbuckle straps and work his way out of the filth-and weather-stiffened leather and mail, piece after piece of the oddly fashioned gear laid aside on the bank.

"Lord in Heaven," Vanye murmured then, sickened at what he saw—not least was he affected by the quiet of the man sitting there on the grass and taking full account, with trembling hands and tight-clamped jaw and a kind of panic about his eyes, what toll his ordeal had taken of his body—great, deep sores long festered and worn deep in his flesh. Wherever the armor had been ill-fitted, there infection and poison had set in and corruption had followed, deepening the sores, to be galled again by the armor. Wherever small wounds had been, even what might have been insect bites, they had festered; and as Chei pulled the padding beneath the mail free, small bits of skin and corruption came with it.

It was not the condition of a man confined a day or even a few days. It bespoke something much more terrible than he had understood had happened on that hill, and the man sat there, trembling in deep shock, trying stolidly to deal with what a chirurgeon or a priest should attend.

"Man—" Vanye said, rising and coming over to him. "I will help."

But the man turned his shoulder and wanted, by that gesture, no enemy's hands on him, Vanye reckoned—perhaps for fear of roughness; perhaps his customs forbade some stranger touching him; Heaven knew. Vanye sank down on his heels, arms on his knees, and bit his lip for self-restraint, the while Chei continued, with the movements of some aged man, to peel the leather breeches off, now and again pausing, seeming overwhelmed by pain as if he could not bear the next. Then he would begin again.

And there was nothing more than that, that a man could do, while Vanye watched, flinching in sympathy—Lord, in Ra-morij of his birth, a gentleman would not countenance this sort of thing—chirurgeon's business, one would murmur, and cover his nose and go absolve himself with a cup of wine and the noisy talk of other men in hall. He had never had a strong stomach with wounds gone bad.

But the man doggedly, patiently, worked out of the last of it, put his right leg down into the water, and the left, and slipped off the bank, to lose his balance and fall so suddenly that Vanye moved for the edge thinking he had gone into some hole.

Chei righted himself and clawed for the bank—held on in water only chest deep as Vanye gripped his forearm against the grass. Chei was spitting water and gasping after air, his blond hair and beard streaming water, his teeth chattering in what seemed more shock than cold.

"I will pull you out," Vanye said.

"No," Chei said, pulling away. "No." He slipped again, and all but went under, fighting his way to balance again, shivering and trying to pull free.

Vanye let him go, and watched anxiously as the prisoner ducked his head deliberately and rubbed at ingrained dirt, scrubbing at galled shoulders and arms and body.

Vanye delved into his kit and found the cloth-wrapped soap. "Here," he said, offering it out over the water. "Soap."

The man made a few careful steps back to take it and the cloth; and wet it and scrubbed. The lines about the eyes had vanished, washed away with the dirt. It was a younger face now; tanned face and neck and hands, white flesh elsewhere, in which ribs and shoulder-blades stood out plainly.

More of scrubbing, while small chains of bubbles made serpentines down the rapid current. There was danger of that being seen downstream. But there was danger of everything—in this place, in all this unknown world.

"Come on," Vanye said at last, seeing how Chei's lips had gone blue. "Come on, man—Chei. Let me help you out. Come on,man."

For a moment he did not think the man could make it. Chei moved slowly, arms against his body, movements slowed as if each one had to be planned. The hand that grasped Vanye's was cold as death. The other carefully, deliberately, laid the soap and the cloth in the grass.

Vanye pulled on him, wet skin slipping in his fingers, got the second hand and drew him up onto the grass, where Chei might have been content to lie. But he hauled Chei up again and drew him stumbling as far as the blanket, where he let him down on his side and quickly wrapped him against the chill of the wind, head to foot.

"There," Vanye said. "There—stay still." He hastened up again, seeing Morgaine standing halfway down the slope, there by the horses: and recalled a broken promise. He hadleft her sight. He was shamefaced a second time as he walked up to speak to her.

"What is wrong?" she asked, fending off Arrhan's search for tidbits. There was a frown on her face, not for the horse.

He had turned his back on their prisoner again. But: "He is too ill to run," Vanye said. "Heaven knows—" It was not news that would please her. "He is in no condition to ride—No, do not go down there, this is something a man should see to. But I will need the other blanket. And my saddlebags."

She gave him a distressed look, but she stopped with only a glance toward the man on the bank, a little tightening of her jaw. "I will bring them down halfway," she said. "Whenwill he ride?"

"Two days," he said, trying to hasten the estimate; and thought again of the sores. "Maybe."

It was a dark thought went through Morgaine's eyes—was a thought the surface of which he knew how to read and the depth of which he did not want to know.

"It is not his planning," he said, finding himself the prisoner's defender.

"Aye," Morgaine said quietly, angrily and turned and walked uphill after the things he had asked.

She brought the things he asked back down to him, no happier. "Mind, we have no abundance of anything."

"We are far from the road," Vanye said. It was the only extenuation of their situation he could think of.

"Aye," she said again. There was still anger. It was not at him. She had nothing to say—was in one of her silences, and it galled him in the one sense and frightened him in the other, that they were in danger, that he knew her moods, and her angers, which he had hoped she had laid aside forever. But it was a fool who hoped that of Morgaine.

He took what she gave him and walked back to the bank, and there sat down, a little distance from their prisoner—sat down, trying to smother his own frustration which, Heaven knew, he dared not let fly, dared not provoke his liege to some rashness—some outright and damnably perverse foolishness, he told himself, of which she was capable. She scowled; she was angry; she didnothing foolish and needed no advice from him who ought well to know she was holding her temper very well indeed, Heaven save them from her moods and her unreasonable furies.

The focus of her anger knew nothing of it—was enclosed in his own misery, shivering and trying, between great tremors of cold and shock, to dry his hair.

"Give over," he said, and tried to help. Chei would none of it, shivering and recoiling from him.

"I am sorry," Vanye muttered. "If I had known this, Lord in Heaven, man—"

Chei shook his head, clenching his jaw against the spasms a moment, then lay still, huddled in the blanket.

"How long," Vanye asked, "how long had you been there?"

Chei's breath hissed between his teeth, a slow shuddering.

"Why," Vanye pursued quietly, "did they leave you there?"

"What are you? From where? Mante?"

"Not from hereabouts," he said. The sun shone warm in a moment when the wind fell. A bird sang, off across the little patch of meadow. It meant safety, like the horses grazing above them on the slope.

"Is it Mante?" Chei demanded of him, rolling onto his back and lifting his head, straining with the effort.

"No," Vanye said. "It is not." And reckoned that Mante was some enemy, for Chei seemed to take some comfort in that, for all that his jaw was still clamped tight. "Nor anywhere where they treat men as they treated you. I swear you that."

"She—" The man lay back and shifted desperate eyes toward their camp.

"—is not your enemy," Vanye said. "As I am not."

"Are you qhal?"

That question took the warmth from the daylight.

"No," Vanye said. "That I am not." In Andur-Kursh the fairness of his own brown hair was enough to raise questions of halfling blood. But the one who asked was palest blond; and that puzzled him. "Do I look to be?"

"One does not need to lookto be."

It was, then, what he had feared. He thought before he spoke. "I have seen the like. My cousin—was such a man."

"How does he fare?"

"Dead," Vanye said. "A long time ago." And frowned to warn the man away from that matter. He looked up at a motion in the edge of his vision and saw Morgaine coming down the hill toward them, carefully—a warlike figure, in her black and silver armor, the sword swinging at her side, either hand holding a cloth-wrapped cup she was trying not to spill.

Chei followed his stare, tilting his head back, watching her as she came, as she reached the place where they sat and offered the steaming cups.

"Thank you," Vanye said, as he took his cup from her hand, and took Chei's as well.

"Against the chill," Morgaine said. She was still frowning, but she did not show it to Chei, who lay beneath his blanket. "Do you need anything?" she asked, deliberately, doggedly gracious. "Hot water?"

"On the inside of him will serve," Vanye said. "For the rest—the sun is warm enough when the wind falls."

She walked off then, in leisurely fashion, up the hill, plucked a twig and stripped it like some village girl walking a country lane, the dragon sword swinging at her side.

She was, he reckoned, on the edge of a black rage.

He gave Chei his cup and sipped his own, wrinkling his nose as he discovered the taste. " 'Tis safe," he said, for Chei hesitated at the smell of his. "Tea and herbs." He tasted his again. "Febrifuge. Against the fever. She gives us both the same, lest you think it poison. A little cordial to sweeten it. The herb is sour and bitter."

"Qhalur witch," the man said, "into the bargain."

"Oh, aye," Vanye said, glancing at him with some mild surprise, for that belief might have come out of Andur-Kursh. He regarded such a human, homelike belief almost with wistfulness, wondering where he had lost it. "Some say. But you will not lose your soul for a cup of tea."

He had, he thought when he had said it, lost his for a similar matter, a bit of venison. But that was long ago, and he was damned most for the bargain, not what sustenance he had taken of a stranger in a winter storm.

Chei managed to lean over on his elbow and drink, between coughing, and spilled a good amount of it in the shaking of his hands. But sip after sip he drank, and Vanye drank his own cup, to prove it harmless.

Meanwhile too, having considered charity, and the costs of it on both sides, he delved one-handed into the saddlebags and set out a horn container, intricately carved.

And perhaps, he thought, a scrupulous Kurshin man would regard the contents of that little container as witchcraft too.

"What is that?" Chei asked warily, as he finished his cup.

"For the sores. It is the best thing I have. It will not let the wounds scab, and it takes the fire out."

Chei took the box and opened it, taking a little on his fingers and smelling of it. He tried it on the sore on the inside of his knee, his lip caught between his teeth in the patient habit of pain; but soon enough he drew several deep breaths and his face relaxed.

"It does not hurt," Vanye said.

Chei daubed away at himself, one wound and the other, the blanket mostly fallen about him, his drying hair uncombed and trailing water from its ends. Vanye took a bit on his own fingers and covered the patches that Chei could in no wise reach, those on his shoulders, then let Chei do the rest.

"Why?" Chei asked finally, in a phlegmy voice, after a cough. "Why did you save me?"

"Charity," Vanye said dourly.

"Am I free? I do not seem to be."

Vanye lifted a shoulder. "No. But what we have we will share with you. We are in a position—" He drew a breath, thinking what he should say, what loyalties he might cross, what ambush he might find, all on a word or two. "—we do not want to make any disturbance hereabouts. But then, perhaps you have no wish to be found hereabouts—"

The man said nothing for a moment. Then he reached inside the blankets to apply more of the salve. "I do not."

"Then we do have something to talk about, do we not?"

A pale blue stare flicked toward him, mad as a hawk's eye. "Have you some feud with Gault?"

"Who is Gault?"

Perhaps it was the right bent to take. Perhaps the man in his turn thought him mad—or a liar. Carefully Chei took a fresh film of salve on his fingers and applied it, and winced, a weary flinching, premature lines of sunburn and pain around the eyes. "Who is Gault?" he echoed flatly. "Who is Gault. Ask, whatis Gault?—How should you not know that?"

Vanye gave another shrug. "How should we? I know great lords aplenty. Not that one."

"This is his land."

"Is it? And are you his man?"

"No," Chei said shortly. "Nor would I be." He lowered his voice, spoke with a quickening of breath. "Nor, unlike you, would I serve the qhal."

It was challenge, if subdued and muttered. Vanye let it fly, it being so far off the mark. "She is my liege," he said in all mildness, "and she is halfling, by her own word. And in my own land folk called her a witch, which she is not. I should take offense, but I would have said the same, once."

Chei occupied himself in his injuries.

"It was this Gault left you to die," Vanye said. "You said that much. Why? What had you done to him?"

It was that hawk's stare an instant. There was outrage in it. "To Gault ep Mesyrun? He lives very well in Morund. He drains the country dry. He respects neither God nor devil, and he keeps a large guard of your kind as well as qhal."

"Tell me. Do you think he would thank us for freeing you?"

That told. There was a long silence, a slow and evident consideration of that idea.

"So you may reason we are not his friends," Vanye said, "and my lady has done you a kindness, which has so far gained us nothing but an alarm in the night and myself a few bruises. Had you rather fight us to no gain at all? Or will you ride with us a space—till we are off this lord Gault's land?"

Chei rested his head in his hands and remained so, sinking lower with his elbow against his knee.

"Or do you mislike that idea?" Vanye asked him.

"He will kill us," Chei said, and lifted his face to look at him sidelong, head still propped against his hand. "How did you find me?"

"By chance. We heard the wolves. We saw the birds."

"And by chance," Chei said harshly, "you were riding Gault's land."

The man wanted a key—best, it seemed, give him a very small one. "Not chance," Vanye said. "The road. And if our way runs through his land, so be it."

There was no answer.

"What did you do," Vanye asked again, "that deserved what this Gault did? Was it murder?"

"The murder was on their side. They murdered—"

"So?" Vanye asked when the man went suddenly silent.

Chei shook his head angrily. Then his look went to one of entreaty, brow furrowed beneath the drying and tangled hair as he looked up. "You have come here from the gate," Chei said, "if that is the way you have come. I am not a fool. Do not tell me that your lady is ignorant what land this is."

"Beyond the gate—" Vanye considered a second time. It was a man's life in the balance. And it was too easy to kill a man with a word. Or raise war and kill a thousand men or ten thousand. There was a second silence, this one his. Then: "I think you have come to questions my lady could answer for you."

"What do you want from me?" Chei asked.

"Simple things. Easy things. Some of which might suit you well."

Chei's look grew wary indeed. "Ask my lady." Vanye said.

It was a quieter, saner-seeming man Vanye led, wrapped in one of their two blankets, to the fireside where Morgaine waited, Chei with his hair and beard clean and having some order about it once he had wet and combed it again. He was barefoot, limping, wincing a little on the twigs that littered the dusty ground. He had left all his gear down on the riverside—Heaven knew how they would salvage it or what scouring could clean the leather: none could save the cloth.

Chei set himself down and Vanye sat down at the fireside nearer him than Morgaine—in mistrust.

But Morgaine poured them ordinary tea from a pan, using one of their smaller few bowls for a third cup, and passed it round the bed of coals that the fire had become, to Vanye and so to Chei. The wind made a soft whisper in the leaves that moved and dappled the ground with a shifting light, the fire had become a comfortable warmth which did not smoke, but relieved what chill there was in the shade, and the horses, the dapple gray and the white, grazed a little distance away, in their little patch of grass and sunlight. There was no haste, no urgency in Morgaine.

Not to the eye, Vanye thought. She had been quiet and easy even when he had come alone up the hill bringing the cups, and told her everything he could recall, and everything he had admitted to Chei—"He knows the gates," Vanye had said, quickly, atop it all. "He believes that is how we got here, but he insists we lie if we do not know this lord Gault and that we must know where we are."

Morgaine sipped her tea now, and did not hasten matters. "Vanye tells me you do not know where we come from," she said after a moment. "But you think we should know this place, and that we have somewhat to do with this lord of Morund. We do not. The road out there brought us. That is all. It branches beyond every gate. Do you not know that?"

Chei stared at her, not in defiance now, but in something like dismay.

"Like any road," said Morgaine in that same hush of moving leaves and wind, "it leads everywhere. That is the general way of roads. Name the farthest place in the world. That road beyond this woods leads to it, one way or the other. And this Gate leads through other gates. Which lead—to many places. Vanye says you know this. Then you should know that too. And knowing that—" Morgaine took up a peeled twig to stir her tea, and carefully lifted something out of it, to flick it away. "You should know that what a lord decrees is valid only so far as his hand reaches. No further. And I have never heard of your lord Gault, nor care that I have not heard. He seems to me to be no one worth my trouble."

"Then why am I?" Chei asked harshly, with no little desperation.

"You are not," Morgaine said. "You are a considerable inconvenience."

It was not what Chei had, perhaps, expected. And Morgaine took a slow sip of tea, set the cup down and poured more for herself, the while Chei said nothing at all.

"We cannot let you free," Morgaine said. "We do not care for this Gault; and having you fall straightway into his hands would be no kindness to you and no good thing for us either. Quiet is our preference. So you will go with us, and somewhere we shall have to find you a horse—by one thing and the other I suppose you are familiar with horses. Am I wrong?"

Chei stared at her, somewhere between incredulity and panic. "No," Chei said faintly. "No, lady. I know horses."

"And our business is not truly needful for you to know, is it? Only that it has become yours, as your safety has become conditional on ours—as I assure you it is. We will find you a horse—somewhere hereabouts, I trust. Meanwhile you will ride with Vanye—as soon as you are fit to ride. In the meanwhile you eat our food, sleep in our blankets, use our medicines, and repay us with insults." All of this so, so softly spoken. "This last will change. You have naught to do today but lie in the sun, in what modesty or lack of it will not affect me, I do assure you. You do not move me.—How wide are Gault's lands? How far shall we ride before we cease to worry about his attacking us?"

Chei sat there a moment with a worried look. Then he bit his lip, shifted forward and pulled a half-burned stick out of the coals to draw in the dirt with it. "Here you found me. Here the road. Back here—" He swept a wide, vague area with the stick. "The gate from which you came." The stick moved on to inscribe the line of the road running past the hill of the wolves, and up and up northward. "On either side here is woods. Beyond that—" He gestured out beyond the trees, where the river was, and where meadow shone gold. "The forest is scattered—a woods here, another there, at some distance from the road."

"You are well familiar with this lord's land," Morgaine said.

The stick wavered, a shiver that had no wind to cause it. "The north and the west I know. But this last I do not forget. I watched where they took us." The stick moved again, tracing the way, and slashed a line across the road. "This is the Sethoy, this river. It comes from the mountains. A bridge crosses it, an old bridge. The other side of it, northward across the plain, lord Gault's own woods begin; and his pastures; and his fields; and there is his hold, well back from the old Road. In the hills, a village. A road between. He has that too. There are roads besides the Old Road, there is a track goes across it from Morund and up again by the hills; there is another runs by Gyllin-brook—that runs along these hills and through them, up toward the village. None of these are safe for you."

"Further over on either side, " Morgaine said, and moved around the fire to indicate with her finger the left and the right of the road. "Are there other roads?"

"Beyond the western hills." Chei retreated somewhat from her presence, and used his stick to trace small lines.

"Habitations?"

"High in the hills. No friends of any strangers. They keep their borders against every outsider: now and again the lords from the north come down and kill a number of them—to prove whatever that proves. Who knows?"

There was perhaps a barb in that. Morgaine did not deign to notice it. She pointed to the other side. "And here to the east?"

"Qhalur holdings. Lord Herat and lord Sethys, with their armies."

"What would you counsel?"

Chei did not move for a moment. Then he pointed with the stick to the roads on the west. "There. Through the woods, beyond Gault's fields. Between Gault and the hillmen."

"But one reaches the trail by the old Road."

"There, lady, just short of Gault's woods. I can guide you—from there. I willguide you, if you want to avoid Gault's hold. I want the same."

"Where are youfrom?" Vanye asked, the thing he had not said, and moved close on the other side. "Where is your home?"

Chei drew in a breath and pointed close above Morund land. "There."

"Of what hold?" Morgaine asked.

"I was a free man," Chei said. "There are some of us—who come down from the hills."

"Well-armed free men," said Vanye.

Chei's eyes came at once back to him, alarmed.

"Are there many of your sort?" Morgaine asked.

Fear, then. True fear. "Fewer than there were," Chei said at last. "My lord is dead. Thatis my crime. That I was both armed, and a free Man. So once was Gault. But they took him. Now he is qhal—inside."

"Is that," Vanye asked, "the general fate of prisoners?"

"It happens," Chei said, looking anxiously from one to the other side of him.

"Tell us," Morgaine said, shifting position to point at the road where it continued. "What lies ahead?"

"Other qhal. Tejhos. Mante."

"What sort of place?" Vanye asked.

"I have no knowledge. A qhalur place. Youwould know, better than I."

"But Gault knows them."

"I am sure," Chei said in a hoarse small voice. "Perhaps you do."

"Perhaps we do not," Morgaine said softly, very softly. "Describe the way north. On the old Road."

Chei hesitated, then moved the stick and drew the line northward with a large westward jog halfway before an eastward trend. "Woods and hills," he said. "A thousand small trails. Above this—is qhalur land. The High Lord. Skarrin."

"Skarrin. Of Mante." Morgaine rested her chin on her hand, her brow knit, her fist clenched, and for a long moment were no more questions. Then: "And what place had Men in this land?"

Unhesitatingly, the stick indicated the west. "There." And the east, about Morund. "And there. Those in the west and those who live in qhalur lands. But in the west are the only free Men."

"Of which you were one."

"Of which I was one, lady." There was no flinching in that voice, which had become as quiet as Morgaine's own. "You are kinder than Gault, that is all I know. If a man has to swear to some qhal to live—better you than the lord that Skarrin sent us. I will get you through Gault's lands. And if I serve you well—believe me and trust my leading when you come near humans, and I will guide you through."

"Against your own," Vanye said.

"I was Gault's prisoner. Do you think human folk would trust me again? There have been too many spies. No one is alive who went through Gyllin-brook, except me. My lord Ichandren is dead. My brother is dead—Thank God's mercy for both." For a moment his voice did break, but he sat still, his hands on his knees. "No one is alive to vouch for me. I will not raise a hand against human folk. But I do not want to die for nothing. One of my comrades on that hill—he let the wolves have him. The second night. And I knew then I did not want to die."

Tears spilled, wet trails down his face. Chei looked at neither of them. His face was still impassive. There were only the tears.

"So," Morgaine said after a moment, "is it an oath you will give us?"

"I swear to you—" The eyes stayed fixed beyond her. "I swear to you—every word is true. I will guide you. I will guide you away from all harm. On my soul I will not lie to you, lady. Whatever you want of me."

Vanye drew in a breath and wrapped his arms about him, staring down at the man. Such terms he had sworn, himself, ilin-oath, by the scar on his palm and the white scarf about the helm—outcast warrior, taken up by a lord, an oath without recourse or exception. And hearing that oath, he felt something swell up in his throat—memory of that degree of desperation; and a certain remote jealousy, that of a sudden this man was speaking to Morgaine as his liege, when he knew nothing of her; or of him; or what he was undertaking.

God in Heaven,liyo, do you trust this man, and do you take him onmy terms– have I trespassed too far, come too close to you, that now you take in another stray dog?

"I will take your oath," Morgaine said. "I will put you in Vanye's charge."

"Do you believe him?" Morgaine asked him later, in the Kurshin tongue, while Chei lay naked in the sun on a blanket, sleeping, perhaps—far enough for decency on the grassy downslope of the riverside, but still visible from the campfire—sun is the best thing for such wounds, Morgaine had said. Sun and clean wind.

Not mentioning the salve and the oil and the matter of the man's fouled armor, which there was some salvaging, perhaps, with oil and work.