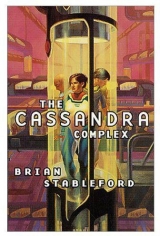

Текст книги "The Cassandra Complex"

Автор книги: Brian Stableford

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

THREE

Lisa paused in the doorway of Mouseworld, content for the moment to look inside without actually stepping over the threshold. There were too many people there already.

She placed her right hand against her sternum, not caring that the blood oozing from the dressing would stain the front of her tunic. The pain of the rip was definitely a feeling now as well as a fact, and the fumes were making her head ache. To make matters worse, the tiredness she’d been unable to cultivate while she lay awake in bed had now descended upon her like a pall. She had never felt less like throwing herself into her work.

The stink was the worst of it—but that was partly because the smoke spiraling from every direction in the hectic airflow made it difficult to see. The sheer faces of almost undifferentiated blackness might as well have been mere shadows. Oddly enough, there seemed to be hardly any warmth left in the cavernous space; the sharp autumn air circulating through the blown-out windows had carried away most of the heat, even though oily smoke still seeped from the molten remains of the plastic faces that were once cages housing small animals.

Lisa had to squint and concentrate hard to make out the vaguest outlines of the thousands of tiny corpses within the walls of shadow. Most of them must have been roasted rather than burned, but it was only in her imagination that the chorus of five hundred thousand agonized mice sounded obscenely loud. Mice weren’t equipped for screaming and within a couple of seconds, the intense heat and smoke must have robbed them of what voices they had.

The central H Block had suffered worst of all. It didn’t require an expert to guess that the incendiaries—of which there must have been at least two—had been placed in the coverts of the H-shaped area.

The main experiment, involving the four mouse “cities” arranged around the walls of the room, had run for decades. It had been famous in its way, but it had been regarded as a mere curiosity—a kind of scientific folly—even in 2002, when Lisa had arrived, shortly after her twenty-second birthday, impatient to be trained in all the hot new techniques of DNA analysis. She had already joined the police force, and had gone through basic training of a sort during the summer months.

If the Mouseworld cities had been a folly then, what were they now in 2041? The passage of time had lent them a certain dignity, although all the claims made over the years for their renewed relevance rang slightly hollow to those in the know. The human population explosion had indeed produced all the dire effects that prophets such as Morgan Miller had predicted, but careful analysis of the physiological tricks that the mice of Mouseworld had mastered had made not a jot of difference. Those humans who followed the mouse example had needed no help to do so, and those who were Calhounian rats through and through could not have been changed by any plausible intervention.

Half a dozen firemen were wandering around aimlessly, two of them still in full breathing apparatus and two others carrying huge axes in a fashion suggesting they were longing to get on with the job of clearing the debris off the staircases and catwalks—a job that would have to wait until the Fire Investigation Team had made a meticulous inspection of the site, probably in company with experts from the Bomb Squad. The axemen had taken their masks off, although the SOCO workers operating under the supervision of Steve Forrester were fully suited.

Lisa still outranked Forrester, in theory at least, but she wasn’t his line manager; he was the up-and-coming heir-apparent to the entire department. He came over as soon as he noticed her, but it was a token gesture.

“Nothing much for us here,” he said. “I sent Max and Lydia with Burdillon in the ambulance—we might get something from his clothing, if we’re verylucky. As he came through the door, he was shot and fell sideways to his right. One of the bombers got a hold of his jacket and dragged him thirty meters down the corridor. His jacket was dead and the bomber was wearing smart gloves, but there’s still a possibility that something stuck.”

When Lisa nodded an acknowledgment, Forrester immediately turned away. Although the senior fireman must have deduced by now that she was police, he wasn’t in any hurry to talk to her. She was, after all, a middle-aged woman, even if her passcard did state that she was a doctor of philosophy as well as an inspector. She seemed to have held the rank of inspector forever; three reorganizations of the relationship between forensic-science officers and the main body of the force hadn’t succeeded in solving the problem of a grotesquely inappropriate and largely tokenistic ranking system.

When the senior fireman finally condescended to approach her, Lisa stepped over the threshold and moved to the left of the door so they wouldn’t be in the way.

“Your mice, were they?” asked the officer as he squinted at the fine print on her card, having rubbed his eyes to clear away the last few smoke-induced tears. His hair was dyed black. The fire service, like the police force, was an institution in which youth and physical fitness were traditionally held in great esteem; they seemed destined to be the nation’s last bastions against the quiet revolution of gray power. Lisa wondered whether the fireman viewed the prospect of premature redundancy with the same vaguely nauseating apprehension that had become her own mind’s rest state.

“Not ours,” she told him. “We still subcontract some animal work to the university, but the vast majority of the mice in here weren’t on active service anymore. Those that weren’t in the cities—the ones in the central block, that is—were mostly obsolete models and other GM strains preserved as library specimens. All current work is conducted on the upper floors.”

The fireman nodded sagely, although he probably didn’t have a clue as to what she meant by “obsolete models” and certainly didn’t care. “Good doors, fewer windows up there,” he said approvingly. “Certain amount of damage outside but not much in. Parallel labs on this floor came off worse, even though heat always tries to go straight up. There was a lotof heat, but it didn’t last long. They used a fierce accelerant, but most of the local material was decently retardant. Whole thing was a matter of Bang! Whoosh! Bob’s your uncle.”

Lisa thought about that for a moment or two. “Did the bombers expect it to spread upstairs?” she asked. “Were they hoping to destroy the whole wing?”

“Don’t know what they expected or hoped,” the black-haired man replied punctiliously. “Not my job to speculate.”

“I’m just trying to understand why they put the bomb in here,” Lisa said, struggling to remain patient in spite of her stinging hand and aching head. “Might Mouseworld have been the most convenient point they could reach in order to launch an attack on the high-security facility above it?”

“Maybe,” said the fireman dubiously. “They certainly had easy access here—door was unlocked, not broken open. Then again … has to be off the record, because I’m not the man supposed to swear to it in court, but Ireckon there were four devices, placed low down to blast in all four directions. Never saw anything like thisbefore”—he waved an arm at the blackened walls, presumably referring to the vast arrays of interconnected cages—“but if I had to guess, I’d say the bombs were placed to make sure they got all the animals, and nobody gave a damn about the rest of the wing or anything upstairs. Why would anyone do that, hey?”

The fireman was trying hard not to sound anxious, but there had to be at least as many rumors running around Widcombe Fire & Rescue Station as there were around East Central Police Station. Loyal public servants weren’t allowed to say there was a war on, but they all knew full well that millions of people were dying of hyperflu in Mexico, North Africa, and Southeast Asia, and not because their chickens’ resident viruses had been possessed by some kind of mutational madness. “It’s a mystery to me,” Lisa admitted tactfully. “Who would want to assassinate five hundred thousand redundant mice? If there are any significant experiments running at the moment—and I doubt there’s anything much concerned with infective viruses—those animals are upstairs, locked in steel safes surrounded by moats of bleach. There was nothing dangerous here; the lab assistants only wore masks and gloves because of the regs. All the mice on the outer walls were part of a famous experiment that had been running since before you and I were born.”

“Doesn’t do to be famous nowadays,” the fireman observed. “Even if you’re only an experiment. Hear about that TV weathergirl got whacked last week? Don’t care what they say about the impending frustrations of containment—world can’t get much crazier than it already is.”

’Do you have any idea of what kind of devices were used?” Lisa asked, knowing she ought to ask the questions Mike Grundy would want answered, even if the investigation would be taken out of his hands before noon. “Have you seen anything like them before?”

“Better ask the experts,” the black-haired man told her cautiously. “Most of the arson I see is kids with cans of gasoline or beer-bottle Molotovs.”

“You mean that this was a professional job?”

“No such thing,” he said contemptuously. “Nobody makes a living torching things. Anyway, every common or garden lunatic can decant cordon-bleu bomb-making instructions from the net. Kids only use gas cans because they’re lazy and because gas gets the job done—if they wanted to do it the fancy way, they could easily find out how.”

“Why was thisjob done the fancy way?” Lisa persisted. “What was accomplished here that couldn’t have been done with a can of gasoline and a match?”

“One-hundred-percent mortality,” he said succinctly. “Like I said, all the local materials, apart from flesh, are decently fire-retardant, so the structure held up far better than the inhabitants. As you’d expect. Nothing’s fireproof, of course, but labs in tall buildings have to observe the regulations. Mind you, fancy accelerants aren’t easy to buy or cook up in the kitchen, so it’s unlikely to have been actual kids.Some organization, I’d say. Some intelligence too. If I were you, I’d assume—at least to start with—that what they wanted to do was what they actually did. They certainly made sure they didn’t leave a single living thing alive.”

Lisa looked up at the blackened wreckage looming eighteen or twenty feet above her on three sides. She remembered the labels that had been proudly pasted atop each vertical maze: LONDON; PARIS; NEW YORK; ROME. There was no trace of them now—they, at least, had not been made of fire-retardant plastic. The mouse cities weren’t Edgar Burdillon’s experiment and never had been—he had always regarded them as something of a space-wasting nuisance, so there was a certain sour irony in the fact that he had gone to their defense and been hurt in consequence. It was difficult to specify exactly whose experiment the cities were now that their original founders were long retired. They were simply theexperiment—a hallowed tradition, not merely of the Applied Genetics Department, but the university’s entire bioscience empire. So why, Lisa wondered, should she feel such an acute sense of personal loss as she stared dumbfounded at the ruins? Was it because the stability of the mouse cities had somehow come to symbolize the stability of her own personality—essentially undisturbed save for a couple of “chaotic fluctuations” way back in the zero decade?

Lisa couldn’t believe that any terrorist organization could possibly have a grudge against the mouse cities. Their size made them the most conspicuous victims of the attack, but their destruction could have been the unfortunate byproduct of a determination to destroy some or all of the other mice kept in the lab complex: the library specimens in the central section. If so, which ones were the bombers most likely to have been after– and why?

The GM strains in the H Block had been the detritus of hundreds, maybe thousands, of mostly discontinued experiments. Lisa doubted that anyone currently active in the department was acquainted with the nature and history of more than a few dozen of them. There would be a supposedly complete catalogue on the computer, of course, but every data bank had to be kept up to date, and everybody knew that records of that kind never matched reality with any exactitude, because errors accumulated over the years and no one could ever be bothered to sort them out—especially if nobody cared passionately about the accuracy of the data. The animals in the tightly sealed biohazard units on the upper floors would be comprehensively documented, but not these. It was possible that nobody would ever know for sure exactly what had been lost.

The fireman had turned away while Lisa was thinking, and she couldn’t see any need to call him back. Someone was coming up the corridor behind her and she put her head around the door to see who it was, after briefly rubbing her smoke-irritated eyes.

Lisa recognized the campus security guard responsible for the building. He’d been around almost as long as she had. His name was Thomas Sweet, although Lisa realized with a slight shock that she’d never actually had occasion to address him by name. He knew her only as an occasional visitor, but she obviously seemed to him to be a sympathetic figure—a possible ally against all the uniformed men and “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” The deeply mournful look brought forth a faint but heartrending echo in her own being.

“Miss Friemann?” he said desolately. “Is that you?”

“Yes,” she said, unworried by the fact that he hadn’t called her “Doctor,” let alone “Inspector,” although she certainly wasn’t unaware of it. “What happened, Mr. Sweet? Have you collected the wafers from the security cams?”

“Gave them to a DS,” Sweet assured her. “DI Grundy wants to run through them again, but I’ve taken a peek and the bombers are all wrapped up. Won’t have left much evidence for you, thanks to the so-called smart fabrics they were wearing.” His own uniform was thoroughly dead, and Lisa guessed that his private wardrobe was even farther behind the times than her own.

“We’ll get something,” she said, trying to sound optimistic.

“Wasn’t my fault, Miss,” Sweet insisted. “They hacked into the system and sent false pictures to my VDU’s. They had smartcards, you know—didn’t trigger a single alarm.”

“How many were there?” she asked, unable to remember whether she’d already been told.

“Three of them. Heads inside helmets—purpose-built, not ordinary motorcycling helmets. Looked like they were pretending to be SAS commandos. Only one thing I could make out for sure.”

“What was that?”

“They were women. Two of them, at least. Third might have been a man—probably was, judging by the way he dragged the prof along the corridor like a sack of potatoes, but not the ones with dart guns. Doesn’t make much difference these days. Remember that evil bitch you banged up after the Dog Riots thirty years back? What was it she called herself?”

“Keeper Pan,” Lisa said automatically, slightly surprised by the readiness of her memory.

“Let her out again soon enough, though, didn’t they? Animal Liberation Front!Is thiswhat they call liberation?”

For the moment, Lisa thought, Animal Liberationists were probably the least likely suspects. Even in their heyday, animal libbers had used firebombs only against people. Mice were right at the bottom of their hierarchy of deserving species, way below pigs and rabbits, but they were innocents nevertheless. Keeper Pan and her friends would never have firebombed Mouseworld. Lisa did, however, pause to wonder whether the person who’d shot the phone out of her hand could possibly have been a woman. It had been too dark to judge the shape of the black shell-suit, but there might have been something else that would give her a clue, if only she could focus her memories….

“He had a lot of stuff in here, didn’t he?” the security man went on. “Stuff from way back—been inoculating mice with voodoo for forty years, they say, trying to work magic. Never came to anything much, though, did it?”

After a moment’s confusion, Lisa realized that the hein Sweet’s statement wasn’t Edgar Burdillon, but Morgan Miller.

“Did they try to get into any of the other labs or offices?” she asked sharply.

Sweet shook his head. “Came straight here,” he said. “Seemed to know exactly what they were doing. Didn’t go to the upper floors at all. Why would they want to burn Mouseworld, Miss Friemann?”

“I don’t know,” Lisa said, marveling at the absurdity that the casual shooting of a once-eminent scientist did not seem bizarre at all by comparison with the destruction of a classic experiment in animal population dynamics. The fact that Ed Burdillon had been driven away in an ambulance, his life endangered by toxic fumes, hardly seemed to have registered with the old man.

“I tried to call him,” said Sweet—still presumably referring to Morgan Miller. “So did the police. He isn’t answering his phone.”

“Is he away?” Lisa asked.

“Not that I know of,” the security guard replied, still shaking his head in disbelief. “I tried Stella too, but everyone sets their answer-phones these days, day and night alike. Too many nuisance calls, I guess.”

Lisa knew that Stella Filisetti was Morgan Miller’s latest research assistant. She didn’t know if Morgan was screwing her, but she assumed that Sweet believed he was. It had been Morgan’s habit since time immemorial, and he wasn’t the kind of man to give up on his habits while there was still breath in his body.

Morgan had been seventy-three years old on his last birthday, but the last time Lisa had seen him, he’d assured her that he was “as fit as a flea.” Seventy-three wasn’t old these days, no matter what Police Admin and the top men at Fire & Rescue might think. The university certainly hadn’t tried to force Morgan to retire, even though the younger members of the department were sometimes wont to say, with a sneer, that he hadn’t produced a single worthwhile result in thirty years.

“I’m sorry, Miss,” Thomas Sweet went on. “Maybe I should’ve called you too, but I didn’t have your number. I dialed 999 to get the fire department and the police, then I tried Professor Burdillon’s office. Couldn’t get through, of course—I didn’t know then that he’d gone downstairs. I tried Dr. Miller and got no reply, so I tried Stella, then Dr. Chan. No reply from any of them. Not one.’9He seemed deeply resentful of his failure, as if he suspected that he would be held responsible for it.

Their conversation was interrupted by another new arrival: a woman in her mid-thirties, with short-cropped hair and a raptorial attitude. Lisa had been hoping to see Mike Grundy before Judith Kenna found her, but it was too late now.

It didn’t seem to have occurred to the chief inspector that there were times when a professional smile, however sardonic, wasn’t entirely appropriate. “Mr. Sweet,” she said mildly, “DS Hapgood would like another word with you.”

She waited for the security guard to go through the doorway before continuing. “It’s good of you to race out here to give us the benefit of your special expertise, Dr. Friemann, but you really should have remained at the other crime scene. Senior officers ought to set an example in procedural matters, don’t you think? I see that you’re hurt too. Is that a bandageon your hand? You really ought to have seen a doctor before rushing off like that—Detective Inspector Grundy seems to have been extremely irresponsible.”

“Don’t blame Mike,” Lisa said frostily. “My home first-aid kit’s ancient, but the dressing will do the job just as well as a fancy sealant. It’s just a slight cut in an awkward place, plus a few scratches on my arm. There was nothing I could do at home but trample on evidence—and I dohave special knowledge of this location and the victim. When the men from the Ministry of Defence get here, they’ll want to talk to me.”

“I’m sure they will,” the chief inspector purred. “Have you formed any conclusions?”

“Not yet,” Lisa admitted, wishing there were some vital clue in plain view whose significance she alone had been able to see. Desperate to even the score, she said: “Have you managed to figure out why they blacked out the center of town?”

“I think so,” said Kenna, her smile becoming smug as well as sardonic. “I presume they did it partly to provide getaway cover for the vehicles carrying the bombers and your own intruders, but the main reason must have been to cloak the third—and probably most important—part of their scheme.”

Lisa suppressed a curse and managed to sound completely neutral as she said: “Which was?”

“The abduction of Dr. Morgan Miller,” the chief inspector informed her.