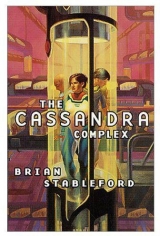

Текст книги "The Cassandra Complex"

Автор книги: Brian Stableford

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“The long and the short of it is that the process of mosaic reconstruction stopped the aging process in its tracks. The transgenic mice were rejuvenating themselves. Initially, of course, that did my specimens more harm than good because the newborns, which remained newborns by virtue of their new power of self-renewal, couldn’t survive the interruption of their developmental processes. They died of superabundant youth. Once I’d figured out what was going on, though, I soon found out that the retrovirus could also be used to infect adults. Although the effects were variable, some of the inoculated adults were stabilized by the transformation. Their life spans were dramatically extended—and I’m not talking thirty or forty percent. In time, I found that a substantial minority were living ten or twenty times as long as their parents. A few lived a hundred times as long—and the current record holders were still extending the multiplier two days ago. Were the angels of wrath telling the truth when they said they’d torched Mouseworld?”

“Yes, they were,” Lisa confirmed.

Morgan Miller sighed again, but this time there was an element of theatre in the sigh. “It was a long time, of course, before I was convinced that even a few of the mice were authentically emortal, but the cream of the crop has stayed stable, fit, and healthy for forty years. A few were sterile, but not all. The real champions didn’t cannibalize all the fused oocytes; every now and again they gave birth to litters of daughters. Most of the offspring failed to develop, like the newborns I’d transformed myself, but a few grew to maturity before stabilizing. The selective regime progressed by degrees to the inevitable terminus: a population of emortal female mice whose daughters were likewise emortal. It took time, but when the potential’s there and the regime is stern, natural selection is no slouch.

“Long before I was convinced they were authentically emortal, I’d begun introducing the mice to the cities, for exactly the same reason that Chan wanted to introduce his augmented specimens: to see how they’d fare in a stressful and competitive situation. Mine did a little better than his—obviously, or Stella would never have found the transformed mice—but not thatmuch better, and not for a long time. When you came along in 2002,1 only had half a dozen potentially emortal mice, and nineteen of the twenty offspring they had so far produced had died paradoxical deaths of superabundant youth. By the time I moved on to experiment with other species in ’09 or thereabouts, I had a hundred adult mice and the survival rate among the new litters was up to one in three. Even then, you see, I couldn’t be surethey’d live significantly longer than normal. If I had been, I might have told you … maybe.

“It was all so gradual, so uncertain, so surprising. You should be able to imagine how tentative my conclusions were when I first knew you, how much more needed to be done before I could be confident. Stella came in on the hind end of things, when everything was set and fixed, and she never tried to imagine how it must have been in the long and confusing beginning. All she saw, when she tumbled to what was going on in London and Rome, was a secret that I had kept for forty years. And all she cared about was the obvious—she and her friends didn’t pause long enough to wonder whether there was more.”

“They discovered that you’d found a technology of longevity,” Lisa said. “A technology that might be just as applicable to humans as to mice if the retrovirus could be tweaked. A technology that you had discovered at the turn of the century, and didn’t tell anyone else about until 2041, at which point you approached Dr. Goldfarb and Herr Geyer: both male, and both representative of secretive institutions with hidden agendas. I can understand why Helen Grundy, Arachne West, and other assorted backlash theorists thought that all their worst nightmares had come true. I can even understand why they started using the blowtorch when you tried to persuade them there was a catch that made it all worthless. There isa catch, isn’t there?”

“Oh, yes,” he said. “The catch to end all catches. I thought I might be able to work around it somehow, but I couldn’t. Maybe no one can.”

“An army would have stood a better chance than a lone hero,” Lisa pointed out. “That’s what science is supposed to be all about, isn’t it? Many hands make enlightenment work.”

“An army might have,” Morgan agreed. “What worried me was that an army might have liked the problem better than the solution. What’s good for mice isn’t necessarily good for humans—or dogs, come to that. We found out soon enough, way back at the turn of the century, that mouse models of human diseases had their limitations, because mice can tolerate some conditions that humans can’t. Mice may seem primitive and stupid to us, but there are some things they can tolerate that cleverer and more sophisticated mammals can’t.”

“Like emortality?”

“Like rejuvenation. People our age think of rejuvenation in terms of getting back to twenty-one and staying there forever. But what if the stopping point isn’t twenty-one? What if the stopping point is one? My survivor mice got past the point at which they were producing offspring that stabilized at a physicalage estimable in days, but body and mind each have their own aging processes. Mice are creatures of instinct, Lisa—they’re born with ninety percent of what they need to know hardwired into their brains. The little they need to learn can be learned over and over again without too much inconvenience. Even a rat needs to be cleverer than that, and a dog needs to be muchcleverer. You might not be able to teach an old dog new tricks, but a young dog has to be able to learn a lot and hold on to it all. The problem with the kind of rejuvenation my mice go in for is that it rejuvenates the brain as well as all the other parts of the body. It wipes out learning almost as fast as the learning goes in.

“What my retrovirus produces, even at the farthest end of the selection process, is emortal mice that are physically mature but mentally infantile. By introducing them into the Mouseworld cities, I eventually managed to prove that mice can live like that, even among their own mortal kind, because they can keep on learning the things they need to learn over and over again. The catch is that they’re probably the most advanced creatures that can.”

“The dogs,” Lisa said remembering. “The dogs on that stupid video the ALF circulated. Their voice-over claimed that the first lot they showed had been primed to produce an autoimmune reaction modeling mad cow disease, but they hadn’t. I knew they hadn’t—but I never thought to find out what hadbeen done to them. They were yours, weren’t they? Another project you hadn’t referred to the Ethics Committee—another breach of the law. You’d rejuvenated them—and the rejuvenation had wiped their minds clean of anything faintly resembling a personality.”

“If whoever filmed them hadn’t been in such a rush to get the product out, they’d have seen far worse,” Morgan admitted. “Are you still interested in taking the treatment, Lisa?”

“Emortality and murder all wrapped up in one little retrovirus,” she said. “The body lives forever but the human being becomes … not quite a vegetable, but not much more than a mouse. A zombie. Worse than a zombie.”

“That’s about the size of it,” he confirmed. “Not that I’ve tried any human experiments, of course. If I’ve missed my chance to have my little discovery enshrined in the textbooks as the Miller Effect, I’ll just have to take my place in the ranks of the historically anonymous. You can understand now why it didn’t seem like a good idea to share it, can’t you? Your friends couldn’t, and that’s part of the reason they wouldn’t believe me, but youcan.”

“We live in a plague culture,” Lisa said, more for Arachne West’s benefit than Morgan Miller’s. “Any tuppenny-ha’penny Cassandra with half a brain has been able to see for fifty years and more that World War Three would be fought with biological weapons. These days, even hobbyist terrorists use biological weapons if they can get them, in spite of all the problems they pose, because they’re so very modern, so very twenty-first century.And you’ve devised a biological weapon that works only on women—a biological weapon that has no rebound problem, provided that it’s deployed by uncaring males.”

“A nonlethal weapon that would turn most premenopausal women into zombies,” Miller added. “Zombies with the minds of mice.”

“Oh, shit,” Lisa murmured as the corollaries continued to unravel in her imagination. “And Arachne Westrefused to believe that? The perfect Real Woman wasn’t cynical enough to think that such a thing could exist? Or that there wouldn’t be people queuing up to use it if they knew it existed? Or armies avid to research the possibility, as soon as they knew it couldbe done?”

The irony in Morgan Miller’s smile was ghastly. “It’s far more probable,” he said, his voice sinking back to a whisper, “that what they couldn’t bring themselves to believe was that if that was really what I had, I’d kept quiet about it. They thought I was just trying to put them off.”

TWENTY-TWO

When Lisa eventually left the room, Morgan Miller stayed on the bed, content to wait. It wasn’t like him to be content to wait, but he didn’t seem to have the strength left to do anything else. He hadn’t been imprisoned very long, and the injuries inflicted by the blowtorch weren’t life threatening in themselves, but he was an old man. The shock to his system had been profound.

When Lisa came through the door, Arachne West commanded her to shut it behind her. She obeyed, but not because of the pistol the Real Woman was passing carelessly from hand to hand.

“You didn’t ask him the big question,” the bald woman observed.

Lisa was mildly surprised, having been more than impressed by the magnitude of the revelations she had obtained. For a moment or two, she thought that Arachne might have “Is it infectious?” in mind, not having been able to follow the details of Morgan’s concluding technical discourse about species-specific variant designs and attachment-mechanism disarmament, but then she realized that she was being stupid.

The big question in Arachne West’s mind was still: “Where’s the backup?”

The members of Stella Filisetti’s hastily contrived conspiracy still hadn’t found a record of the experiments or a map of the primal retrovirus. They had the mice, and the researchers who eventually obtained custody of the mice would be able to work back painstakingly from there, but Morgan Miller still had at least one neatly wrapped package of vital information stashed away, hidden somewhere among the disks, wafers, and sequins they hadn’t been able to remove from his house because their sheer quantity had made it impractical.

“He’ll tell me if I ask,” Lisa assured the Real Woman, “but we need to work out a deal first.”

“Sure,” Arachne said, too willingly to be entirely plausible. “Whatever he wants. As you’re so fond of pointing out, I’ve nothing left to bargain with.” But she was still passing the pistol from hand to hand.

“It istrue,” Lisa said. “What he told me just now. I’m sure of it.”

“It’s only a couple of hours since you were equally sure he couldn’t possibly have kept a secret from you for the last thirty-nine years,” the Real Woman pointed out. “But that’s a cheap shot. I know it’s true. I was prepared to believe it as soon as he came out with it. It was so horribly plausible—and I mean horriblyplausible.”

“So why did you start burning him?”

Arachne shrugged. “You know how it is with committee decisions,” she said. “There’s always some stupid fucker who won’t fall in with the party line. Collective responsibility always gives birth to collective irresponsibility. It wasn’t vindictiveness, Lisa—not on my part, anyhow. If I’d been running the show … but you know how the spirit of sisterhood works. Discussion good, hierarchy bad. Result: confusion decaying into chaos. I knew we’d lost the plot the moment he opened his mouth. You know what? I actually think he was right. I think he did the right thing, at least up to a point. There really are some things that man was not meant to know. Never thought I’d say that. Could I get anyone else to see it the same way, though? Could I fuck. Crazy times, hey?”

“I don’t,” Lisa murmured.

“Don’t what?”

“I don’t think he did the right thing. Not even up to a point. He should have let other people in. Not necessarily me, but somebody. Ed Burdillon or Chan. It’s not just collective responsibility that mothers irresponsibility if you don’t take precautions.”

Arachne West shook her head slightly, but there wasn’t the least hint of a smile about her forceful features. “‘Oh, what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive,’” she quoted. “Always been one of my favorites. So why’d you do it, Lisa? Have your ova stripped and frozen, I mean. That looked verysuspicious. Could even have got you killed if Stella and the other loose cannons had blasted off a few broadsides.” She obviously didn’t know how close she was to the truth.

Lisa sat down on the edge of the desk. “It was one of the things I used to debate with Morgan, back in the days when we were as close as close could be. Although he admitted that one of the major causes of the population explosion was the clause in the UN’s Charter of Human Rights that guaranteed everyone the right to found a family, he wasn’t opposed to it, and he didn’t altogether approve of the Chinese approach limiting family size by legislation. What was really needed, he always argued, was for people to accept the responsibility that went with the right: to exercise the right in a conscientious fashion, according to circumstance.

“There had been times in the past, he said, and might be times in the future, when the conscientious thing to do was to have as many children as possible as quickly as possible—but in the very different circumstances pertaining in the early years of the twenty-first century, the conscientious thing to do was to postpone having children for as long as possible. To refuse to exercise the right to found a family was, in his opinion, a bad move, because human rights are too precious to be surrendered so meekly. His solution to the problem had been to make a deposit in a sperm bank, with the proviso that it shouldn’t be used until after he was dead.

“I decided, in the end, to do likewise—but there was a slight technical hitch. Donor sperm was easy to acquire and by no means in short supply, but the procedure to remove eggs from a woman’s ovaries is much more invasive. Eggs were in such short supply that there was no provision in the contract for the kind of delay clause Morgan inserted. A donation was supposed to be a donation, and that was that—but the bank was prepared to make an informal compromise and agree to leave my eggs on long-term deposit unless the need became urgent. I figured that the principle remained the same, so I settled for that. It had nothing to do with Morgan’s emortality research.”

“Are you sure?” the Real Woman asked.

Lisa saw immediately what Arachne was getting at. Morgan had persuaded her to make the deposit. The arguments he had used were good ones, but in view of what she now knew, they probably had not been the ones foremost in his mind. Back in the first decade of the new millennium, he must have hoped that all the problems he’d so far encountered with his new technology were soluble. He must have hoped that he might one day be able to make human women emortal—always provided that they had enough eggs left in their ovaries—or eggs available that could be replaced therein.

No wonder it looked so suspicious, she thought. No wonder Stella Filisetti took it as proof that I knew.

“Tangled webs,” Arachne observed. “Wish I could spin ’em like that.”

“You don’t seem to be in any great hurry to get the answer to your big question,” Lisa observed.

“No,” the Real Woman admitted. “As a matter of fact, what I was instructed to do—or would have been if we were allowed to use words like ‘instructed’—was simply to keep you here as long as possible. There’s no way for me to avoid implication in the kidnapping, or for Helen, but the rest of the girls have scattered to the four points of the compass and they have to figure that they have a chance to get away. How many mice do you suppose Stella managed to get out before the bombers went in? Anybody’s guess, isn’t it? Your colleagues will intercept a few, but they won’t get them all. The committee figured that was the fallback position that we had to protect at all costs. As far as they’re concerned, my only utility now is to hold back the hounds as long as possible—which means, the way they see it, preventing you from unleashing the pack prematurely. I’m supposed to shoot you, if necessary.”

“And Morgan?”

“Him too. Some of them even think I might do it. I have this tough image, you see. Some people bluster and threaten but never shoot, and some don’t but do. Then there are the Stellas, who shouldn’t ever be trusted with fireworks at all. We started out with the intention of not killing anyone, and I’d rather finish the same way if I can, but you shouldn’t take too much for granted. I have no idea of what I might be capable of if the situation becomes desperate. God, listen to me. Ifthe situation becomes desperate! By nightfall, the men at the Ministry of Defence will know that there’s a really neat weapon whose specifications are hidden somewhere in Morgan Miller’s house. And unlike us, they have all the time in the world to search for it. How many other menwill get to hear about it, do you suppose?”

“Your people will get at least some of the mice,” Lisa pointed out. “Stella and Helen have seen to that. Once they have the mice, it’s only a matter of time before they get the retrovirus. It’s just a virus. A vaccine can be developed, given time—but it would save time if your people had the gene map.”

“It’s alla matter of time now,” Arachne agreed, “and there’s never been enough of it. I don’t much feel like following orders, given that I’m the one who’s left holding the baby. I’d prefer to get a hold of the data, if I can—on any terms you care to offer, although I don’t have much to offer now I’ve already told you that I’m not going to kill anybody. I’d also like a chance to run. I probably won’t get far, but sisterhood has its advantages. So—if you ask Miller the big question, will he give you the big answer? And if he does, what will youdo with it?”

“We might not have time to do anything with it,” Lisa pointed out. “By now, Smith’s people will probably have purged the phone records. They’ll be after Helen and everyone they suspect of involvement. They were already looking for you.”

“That’ll tie up a lot of manpower,” Arachne observed. “Everybody running this way and that, far too busy to stop and count the daisies. I suppose Miller’s house is under guard?”

Lisa nodded slowly. “Twice over, probably,” she said. “The MOD will have people there, as will the police.”

“I’d never get in, would I?” the Real Woman asked. “Even if I knew what I was looking for, I’d have no chance. A police officer who’s been seconded to the MOD team would be a different matter. You may be AWOL, but you’re still on the case.”

“And you’re still trying to recruit me,” Lisa said, although she knew she was merely stating the obvious. “Even after all these years.”

“And you’re still playing coy. Why would I have let Helen invite you here if I didn’t think you could be turned? And why would you have volunteered to come if you weren’t finally ripe for turning?”

“I just wanted to know what the hell was going on,” Lisa told her. “I didn’t realize you’d already figured it out. If I had—”

“You’d have come anyway. And now you do know what’s going on. Even Miller knew the time had come to hand his vile secret on to somebody—but I happen to think that his list of candidates stinks, and the Ministry of Defence is potentially even worse. You and I might find some better guardians, don’t you think?”

Another piece of the puzzle slotted into place in Lisa’s mind. In Morgan’s mind, the most significant thing that Ahasuerus and the Algenists had in common hadn’t, after all, been the fact that they each had an interest in longevity technology. It was that both organizations had a fundamental commitment to pacifism. Morgan had been trying to find someone to carry on his work who wouldn’t be interested in the weaponry potential of the imperfect retrovirus. No wonder he had been coy about telling Goldfarb and Geyer exactly what he had while he was probing the seriousness of their mission statements.

Why didn’t he come to me instead?she wondered. But she knew the answer to that. It wasn’t because she was a police officer—although that must have played a part—it was because she was sixty-one years old. At best, she’d have been a caretaker, and he was looking for a long-term arrangement. But now, like Arachne West, she was on the spot and on her own. If she asked him, Morgan would probably tell her where the information was, and if she moved quickly enough, she might be able to get it out of Morgan’s house before Peter Grimmett Smith found out what was at stake and let loose a whole army of assiduous searchers. She wouldn’t be stealing anything except time—but in a situation where time was of the essence, any margin of opportunity was a valuable commodity. Even if Arachne West was mistaken in her harsh judgment of Goldfarb and Geyer, there were undoubtedly other potential recipients of the new wisdom who would be far more interested in neutralizing its weaponry potential than exploiting it.

Lisa reminded herself that she was sixty-one years old and that her career was already in ruins. If Arachne West was willing to let her act, she was still in a position to do so, and even if the big woman-hunt were already underway, she probably still had time to play her own hand.

“Are you in?” Arachne West asked her.

“Of course I’m in,” Lisa said. “As you so rightly pointed out, why else would I be here?”