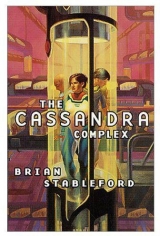

Текст книги "The Cassandra Complex"

Автор книги: Brian Stableford

Жанр:

Космическая фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

TWENTY

Lisa had no watch to tell her the time, but it was obviously too late now to do the run into what had once been the Bath city center in ten minutes. The morning rush hour was already well underway. The onboard computer, roused from quietude by the parking offense she’d committed on North Road, logged six more manifest offenses and four instances of contributory negligence. Its muted voice was still beeping plaintively about parking regulations when she abandoned it, but she figured she made it to the Recreation Ground Mall within a couple of minutes of the deadline she’d been given.

Lisa didn’t expect that her tardiness would make any difference; Helen’s imposition of a time limit was a meaningless gesture, born of the desire to pretend that she still had some degree of control over the situation. Lisa left Mike Grundy’s mobile in the car, having switched it off after the call to Helen.

She was not surprised to discover that Salomey was a clothing shop, specializing in ultrasmart costumes for ultrasmart women. A notice on the automatic door informed customers that THIS IS A WOMEN-ONLY SHOP, but that wasn’t unusual nowadays. The special intimacy of smart fabrics had given birth to a new modesty, and had brought a backlash in favor of privacy that had drawn many new kinds of social boundaries.

The Real Woman who watched Lisa from the purchase desk as she crossed the smart-carpeted floor to the dressing room looked completely out of place. Even if she hadn’t been so powerfully built, she would have stood out simply because she didn’t look as diffident as the younger sales assistants obviously fighting boredom while they waited for opening time. A clock on the wall told Lisa that the time was now eight thirty-five.

The woman waiting in the dressing room wasn’t a bodybuilder, but that didn’t detract from the frank hostility and meanness of her gaze.

“Strip,” she instructed.

Lisa peeled off the smartsuit supplied by the Swindon police. She braced herself for yet another dose of censorious advice about her style sense, but was pleasantly surprised for once. The one-woman reception committee gave her naked body the once-over with some kind of sweeper before handing her a brand-new outfit. It was a smart, dark-red one-piece, far more expensive and stylish than anything she’d ever have dreamed of buying. Had she not been so ruthless in excising all twentieth-century cliches from her vocabulary, it would have made her feel like mutton dressed as lamb.

The woman to whom she’d given her old one-piece took it away. It was another, even younger woman who came in to peel back the carpet, exposing the trapdoor set in the floor of the room.

“You got me dressed up like thisand you want to take me down into the sewers?” Lisa asked, feigning astonishment.

“You can walk through a sewer in a Salomey outfit and come up as lovely as a bird of paradise and as fresh as a golden rose,” the woman told her, straight-faced. “It says so in our catalogue.”

“That’s a relief,” said Lisa as she lowered herself into the opening, searching with what seemed to her to be stockinged feet for the rungs of the ladder. “In my day, birds of paradise still existed in the wild, and freshness standards were set by daisies—but everything’s artificial these days.”

It transpired, however, that the well beneath Salomey did not lead to the sewers at all. It led to a dimly lit, stone-clad tunnel that extended in a southeastern direction. To begin with, the tunnel was conspicuously clean and obviously new, but its storeroom-lined walls gave access within a hundred meters to brick-lined spaces of an ancient cast.

Lisa remembered the days when permission had first been granted for the construction of the mall, and she tried to recall the controversies that had raged around the project. There had been a convent on the north side of North Parade Road, she remembered. Deconsecrated and sold off by the cash-strapped Church Commissioners, it had briefly become the site of a rescue dig by archaeologists from the university before its crypt had been abandoned as a supposedly untouchable enclave within the stockholding cellars. Once out of public sight, the place had obviously fallen prey to the combined forces of economic convenience and the new privacy.

“The crypts of a nunnery overlaid and overlapped by a shopping mall,” she said to her guide. “You brought Morgan Miller to face the feminist inquisition in the cellars of a bloody nunnery.” This, she thought, was a decision that had Arachne West’s stamp on it.

“Quiet,” her guide instructed, although the command was pointless. If Lisa had still been carrying some kind of bug, the people listening in to it wouldn’t have required any verbal cues to help them figure out where she was.

The doors in the various sections of the cellar complex were far more modern than the brickwork that contained them, and they bore fancy combination locks. The guide conducted her through two of them before coaxing open a third. She waited outside to close it again once Lisa was inside, but Lisa wasn’t entirely convinced of the impregnability of the inner sanctum to which she was admitted. There was probably more than one way in, and there were probably too many people who knew the codes.

There was no sign of ancient brickwork inside the cosy cell. Its walls had been coated with some kind of artificial plastic, a pale green in color. Against one wall there was a semicircular desk; its generous size took up slightly more than half the available space, effectively reducing the rest to the status of a short, curved corridor. There was yet another inner room on the far side, similarly secured with a certified-unhackable double lock.

There was no one seated behind the desk to monitor the various screens mounted therein, but Arachne West was sitting on top of it. She was still bald, of course, but now that she was in her late forties, the baldness looked almost natural. What didn’t look natural was the velvety-black Salomey outfit she was wearing. It should have been highly polished synthetic leather, Lisa thought, or some kind of paramilitary uniform. Arachne wasn’t so much mutton dressed as lamb as lion dressed as kitten, but the effect was just as false.

“My mother always told me it was dangerous to talk to policemen,” the Real Woman said, “but kids never listen, do they?”

“The advice was bad,” Lisa told her. “You should have ignored it entirely. Where’s Helen?”

“I told her she ought to try to make a getaway before she’s installed on top of the ‘Most Wanted’ list. It was good to have the excuse—she’d become a liability since we had to make it clear to her that she wasn’t running the show anymore. So why was Mama’s advice bad?”

“If you’d come to me when Stella and Helen first persuaded you that Morgan had something worth stealing,” Lisa told her, “we could have avoided every sad act of this ridiculous farce. I could have talked to him for you.”

“You’d been talking to him for thirty-nine years,” Arachne pointed out. “I was on your side to begin with—I thought Stella and Helen might be letting personal matters affect their judgment—but in the end, I didn’t think I knew you well enough to know for sure which side you’d be on when the chips were down. You never let me get that close. You always kept me at arm’s length.”

“I was never convinced that you didn’t have designs on my body,” Lisa said. “What clinched the crazy deal? What’s this proofStella thinks she has of my complicity with Morgan’s allegedly unholy schemes? You must have figured out after you bugged my belt that I don’t know a damn thing.”

“You had your ovaries stripped, and the eggs frozen,” the Real Woman told her unhesitatingly. “There didn’t seem to be any reason for you to do that unless you were in on Miller’s grand plan. Stella had her own account of why he gave up on the dogs, which seemed plausible enough to those of us who remembered the old ALF riots. Did you know that Helen Grundy was the social worker responsible for the woman convicted after the riot at the East Central campus way back in ’15? Do people still say it’s a small world, or is that too twentieth century? Pure coincidence, of course—but that’s the whole thing in a nutshell, isn’t it? If you stick around long enough, the coincidences accumulate. Nobody can tell anymore what’s significant and what’s not. Once the dogs were off the menu, Stella said, Miller had to use mice or human embryos. She reckoned that your eggs might be supplying him with raw material as well as giving you the chance to save up for the big payoff. As for the bugged belt—you might have been running a double bluff. People who know they’ve been tagged can turn the leak to their own purposes, if they’re clever enough. You’re a cop, after all. You’re paranoid, I’m very paranoid, Stella and Helen are extremelyparanoid. When the whole world turns paranoid, everybody begins to see things that aren’t there—especially conspiracies.”

“But you, Helen, and Stella really are a conspiracy, aren’t you?” Lisa pointed out. “How many others are involved? At first I thought eight or ten, but now I’m beginning to think forty or fifty.”

“You have to fight fire with fire,” Arachne West informed her solemnly. Beneath her slowly fading musculature, there seemed to be a twentieth-century thinker—but how could that be, when Arachne wouldn’t have been more than eight or nine years old when the century turned?

Maybe, Lisa thought, it’s the century itself that won’t die, having embedded its cliches far too deeply in the very fabric of social thought. On the other hand, perhaps the people who lived in twentieth-century England spent just as much time berating themselves and one another for a host of leftover Victorian attitudes that weren’t at all what they seemed to be.

“We’re wasting time,” she pointed out.

“I know,” the Real Woman replied. “Sometimes I think that’s all we’ve done for the last twenty years while everyone just waited for the war to break out. Now it has—and are we ready? Are we hell?”

Lisa knew that the “we” in question wasn’t just the two of them, or the Real Women, or the entire population of radfemdom, and it might even include a few males of the species.

“According to Leland, private enterprise is ready,” Lisa told her. “Whatever containment measures the commission finally recommends will be irrelevant. The lovely people who brought you the kind of fabrics you ‘could wear in a sewer and still come up as lush as a golden rose’ have their new season all planned out. Suits that protect you from the plague—in all its myriad forms—will be the next big thing. You don’t have to contain the evil germs if the people can contain themselves. You needn’t worry about hidden eugenic strategies, though. Private enterprise will sell to anyone, provided they have the money. And who doesn’t, when it’s your money or your life? There may yet be a little worm in the bud, unfortunately.”

“What worm?”

“I didn’t have time to get the whole story, but Chan’s already tested some kind of versatile antibody-packaging system in the only kind of context that really counts. It didn’t work. Maybe the suitskin system will screw up. You can never change just one thing, you see, and you can never tell how far the unanticipated consequences will extend.”

“Stella told us about the war work Miller was doing for Burdillon,” Arachne admitted. “She thought that was what had finally persuaded him to give up on the other thing.”

“Can I go in now?” Lisa asked. “I’d rather like to get it over with before the guys break down all the doors and start blazing away in every direction.”

“He really didn’t tell you anything at all, did he?” the Real Woman said wonderingly. “And you never thought to go digging, the way Stella did. You could have winkled it out forty years ago, if you’d only thought to look. Lisa the policeman, scourge of all the murderers and Leverers in Bristol, overlooks the crime of the century on her own doorstep! What a fool you must feel.”

“Okay,” Lisa conceded ungraciously. “I’m a fool. It’s way past time to repair my sins of omission. Do I get to see him now?”

“Be my guest,” the bald woman said tiredly. “You’d better change his dressing before you start, though. The anesthetic’s probably worn off and you won’t get much out of him while he’s all racked up. That was Helen’s idea—but if and when the time comes, I won’t be trying to duck responsibility on the grounds that I was just an innocent bystander.”

Arachne’s tone had changed. The last vestiges of graveyard humor had vanished. Her pale eyes were still locked on Lisa’s stare, but it wasn’t a competition. The Real Woman knew how badly this whole operation had screwed up, but she wasn’t looking for a way out. She was just seeing it through to its end.

Lisa accepted the medical kit and water bottle that Arachne hauled out from behind the desk, along with the smartcard that would complete the deactivation of the inner room’s locks, provided the code numbers had already been loaded.

“I hope it isn’t too painful,” the bald woman said. “Unlike the loose cannon, I never had anything against you.”

Lisa wasn’t certain whether Arachne was talking about the sight that would greet her when she passed through the door, or the truth that would finally be told once she got to interrogate Morgan Miller.

“I can take it,” she said, figuring that the reply would do in either case.

Arachne West swung her sturdy legs over the desk and slipped into a seat behind one of the screens. Lisa had no doubt that it was a position from which the Real Woman would be able to see and hear everything that transpired in the cell where Morgan Miller was confined. She didn’t mind. There had been far too many secrets for far too long. It was high time that everything was brought out in the open.

She passed the smartcard through the swipe slot, and the door obligingly clocked open. She went through it and closed it behind her.

It was as if she were closing the door on all sixty-one years of her carefully accumulated past.

TWENTY-ONE

The cell was gloomier by far than the anteroom. The bare brick had been carefully preserved here in all its brutal simplicity. The temperature seemed to have dropped by five degrees as Lisa crossed the threshold.

Morgan Miller was lying on a tubular-steel foldaway bed not unlike the one in which Leland had installed Stella Filisetti. He wasn’t secured to the frame by smart cords, but that was because he wasn’t in any condition to do anything as stupid as attacking his captors. The sleeve of the unsmart shirt he was wearing had been ripped from shoulder to cuff to expose his right arm, which was folded very carefully across his chest, exposing a long series of burns that looked as if they had been etched by a blowtorch. Some kind of dressing had been applied to the wounds, but the synthetic flesh hadn’t been able to bond properly. It had mopped up blood and other fluids that had leaked from the wounds, but its capacity to metabolize them had been overloaded. Even its painkilling capabilities had been overstretched.

When he first caught sight of Lisa, a hopeful gleam came into Morgan’s eyes, but it dwindled almost immediately to a mere ember of endurance. Even the benign mental chemistry of hope could be converted by injury into a source of pain.

Lisa knelt beside the bed and opened the medical kit. She drew off the useless pseudoskin as carefully as she could—not quite carefully enough, to judge by Morgan’s ragged breathing—and substituted a generous helping of gel. Only then was Morgan able to open his eyes again. He seemed to have been utterly drained of all physical resources—a considerable indignity for a man who had fondly imagined that he was as fit as a flea. It was an effort for him to raise his head and take a few sips from the plastic bottle.

“Shit, Morgan,” Lisa murmured. “Why didn’t you just tell them what they wanted to know?”

“What kind of fool do you take me for?” he whispered as he let his head sink back again. “I told them everythingbefore they even turned the flame in my direction. I told them the absolute truth—but they wouldn’t believe me. I found out a couple of hours too late that the only way to deal with torture is to tell the fuckers what they want to hear, not what they want to know.”

“Shit,” said Lisa again. She had never felt so helpless.

“I toldthem you didn’t have anything to do with it,” Miller said, urgency raising his voice. “They weren’t in a mood to take my word for anything. If I’d said that two plus two was four, they’d have got out their calculators.”

“It’s okay, Morgan,” Lisa said. “I’m here of my own free will. I came as soon as I figured out which of my old friends and acquaintances were involved. The cavalry won’t be far behind. The farce is almost over. Arachne’s people were panicked into precipitate action, but they’ve calmed down now. We’ll be okay.”

“It was a mistake,” Morgan said. “That little fool Stella guessed half the story and didn’t have the imagination to look for the twist in the tail. I told them the truth, but they started burning me anyway, and they kept right on no matter what I said. I had to try something else, and when that didn’t work … by then, I wasn’t in any condition to come up with anything they might find convincing. I tried, but…”

“It’s okay, Morgan.”

“They still won’t believe it, Lisa. Your being here won’t make any difference. They won’t believe that I did what I did for the reasons I did it. They’re too paranoid.”

“There’s a war on,” Lisa reminded him. “The fact that the government won’t admit it yet only makes it that much more terrifying—and the fact that the MOD is ten or twenty years behind the new cutting edge of defense research doesn’t help. If you know why Chan’s versatile-packaging system was a nonstarter, you’re in a better position than I am to guess whether the new systems will fare any better, but the likes of Helen Grundy and Arachne West don’t have any reason to believe that they’re high on anyone’s list of defense priorities. They’re entitled to their paranoia—and it wasn’t just Stella’s prying that made you into a plausible target. You should have told me, Morgan. This farce has trashed my life. All the gray power in England couldn’t save me from the scrap heap now. Whatever it is, you should have told me.”

“I know that now,” he said. He was speaking a little more comfortably; the painkillers administered by the smart dressing had restored what remained of his equilibrium. He was even able to raise his head from the pillow again and prop himself up on his left elbow. “The smartsuit’s a mistake, though,” he added. “It’s nice, but it’s not your

“You wouldn’t know,” she said bitterly. “So concentrate on what you do know. Stella and Helen might not have been able to recognize the truth when they heard it from your lying lips, but I can. Tell methe truth. Explain to me how come I’ve known you for thirty-nine years without ever being able to see what a sly hypocrite you are.”

“I’m truly sorry,” Morgan said, letting his voice fall to a whisper again. “But Chan was right about that, if nothing else. You were a police officer. It wouldn’t have been right to let you in on anything that would have compromised your integrity. Maybe it was only a technical offense, but it was an offense nevertheless. You were so entranced by that stupid experiment that I was never sure of how you’d react to the news that I’d already subverted it. As time went by, it became harder and harder to confess that I’d been keeping the secret for so long. I never told Chan either—and he was too trusting to ever suspect that the real reason I wouldn’t let him introduce his experimental mice into two of the mouse cities was that I’d already introduced mine into London and Rome. Anyway, there really are secrets so nasty that the only safe place to keep them is the one between your ears.”

“But you offered to give it to Ahasuerus and the Algenists. You couldn’t trust Chan or me, but you could trust Goldfarb and Geyer?”

Morgan sighed. The furrows on his brow bore witness to the force with which her arguments were striking into his conscience. “It’s science, Lisa. It was always a matter of time. Eventually somebody else was bound to come up with the same gimmick, with the same built-in mantrap. I spent forty years trying to iron out the bug– forty years, Lisa. I wasn’t prepared to let it out with the two sides of the coin so tightly welded together. I wanted to knock out the defect first—but I never could. I had to pass the work on to somebody else. I might have given it to Chan if he hadn’t become so heavily involved with Ed’s defense work, but the one thing I daren’t risk was handing it over to the MOD while the whole world was gearing up for war. If peace had ever broken out… but you and I know well enough that there’s alwaysbeen a war on, and always will be till the big crash finally comes. I thought that if I could just figure out how to eliminate the downside, it would all be good … and it seemed so simple, so … Lisa, you have no ideaof how sorry I am. I thought I could straighten it out, but all I did was fuck it up. I had no idea it would take forty years, and if I’d ever dreamed that forty years wouldn’t be enough…”

“Pull yourself together, Morgan,” Lisa said, surprised by her own coldness. “Anyone would think you were still under torture. Just tell me the truth, from the beginning. I don’t know anything, remember—and like poor little Stella, I still can’t figure out why even a misogynistic bastard like you would want to keep a longevity treatment quiet just because it only works on women.”

Morgan actually contrived to laugh at that. “If that’s all you’ve figured out,” he said, “I can understand why you’re so pissed.”

“So tell me all of it,” Lisa said impatiently.

“Okay,” he said, settling back onto the pillow. “Here goes– again.It started in 1999, three years before I met you. It was locked up tight in my skull before you ever clapped eyes on me, and it would have taken a lot to break the seal, so don’t be too hard on yourself for not being able to. The production of transgenic animals was in its infancy then—even sheep could make headlines. Almost all successful transformation was done mechanically, using tiny hypodermics to inject new DNA into eggs held still by suction on the end of a micropipette. It was ludicrously inefficient, and everybody knew it was just a stopgap, that some kind of vector would soon be devised that would make the whole business cleaner and sweeter. Viruses were the hot candidates—nature’s very own genetic engineers. The first mass transformations of eggs stripped from bovine wombs in the slaughterhouse had just been carried out with retroviruses, so everybody knew that it was possible, but we needed viruses that were better equipped for the job than anything nature had. Nature’s viruses have their own agenda, and a talent for turning nasty. Everybody with an atom of foresight knew in 1999 that it was only a matter of time before artificial viruses could be developed that would specialize in our agendas, but nobody knew for how long … and that was only half the problem.

“It was difficult in those days to build up self-sustaining populations of transgenic animals. Cloning technology was in its infancy, and experiments with sheep, cattle, and pigs were limited by the long life cycles of the animals. In 1999, the vast majority of transgenic strains were mice, simply because mice have such a short breeding cycle. They were the only livestock we had that was prolific enough to allow us to use the bacterial engineer’s favorite tactic—transform a few and kill the rest. Plant engineers were still shooting new DNA into leaves from guns, selecting out the few dozen successfully transformed cells from the thousands that were destroyed or unaffected with herbicide, then cloning away like crazy—but you can’t regenerate a whole animal from a handful of cells, and even if you grow a transgenic animal from a transformed egg, you still need another exactly like it to mate it with before you can start a dynasty. Sex—the root of all the world’s frustrations—was the animal engineer’s great stumbling block.

“Mice were a lot more convenient to work with in ’99 than anything bigger, but they were far from perfect. The process still took too much time, and it was all very hit-and-miss—but when I read about the mass transformation of bovine ova by retroviruses, I figured it was a method that could be taken to its logical extreme.”

He paused, but Lisa wasn’t about to play guessing games now that the tale was underway. She contented herself with a mere prompt. “Which was?”

“Well, I figured that if you could transform eggs stripped from a slaughterhouse organ, you ought to be able to transform them in situ—in the ovaries of a living animal. At first I figured that the best kind of living animal to use was a fetus—because eggs, unlike sperm, aren’t produced continuously throughout an animal’s lifetime. By the time a female animal is born, she’s already lost most of the egg cells she had when her tissues first differentiated, and she keeps on losing them before and after she reaches puberty. Not many animals survive to menopause, of course, but humans display the far end of the spectrum. A woman your age has no viable eggs left at all, having lost all but a tiny few before she ever reached breeding age.”

Unless, of course, Lisa thought, she had her remaining stock taken out while she was in her twenties and stored in liquid nitrogen.

“What I tried to do,” Morgan went on, “was to introduce retroviruses into pregnant mice, aiming them specifically at the eggs within the fetal ovaries. The idea was to secure a vast collection of ready-transformed pre-oocytes, which could then be extracted from the aborted fetus. It would have been authentic mass production, on a time scale measurable in days rather than weeks, let alone the years it takes to bring transformed sheep and cows to adulthood. You can see what a boon a system like that would have been to my search for the ideal addressable vector.

“Unfortunately, it wasn’t as easy as it sounded. Nature’s genetic engineers are unreliable slaves—they have their own agendas, and a lot of those agendas are what the man in the street calls diseases: colds, colics, and cancers. The womb has it own agenda too. It has a system programmed into it, and when you have wombs within wombs, things can get very complicated. I couldn’t get effective transmission across the placenta. I had to switch my attention to newboms, although it seemed like a terrible waste. So many eggs have already gone by the time a mouse is born, and the rest are dying in droves day by day. I thought it might at least be possible to do something about the latter problem, so I modified my retroviruses yet again, incorporating a control gene that was supposed to stop the oocytes from committing suicide.

“That one worked. In fact, it worked far better than I’d hoped. In coupling it with the rest of the package, I’d somehow contrived to produce a synergistic effect—one of those million-to-one shots of which I’d always been so flagrantly contemptuous. When you have a hundred thousand genetic engineers trying out hundreds of novel gene combinations every year, though, the laws of probability will give you a million-to-one shot every month. Mine was the only one I ever got in forty years of trying, but it was a big one.

“In those days, we were only beginning to get used to the first principle of genetic engineering—you can never do just onething—so I hadn’t figured multiplicity of effect into my plans, let alone synergy, but they sure as hell came out in my results. Do you ever come across genetic mosaics in your police work?”

“Occasionally,” Lisa confirmed. Mosaics had first attracted attention when biologists contrived to fuse the embryos of two different species. The first sheep/goat hybrids had been produced in the 1990s, and the revelation had prompted people to wonder how often the same thing happened in nature. Whenever a single fertilized egg divided into two to produce identical twins, the result was obvious, but when two fertilized eggs fused to produce a single individual, there was no easy way of telling that the resultant individual was a mosaic. Until DNA analysis came along, there was no way of knowing how many cows in the bam or people walking the streets were actually patchworks of two distinct but closely related genomes. Human mosaics were even rarer than pairs of identical twins, but a world of nine billion people had to contain millions. Lisa had run across half a dozen human mosaics while conducting DNA analyses in the police lab.

“In that case, you probably know that animal mosaics were often created mechanically back in the 1990s. It was an early alternative to cloning that lost fashionability when nuclear-transfer techniques improved. The mosaics I created with the aid of my trusty retroviruses were a kind that nature had never contrived, though. My retroviruses produced a strain of mice whose egg-filled ovaries became benign cancers—not merely benign in the accepted sense that the cancers were harmless, but in a much stronger sense. The transformed eggs became capable of fusing with one another to produce zygote-like bodies that then began to grow, but not like fetuses, and not like commonplace tumors. What they did was to emit a slow but steady stream of new stem cells that could be—and were—distributed throughout the body and gradually integrated into the organs of the mothers. The mothers became, in consequence, a complex mosaic. Their complexity didn’t show up readily in the kinds of DNA analysis that Ed and I taught you to do, because the sum total of all the pesudezygote types was delimited by the original female genotype. I didn’t figure out exactly what was happening for quite a while, and I might have missed it altogether if I hadn’t started working with newborns, but that made it obvious enough that something very weird was happening.