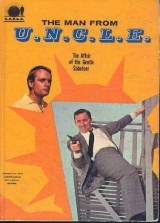

Текст книги "[Whitman] - The Affair of the Gentle Saboteur "

Автор книги: Brandon Keith

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 6 страниц)

11. "Mistake in Judgment"

ALL WAS READY, all prepared. Burrows' message came through sounding hollow in the speaker. Tudor switched off the receiver, went out to the helicopter on the beach. Pamela Hunter, rehearsed as an assistant in murder, waited in the house. Thirty minutes! And she was to be the greeter, the hostess. Stanley would proceed at once to the helicopter; she and Burrows would escort Solo to the concrete room. That's why she was in the house—to keep Solo placid, unsuspecting. She was young, a young girl, she would be smiling and gracious. He could not possibly conceive that she was the decoy leading him to death. Once Solo was locked in, Burrows would do the rest; then the panel in the iron door would be slammed shut. Smooth and simple, uncomplicated—and horrible!

Thirty minutes! She lit a cigarette, her fingers trembling. It was cool in the air-conditioned room, but her palms were wet and sticky and her mouth was dry. She tried to reason with herself, tried to shut the present out of her mind. Soon, soon, thirty minutes, and it would all be over; she would be with the others in the helicopter flying swiftly to safety.

Safety! What safety is there against oneself? What helicopter can fly you away from yourself? How can you live with yourself for the rest of your life knowing, knowing...?

She fought in her mind. She was a soldier. No! Yes! But in the wrong army—she knew that now, finally. She had been recruited, enticed by sly words, drawn in by fine-sounding phrases, slogans, speeches, all empty, untrue, enticements to ensnare her. What soldier in what army? What army entraps an innocent seventeen-year-old and murders him? He was no soldier in any army, nor was she!

The truth struck now like a tremendous gong. She was not a soldier but a mercenary, a paid professional. She was not a part of an army but a member of a world organization of professional criminals, covering their crimes by a pretense of political activity, earning huge sums of money as the lackeys, without conscience, of governments that desired unrest and world turmoil. And she had become one of them, lured by the lower echelon of their experts, the speechmakers, the lecturers with their high-flown slogans. And now there would be no turning back. Crime is its own trap. The blackmail of one crime compels the next; she would be forever committed.

No! Perhaps she could not save Solo. Perhaps she could not save herself from whatever punishment the American authorities would mete out to her, but she could save herself from herself! She could be free again, out of the trap, her conscience clear; free, her own self again, not hating herself, not cringing looking into her eyes in a mirror; free, remembering her blithesome nature; free, remembering her old happiness; free, no matter what her penalty. Free!

She hurled the cigarette into an ashtray and fled down the stairs to the basement. Breathlessly she tugged at the bolts of the iron door—three wide slide-bolts, top, middle, and bottom—and pulled with all her strength at the heavy door. It opened, creaking.

Mr. Kuryakin and the boy stood in the middle of the room, looking at her. They needed shaves. The clothes provided them fitted badly. Pale, untidy, unkempt, they looked rough, dangerous, like tramps, this man from UNCLE and this son of the British Ambassador to the United Nations. Wanting to cry, blinking, biting back hysteria, she laughed—and stopped it, feeling her teeth against her suddenly stiff lips.

"Come!" she whispered, realizing there was no need to whisper, for they were alone in the house.

Kuryakin frowned, standing still, holding back, studying her.

Softly but quite distinctly he said, "What is it?"

"Come! Please! Quickly!"

Still he stood his ground, persisting. "Why?"

"They—they want to—they want to kill you." It was as though his study was completed. His grin was boyish, his blue eyes crinkling at the corners. He slapped an open palm at the boy's rear, like a coach sending in a football replacement. "They want to kill us, the lady says, the beautiful lady." He slapped again quite casually, cheerfully, but his voice was tense. "Get a move on, Stevie boy. Don't let's keep our lady waiting."

She led them up and out through a side door, and they were in the hot sunshine under the blue cloudless sky.

"This way." Still she was whispering. She could not help herself.

They hurried, a little group, a long way through shady, sweet-smelling orchards and then in the blazing sun along the tended grass of wide lawns and then in the coolness of shady trees again. She led them a long way westerly, until they came, by a narrow path, to a little side-gate in the high, iron picket fence. The lock was a combination lock, and she twisted and turned the circular indicator, whispering the numbers, left, right, right again, left, right, right and right, left, and right.

She pulled down and there was a click and the lock opened and then the gate opened and she led them under the hot burning sun a long way along narrow roads. Then they were on a big road and cars passed and they waved at the cars and the cars passed.

"Look," Kuryakin said. "Steve and I better get out of the way. We look like a couple of hoods, delinquents. I don't blame them for not stopping." And he grinned. "But for you, Miss... Hunter, did you say?"

"That is correct."

"Anybody doesn't stop for you, Miss Hunter– that would be a pretty sick fella."

They went off the road and squatted behind a hedge of weeds and were out of sight of the whiz zing cars. The girl stood alone, a blond girl in a green-and-white striped dress, and waved at the whizzing cars. A truck stopped, and she talked to the driver. Then she turned and waved to them, and they came out of the shelter of the weeds and went up into the truck, and they all sat huddled together in the steamy cab of the truck thunderously rumbling on the hot road.

"I'm not allowed no riders," the driver said, a round-faced man in a visored cap, "but the little lady says emergency, and emergency, naturally that's different. But I am dropping you off at the first town, which ain't far, which is the deal I made with the little lady, which is all I can do for you. I'm not allowed no riders."

"Thank you," Kuryakin said.

"Ain't much of a town. Three blocks of town and then no more town. All the rest all around is suburbs for rich people."

They rode rumbling in the sun for a few miles, and then the truck stopped at the edge of a paved street.

"This is it," the driver said. "All I can do. I can get into trouble. I'm not allowed no riders."

"Thank you," Kuryakin said.

"Welcome. Watch your step, little lady."

The truck was gone, leaving a smell of gasoline in the motionless air. They walked and came to a diner, built in the shape of a railroad car, painted yellow. Now it was Kuryakin who was leading. They climbed up three stairs, slid open a door, and entered. It was an off hour; there were no customers. It was cool from wood-bladed fans slowly rotating from wooden staves in the ceiling. There was a counter with backless round-seat stools screwed into the floor. Opposite the counter there were booths by the windows. The windows had Venetian blinds drawn against the glare of the sun. It was dim and cool and empty.

A woman in a yellow uniform with a lacy white apron came out from the kitchen behind the counter, took up a pad and pencil from the counter, looked rather suspiciously at Kuryakin and Steve, but smiled toward Pamela Hunter.

She had a long face and long teeth and narrow inquiring eyes. Her voice was not friendly, but neutral.

"Yes, folks? What can I do for you?"

Kuryakin smiled, nodded, and said, "Please, a minute," and the three huddled. "Do you have any money?" Kuryakin asked Pamela. "We don't."

"No. I didn't bring a bag. Nothing." Kuryakin broke from them, went to the woman behind the counter.

"We don't have any money, ma'am, but if you please... ."

"What the heck's going on here?" the woman said, fear pinching in her mouth. "What is this?"

"Please, we don't mean any harm. We're in a bit of trouble."

"Look, I only work here. I can't serve you..."

"Could you lend me a dime, please, for a phone call?" Kuryakin pointed toward the phone booth at the far end of the diner. "A call to New York..."

"That costs more than a dime, mister."

"I'll call collect. I'll return the dime to you at once."

"What the heck's going on here?" She looked from the unshaven men to the well-dressed girl.

"These guys bothering you, miss? I mean..."

"No."

"You with them—or they forcing you into something?" Her voice pitched up shrilly. "Just don't you be afraid, dearie..."

"No, I'm with them."

"What the heck? Now what the heck is this? Something's darned funny..."

"Please give him the coin. Please!"

"Darned funny. Who are these guys? You sure you know them? Look, we got cops..."

"I know them."

"You in trouble?"

"Yes. All of us."

"Look, honey, if you're hungry, it's okay. I don't own this joint, but grub, a meal, I can stake you..."

"Not hungry, thank you."

"You sure?"

"Sure."

"Honey, I don't like this. Look, we got a kitchen man in the back. He's big; he can take these two guys and knock their heads together. Don't be afraid now. I can see you're afraid. You got tears in back of your eyes, I can see. Now just hold up. William!" she called toward the kitchen. "Hey, Bill!"

A towering man in a white apron came out of the kitchen and out from behind the counter. "Okay, I been listening. I'll take care of these bums, lady. I'll throw them right out on their ear." He took hold of Steve. Kuryakin pulled him off. The man clenched a huge ham-hand, turned swiftly, hammered the hand at Kuryakin. Illya ducked and jolted a fist upward, in a short thrust to the man's jaw. Abruptly the man sat down on the floor.

"No. No!" Now Pamela was crying. "Please, no!"

The man sat on the floor, blinking.

The woman behind the counter held a kitchen knife menacingly.

"Please! Please!" Pamela cried.

Kuryakin helped the man to his feet. "Sorry."

"You sure pack a wallop, young fella," the man said, rubbing his chin. "Give him the dime, Esther. This is no bad one. Bad, he could have kicked me in the head while I was sitting down there. He could have kicked my brains in. Instead he picks me up and says he's sorry. Well, I'm sorry, young fella. Mistake in judgment. Takes all kinds. It's a crazy world. Give him the dime, Esther."

The woman put down the knife and rang the cash register.

Kuryakin accepted the coin and went to the phone booth and closed himself in.

12. Change in Plans

AFTER BURROWS' CALL to Solo, Sir William Winfield had routinely called his office and had been advised of urgent business. The British Ambassador to the United States and the Japanese Ambassador were flying in from Washington for a conference with Sir William; they would be in his office in the UN Building at ten-thirty that morning and would remain for lunch with Sir William. He, of course, confirmed the meeting. His son was missing but UNCLE was actively engaged in it. There was no assistance he himself could provide. Waverly had put his own car and chauffeur at Sir William's disposal.

"You know the arrangements," Waverly had said. "The first contact is one o'clock. After that, who knows how long it will take? I'll be in communication, by telephone, with my car as soon as anything breaks. My chauffeur, Ronny Downs, beginning at one o'clock, won't leave the car. You keep him informed where you'll be. If there's any news, I'll get through to him, and he'll get through to you. When your business is completed, come down to the office and you and I'll sit out the vigil together."

Sir William had left the UN Building at one-fifteen.

"Anything?" he had asked the chauffeur.

"Nothing, sir."

He had gone home, spent a half-hour with his wife; he had been glib and cheerful, pretending assurance, encouraging her about Steven; then Downs drove him to UNCLE headquarters.

Waverly was alone when Sir William entered. Green blinds were drawn to keep out the sun; Waverly was slumped in his chair at the desk, smoking.

"Sit down, Sir William."

"Thank you."

Waverly smiled glumly. "The contact's been made."

"How do you know?"

Waverly laid away his pipe. "Stanley and Mr. Solo went off alone as Eric Burrows instructed, but five cars at safe distances went along with them not as Eric Burrows instructed."

"I—I don't understand."

"Our lab introduced certain substances into Mr. Solo's body that give off an electronic signal. Special computers in the cars indicate precisely where and what distance he is from them. The men in the cars are in communication with me." Waverly pointed to an oblong box on his desk. "This is a lovely instrument, a sender-receiver meshed with the sender-receivers in the cars; the synchronized wave bands automatically change every thirty seconds. Thus, if by chance a conversation is intercepted, a listener can hear only a thirty-second fragment."

"The cars are out of sight?"

"Far out of sight."

"Then how do you know about the contact?"

"Mr. Solo with Stanley came to the intersection of Savoy and Remington at approximately one o'clock; that the computers were able to pinpoint. On Remington Road the car was abandoned, and they walked."

"But how...."

"The electronic signal emanating from Solo. The rate of speed of his movements can be computed. He walked, presumably with Stanley, for about a half-hour. During this time, one of our cars spotted Solo's abandoned car—didn't touch it, of course. Then, oh, about twenty minutes ago, the rate of speed accelerated again. They were picked up by a moving vehicle. And that's about how it stands right now."

"My son?"

"Not yet."

Waverly lifted a lever of the oblong box. "Alex here, calling Number One. Come in."

McNabb's voice was clear. "They're still moving at a fairly good clip. Number One, Jack and I, trailing. Number Two a half-mile behind us. Three, Four, and Five are fanned out on other roads. No significant stops since he entered the moving vehicle. No hits, no runs, no errors—nothing. All smooth, no change."

"Check." Waverly depressed the lever. Sir William was sitting forward, his hands clasped so tightly the knuckles were white. "So far, so good," Waverly said. "Please relax. So far it's going exactly to specifications, and my people are instructed not to interfere, to take no risks. Our object is to effect the exchange without putting the hostages in any possible jeopardy. We hate losing Stanley, but the welfare of your son and our Mr. Kuryakin is paramount."

"But—all this time...?"

"According to specifications, Sir William. Burrows—and we can't fault that—was being careful. He set the rendezvous a good distance from the point of destination. We can't blame him for that, can we?"

"No, I don't suppose..."

"And even before the rendezvous—he let them walk for a good half-hour on a country road, observing them from somewhere, I'm certain—making sure they weren't being followed—that we were proceeding in accord with his instructions. All of that is good rather than bad, Sir William. I appreciate your concern. Your son—"

The short sharp jangle of the phone startled him. He had left orders at the switchboard that he was not to be disturbed unless it was a matter of extraordinary importance. He pulled the receiver from the cradle and said curtly, "Yes?"

Sir William watched as the Old Man straightened tall in his seat.

"Yes... yes... um... I see." The color was up in Waverly's face; in the dim, shadowy green of the sun-subdued room his eyes sparkled with dancing lights. "Yes ... yes ... all right. Now hear me. Stay just where you are. Just stay there! They'll pick you up. 'Bye now." He hung up, turned a smile to Sir William. "Your boy is safe!"

"Are you sure?"

"Absolutely."

"Thank goodness!" Sir William was on his feet, his hands spread on the desk; he leaned across to Waverly. "But what—how...?"

"Listen!"

Waverly flipped the lever of the oblong box.

"Alex here! Number One! Come in!"

"You're loud and clear, Chief," came the voice of McNabb.

"Hold sharp! We've got a shift in operation!"

"I hear you, Chief. Go!"

"Defection. The girl. I don't know the details. The boy and our boy are out, along with the girl. Initials P.H."

"I read you. Go!"

"They're in a restaurant called Pullman Diner in a town on the North Shore called Carbonville. Have Numbers Three, Four, and Five go directly and pick them up. Now!"

"I read you! So do they! We're all tuned in!"

"Change in operation, Mac. No more exchange. Bring back A.S. Stay in communication, all of you—among yourselves, and all of you back to me. Hear?"

"Check! We all hear!"

"I'll keep this thing wide open! Talk, any one of you, whenever you want to!"

"Check!"

Waverly slumped back in his swivel chair, looked up to Sir William. "Before, there was a faint possibility of trouble. Now it's for sure." He reached out, clicked shut the lever on the oblong box, and sighed. "But McNabb's a sturdy old bird. He'll keep the young ones in rein. You and I—even older birds—all we can do is sit and wait."

"Steve?"

"He's out of it now. Safe and sound."

"I thank you, Mr. Waverly."

Waverly grunted, clicked open the lever, and sat slumped in his chair.

13. "Two-Gun McNabb"

OUTSIDE, THE SUN glared hotly. Inside the gray Rolls, Solo was not uncomfortable. He was, in fact, cool. The car was air-conditioned, but not cold. Burrows had adjusted the thermostat after Stanley had reminded him that Solo was not wearing conventional clothes. He was a strange man, this saboteur. Aside from his work—which was exploding places and killing people—he was as kindly and considerate as a devoted grandfather. Once he had even had Burrows stop the car so that he could get a light blanket from the trunk in the rear for Solo's knees. It was as though, in the new circumstances, he was the host. He chatted with Solo, offered cigarettes, even a drink from a bar in the car, courteously; and as courteously Solo refused. The little man sipped brandy and chatted affably. It must have bored the man in front; he touched a button on the dashboard and the dividing window rose up, shutting him off from the two in the rear. He did not once turn his head; Solo's view of Burrows was black hair, the back of a thick, strong neck, and an occasional flash of a rugged profile.

But the view outside the car had changed. The Rolls now sped along a good-surfaced road; the landscape now had trees and bushes and rolling hills and fine houses deeply set in the hills. Once they passed a golf course with brightly dressed men and women at play, trying to escape the oppressive heat.

"Lovely countryside," Stanley said. "So peaceful, slumbering in the summertime. I adore a pleasant countryside. I paint, you know, in my leisure. Oil, mostly landscapes. Quite good, if I may be so immodest as to say; I've had several showings in London galleries."

Solo's eyes were hidden behind his sunglasses; Stanley could not see the amusement that crinkled the corners. "I don't get you," Solo said.

"What is there to get, Mr. Solo?"

"I mean—if I didn't know what you do..."

"One must not judge a man by the work that earns him his keep."

"But your work."

"It is work. One need not love one's own work; one may take pride, but not love. A long time ago, Mr. Solo, I was greatly respected—by respectable people—for just that kind of work. A long time ago, during a shooting war, I was a major in the British service; I was a demolitions expert." He shrugged his thin shoulders. "Quite natural, I would imagine, that peacetime people would gather in a wartime expert." He smiled a melancholy smile. "Expert! The expert failed here quite miserably, didn't he? You told Mr. Burrows I was spotted at the airport. Where at the airport, if I may inquire?"

"Customs."

"But I was only a salesman with a dispatch case that was utterly innocent."

"The dispatch case may have been innocent. But not you."

"But who would know me?"

"UNCLE is efficient, Mr. Stanley."

"We do not underestimate UNCLE, I assure you."

"Had you been as innocent as your dispatch case, you wouldn't have been molested. We would have loved to pluck you out of circulation—whether or not you made any wrongful move—but we don't work like that in this country. Instead, a heavy surveillance was put around you. The room next door to yours was ours, and we were in the lobby, and we were outside in the streets; the taxi that drove you to Liberty Island was ours."

The little man puckered his lips. "Clever, these Americans."

The man up front was talking into the microphone.

This time Burrows received no acknowledgment, but it did not disturb him. Tudor was probably out in the helicopter and the girl out front on the portico as a welcoming committee of one. For that, she would be valuable; psychology had its uses. A blond, shining, cherubic-faced girl did not present an image of a terrorist, an executioner; and it was best to keep this Mr. Solo placid.

Not that he could do any damage with all his lethal little gadgets lying useless in that clearing in the weeds, but it was best to keep him placid because time was of the essence, and UNCLE was not stupid. Certainly they were about—somehow—somewhere—and he, Burrows, was a veteran. Never play down the enemy, always expect the worst. They were somewhere about, but they could not risk, would not dare, an awkward interruption. They had two lives at stake, including one of their own valuable men—he himself would have been sufficient in exchange for Stanley– plus a boy whose death could produce international furor, the son of the British Ambassador to the United Nations.

No, they wouldn't dare; nevertheless, time was of the essence! If it went according to plan it would be over five minutes after their arrival—the concrete room, an accommodating Solo supposedly to be locked in for an hour, the cyanide pellet exploded in the concrete room, the slide-door snapped shut—and the four agents from THRUSH would be off and away in the aircraft and out of the country. All told, no more than five minutes—but keep Mr. Solo placid. A break in the smooth-flowing scheme, a Mr. Solo grown suspicious and balking, the waste of time in scuffling and physical persuasion, gunfire out doors—and the people from UNCLE might swoop in, no matter the risk.

The man up front put away the microphone. The Rolls turned into a wide private pathway of gleaming white pebbles.

"Are we there?" Solo asked Stanley.

"I don't know," Stanley said. "Believe me, I don't know where we're going. They don't tell me everything. I work under orders and try to do my job; that's all." He peered out the window with casual interest.

Solo watched with more than casual interest, sitting up straight now, tense, alert. The pebbled roadway was lined with tall green trees.

The Rolls rode up it perhaps half a mile. Then it stopped at high iron gates in a high picket fence—a black iron fence, high, very high, sharp spokes like knives pointing upward, razor-edge-sharp, malevolently gleaming in the sun shine, cutting, killing long points like the points of gigantic upthrust sabers, protective, forbidding. Beyond the iron gates the white-pebbled roadway continued, curving away.

The motor of the Rolls died to a silence. All was still.

Then Burrows got out, a black automatic pistol in one hand, a huge black key in the other, and stood outside the rear door. Stanley rolled down the window.

"Is this it, Mr. Burrows?"

"Well, what do you think? Out, gentlemen. Yes, this is it, Mr. Stanley."

They climbed out, and of the three standing on the white pebbles, Solo, in the swim trunks, was most appropriately dressed—it was blazing hot, the air like a thick blanket of heat. Appropriately dressed, but he wished he had sneakers. The white pebbles, like heated stones of torture, burned at his soles. He kept moving his feet, dancing a little jig as the bottoms of his feet tried to grow accustomed to the agony.

"Whew!" Stanley said.

Burrows tossed the key, and Stanley caught it casually.

The black automatic was pointed at Solo. "Why the weapon?" Solo said.

"To assure us you'll be a good boy," Burrows said.

"I'll be a good boy. What choice do I have?"

"No choice." Then Burrows, his eyes not leaving Solo, the gun leveled straight, said, "Stanley!"

"Yes, sir?"

"The key. You'll open the gate. After we pass through, you'll lock the gate. Then, on the right side, you'll see a switch. Pull it up, all the way. That'll electrify the fence all the way around. Anybody touches it, he's electrocuted."

"But we have an arrangement, don't we?" Solo asked.

"We do," Burrows said.

"Then why all the precautions?"

"To assure us the arrangement will be kept. Just one hour, Mr. Solo. When we notify the authorities to pick you up—you and Kuryakin and Steven Winfield—at that time we'll also notify them of the electrified fence." Then he added sarcastically, "Any more questions, Mr. Man from UNCLE?"

"No."

"Stanley!"

"Yes, sir?"

"Well? What are you waiting for?"

"Yes, sir."

Stanley inserted the key and turned the lock, withdrew the key, pushed, and the heavy gate swung inward noiselessly.

"All right," Burrows said impatiently, gesturing with the black automatic. "Move, Mr. Solo!"

"Don't tell me you're leaving the beautiful Rolls."

"Mind your own business. Get in there."

"Yes, sir," Solo said meekly, mimicking Stanley.

And then the roaring sound was upon them and they turned, all three, and saw the wildly racing car careening directly at them, and already Burrows was shooting. There was the sound of grinding glass but the bulletproof windshield did not shatter. The car skidded to a stop on the white pebbles, and two men were running out. Solo recognized them—McNabb and O'Keefe.

O'Keefe, a famed sharpshooter, held a huge revolver in his hand. He shot just once, and Burrows' automatic flew from his hand, and Burrows was running. O'Keefe, tossing aside the gleaming revolver, was running after Burrows, and McNabb—quite casually, slowly, almost tiredly, not even looking at the running men—picked up the black automatic and the silver-shining revolver. O'Keefe closed ground on Burrows and, leaping forward in a flying tackle, hit Burrows precisely at the knees, and the two fell to the ground with a thud. The struggle was brief. O'Keefe pulled Burrows to his feet, twisted Burrows' right arm behind his back, and, broadly grinning, brought the grimacing Burrows back to them.

"Not bad, hey?" O'Keefe said. "One shot and I knocked his gun out of action. And not even a scratch on him, not even a sideswipe; didn't wing him, not a nick on him. Now you just be good, baby," O'Keefe said to the squirming Burrows, "or you'll spoil the whole thing. I'll have to break your arm."

McNabb stood smiling like a tired gunfighter of the Old West, limply holding the pistols, his arms loose, the muzzles pointed downward. Two-gun McNabb of the wild, old, woolly West. Calmly, as though addressing a PTA meeting, McNabb said, "Don't you worry about Eric; he'll be good. Eric is a veteran campaigner; he knows when he's licked. Don't you, old Eric, old bean? Let him loose, Jack."

O'Keefe released Burrows. Burrows stood motionless, panting, chin down. "Two veteran campaigners," McNabb said. "Our troubles are over, Jack. Relax." McNabb gave the pistols to O'Keefe and unhooked a pair of handcuffs from his belt. "You," he said to Stanley, who was standing round-eyed. "Come join the party, old Albert, old bean."

Stanley obligingly shuffled forward. McNabb handcuffed the right hand of Burrows to the left hand of Stanley. "There's your package, all wrapped up for you, Mr. O'Keefe," McNabb said. "Make them comfortable."

O'Keefe herded them into the backseat of the car and got in with them, and now McNabb turned smilingly on Solo.

"Going swimming, Mr. Solo?"

"This is the day for it, Mr. McNabb."

"What's with all the nudity? What's with swim trunks?"

"Burrows thought it safer—for them—if he stripped me down."

"Got to hand it to him. He's a wise old campaigner."

"Now what's this all about, Mr. McNabb?"

McNabb drew out a handkerchief, wiped his face. "Hot day, hey?"

"Yes, it's a hot day. What's this all about, McNabb?"

"Defection. A young girl. Pamela Hunter. You were in for the works. They were going to give you the cyanide business in a locked room—you, Illya, and the ambassador's kid. Too rough on a young girl, a new recruit. Couldn't take it. They laid it on too stiff on their new recruit; they weren't prepared for a failure by the vaunted Stanley. Couldn't take it. Basically a nice girl roped in by their phony speeches; you know how their phony speeches can brainwash a youngster till the youngster's roped in and tied up and a criminal by reason of crimes already committed. This little girl wised up in time, thank heaven. It got through to her—what they are, what they were making of her. Defected. Brought out Illya and young Winfield. We're in the clear, and we've got Stanley back. Let's go."

"Why the cyanide treatment? I don't get it. We were going along. We were giving them back their ace saboteur."

"THRUSH," McNabb said. "A basic rule of THRUSH. Kill the witnesses."

"Who witnessed? What witnesses? What?"

"Illya saw Stanley, Hunter, Burrows—could identify them. Young Winfield saw Hunter and Burrows—could identify them. You saw Stanley and Burrows—could identify them. A matter of recognition. THRUSH does not like recognition; the fewer that can recognize, the better they like it. Whoever can recognize is a witness—if not for the present, for the future. In their scheme of things the best witness is no witness—and a dead witness is no witness. Therefore the cyanide treatment. Let's go, young fella."

"No." Solo's voice was sharp.

For the first time McNabb showed concern. "What's up?"

"Inside there. Tudor."

"Forget it. You win a major battle; doesn't mean you have to win the whole war. There are reinforcements coming up and a new plan of attack, with the Old Man in charge. We've won our battle; we have Stanley back, and we have Burrows, and even the girl."

"But inside there—Number One. Tudor!"