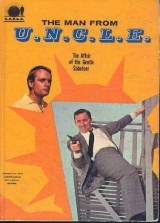

Текст книги "[Whitman] - The Affair of the Gentle Saboteur "

Автор книги: Brandon Keith

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 6 страниц)

8. The Living Beacon

AT UNCLE headquarters Mr. Solo was being prepared, but with caution.

"Remember that," Waverly said. "Caution! You're young; I've known you to be foolhardy, to go to daring extremes. Don't!" They were in the Laboratory Room. Solo was being fitted out with his equipment, and they were waiting for what one of the lab technicians had called "your galvanized thick shake."

"Caution." Solo grinned. "Yes, sir."

"There are lives at stake, Mr. Solo—an innocent boy, your friend Kuryakin—so please, no heroics. Your job is to deliver Stanley and effect the return of our two. It sounds simple; it may not be as simple as it sounds. If it works out simply, well and good—don't push it. If not"—he shrugged—"we're arranging precautions. But essentially your job is to effect the exchange."

"Right," Solo said. "Anything else?"

The Old Man rubbed a finger along his jowls and his smile was small. "Well, if without risk–without any risk, mind you—if by chance—you'll be in the field, you know—if by chance and without risk you can find out anything about Leslie Tudor, we would, of course, appreciate that."

"Ready," a white-jacketed technician called. "Here you are, Mr. Solo." He brought a tall glass filled with a thick cream-colored mixture.

Solo made a face. "What's it taste like?"

"Good, as a matter of fact. We flavored it with vanilla syrup."

"Well, here goes." Solo gulped it down, grimacing.

"That bad?" the technician said, but his expression had gone sour in sympathy with Solo.

"Let's put it this way," Solo said. "If I sponsored it to replace malted milks, I'd go broke."

The technician laughed. "Well, it's down and that's what counts. You're ionized. From here on out you're a living beacon, electronically charged. For the next twenty-four hours you'll have these ions in your bloodstream. Harmless, but most effective. Listen." The technician went to a wall and touched the switch of an instrument. A sharp, penetrating screech filled the room.

Waverly put his hands to his ears. "Enough." The technician switched off the sound. "They'll be able to hear that, in the cars, within a hundred mile radius."

"What cars?" Solo asked.

"We'll go to my office now," Waverly said.

In the office, he sat behind his desk and lit his pipe. "The car's waiting upstairs. Nothing special, an ordinary Chevy. They'll bring Stanley out to you, and off you'll go. You'll follow Burrows' directions to the letter."

"How much does Stanley know?"

"That they have hostages, and he's being exchanged for them."

"Does he know who?"

"No."

"May I tell him?"

"For what purpose?"

"To prevent him from trying to make a break. If he knows who, he'll know how stupid he'd be to try to break."

"He's not quite the type, but yes, you may tell him; no reason why not."

"And if he does try to break?"

"Then you'll have to use your pistol, but low, not for a kill. You'll get him back to the car and proceed according to instructions. A wounded Stanley would be infinitely better than a dead one. Our object is rescue, not retribution. By the way, do you have your sunglasses? It's blistering out there."

"I have them."

Waverly opened a drawer of his desk, took out a pair of sunglasses, and handed them up to Solo. "For Stanley. To keep him comfortable. What's good for you is good for him. As long as we're doing what we're doing, we may as well do it properly right down the line. Now about those cars."

"Yes?" Solo said.

"There'll be five cars, ten agents, two in each car. They'll be all around you, at various distances, out of sight, of course. But they'll be able to judge just where you are by instruments, marking you by the electronic sound that emanates from you."

"Be careful," Solo said. "No interference. We really don't know how many of them there are; perhaps Stanley himself doesn't know. You said yourself there are lives at stake. That poor kid, and Illya..."

"A most careful man is in charge. McNabb."

"Excellent."

Waverly looked at his watch, then stood up. "You have all your equipment?"

"Everything."

"Good luck, Mr. Solo."

9. "A Crazy World"

SOLO DROVE. Stanley sat silently beside him. It was early, the city traffic was not heavy, and they crossed 59th Street bridge without misadventure. There, as Solo made the turn into a narrow one-way street leading toward the highway, he saw the car bearing down on him, going the wrong way on the one-way street. He jammed on his brake, veered, as did the other car; their collision was light, but their bumpers were firmly entangled.

Solo got out, wary, ready for a trick from THRUSH, but from the other car there emerged a squat, elderly woman, fat and perspiring and obviously frightened.

"Gee whiz, mister, my fault," she said, "my fault entirely."

"Yes, ma'am," Solo said, keeping an eye on Stanley.

"I got onto this one-way street just by the other corner. Like before I knew it, I was on this one-way street. Figured I'd go the one block and get off and then, boom, there you were."

"Yes, there I was, wasn't I?" Solo smiled. This was no trick of THRUSH.

"Gee whiz, I sure hope there's no damage, mister."

"Doesn't seem to be. I'll just have to pry us apart."

"I mean, I hope you won't sue me. I'll pay you right here for any damage. I've got some cash on me; if it's not enough, I'll write you a check. You can have my name and address from my license. Anything you say. The thing is—my husband."

"Your husband?" Solo inquired.

"He always ribs me that I'm a lousy driver. Maybe I am, but you don't like it your husband always ribbing you you're a lousy driver. When I get a ticket, I don't care; I pay it and my husband, he don't know about it. But if I get sued, a lawsuit, he has to know—because the car is in his name. You know?"

"Sure," Solo said. "Don't worry, ma'am. There's hardly any damage at all, as you can see. No damage, no payment, no lawsuit. And now if I can get us unhooked—"

"You are a gentleman and a scholar." The fat lady smiled with big white teeth. "And also very handsome, if I may say."

"Thank you, ma'am."

He went to the locked cars, the woman toddling with him. Her bumper was over his, and her car was heavy. He pulled at the bumpers to no avail; he could not dislodge them. Perhaps he should ask Stanley for help. No, better to keep him sitting where he was. He tried again, knowing the strength of one man was not enough; he would have to use the jack from the rear compartment of his car. Then he heard the woman whispering behind him: "Oh, no! We got company. Just my luck."

He looked up. A police patrol car was rolling to a stop behind his car. One of the policemen got out and strolled toward them slowly. He was heavy-set and red-faced, gray hair showing beneath the sides of his visored cap.

"Well, what have we got here?" he said in a gravelly voice.

"Bumpers caught," Solo said. "Would you give me a hand, please, Officer?"

The policeman disregarded him. He looked from one car to the other, then pointed to the one obviously at fault.

"Who owns this heap?"

"Me," the lady said.

"What are you doing wrong way on a one– way?"

"I made a mistake," she said lamely.

The policeman puffed up his cheeks, blowing out a sigh. "Just a little mistake, hey? You got a driver's license, by any chance?"

"Sure."

"Okay, let's have it."

She took her handbag from her car, and from the handbag produced her license. The police man read it slowly.

"You Rebecca Brisbane?"

"Yes, sir."

"Do you own this heap?"

"No, sir. My husband."

"Where's the registration?"

"Right here, sir."

She gave him the certificate of registration. He studied it carefully, compared it with the license plate of her car, sighed again, took out his book, and laboriously wrote out the summons. Solo wanted to hurry him but didn't dare. This policeman, positively, wasn't in a pleasant mood, or, simply, he wasn't a pleasant man.

"Okay, Rebecca," the policeman said. "Wrong way on a one-way, that's a violation. You could have killed this gentleman. You know?"

"Oh, I know. This is one ticket I deserve."

For the first time the policeman smiled. He gave her the ticket, the driver's license, and the certificate of registration, and Rebecca returned her possessions to her handbag. Solo fidgeted in the morning sunshine, watching Stanley. Stanley sat uncurious, immobile, disregarding them.

"Now you get back in your car, Rebecca," the policeman said, "and we'll get you loosened up." He put away his summons book and his pen. "You and me ought to be able to manage it, young fella."

They went together to the entangled bumpers. Solo opened his jacket. They wedged their hands beneath the bumper of Rebecca's car. "When I say heave, we'll heave," the policeman said. "One—two—three—heave!" The bumpers became disengaged. "Okay," the policeman called to Rebecca. "Put her in reverse and back up—slow."

Rebecca obeyed. Grindingly her car moved away from Solo's.

"Okay, keep going like that," the policeman called. "Back up to the corner and go your way."

Solo watched until the car disappeared around the corner, turned to thank the policeman—and found himself facing a leveled gun!

"What in the world—"

"Easy does it, young fella. Into the prowl car. Move."

"But—"

"You heard me! In the prowl car. Now move!" The man in the passenger seat of the police patrol car was a sergeant with a gold badge. Rigidly, observing intently, he watched as Solo, under the policeman's direction, entered the car from the driver's side. Then the policeman got in, slammed the door, and Solo was wedged between them, the muzzle of the policeman's gun a sharp warning thrust into his ribs. Solo could see Stanley in the car in front. Stanley was sitting motionless. If this were some complicated deception engineered by THRUSH, then by now Stanley should be out and running. Or was it a deathtrap? He was helpless, wedged between them, the muzzle of the gun tight in his side.

"What's up?" the sergeant said.

"This baby's got a gun on him, that's what's up. He had his jacket open when we were working on them cars. He's wearing a shoulder holster."

"Yes?" the sergeant said.

Solo breathed deep in relief. No deathtrap. Proper police work. But now it became a matter of time. Enough time had been wasted. He had an important appointment, but he was not at liberty to divulge it. "Yes," he said.

The sergeant slipped a hand beneath Solo's jacket, opened the holster, and drew out the pistol.

"You got a permit for this firearm, mister?"

"Yes, but not with me."

Aside from his driver's license there was very little in the way of identification he did have with him. On this kind of job, the fewer papers that could fall into the hands of THRUSH the better.

"Why not with you?" the sergeant said.

"It's hard to explain."

"Well, try."

"I'm on official business. That man up there in my car is a prisoner. I'd appreciate it if you kept an eye on him."

"We're keeping an eye on him," the policeman on Solo's left said. "Just let him make a move and you'll see. But we are also keeping an eye on you, buster."

The sergeant asked, "Any proof of this official business?"

"I'm sorry; no."

"What's your name?"

"Solo. Napoleon Solo."

"What kind of official business?"

"I'm sorry, but I can't tell you."

"By any chance, if I may ask—you got a driver's license, Mr. Solo?"

There were two guns on him now: the police man's, and his own in the sergeant's hand. He moved gingerly getting out his driver's license. The sergeant inspected it and returned it.

"I'm afraid we're going to have to take you in, Mr. Solo. You and that guy up there—your prisoner, you say."

"No," Solo said.

The sergeant had a calm, level voice. "Could be you're telling the truth; these are crazy times we're living in. In that case, can you blame me? You're a guy with a gun and no permit. You say you're some kind of law enforcement officer on business. Could be. But you got no proof for us. So we got to take you in, don't we? At least until that proof is furnished?"

"Yes," Solo said. "But no."

"You're losing me, mister." Exasperation put a flush on the sergeant's face. "Yes—but no. What kind of an answer is that?"

Solo sighed. "Yes—because you're right. Certainly, logically, of course you'd have to take me in. No—because it's a matter of time. I'm on an urgent mission and time is of the essence."

"Then what do you want, mister? That we take your word for it? What would you do in my place? Take your word?"

Solo snapped his fingers, pointed at the two– way radio.

"Who's your man in charge, Sergeant?"

"Lieutenant Weinberg."

"Can you get through to him?"

"Sure."

"Would you do that, please? Tell him to call this number." Solo spoke Alexander Waverly's private number. "Tell him to ask for Waverly."

Perplexed, the sergeant said, "Who's Waverly?"

"Please do as I say, Sergeant. Believe me, this is urgent business and official business, and if you don't cooperate you'll be subject to censure. You've nothing to lose, sir. If it doesn't work out then you can take me in, and I'll have no cause for complaint."

The sergeant shifted about uncomfortably.

Solo understood his dilemma. If the sergeant com plied and then the man with a gun without a permit turned out to be some sort of crank, the sergeant would be labeled a fool by his colleagues. If he did not comply and then the man truly turned out to be an agent on urgent business, then he would be severely reprimanded by his superiors as an inflexible fool.

And now the policeman on his left said sarcastically, "That prisoner you say you got up there– he don't seem to be in no hurry to try for an escape, does he?"

Solo made no reply to that. He looked to his right.

"Please, Sergeant," he said. "Time. Don't let me run out of time."

The sergeant touched a switch. The short wave thrummed, crackling. "Lomax here," the sergeant said. "Harry Lomax. Put me on with the lieutenant."

"Okay, Sergeant," the voice answered.

"Lieutenant Weinberg here. What've you got for me, Harry?"

"I got a crazy one, Lieutenant. I got a guy with a gun, no permit. Says he's some kind of law enforcement officer but he's got no papers to prove it. Wants you to call this number." He stated the number. "You're to talk to a Mr. Waverly. This guy here says this Waverly will straighten you out. His name is Solo, Napoleon Solo."

"Hold it a minute," Solo said.

"Just a minute, Lieutenant." He turned to Solo. "What?"

"Insurance," Solo said. "Let him tell Waverly that you people picked me up because of a minor traffic accident. And let him just state these additional names—Kuryakin, Winfield, Stanley, Burrows. That should do it."

Into the microphone the sergeant said, "Do you hear that, Lieutenant?"

"You sure you're all right?" the lieutenant's voice crackled back.

"If I think I'm getting you right, Lieutenant– yours truly's sober as a judge."

Brief laughter came through clearly. "All right, Harry. Stay with it. I'll get back to you."

Silence.

They sat, Solo between the two pistols pointed at him.

Then, finally, the radio came alive. "Harry! Sergeant Lomax! Weinberg here!"

"All yours, Lieutenant."

"A-okay on Napoleon Solo. Let him loose and forget the whole deal."

"You sure, Lieutenant?"

"Let him loose. That's an order."

"I got his gun."

"Give it back to him."

"Okay, if you say so."

"I say so. And wish him good luck from me." The radio went dead. The sergeant returned Solo's gun and Solo buttoned it into the holster.

"Sure is a crazy world today," the sergeant said. "Good luck from the lieutenant. Lieutenant Weinberg tells me to tell you good luck from him."

"Thank the lieutenant for me," Solo said. "And thank you, gentlemen."

"Don't mention it," the sergeant mumbled and opened the door and got out. Solo followed and the sergeant watched, his brow crinkled, as Solo got into his car and drove off.

"Local police—efficient officers," Solo said to Stanley. "They mistook me for somebody else, but they didn't jump all over me; stayed patient and proper till we got ourselves straightened out." He glanced at his watch. "We're still okay for time. It's a good thing we started early."

Stanley said nothing.

10. Rendezvous

IT WAS A scorching morning, without wind, humid and hot, the sun blazing through the windshield directly at them. Solo put on his sunglasses, gave the other pair to Stanley, who accepted them with out spoken comment but with a grateful grunt. They were a half-hour out now, not speeding but going at a good pace, and already on the highway. In that time Stanley had not said a single word.

He was clean, spruce, shaven, and smelled of pomade. Solo wished he would say something.

"Have you been treated well, Mr. Stanley?"

"I have no complaints."

Solo, watching the road, made a proper turn, then settled back.

"Do you know where you're going, Mr. Stanley?"

"I'm being returned to my people."

"Do you know why?"

"My people have acquired hostages, and I'm being exchanged for them."

"Do you know who?"

"No."

"Would you like to know?"

"I don't care. It's sufficient that I'm here alone with you, driving along your remarkable highways. Whoever the hostages are, they must be important. My people aren't idiots. Nor are your people, for that matter."

Solo shook his head. "Pretty cool, aren't you?"

"Cool? Contrary. Hot. Is it always so beastly hot in your country?"

"Not in the winter."

That brought a chuckle from Stanley and a sidelong glance.

"How long before we get to where we're going?" he asked.

"One o'clock, the man said."

"What man?"

"Burrows, I think."

"Probably."

"Talked to me on the phone, made the arrangements. Of course, it might have been Tudor."

"I wouldn't know," Stanley said. "All right, whom are they holding?"

"The man who worked with me when we picked you up. Also, the son of the British Ambassador to the UN."

"Two for one. I'm important, eh?"

"Seems you are."

Stanley lit a cigarette, threw the burnt match out the window.

"It pleases the ego."

"Pardon?" Solo said.

"When one knows that one is considered important."

"Important to them, perhaps, Mr. Stanley; not to us. What we think of you would not, I assure you, please your ego. You mean nothing to us. Should it enter your mind, for instance, when it happens we're stopped for a light, to bolt, I'd shoot you down like an animal."

"Sorry, but I won't afford you that pleasure. Run? Where would I run? A fugitive in a strange country? I'm not quite the type. I imagine you would know that by now. Albert Stanley is a thorough professional who prides himself in his work, but he's never, ever, pretended to be a blooming hero."

"Just wanted to clear the air."

"Nothing to clear."

"So be it."

Solo drove. The little man slumped down, leaned his head back, closed his eyes, and appeared to be asleep—but he was not. Each time the car stopped for a light his eyes opened. But as they went farther east, the lights grew fewer. There was less and less traffic, and it was hot. The sun was high now, burning down, and the car was like a cauldron. Solo opened his collar and pulled down his tie. He used a handkerchief on his face and down his neck. His body was wet with perspiration. Finally they came to Savoy Lane, broad at this section, and Solo pulled the car to a side. It was ten minutes to one. He took a road map from the glove compartment and opened it on his knees. The little man sat up and leaned over.

"May I be of assistance?"

"Remington Road. You know where it is?"

"No, I'm afraid I don't."

Solo pointed it out on the map. "That's where we're going. Not far now." He put away the map and started up the car. Savoy Lane grew narrow, finally leading them to Remington Road, and Solo understood why this was the appointed area. It was a flat, relatively uninhabited region. If Burrows was observing them through field glasses he could see for miles, and he could see whether they were part of a convoy, whether cars were following them. Solo made the turn onto Remington Road, drove north a few hundred yards, pulled up the car on the shoulder of the road, and turned off the ignition. "Okay," he said. "Out."

"Where are we going?"

"I don't know. We're following instructions." They walked north. It was a dirty, dusty country road, no houses in view, nothing but the high blue sky and the blazing sun. Solo turned once; he could no longer see the Chevy. No car passed them in either direction. The road was desolate, deserted, unused. Their shoes kicked up dry clouds of dust as they trudged, and finally the neat little man was no longer neat. His hair glistened wetly; rivulets of perspiration coursed down his cheeks; his suit was crumpled in damp wrinkles; his shirt collar was a sodden circle around his neck. He took the kerchief from his breast pocket, flapped it open, and mopped his face.

"How long?" he said.

"Our orders are to walk."

The little man grinned slyly. "He certainly picked an excellent location for the rendezvous, didn't he?" He stopped and looked about. "Nothing can be following us, no car, no man, nothing."

"Nothing," Solo said, knowing there were cars about, somewhere, far perhaps, but somewhere, their special instruments attuned to whatever it was he was carrying in his bloodstream. What was it the lab technician had called him? A living beacon! "Yes, nothing," Solo said.

"Leave it to Burrows. I can't say I'm enjoying this, but I must say I admire him."

Again Solo fished for information. "Burrows or Tudor?"

"I don't know, but whoever," Stanley said.

They trudged, kicking up dust, the sun burning overhead. Then, at long last, a half-hour by Solo's watch, they heard the sound of the motor behind them, the first sound of a car in all their long walk, and they stopped. A long, sleek, gray Rolls Royce purred slowly past them, braked a few feet in front of them, and they came to it. The driver was hatless, a dark man in an open-necked sport shirt.

"Stanley," he said.

"Hello," Stanley said.

"Thanks for nothing," the dark man said.

"You can't always win," Stanley said.

"What went wrong?" The dark man's voice was flat.

Stanley shrugged. "I don't know. Ask him."

"What went wrong, Mr. Solo?"

"UNCLE has eyes," Solo said.

"Where?"

"Everywhere. He was recognized."

"Where?"

"This time at the airport. When he arrived. Next time—who knows?"

"Recognized," the dark man snarled. "All right. Get in. Both of you."

They sat in the rear. Stanley lit a cigarette.

The Rolls glided forward, picked up speed.

Just like that, Solo thought. He knows I've got a gun, yet he sits up front with his back to me. It is a contempt, and he's enjoying his contempt of me. He knows I won't make a move, I can't, and he's enjoying making me sweat. He has Illya; he has a seventeen-year-old boy, so he is perfectly confident and enjoying it and rubbing it in. He is unhappy about Stanley's failure, but he is happy about the method of Stanley's return. Power gives confidence: He has Illya and the boy and now he is getting Stanley, and UNCLE cannot retaliate. It is a superlative contempt. Through me, rubbing my nose in the dirt, he is rubbing UNCLE's nose in the dirt.

The Rolls purred through Remington Road, grown marshy now, high weeds on either side, no houses, utterly desolate, and then the Rolls veered off the road and stopped in the weeds.

Burrows turned his head. "You. Solo. Get out." Solo opened the rear door, Burrows, the front door. They came out of the car together. Burrows was tall, with long arms and powerful hands.

"This way." Again the contempt. He walked ahead, into the weeds, his back to Solo. He had a strong tread, catlike. He walked without swinging his arms, and in his right hand he held, of all things, a pair of black swim trunks. He pushed through the tall weeds, Solo following, until they came to a small, round clearing surrounded by the tall weeds. Now Burrows turned, smiling.

"I imagine you're armed."

"You've a good imagination."

"And I imagine you're equipped with some weird little hidden gadgets—like a pistol disguised as a fountain pen, or a button of your jacket that's really an explosive capsule. Well, we're going to get rid of all of that."

"Are we?"

"Take your clothes off. Everything."

"Everything?" Solo said modestly.

"Everything!"

"And what do I do with the clothes after I take them off?"

"You leave them here, right here. Now come on! Start!"

Solo took off his jacket and dropped it to the ground, and his shoulder holster, and all the rest, including his shoes and socks. Then Burrows tossed him the swim trunks and he climbed into them.

"All right. You in front of me this time. Move!" Solo understood. Burrows was not turning his back now, not giving him any opportunity to pick up some tiny harmless object that could in fact be a weapon. In sunglasses and swim trunks and nothing else Solo walked gingerly, barefoot through the prickly weeds, back to the car.

"Going for a swim?" Stanley said.

"This is the day for it," Solo said.

Burrows, in the front seat, slammed the door, backed the car out from the weeds and straightened it on the road. He opened a compartment in the dashboard and drew out a microphone. He held it close to his lips and spoke softly. "All in order. We're coming in. Be there in thirty minutes."