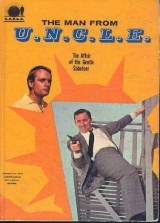

Текст книги "[Whitman] - The Affair of the Gentle Saboteur "

Автор книги: Brandon Keith

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 6 страниц)

5. "No Way Out"

THEY WERE NOT uncomfortable, although they had no idea where they were or when it was day or night. It was a large, windowless room fitted with a prison-type steel door. They could hear no sounds from outside. Illya believed it to be a basement room because of the feeling of dampness and because, by tapping and testing, he had found the walls to be of concrete, even the ceiling. He had stood on Steve's shoulders and rapped his knuckles at the ceiling.

"All concrete." And he had leaped off. "A concrete room."

"What are those up there, Mr. Kuryakin?" Steve pointed to the holes.

There were four of them, two-inch holes, one in each corner of the ceiling.

"For ventilation. So we can breathe."

"You mean if they turned it off—the ventilation, I mean—we would—well—like choke to death?"

"Now why would they want to do anything like that?" Illya laughed. He was doing a lot of laughing, with a lot of effort, but the least he could do was try to keep up the boy's spirits. "You heard me when I talked to Mr. Solo." That of itself troubled Illya. Why had they permitted the boy to be present? Over the micro-TV, under instruction, he had mentioned both THRUSH and Albert Stanley. They would not permit information like that to leak to a youngster unless—unless…

"We're to be exchanged," Illya said, "just as you heard, for Albert Stanley. How do you like being a hostage?"

"I think I like it." Steve grinned. "I mean– hostage. Now that's something to tell my grandchildren about."

"Grandchildren yet! A bit premature, aren't we, Stevie boy?"

"Figure of speech, sir."

"Of course." He slapped the boy's shoulder, chuckling.

The tall, dark man had held a gun to him, and he had said what he had been told to say over the micro-TV; then it had been taken away from him. They had been ordered to undress and supplied with new clothes, underwear, baggy slacks, sport shirts, and crew socks, and that had been the last they had seen of the tall, dark man. Their food was served through a slot in the prison-type door by the blond girl. They were not uncomfortable.

"THRUSH," the boy said. "I've heard about them from my father."

"And there've been fathers who've heard about them from their sons."

"THRUSH," Steve said. "The bad guys."

"That about sums it up, lad. Depends, of course, on the viewpoint. For them they're good; for us, bad."

"Who is Albert Stanley, Mr. Kuryakin?"

"One of the bad guys—from our viewpoint. Our side caught up with him—and their side caught up with us. Fair, or unfair—again depends on the viewpoint—fair exchange, and you and I'll be out of here."

"I can't believe it."

Startled, Illya shook that off and said quite blithely, "Well, aren't you the pessimist!"

"Me? I?"

"Can't believe we'll be out..."

"Oh, no, not that. I mean, Miss Hunter. She's so lovely."

"You've got a pretty sharp eye right early, young fella."

"I can't believe—I mean, Miss Hunter, a bad guy. I wish she weren't."

"Stevie boy, so do I. But emphatically!"

And they both laughed.

They were not uncomfortable. They had electric lighting, books and magazines; there were beds, tables, chairs, and toilet facilities. And there was, of all things, a pool table, fully equipped: balls, cues, rack, chalk, and all. That delighted Steve, who was an excellent pool player, but depressed Illya. The plastic balls and the wooden cues could be weapons. Would THRUSH provide weapons unless THRUSH full well knew there would never be an opportunity to use them? Illya said nothing of that but played pool with Steve Winfield. They spent hours at the table with Illya consistently being beaten until they arrived at a handicap figure. Illya was given twenty-five points in advance in a hundred-point game; that made it a contest and the hours sped by in intense competition. Now, at the end of a game, Illya being defeated by a single point, Steve laid his cue on the table.

"What time do you think it is, Mr. Kuryakin?"

"Not the faintest idea—but night, I'd say. I mean like I'm beginning to feel a bit sleepy– else I wouldn't have missed that shot I did miss."

"Me, I'm beginning to get hungry."

"She hasn't failed us yet, has she?"

As though in corroboration, the slide-panel in the door scraped open.

Illya squatted and peered through. The blond girl was wearing gold slacks and a gold blouse.

"You're very beautiful," Illya said.

"Please don't," she said.

"Actually I'm conveying the compliments of young Mr. Winfield. Mine, too."

"Thank him for me." She smiled.

"She thanks you," Illya said over his shoulder, and then his vision was blotted out by plates passing through. There were two tongue sandwiches and two Swiss cheese sandwiches and two glasses of milk. It was probably night, a snack before sleep. The meal before had been roast beef hot with gravy, peas, potatoes, bread and butter, and coffee.

"What time is it?" Illya asked.

"I'm not supposed to talk to you," the girl said.

"How go the negotiations?"

"I don't know."

"When are they going to let us out of here?"

"I don't know."

"Where are we?"

"I can't talk to you anymore. Good night."

So it was night. Without realizing, she had given some information. She was becoming accustomed to talking with him. Each time that she opened the slide-panel he made conversation, each time trapping her in some minor admission. So, he hoped, he might learn more. For what? What good would it do? What good if he drew a major piece of information from her? They were locked in, penned, like animals. Information could satisfy curiosity, what else? Any time their captors pleased they could turn off the ventilation—and it would be a long, horrible death.

There was no way out, no means of escape. He had thought out every possibility: There was none. He could hurt the girl; if he wanted to, he could kill her. He could be ready for her with the back of the pool cue. When she opened the slide-panel he could shoot it through, with power, at her head. He could knock her unconscious, he could kill her, depending upon the amount of force he used. But to what purpose? None, except vengeance. What vengeance upon all of THRUSH to harm a young girl even if she was one of them?

He turned to the boy now seated at the table, eating, sipping milk.

"Delicious," Steve said. "We can't complain about the food in this hotel, can we?"

"That we can't."

"Aren't you hungry, Mr. Kuryakin?"

"I am."

"Well?"

They ate. Steve washed the dishes. They played another game of pool, then went to sleep.

6. "Two Trumps"

ON THAT SAME day the men in the room at the Waldorf-Astoria had been recalled—that work was done—and, still later, Alexander Waverly himself called on Sir William Winfield and informed him of the circumstances.

"There must be no outcry, Sir William. No public mention. The boy's safety depends on absolute secrecy."

The ambassador was tall, spare, white-haired. "What do you think, Mr. Waverly? Please don't try to be kind to me. I want it straightforward. Your honest opinion, Mr. Waverly."

"They'd be crazy to harm him."

"THRUSH has done crazy things in its time."

"But what sense this time? They want Albert Stanley, and we'll give them Stanley because we want your boy and our Mr. Kuryakin. Oh, we're going to be right on top of it all the way, that I can assure you. I don't trust them, of course not. They play tricks, we know. But what purpose any trick this time? Their object is the return of Stanley. Essentially this is an exchange—we have what they want and they have what we want. But we must not upset the applecart, Mr. Ambassador. There must be no public knowledge of the kidnapping of young Steven."

"I understand."

"I know how you must feel about this, and you have my deepest sympathy. But please do remember, sir, we ourselves are not unskillful in matters like this and all our resources shall be concentrated."

"May I work with you?"

"I beg your pardon, Sir William?"

"I just can't sit around here, waiting. May I be with you? Perhaps I can be of some small service. Perhaps they'll want to talk directly to me—about my son. Whatever. You must understand. May I join...?"

"Of course."

And so Sir William Winfield was present during the turmoil of preparation in Solo's apartment early the next day. Portable equipment had been brought in, and there were many special agents of UNCLE; there were also Solo, Waverly, and McNabb. Albert Stanley had said there were but three others of THRUSH here in the United States on this job—Leslie Tudor, Eric Burrows, and Pamela Hunter. Tudor had a "passion for anonymity." Hunter was a young person being indoctrinated by the "bigwigs." So—if Stanley had told the truth—it would be Burrows who would make the contact. Solo, like Illya, had heard about Eric Burrows but did not know him, had never before seen him or talked with him. But McNabb had, and so McNabb was present, a headset over his ears.

Activity thrummed in the early morning in Solo's apartment.

Telephone wires were spliced and attached to tape recorders and electronic gear. Contacts were made with agents previously assigned to the central office of the telephone company in New York and Long Island. Tests were run, jokes were made, but the overall atmosphere was deadly serious. And now all was in order; the specialists, wearing their headsets, sat silently at their apparatus, waiting impatiently. Waverly sat in a corner, smoking his pipe. Sir William Winfield sat nearby, his hands clasped in his lap. There was no sound in the room except the sound of Solo's pacing.

Promptly at nine o'clock the phone shrilled. Solo lifted the receiver. "Hello?"

"Mr. Solo?"

"This is he."

"First this, Mr. Solo. Any attempt to trace this call will be perfectly fruitless. We're not amateurs, as, I might imagine, you're aware. Many and varied electronic cutoffs have been installed. So don't try to draw out this conversation in any hope that you'll trace me. I'm free to talk with you as long as you please—but to the point. Have I made myself clear?"

"You have. With whom am I speaking?"

"That, Mr. Solo, is not to the point. Who I am is no concern of yours. Or who you are, for that matter. What does matter is Albert Stanley. Do you have him ready for us?"

"We do."

Waverly was standing over McNabb. McNabb looked up and nodded. "It's Eric Burrows."

"These shall be your directions, Mr. Solo," Burrows said. "If you wish to get a pencil to write them down"—short laugh—"be my guest."

"I'll do that. Hold the wire." He did not need a pencil. The recorders would take down the directions. But he put down the receiver with a bump so that the person at the other end of the wire could hear, and he went to the specialists with the headsets.

"Nothing," he was told. "His cutoffs are working. We're getting plugged into personal conversations, business conversations, and busy signals. He's done a beautiful jam-up. We're useless."

"It's Eric Burrows," Waverly told him.

Solo picked up the receiver. "Hello? Okay. I've got pencil and paper."

"Listen closely, please. You, alone with Stanley, will drive out to Long Island in the Southampton area. But alone, Mr. Solo!"

"Naturally."

"If you try tricks, you'll get tricks. Remember about your friend Kuryakin and the boy from England."

"I am remembering."

"You can anticipate a three-hour drive."

"Yes."

"You—together with Stanley—will drive out to the intersection of Savoy Lane and Remington Road on the North Shore. You will find it a rather untraveled, desolate area, Mr. Solo, which is in accordance with the general idea, if you know what I mean."

"I believe I know what you mean."

"I believe you do. You will be there, at that intersection, at one o'clock this afternoon."

"One o'clock," Solo repeated.

"Remington Road runs north and south. You will drive a couple of hundred yards north on Remington Road and then you and Stanley will abandon the car. You will drive it up on a shoulder of the road and leave it there. Am I coming through?"

"Perfectly."

"Then you and Stanley will walk north. In time you will be picked up."

"What time?"

"Any time of our choosing. You will walk north. Clear?"

"Yes."

"Remember about the boy and Mr. Kuryakin."

"I'm remembering."

"If you put any value on their lives, remember to keep remembering."

"I'll remember to keep remembering. Anything else."

"That's it."

"Now may I ask a question?"

"Certainly."

"What about Kuryakin and young Winfield?"

"They're being cared for."

"I assume they are. I mean, how does it work out—the exchange?"

"A fair question. Certainly. Once we have you and Stanley, we will take you to Kuryakin and the boy, and we'll lock you up with them."

"Lock me up?"

"A proviso against any foolish antics by UNCLE. As you know, we've failed to accomplish our mission. Retreat, when necessary, is an honorable tactic of war. All we want is Stanley and an opportunity to get out of your country. Are we asking too much—seeing as we hold hostages?"

"I don't know. Depending..."

"You'll be confined, together with Kuryakin and the boy, for one hour. But only for an hour. That will be sufficient time for our group to be safely out of your country. We shall then be in radio communication with the American authorities, and you three will be released. A precaution, but the kind of precaution you yourself would take, would you not?"

"I suppose..."

"That's it, Mr. Solo. Any more questions?"

"No more questions."

"Don't try tricks, I beseech you. We'll be watching, and we can meet your tricks with tricks of our own, but in this particular game, this time, we hold the trumps. Two trumps. Illya Kuryakin and Steven Winfield. No trick can be successful. If you win, you lose, because what you will win will be two corpses. Do you read me, Mr. Solo?"

"I read you clear."

"Good-bye. See you later."

7. Game Without Rules

ERIC BURROWS cradled the receiver and smiled toward Pamela Hunter. "There! Did I omit any thing?"

"Nothing. You were precise and specific."

"Well, thank you, my dear."

"Now if he'll only comply—no tricks, no complications—then all of this will be over with and finished."

"He has to comply. No alternative."

"I'll be happy when it's over."

"Are you frightened, Miss Hunter?"

She shook her head. "No, it's not that. Just—I don't like it—any of it."

"Who are you to like—or not like?" Burrows' eyes narrowed.

"I'm nobody."

"If you'll just keep repeating that to yourself, over and over, you'll have mastered the first lesson. That's who and what you are exactly—nobody. You're a tiny unimportant cog in a vast machinery. You have nothing to do with decisions. You are part of the machine that grinds out the work and, may I add, a dispensable part. What I mean is, if we lost you, it would be no loss to the machine. You'd be replaced cheaply and quickly. The Americans have a phrase for it—you're a dime a dozen, my dear."

"Not very flattering."

"The truth rarely is." His dark eyebrows contracted. "I'm curious. You don't—didn't—like any of it. You're pleased by our failure. Why?"

She went near a window of the large drawing room and looked out. The window was closed, the room air-conditioned. Outside, even so early in the morning, it looked hot. The sky was clear. The sun gleamed on the long lawns. "Because," she said, "to destroy shrines, to kill people..."

"But it had a purpose."

"I know. But innocent people..."

"Incidental. The shrines were the purpose—the effect of the destruction of the shrines." He laughed briefly. "Any killings would have been incidental. We failed. Now we must kill—not incidentally. By the way, has Leslie had breakfast?"

"Yes."

"Is there still coffee?"

"Yes."

"Would you bring me a cup, please?"

"Certainly, Mr. Burrows."

In the kitchen she poured hot coffee into a mug and set it on a tray. She added a small pitcher of cream, a spoon, a container of sugar, and a napkin and carried the tray into the drawing room. She was troubled, hesitating to open the subject again, watching as he stirred cream and sugar in the cup. He sipped, then lit a cigarette. He sat at a table drinking the coffee, smoking. She remained standing.

"I don't quite understand, Mr. Burrows."

"What?" he said pleasantly, exhaling a cone of smoke.

"What you said before."

"Said before?"

"Now we must kill—not incidentally."

The dark eyes looked up at her. She felt dizzy, weak, pulled as though drowning in a sea of dark eyes. "You've a right to be informed, Miss Hunter. After all, all of us are cogs in the machinery. There must now be killings with a purpose. The boy, Kuryakin, and Solo."

"Oh, no!"

"Yes."

"But why? What possible purpose?"

The dark eyes remained fixed on her. "Stanley will be delivered, and Solo taken. You heard me on the telephone. Solo will be locked in with the other two."

"You told him it would be for an hour."

He sipped, smoked, looked back to her. "He will be placed in the room with the other two. The ventilation vents will be closed off. A cyanide pellet will be exploded in the room, injected through the slide-slot, the slot then instantly shut. Death will be quick, merciful, no suffering. Then we'll immediately take off—we four—in the helicopter."

The huge helicopter was there now, waiting, fueled and already packed with their things, on the wide private beach at the rear of the house. The house was a half-mile in from the road. The back had the beach and the ocean; the other three sides had paths, lawns, trees, sculptured gardens. The entire estate was surrounded by a high, iron, picket fence which, in an emergency, could be electrified.

"But why?" she asked again.

"Why what?" Angrily he pushed away the coffee mug; it tilted, then turned over, and the dregs of the coffee spilled. She brought a towel from the kitchen, wiped the table, and took the things away. When she came back he was standing, smiling, leaning against a baby grand piano, smoking a new cigarette. "I'm sorry," he said. His voice was back under control. The dark eyes were now narrow, wrinkled, amused. Softly he said, "What was it we were discussing, my dear?"

"Murder. Senseless murder."

"Murder must never be senseless. That, too, I'd advise you to repeat over and over again. Your second lesson for today."

"But to kill them?"

"Not senseless."

"Why not as you told him? An exchange. Stanley for them. Mr. Solo to be locked in with the other two for an hour. An hour. Two hours. Whatever. Wouldn't that provide our margin for safety?"

"One hour would be enough."

"Then why?"

"We all learn. Even I. We're never too old to learn, not one of us. Just as you're learning today from me, so have I learned from Leslie Tudor. Passion for anonymity. That's not just some stock remark. That's not a bright saying made for the purpose of sounding clever. It has depth, meaning, merit. Anonymity—that's why Albert Stanley was chosen for this job. It has made him unique—his great capacity to blend, to be another blade of grass in an orchard, another tree in a forest, another grain of sand in a desert, to be anonymous, unknown, an unrecognizable part of the whole. Somehow his anonymity failed him; somehow he was recognized; and that made the rest of it easy for them. We don't have to be geniuses to know that. He was recognized, followed, caught in the act doing his work, apprehended. The point is, he was recognized! That resulted in our failure and Leslie's bitter disappointment."

"What's that to do with this?"

"What?" There was annoyance again in Burrows' voice.

"With murder, cold-blooded murder?"

"Anonymity. Not to be recognized. It is a form of self-preservation–even for you, my dear. You are a part of a secret organization, but always remember: Secret is the key word for your very own protection and self-preservation." He moved away from the piano and crushed out his cigarette in an ashtray. "Kuryakin and young Winfield have seen you and have seen me; alive, they can recognize us in the future. No good. Solo has seen Stanley, and he will see me; alive, he can recognize us in the future. No good. The fewer from their side that see and know and can recognize, the safer it is for those of us on our side. Not senseless murder, my dear, not at all."

She shivered. She knew now, finally, what her "cause" had led her into. Up to now she had been an amateur, mouthing words, thinking in abstractions, marching with the students in London, going limp and being carried off into the police vans, shouting deliriously with the others, "Down with the Bomb! Fallout is Failure! We want a Future! Better Red than Dead! Peace! Peace!" And so, with soft words and hard words, she had been recruited to THRUSH, and the hard words were attributed to the enemy, and the soft words had been the words of THRUSH. So she had been won, and had believed, and had even believed that the destruction of the shrines here in America were but steps toward peace. Peace! This was not peace. They had won her, experts had lectured her, and so she had gone with them now on her first endeavor—a professional for peace. Peace! This was not peace! This was crime! And she began to understand. Caught with crime, involved with crime, crime upon crime, there could not be a turning back. These were the professionals using the slogan of peace for the purpose of their professionalism; she was now one of them, a professional, already caught in crime; she had been won to the "cause" by the soft words and was hearing now from Burrows the new words, the hard words from this side, the truth. And she shivered again, crossing her arms, her fingernails pinching her skin.

"What's the matter?" he said.

"It's cold. The air conditioning."

"Yes, the air conditioning," he said, and the dark eyes, narrow, smiling, grew crafty, and he uttered what now in the coldness she knew to be a warning, lecturing sternly, educating her. "We must kill as part of our work. The work of peace cannot always be peaceful. We are soldiers of peace in an army of peace, but we are soldiers. A soldier who defects is a traitor, and the penalty for treason is death. A soldier does not always like his duty, but he obeys orders and does his duty. If not, he is a traitor. There is much he does not understand because, above him, there is a grand plan." Burrows lit another cigarette. "In essence, here, in our own little company, you are a soldier, I am a colonel, Leslie Tudor is the general. I take orders from above, and you take orders from me, and neither of us questions the instructions. We are soldiers fighting in a cause."

"But isn't a soldier—without questioning the orders—allowed to ask questions?"

"Idiocy! I've been answering your questions, haven't I? I'm trying to give you—at this long last—an understanding."

"An understanding about murder?"

"You did not question me about murder. You questioned about senseless murder. I'm against murder, just as you are—against senseless murder. But don't you ever forget that our fight for peace is just that—a fight!—and in a fight people die."

"And those three must die?"

"But not senselessly. On the contrary, quite sensibly—because our own self-preservation is primary. Unless we do preserve ourselves, how can we continue our fight for peace? Sounds pretty—fight for peace–but there's another name to that game, more real but not as pretty; not a pretty little game with pretty little rules; there are no rules at all in that game."

"What game without rules?"

"War," he said. "The name of our game is 'war'."

"Even war has rules."

"Not this war; on our side there are no rules."

"What about the other side?"

"The deuce with the other side. Our concern is only with our side, us! That's lesson three for today, my dear. And now, if you please, I'm bored with giving lessons. Where's Leslie?"

"On the beach by the helicopter."

He clicked his heels, made a mock salute. "Should anybody want me—and nobody will except possibly you—I'm outside with General Tudor arranging the final details."