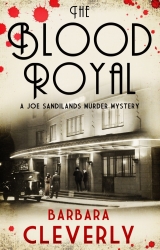

Текст книги "The Blood Royal"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Chapter Ten

‘Two dozen cigarette ends of every kind from Craven “A” to gold-banded special orders. A half-sucked, spat-out, barley sugar sweet. The left leg from a china doll. A stray bullet from Cassandra’s gun. A certain amount of disturbance of the turf.’

Joe read out his list. ‘Just what you’d expect and all meticulously recorded by Superintendent Hopkirk who had the good sense to wait for daylight before he got his fine-tooth comb out.’ He consulted his notes and pointed here and there as they walked the grassed area across the street immediately opposite the admiral’s front door. ‘Something bothering you, Wentworth?’

‘Yes, sir. There is something … We’ve speculated that they must have been waiting here for quite some time … several hours … in a state of considerable tension. I’ve looked and I see no trace of the essential bodily functions one associates with males under pressure in a confined space, sir.’

He gave her an amused look. His men would have reported ‘No sign of anyone pissing under a tree, sir’. If they’d noticed. This girl took the trouble to phrase her suggestions delicately for a male superior. The least he could do was respond in kind. ‘Good Lord! Bladder control! Evidence of lack of it? No sign. You’re right.’

He ran each tree and shrub in review again and grinned. ‘As you say. Nothing of larger capacity than a pug dog has passed this way. No human had a pee in the night. This was their second staging point. They weren’t laid up here for any length of time.’

‘Sir, may I?’ Lily was already running south towards the next clump of shrubs.

Joe had caught up and was peering over her shoulder when she exclaimed and pointed. ‘There – under the large laurel. It didn’t rain in the night so the traces are still evident.’

They scanned the murder scene from this new angle. ‘Timing, Wentworth! It all depends on split-second timing. Let’s test it out, shall we? You’ll have to be the two gunmen and do the running about for me. Most of the curtains on the other side of the road are twitching, d’you see? They’ve probably set their butlers at the windows to watch. If they catch sight of a large man in a black slouch hat racing about in a suspicious manner, they’ll call the police. A woman in uniform won’t raise an eyebrow … You know the script. Ready? Go!’

He watched as his assistant choreographed the incident as she ran, imaginary gun clutched to her side. Bending low, she sought second cover from the trampled patch they had just examined, but only briefly, just allowing time for Lady Dedham to make her way from taxi to front door, then a few more seconds for Lord Dedham to speak to the cabby. Closing in. She counted out a further thirty seconds for distraction time afforded by the appearance of Miss Harriet Hampshire. And how lucky for the assassins that lady’s appearance had been! Under cover of this, Lily ran across the road and sidled down the path to take up position in the forward cover of the bushes near the door.

Joe called her back in his precise soldier’s voice, breaking the spell. ‘That all fits in very well. And I’ll tell you something else. I think that girl – Hampshire – could have been lurking about here as well. You have to look hard to see it but there’s an indentation here in a bit of earth. It’s too narrow to have come from a man’s shoe. It’s quite distinct and very fresh. What do you make of it?’

Lily knelt and peered. ‘The heel of a high-heeled shoe, sir. Evening wear? And why would a girl dressed for a night out be skulking in the shrubbery in this area? Sort of behaviour you expect to come across in Hyde Park after dark but not hereabouts.’ She looked at the faint outline again. ‘There’s a trail.’ Lily squinted and pointed. ‘She arrived from that direction. The house with the closed shutters on the first floor. Someone giving her shelter?’

‘Number thirty-nine.’ Sandilands referred to his notes. ‘Yes. Here we are. Hopkirk took a statement from the butler, a Mr Jonas Warminster. The owner is a gentleman who goes by the even more fanciful name of Ingleby Mountfitchet. Hardly fits the description of a Sinn Fein sympathizer … Mr Mountfitchet, who is a bachelor, ex-army, had retired to bed with his cocoa when he was disturbed by the rumpus that broke out in the street below. The butler assured him that the noise was a car backfiring and his master went back to bed. Where, judging by the tightly closed shutters, he still remains … sleeping something off? Avoiding speaking to us? Yes, Wentworth. I agree. Further and better particulars required, I believe. We should run a check on Mr Mountfitchet. I’ll give instructions to that effect.’ Joe looked up from his notes and said with emphasis: ‘Don’t worry, by the way – basic slog-about police work goes on while we’re here, dancing about in the shrubbery.’

‘Glad to hear it, sir.’ Her response was automatic, her mind elsewhere. ‘Look, sir – no woman would risk ruining her evening shoes and clothes in this wilderness in normal circumstances. She’d walk around on the path.’

‘Meeting someone? Hiding from someone? Lying in wait?’ Sandilands suggested.

Lily stood up again, an object clasped carefully between finger and thumb. ‘Long enough to smoke a cigarette, anyway. There’s lipstick on this. That suggests waiting about. Ambushing? Setting up a diversion?’

Joe produced a paper evidence bag from his pocket and held it open to receive the stub. ‘Not an enthusiastic smoker, evidently. Only a few puffs taken before she threw it away. Interrupted by the arrival of the taxi?’

‘Who do you know who smokes Balkan Sobranie, Holmes?’ Lily asked, laughing at him. She seemed to have been suddenly ambushed by their ridiculous situation.

He answered the question with a grimace: ‘Ah! If only it were so simple in real life. Balkan Sobranie, eh? You’re right. That would reduce our smoker to a select club of about ten thousand émigré Russians and as many Londoners who think it the smart thing to do. Anyone from a grand duchess who screws one into a six-inch-long Fabergé holder to the girlfriend of a Soho waiter who’s decided to have a flirt with the bohemian style.’ He sighed. ‘Still – worth recording and preserving. Perhaps Miss Hampshire will be able to throw a little light? I must check the plans Hopkirk has for re-interviewing that lady.’

‘We’re thinking the same thing, sir? On the same lines as Lady Dedham herself? She was convinced it was a third gun that fired the finishing shot from across the road. And we’re looking at evidence of a third party present at the scene.’

Joe nodded. ‘Yes. Interesting that in all the noise and horror Cassandra picked out a third gun. A killer still at large? I’ll tell you – while you two were upstairs, Hopkirk read out to me over the telephone the initial report from the autopsy. Dr Spilsbury had interesting things to say …’ He took out a notebook and found his place. ‘I give you the salient bits … Hit, in the first instance, by two bullets fired one from the left and one from the right at a distance of no more than six feet. One narrowly missed the lung and crossed the body to lodge in the muscle under his left arm, the other shot penetrated a lung and would, ultimately, have caused death. The coup de grâce was delivered from farther afield and from a higher-calibre gun. Something in the order of a Browning. In the hands of a marksman, I’m inferring from the doc’s comments. Clean shot through the heart. He was dead in seconds.

‘The first two shots came from guns identified as Webleys. As issued by the British army. Thousands of those about on the quiet in London. Old soldiers sometimes fail to turn their weapons in. Conveniently “lose” them. They get used to having protection to hand and can’t bear to give them up. Who am I to blame them – I have an illicit Luger at home myself.’

‘Have you any idea of the distance?’ Lily asked. ‘Of the lethal shot?’

‘Spilsbury’s estimate from an examination of the wound would place the gunman at the edge of the road, right where the taxi was parked.’

‘By someone standing behind and using the motor for cover? Inside it and firing from a window? Or someone at the wheel?’

‘As you say. I think we’ve finished here for the time being, Wentworth. Right – what do you fancy next? Shall I take you to view the wounded at the hospital? I can offer you the butler or the driver, though he was still unconscious when last I heard.’

‘No, sir. I’d really like to have a word with the prisoners, if you can arrange it.’

Joe was taken aback by the request. He looked up and down the street to gain time and his gaze returned to hover inches over her head as he replied doubtfully: ‘I don’t think I can sanction that. No. Not sure it’s a good idea. We’ll leave the interrogation to those who have the skills. Hard nuts these two boyos, according to Hopkirk. All they would offer at Gerard Street was false names. Sean O’Brian and Sean O’Hara if you can believe!’

‘John Smith and John Jones, in other words?’

‘Exactly. No address or comment can be wrung out of them. In view of their intransigence, Hopkirk had them carted off to the Vine Street nick where the officers are more used to dealing with such cases.’

He didn’t think he could make it clearer. Lily, according to her file, was attached to the Vine Street nick. She could hardly be unaware of their reputation. She appeared to select her next remark carefully, her voice controlled. ‘Didn’t you say one of them had a bullet – a .22 from Lady Dedham’s gun – lodged in his back? Wouldn’t one expect him to have been conveyed to hospital for treatment?’

‘A doctor was called in to attend, of course,’ Joe replied briefly, uneasy with the conversation. ‘Anyway, whatever their condition, these are not types a young thing like yourself would want to engage with at any level. I’ve seen them. Brutal killers. Products of the gutter. You’d hardly understand what they were saying anyhow. They’re refusing to speak in English. Leave these things to the experts, Wentworth.’

The constable glowered at him in a silence that rather smacked of contempt. He leaned slightly sideways to look under the brim of her hat. He straightened, snorting and sighing theatrically. ‘I had a cat once that could pull exactly the same face. It got its own way once too often and now features at third on the left in my mother’s pets’ cemetery. Come on then! But on your own head …’

As soon as they’d settled into the back of the squad car Joe began to murmur entertaining nonsense about Vine Street: the West End police station located in a side road off Piccadilly. Notorious to some members of the public, celebrated to others, the view of those receiving attention here was coloured by the seriousness of the charges brought. And by the class and attitude of the miscreant. Drunk and disorderly aristocrats hauled in on Boat Race night would relive their adventures for years to come. The carousing in the cells in the company of like-minded toffs, all caught at a hazardous moment in their wild night out in the capital, led to the formation of new friendships. Over fifty years a certain camaraderie had developed among those who could boast they had survived a night in custody at Vine Street. Over the port, moustached old warriors recounted with a glee equal to that with which they told the stories of their conquests the tale of their night in clink … ‘So there I was, pissed as a newt, caught making mating calls to Landseer’s south-easterly lion in Trafalgar Square … as one does … Thought I was being jolly smart giving my name as the Duke of Wellington, Number One, London, when they chucked me into a cell with – would you believe it? – Field Marshal Haig, Kaiser Bill, Alfred the Great and Jack the Ripper! Of course, next morning Justice Peabody showed his decent side. Let us all off for a fiver each. Except for Kaiser Bill who got charged a tenner for “demonstrating unpatriotic sympathies in his choice of nomenclature”.’

And, however deep the hangover, the wise and drily humorous reprimands of the Justice were always remembered and boringly trotted out verbatim after a passage of decades. One of Joe’s own uncles, he confided, had worked up a hilarious party piece concerning his own incarceration and release, one Ascot week.

The patient professionalism of the arresting officers as well as the understanding of the magistrate presented a comforting image of an England sadly passing and surely to be admired in these dark days, Joe was suggesting. He wondered at his emphasis. A bleaker version of the Vine Street ethos had reached his ears, though much detail was deliberately filtered out before reports were presented to the upper ranks. Unsure what awaited them, he thought it wise to draw a blind of good-hearted humour and irreverence over it for the moment.

The softening up continued as they sped down Piccadilly. Lily nodded and smiled and maintained a polite silence. Her own judgement of the station and its officers had been coloured by a closer experience and from the inside. She had admitted to no one that, on more than one occasion in her year on patrol, she’d held back from calling her colleague to arrest a suspect, out of pity and concern for the latter’s safety in what Sandilands seemed to want to present as a jolly gentlemen’s club. The young, the elderly, the feeble, the first time offenders, Lily reckoned had no place in that brutal environment. No one had caught her pulling her punches and releasing suspects with no more than a flea in their ear and now, she realized with a surge of elation, it was too late for her lapses to be discovered. She was resigning after all. At the end of the day.

‘Prattle on, Sandilands. Who do you think you’re kidding?’ Lily said, but she said it to herself.

Their car dropped them on Piccadilly and Lily set off to the station a few steps ahead of Joe, who paused to give instructions to his driver. She was greeted by the constable on duty at the door. PC Hewitt recognized her and hailed her from a distance with the joviality of a man looking forward to relieving his boredom with an exchange of police banter. Lily was known at the station for giving as good as she got and bearing no grudges. She didn’t look down on the men the way some of those toffee-nosed women did. She could take a joke.

‘Wotcher, Lil! On yer tod today, then? No scrapings from the park to offer us? Just as well. We’re a bit busy – it’s standing room only in there. Bedlam!’

‘Hello, Harry. No, I’m not alone.’ She waved a hand to indicate the presence of Sandilands, who was striding up the side road after her. ‘Not Halliday – he’s gone north. Instead, I bring you the commander. Or he brings me. Not quite sure. But we seem to be together.’

‘Gawd! That’s all we needed!’ PC Hewitt gritted out of the corner of his mouth. ‘What’s Young Lochinvar doing riding up again? Can’t they give him a desk to sit at? And what the ’ell’s ’e want with you?’ Hewitt gave her a look both salacious and speculative.

‘Oh, the usual,’ Lily said lightly. ‘I’m here to provide a little female insight.’

‘Lucky devil! I wonder what you can show him that we can’t?’

Smiling affably, Lily squared up to him. ‘Watch it. How’d you like to greet the boss hopping on one leg? These boots aren’t good for much but they’re damned good kneecappers.’

Hewitt grinned and, playing the game, jumped back, clutching his crotch. The girl had form. There was a sergeant in C division who had the limp to prove it, and gossip had it that the target zone had been some degrees north of kneecaps. He went into a smart salute as Sandilands approached and with a wink for Lily made a play of opening the heavy door with the panache of a hotel commissionaire.

But before they reached the charge room, the oppressive atmosphere of rage, pain, anger and despair had stopped even Sandilands in his tracks.

Chapter Eleven

The hubbub was punctuated by a top note of banshee screams of female outrage and a bass note of drunken singing. Somewhere a Scotsman was growling out the chorus of ‘Loch Lomond’. In the background, cell bells rang every few seconds and the heavy doors to the cell block creaked opened and clanged shut.

Sandilands presented himself to the elderly charge officer, who appeared insulated from the cacophony around him by three feet of shining mahogany counter. He waited for the sergeant to put down his mug of coffee and drop his newspaper to the floor.

‘Afternoon, sergeant. I’m surprised you can concentrate on the racing results with this hullabaloo going on. Stop it, will you?’

‘Sir! Yes, sir! I’d be only too glad to oblige, but, sorry, sir. I can’t, sir.’

There was steel in the commander’s tone as he responded to the affected servility. ‘You’re in charge here, are you not? If you have a superior officer about the place, produce him.’

The sergeant was not easily subdued. He’d seen commanders come and go. ‘Sorry, you’ve got me, sir. Best we can do for you this afternoon.’ His voice revealed a London man secure on his own patch and resenting the intruder. It was only just sufficiently deferential. ‘Nothing I’d like better than a bit o’ peace and quiet like what you ’ave at the Yard,’ he offered blandly. ‘But we’ve got our hands full today, what with the little bit of extra you sent us – those lads requiring a bit of special attention, like. The other prisoners have been backing up. We’re using the common space as an extra charge room.’ He pointed to a second room where a row of six young men sat disconsolately along the wall awaiting interrogation while a pair of constables filled in their details on forms at a large polished table, barking the occasional question at them.

All this was making an unfortunate impression on the commander. His spine straightened to an alarming degree, his height, already impressive, seeming to increase by a couple of inches. He had taken on a sinister stillness.

At last the sergeant became aware that he was running into danger and adjusted his tone. ‘Sorry about the din, sir. That caterwauling’s been going on since the constable arrested her.’ He pointed to a small and dishevelled prostitute who was attempting, between yells, to bite out the throat of the meaty lad holding her stolidly at arm’s length. ‘She’s gone bonkers. Name’s Doris. Tart. Has her beat along the Strand. Regular customer. Bit barmy, but this performance is unusual even for her.’

‘Sarge,’ Lily said, ‘give me a minute with her, will you? I’ve had dealings with Doris before – she knows me. I might be able to sort it out.’

She waited for his nod before making her way over to the wrestling pair. Gently she eased the constable’s grip, inserting herself between the two struggling figures. She leaned and whispered in Doris’s ear. After a stunned silence, Doris’s screams turned to sobs, then sniffles and whimpers. Finally she spoke to Lily in a torrent of words that Sandilands and the sergeant could make neither head nor tail of. It seemed to consist of no more than a list of names: ‘Our Alice, little ’erbert, Georgie …’ Lily nodded, whispered a further question and listened to the outpouring of emotion and fear that followed.

Lily turned to the arresting constable. ‘Tom, fetch me a glass of water, would you?’ While he went off to fetch one, Lily spoke again to the dejected figure before her. ‘I can see what needs to be done, Doris. And the sooner the better. Look – leave it with me, love. I’ll find them, see they’re all right and alert Rhoda. She’s still living in Bradman’s Court, is she? Right you are then. Here, have a drink. Thank you, Tom. Now – you know the routine, Doris. Just go through to the charge room with the constable and do what you have to do. Tom’s new around here – you’ll have to show him the ropes! It’ll be faster in the end. And for Gawd’s sake, gel, keep the squawking bottled.’

Sandilands and the sergeant watched in astonishment as Doris nodded, calmly linked arms with the constable and hurried him into the charge room.

Lily returned to the desk, fire in her eyes. ‘She has four children under the age of six left at home by themselves. She was out earning some cash for their dinner. Her mother would normally look in on the nippers but she’s down with the flu and no one else knows they’re there. The smallest is only nine months old and will be screaming with hunger by now. The oldest is only five and can’t control the toddlers. I’ve promised to go round and stir up a neighbour who might be persuaded to lend a hand. It’ll take about an hour. Will you excuse me, sir?’

She was turning for the door in her eagerness to be off. Sandilands grabbed her by the shoulder. ‘No, I won’t excuse you,’ he said firmly. He fixed the sergeant with a flinty glare. ‘Constable Wentworth is assisting me on a matter of national importance. I will not have her precious time wasted doing social work arising from the incompetence of desk staff.’ He produced a ten-shilling note from his pocket and handed it to the sergeant. ‘Give the woman this and set her loose. You should have more sense than to allow the premises to be cluttered up by trivial, time-wasting cases at a moment of emergency.’

‘Yessir. At once, sir.’ The sergeant followed the pair into the charge room, leaving the door open, handed the note over with a flourish and in a few words explained that Doris was to be bailed immediately, orders of the commander.

As Doris ran off with a backward wave and a mouthed ‘Ta, love!’ for Lily, the sergeant turned again to Sandilands. ‘Wonderful, sir. Glad you called by. Now, would the constable like to deal with Rob Roy in the tam-o’-shanter over there? He’s been making his way back to Loch Lomond for the last two hours.’

‘What’s the charge?’ Sandilands asked.

‘Drunk and disorderly. Could have been grievous bodily harm if we’d been able to make one of the complainants stand and testify. Drunk as a skunk. Caught making lewd gestures with his sporran and assaulting any man he heard talking English in Leicester Square. And that takes a bit of doing nowadays but he managed to find and clobber six before we got hold of him. Down here with his mates for a wedding and got left behind. Officer Smithson who’s grammar school educated and knows what he’s talking about says it’s a Celtic custom. All to do with … stag-worship, I believe he said. The horned god … fecundity … plenty of drink taken … that sort of thing.’

‘I don’t think the Scots need to refer to the calendar before they plan a knees-up. And the many-antlered Cernunnos would hardly recognize our friend as an acolyte,’ Joe added since the sergeant seemed to be partial to a bit of northern folklore. ‘Lord! Let’s hope our chap isn’t the bridegroom. What’s his name?’

‘Doesn’t remember his name or his address. Thick accent – we can’t work out a word he’s saying.’

Sandilands put a hand on Lily’s arm. ‘My turn, I think, Wentworth. You have his belongings, sarge?’

The officer produced a shoe box from under the counter. ‘No calling card, I’m afraid, sir, to give us a clue. Let’s see what we have got.’ He muddled through the items, listing them one by one. ‘Just a small amount of cash, a couple of beer mats, a map of London, a used handkerchief, a ticket stub and a sporranful of confetti.’

Joe held back a flash of impatience as he viewed the contents of the box. These clowns had all they needed to hand and had ignored it. He pounced on the ticket. ‘It doesn’t exactly have his address on it, but this ticket was issued in Glasgow. He came down on a return ticket and this is the all-important return half. What time is the next train to Scotland from King’s Cross?’

‘One every hour, on the half-hour, I think.’ The response was subdued as the sergeant took account of the lapse. He hung his head, waiting for the inevitable reprimand.

It didn’t come. The commander’s tone was encouraging. ‘Right. Then our problems are over. There’s one in twenty minutes. Send one of your blokes with him in a taxi to the station. He’s to be sure to put him on the train and watch him disappear.’ He took out another ten-shilling note. ‘This is for the taxi and any other expenses. Now give him his belongings back and get him out of here.’ He looked about him as the sergeant saw to it and commented drily: ‘Not sure I can afford to know you lot much longer.’

‘Peace and quiet comes at a price around here,’ murmured the sergeant.

‘I’m already enjoying my quid’s worth,’ Joe replied as the great door swung closed and everyone listened in relief to nothing but the distant hum of traffic on Piccadilly.

‘Now, to business,’ he went on. ‘Constable Wentworth wishes to cast an eye on the pair arrested in connection with the shooting of Admiral Dedham last night. You still have them here? I left instructions that they were to be handed on to no one else. Come on, man! You have them?’

The sergeant replied with surprise and reluctance. ‘Yes. Yes. Of course, sir. In the cells.’ He leaned across the counter in a show of confidentiality. ‘Not that we haven’t had offers from other interested parties to take them off our hands, just like you warned us. I stonewalled ’em, of course. Referred them to you, sir. Seemed to work. But, sir, er … Not sure the prisoners are fit to be interviewed in the presence of a lady officer. Rough types. They resisted arrest, of course. And they’ve had an intensive interrogation. They’re resting at present. Getting ready for their day in court. Preliminary hearing at the Old Bailey. No one’s wasting much time over this, eh, sir? Knotting the rope already, you might say …’

Sandilands cut him short. ‘We’ll go through. Five minutes for each man. No more. You are holding them in separate cells?’

‘That’s right, sir. Watch out for the big one. He’s a nasty piece of work. The little ’un’s got no more fight in him. He’ll give no trouble.’ He summoned up a brute-faced copper with hands like ham shanks. ‘PC Kent has established relations of a sort with them. He’s got their number. Kent – take them through to see our Irish friends, will you? And watch out for the lady. And, sir, we’re saying five minutes, tops, with each. If Constable Wentworth can take as much as five minutes.’

They followed Kent through one of the six doors that gave access to the cells. After a great deal of flourishing with the keys and clanging of bolts, Joe entered a step ahead of Lily into the cell of the larger and more aggressive of the two prisoners.

The stench made him reel back. The small space stank of urine, blood, vomit and a disturbing chemical smell that made him retch. The gloom was disorienting. Somewhere in that fetid darkness a form moved slightly and uttered a groan. Focusing on the sound, Joe eventually made out the shape of a man sitting uncomfortably on a narrow metal bench. He was hunched over, clutching his stomach, and paid no attention to their entrance. Was this the assassin? It could have been anyone. His head was sheathed from chin to scalp in a thick layer of bloodstained surgical bandage. Someone had cut a hole around the nose and mouth to allow him to breathe.

With a gesture, Sandilands indicated to Lily that he was allowing her precedence and stood back a pace. Trying to keep her voice level, Lily introduced herself to this nightmare figure and asked: ‘Sean, will you show me your back, please?’

The figure growled and shrank further into the wall.

‘You’ll get no cooperation from him, miss,’ said Kent who was standing protectively at her side. ‘Bullet’s out if that’s what you’re bothered about. Taken away for evidence. The doc had to put him out cold to extract it. Ether it was, to get him to be still. That’s what you can smell. He’s been patched up good and proper. They’ll take him to the hospital when he’s heard his charges.’

The sudden roar from the bandaged head took everyone by surprise. A torrent of abuse in Gaelic poured out. Joe couldn’t understand a word but every one was unmistakably a curse.

Kent put a hand on Lily’s arm and she started at the touch. ‘It’s all right, miss. But I’m afraid that’s all you’re going to get from him. Better come away now.’

The voice came again through the hole in the bandage. Louder. And, alarmingly, it was speaking in English. ‘Not quite all. I have something to offer the lady. Where are you, miss? Not seeing too well … my eyes have been pounded to a pulp.’

The padded head moved slowly from left to right, seeking her out, until she took a step forward and whispered, ‘I’m here.’

Joe’s hands clamped round her upper arms and jerked her backwards out of shot, as, with a spitting hiss, a broken tooth in a gobbet of blood landed at her feet.

Lily was still twitching with shock as Kent locked up the cell behind them. ‘Sorry, miss. Who’d ever have thought it? He must have been saving that up in his cheek. Little offering for the magistrate is probably what he had in mind.’

Joe, embarrassed and uncomfortable, gave her a moment to pull herself together and then asked, confident of her answer: ‘No need to take a look at the other one, I think, Wentworth? Just more of the same.’

‘No, sir, I’d like to see Sean number two if you wouldn’t mind.’

Kent sighed and shrugged and sought out the key for the second cell.

The same sorry spectacle presented itself in here. The same carefully arranged concealing bandages were in place. Sandilands judged they had been applied by the professional hand of a nurse or doctor following the police interrogation.

Kent performed the introductions.

‘Sean – I don’t know if you can see me? No? I’m a woman police officer. I’ve not come to take a statement.’ Her carefully prepared questions ran into the sand as she stared with pity at the small, battered body. ‘I just wondered if there was anything you’d like me to hear. But it doesn’t matter. I’ll go away and leave you in peace.’

The voice spoke in English. English with a London twang. ‘Peace? If only you could. I’m going to hang, aren’t I?’

‘It looks very much like that, Sean. You killed a very distinguished man and a London bobby and left a butler and a cab-driver wounded.’

After a pause: ‘The butler. I’m sorry about him. And the cabby. Wasn’t their business. Just doing their jobs. How are they, miss?’