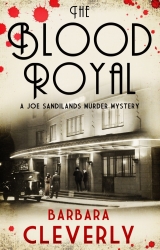

Текст книги "The Blood Royal"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Chapter Twenty-Four

Joe was waiting for them when they returned to the table. ‘Ah! There you are, Lily my dear. All done here for the moment. Time to say goodnight and thank you for having me to these nice people. I want you to come straight back with me now. You’re in for a sleepless night, I’m afraid.’ He took her arm and clamped it under his.

‘Good Lord!’ murmured Connie Beauclerk, watching their hurried departure with sly amusement. ‘Commander Sandilands is very direct, isn’t he? His Scottish cousin, did I hear someone say that girl was? Mmm … a fashionable thing to be, but I do wonder. David, it’s my opinion your new girlfriend’s just been snatched by the dashing detective from the Met – right from under your nose. She surrendered and went quietly – and, gosh! one quite sees why – but you’ve lost her.’

Edward looked thoughtfully down at the wreckage of the table. ‘But I didn’t lose my life, Connie. And I think I was meant to.’

He watched silently as the corpse was taken up in a tablecloth by four strapping young men and carried out of the room.

The commander’s car drew up to the rear entrance as they came out and he handed an exhausted Lily into the deep comfort of the back seat, where she dropped off almost at once. She awoke with a start only minutes later as the car came to a halt at a junction. Guiltily she glanced about her, checking that in her unconscious state she hadn’t lurched into his iron shoulder but had come to rest against the padded upholstery.

Joe thought he’d better reassure her that nothing indecorous had taken place: ‘Lord, Wentworth. You drop off faster than my old Labrador. But you don’t slobber and you don’t wuffle as loudly as he did.’

‘So sorry, sir. How shaming! It’s moving vehicles – they put me to sleep. Limousine or old rattletrap – it makes no difference. The conductor of the forty-two bus had to shake me awake once at the terminus. Are we there yet?’

‘No, not quite. We’ve just passed Chelsea Harbour. I thought we’d get out at Westminster and walk along the river for a stretch. Nice night. We’ll get a bit of fresh air into our lungs before we start work. Must stay sharp for the meeting.’ Moments later, he leaned forward and pulled aside the glass. ‘Sergeant – I want you to drop us off here and go home. Call for me at the Yard at six, will you?’

The driver opened the door and helped Lily on to the pavement. A short way downriver, Big Ben boomed half past some hour or other. Taxis sped by full of people in evening dress; ahead of them a knot of shrieking revellers made a dangerous dash across the street to take a closer look at the Thames.

‘Half past one o’clock and London’s still open for business, lit up and roistering. This is an early night for HRH. Poor chap – he was looking quite done in, I thought, towards the end. Still – he played his part with some skill, don’t you agree? Not easy being the mealy worm on the hook at the end of the line.’

‘I thought him skilful, brave and – yes – charming, sir.’

A mist was rising from the river and its deliciously chill breath made her shiver. She pulled her cashmere wrap more closely about her shoulders and watched as his car made a daring U-turn and set off in the opposite direction. She turned her head abruptly away from the road, annoyed but amused at what she saw, then looked up surreptitiously to see if he’d noticed the car tailing them.

‘I won’t offer an arm,’ he said easily. ‘I’ve noticed you like to stride out. Tell you what I will offer though … we’ve plenty of time before the team starts to assemble. In a hundred yards or so there’ll be another comfort available. Tell me when any food last passed your lips, Wentworth.’

She had to think hard before she remembered. ‘I had a ham sandwich in the Strand, sir. At midday.’

‘Not good enough. I’m sorry for that. You must allow me to make amends.’

She didn’t show any pleasure at his suggestion but pattered resentfully after him. He was about to rethink his offer of a supporting arm but decided against it. She wouldn’t welcome the gesture and wouldn’t quite know how to refuse it.

They marched on in silence, the traffic becoming thicker as they neared Scotland Yard. Joe stopped suddenly when he reached the head of a taxi rank where a long, low building resembling a railway carriage had been constructed. Weatherboarded and painted park-bench green, it had a small black projecting iron stovepipe giving out a blast of coal, smoke and cooking food. A notice over the door declared it to be Licensed Cabman Shelter No. 402.

He put his head round the door and shouted a question. Satisfied with the rumbling response from the interior, he opened the door wider. ‘It’s for cabbies,’ he explained. ‘A sort of revictualling station. These things are everywhere in London but people hardly notice them. They’re not supposed to let just anybody in – they’d lose their licence – but if they get to know you they’ll allow you eat here. Let’s go on board and see what we can find.’

Joe took off his top hat and ducked through the low doorway. Lily followed, stepping from the chilly street into a welcoming fug.

‘Evening, Frank,’ Joe said to the whiskered man behind the counter. ‘I’d like something for this young lady to eat. She’s ravenous. In fact we both are.’

‘Evening, Captain!’ Frank looked pleased to see Joe and if he was taken aback by his white tie and tails he showed no sign of it. ‘Hungry, are you?’

‘I’ll say. We’ve just spent several hours in the restaurant at Claridges, toying with larks’ tongues and picking at plovers’ eggs.’

Frank’s moustache bristled with distaste. ‘Ah. Well, you’ll be needing a Zeppelin in the clouds with onion gravy, then. That’ll stick your ribs together.’

‘That’s sausage and mash, Wentworth.’

Suddenly the idea of sausage and mash made Lily’s eyes gleam. ‘Oh, yes please! That would go down a treat.’

‘Righto. That’ll be two Zeppelins, Frank, and what have you got on for pudding tonight?’

‘Figgy duff to follow, sir, with a dollop of custard?’

Lily’s eyes lit on a cabby spooning up a richly scented pudding and she nodded.

There were two other solid figures in the shelter, steadily eating their way through a substantial serving of something brown and glutinous. They both greeted Sandilands. ‘Evenin’, Captain!’

‘You’re up late,’ said one of them through the steam from a white china cup.

‘No rest for the wicked,’ said Joe, returning the expected reply and enjoying the expected guffaw it produced. And to Lily, ‘Shall we sit over there in the corner?’

As soon as they settled, a large freckled hand descended between them and plates of sausage and mash appeared on the table.

‘Mustard with that, miss? Ketchup? Cup o’ tea?

‘Mustard and a cupper would be grand, Frank,’ said Lily. ‘Milk, one lump, please.’

‘Ah, supper!’ Joe exclaimed in anticipation, picking up his knife and fork. ‘Supper is one of man’s chief pleasures. The other three slip my mind when faced with a banger.’

Lily grinned. She sliced off the crusty end of her sausage first and chewed it with satisfaction, then leaned over to ask, ‘You’re sure this is all right?’

Joe swallowed his sausage and regretfully put down his knife and fork. ‘Well, it is a bit like school dinners, I suppose. But I rather enjoyed school dinners. If you really don’t fancy it, I can think of something else.’

‘No, it’s heavenly. Can’t tell you how much I prefer it to caviar. I meant we don’t risk ruining Frank’s reputation, do we? Look at us. Two refugees from the chorus line of Florodora, still in costume. I wouldn’t want to scare the customers away. It wouldn’t be polite.’

Joe responded to the concern that underlay the light tone. ‘Don’t worry. They’re used to me and my strange ways here, though turning up with a delightful young lady on my arm is not usually one of them. I shall have to put up with a bit of heavy jocularity on that score, I’m afraid. They mostly look on me as a protective presence since I leaned heavily on a street gang that was giving them a bad time. And old Frank’s known me for … oh, it must be going on eight years.’

‘The army?’

Joe nodded. ‘He was in my regiment.’

‘Ah, I understand. You saved his life and he repays you in figgy duffs?’

‘No. You couldn’t be more wrong. It’s to him I owe my life. He’s no more likely to forget it than I am and – I’ll tell you something – you can get rather solicitous and protective of someone whose life you’ve saved, Wentworth,’ he said and added: ‘You’ll find.’

‘I’ll find, sir?’

‘Oh, yes. You’ll be for ever involved – at a personal level now – in the continued well-being of HRH. You’ll scan the Society pages of the press each day to check up on his health. You’ll be concerned by reports that he has a head cold; you’ll offer up a prayer when you hear that he’s strained a fetlock. It’s thanks to you he’s on his way home to York House tonight, hale and hearty, instead of the Royal Hospital, toes turned up, under a shroud.’

She stared at him with sudden insight.

‘Yes. It wasn’t your waltzing feet or protective arms that saved his life – it was your quick thinking and your annoying habit of exceeding your orders that did it.’ Joe reached across the table and patted her arm with a sticky hand. ‘I’m almost certain I know what happened tonight. I’ll say it now because I shan’t be able to pick you out for special commendation when we get to our meeting – well done! I’m not sure how gratified you’ll be to hear me say it – and probably better not tell your father – but this evening it’s my belief you handed the prince his life … on a plate!’

Chapter Twenty-Five

Joe spooned up the last of his pudding and eased back his chair, eyeing Lily silently. She’d been the subject of that calculating stare before and responded by pulling her stole higher over her shoulders, a gesture he acknowledged with amusement. ‘No need for alarm. I was trying to assess the effect you’re going to have on the rest of the male company gathered in the ops room. Yes! I want you to be there!’ He answered her look of alarm. ‘Your evidence is pivotal – but dolled up as you are … well, I’m concerned that the officers present may unwittingly consign to you a somewhat inconsequential role. You look the part, Wentworth – royal girl-friend – flapperish, fox-trotting gadabout. I don’t want to see my men reacting to that image. Most unfair. I’d like you to change.’

‘You mean they won’t take me seriously if I present myself dressed as I was ordered to dress, sir?’

He ignored the rebuke. ‘I know these men. Effective and clever, but women haven’t played a significant part in their lives, I fear.’

‘Oh, I expect they all had a mother, sir,’ Lily said mildly.

‘One can never be certain about Bacchus … Oh, Lord! Bacchus! Give me your impressions when you’ve met him. He’s the handsome dark cove with the heavy moustache. Looks like a Sargent portrait of an Italian peasant, I always think – the hooded eyes follow you round the room saying, “I saw what you just did!”. You may wish to look away.’

She was trying not to laugh at him. ‘Well, I don’t know what effect he has on the enemy, but by God, Bacchus terrifies you, sir. Has he any redeeming human features, this man of mystery?’

‘What, you are about to ask, does he “do for pleasure”? Well, I’ll tell you. Er … he translates stories from the Russian … Pushkin, I think.’

‘Ah.’

‘Into Portuguese.’

After a satisfying moment of disbelief, her laughter burst through.

‘My other men you already know. I’ve called in Hopkirk and Chappel, who are still working on the admiral’s death, and Rupert Fanshawe whom you danced with this evening.’

‘I’d feel easier appearing in uniform.’

‘The meeting’s called for three a.m. I can send you back to your hostel to change. It’s in the Strand, isn’t it? Mrs Turnbull’s ghastly barracks? I’ll put you in a taxi. No – I’d better come with you and face the old dragon myself.’

‘No need for all that, sir. I changed at my aunt’s apartment.’

‘The hat shop lady?’

‘Yes. She lives over the shop in Bruton Street. And don’t worry about a taxi. I’m quite sure I have my own conveyance close by.’

Sandilands raised an eyebrow. ‘Ah! The Pumpkin Express! It’s well after midnight. Are you sure it’ll still be there – the rather eye-catching Buick that’s been following you about all evening? Is that what you have in mind? It was at the Yard. It followed us to the hotel. It followed us from the hotel. It’s been at our heels all along the Embankment.’ He enjoyed her surprise for a moment. ‘I’m expecting it to be cheekily parked in the taxi rank when we leave. Now, tell me, Wentworth – who do you know who drives a cream-coloured American sedan?’

‘My aunt sent me out with her chauffeur, sir. She was concerned for my safety.’

‘Prescient lady! Sandilands? Not to be trusted with nieces. Everyone says so.’ Joe grinned and looked at his wristwatch. ‘You’ve got just over an hour. Long enough?’

‘Ample, sir.’

‘Then I’ll hand you over to … what’s his name?’

‘Albert, sir. Albert Moore. He was a sergeant in the London Regiment.’

The Buick was loitering conspicuously in the middle of a line of shiny black cabs, an exotically striped chameleon poised to lick up a row of beetles.

With a swirl of his cape, Joe approached the driver. ‘Albert Moore? Joe Sandilands … how d’ye do? Glad to see you’re on hand, sarge! Your Miss Lily’s had quite an evening. And so, it would seem, have you.’ He leaned forward, elbows on the lowered window, and said confidentially: ‘But it’s not over yet, I’m afraid. Look – could you take her back to Bruton Street and then on to the Yard? And see our girl doesn’t fall asleep on the back seat. We need her fresh, alert and firing on all cylinders. National emergency on our hands tonight!’

Fresh and alert? Lily paused at the door of the ops room at five minutes to three. Was that how she was feeling? Unexpectedly – yes. She’d got her second wind. A strong cup of coffee from the hands of Aunt Phyl, who’d waited up, had sharpened her wits.

She’d been glad of the older woman’s understanding comments. And her brevity. ‘Back there again? Must be urgent. No – don’t tell me yet. Save it for breakfast. It’ll be a late one – it’s a Sunday. Glad to see the dress has survived the evening intact. I’m assuming the same condition for you, love. I’ve ironed your skirt and put out a fresh blouse and bloomers. Bacon sandwich? No? A bath, then? You’ve just got time. Use the Yardley’s lavender. That’ll spruce you up a treat.’

Smelling sweetly, freshly uniformed, shiny faced, Lily knocked and entered, to find that the men were already in place. All rose politely to their feet. Five pairs of eyes watched her as she came in, some inquisitive, some hostile. Sandilands and Fanshawe were still in evening dress, the outer layers removed, collars discreetly loosened, waistcoats unbuttoned. The other three were in their smart city suits ready for the day.

‘Right on time, constable. We’ve saved you a place over there.’ Sandilands greeted her with an expansive gesture. He indicated a seat opposite him at the end of the table.

‘Settle down, everyone. Now – Miss Wentworth, I don’t believe you’ve met our James Bacchus, have you?’

Sensing that there was no time for a formal presentation, the Branch man and the constable nodded cordially at each other across the table. Lily registered quiet dark eyes above a large nose and a top lip so exuberantly moustached she had the impression that a small but hairy rodent had climbed aboard his upper lip and gone to sleep there. She found she was smiling at him and receiving a raised eyebrow in return.

‘Now then – we all know who we are, I believe? You’ll remember Miss Wentworth? And you know why she’s here. First I’ll update you on the Prince of Wales. He is safely back in his London home, unscathed, and will tomorrow be whisked away to the country – to an as yet undisclosed location – to stay with friends. The press will publish the usual false information concerning his whereabouts.’ He cocked an eyebrow at Bacchus, who nodded confirmation. ‘And, to go on – it’s likely we are contemplating a case of murder. We await the post-mortem report, of course, but according to the medical authority who was present at the scene, the victim died of poisoning. Potassium cyanide.’

The Branch men pursed their lips. A heavy silence fell.

Wondering at this sudden paralysis, Lily was struck by a sudden insight and kicked herself for not having made the deduction earlier: she was the only person at the table who was not feeling some measure of doubt and self-recrimination. Her excitement must have dulled her perceptions. Tonight, a man had fallen dead under their very noses and his death would have to be explained. As would the apparently fortuitous escape of the Prince of Wales. Someone would have to tell His Royal Highness how close he had come to a sudden and agonizing end. That the man he had witnessed writhing in agony at his feet was his stand-in.

Not only was there a crime to be solved, there was negligence to be accounted for. Blame to be assigned. And – here it was again – a career to be lost.

Which of these men would end the evening taking the blame? She calculated that whoever emerged as scapegoat would have the doubtful comfort of being accompanied into the wilderness by Sandilands – if the commander stuck to his form of shouldering responsibility. Hopkirk and Chappel, though evidently concerned, were most probably in the clear, she concluded, guided by her scanty knowledge of police politics. This had not been a CID operation. At all events, two of these five officers would not survive the night, Lily reckoned. Sandilands and …? She glanced around the stony faces and came to a sad conclusion.

Her selected candidate looked up at that moment, caught her eye, caught her thought, and scowled.

‘The question is – was the Serbian prince, Gustavus, the intended victim or did he barge in and accidentally consume poison meant for our own Prince of Wales? We must consider both possibilities. Either way, this is a task for the Branch. The dead man was a foreigner of doubtful origin and uncertain political leanings – you have a file on him, Bacchus?’

‘We have, sir. I’ll pass around a few copies for information.’

At this point, Lily, to her embarrassment, found that she’d raised her hand to catch teacher’s attention. Someone failed to repress a scoffing grunt.

‘Yes, Wentworth?’

‘The victim’s wife confided to me in the powder room that he is … was … “an impostor”, sir. That’s the exact word she used. I questioned her usage and she confirmed that she meant what she said.’

‘Interesting. Possible impersonation. Are we surprised? Lot of that sort of thing about in London town these days. Impostor, eh? We’ll take this up again with the Princess Zinia, whoever she may be. Takes one to know one, possibly. I’m aware that these jokers tend to work in pairs. Let’s admit, gentlemen – it would be greatly to our advantage if we could reveal the so-called Prince Gustavus to be a charlatan.’ He smiled round the table. ‘Even better if his evening suit should prove to have something interesting in the lining … like a slender garotting wire or a slim package of some white powder. Yes, Bacchus, a path worth pursuing. See what you can come up with.’

Bacchus gave a wry grimace in response and made a note.

‘And we’re considering the attempted assassination of a member of our own royal family. This also is in your purview, Bacchus. We’ll only get to the bottom of it by establishing just how the poison was administered. We’ll trace the events backwards. Rupert – you and I were sitting right there at the table when the Serbian succumbed. Much to our discredit. Miss Wentworth was, at the crucial time, performing her duty down below in the ladies’ room, and only surfaced to witness the last moments of the tragedy. Rupert, I want you to give the company an idea of what transpired.’

A knock at the door sent them all silent. A constable entered with a large brown envelope in his hand. ‘Sir, a newsman called in at reception. He said you’d be needing these. Top priority, he said.’

‘Indeed! Thank you, constable. Leave it on the table, would you?’

Sandilands opened the envelope and spent some moments inspecting the contents. ‘As good as police efforts,’ he commented. ‘No – better. We’ll start by reminding ourselves of the evening’s work – here’s a photograph of the POW at the start of the proceedings, safely in the arms of the Met.’ He paused for a moment, studying the print. ‘Goodness me! Whatever were you doing with him, Wentworth?’

‘A waltz, sir,’ Lily confirmed as Cyril’s deliberately glamorous photograph circulated to astonished stares from the CID men.

‘And he survives to waltz another day – let’s keep that in mind. And here’s a useful shot of the company at the table before the event.’ He paused, absorbed by the next subject. ‘Followed by a society pose showing our victim – scarred cheek, shifty grin – in the close and apparently friendly company of the POW.’

Rupert shuddered. ‘We should have picked him up and marched him straight out, sir. We sat there and watched.’

‘Your anxiety is shared, Fanshawe. But remember Gustavus was there at the Prince of Wales’s invitation. Let’s not indulge in unwarranted breast-beating; we were reacting to the social demands of the situation. This is not a police state. Our role is to advise and protect. We do not pick up and march out a gentleman who has been invited to seat himself at the prince’s table. We had both arrived at the same assessment: that there was no threat to the Prince of Wales’s well-being. Gustavus was unarmed. He’d been searched. He was surrounded by security officers – one false move and he’d have been rendered harmless. And he knew that. Rather tormented us with his heavy-footed humour on that score. He was revelling in the attention, you’d say. And enjoying cosying up to the prince.’

‘Sir!’ Lily spoke swiftly. ‘Again, his wife has an explanation. No sinister political motive involved – she claimed that he was seeking proximity for purposes of social aggrandizement. He just wanted his photo in the press … posing with the prince, on the front page of the society journals.’

Rupert groaned. ‘They will do it! I’ll make that steward account for the bulge in his back pocket.’

Sandilands nodded and carried on. ‘Now here’s a view of the table as it was at the moment Prince Gustavus sank gargling from view on the far side. The plates and glasses – I want you to consider them. The contents have been bagged and bottled and are at present at the lab undergoing the usual tests. Rupert – take us through it.’

‘The far side, where you see a half-full glass of wine, was the POW’s place. Next to him, on his right hand, where you see an empty glass, was the place Miss Wentworth had originally occupied. In her absence, Gustavus, finding the effort of shouting in Serbian from his original place over the table too demanding, had sidled round, taking his glass with him, and plonked himself in Wentworth’s vacated seat. He had previously turned down offers to have food fetched but had consumed a quantity of wine.’

Sandilands took over. ‘Aided in his consumption by the copious amounts poured out for him by Fanshawe here. What exactly were you hoping to achieve by that, Fanshawe?’

‘I thought I’d achieved my end, sir.’ Fanshawe’s tone was truculent and resentful. ‘I was trying to incapacitate the ghastly fellow. He tried several times to reveal secrets he ought never to have been in possession of. You heard him. Miss Wentworth may have branded him an impostor – whatever she means by that Boy’s Own Paper designation – but he showed a certain depth of knowledge of our services’ operations. Showing off for the prince, of course, but there were other receptive ears in the neighbourhood. It seemed the only way of silencing him. No one believes a word uttered by a man in his cups. Rendering the subject harmless, sir, that’s what I was doing. As no one else seemed about to take it upon himself,’ he added rebelliously. ‘It was hardly believable, the gross behaviour the man exhibited, but he caught sight of Miss Wentworth’s full plate – she had to my notice not attempted so much as a forkful – and began to dig in. He clearly couldn’t resist the red caviar – he started with that.’

Inspector Chappel grimaced. ‘Well, they say that Rasputin of theirs had the table manners of a hog and the appetite of a brown bear. Must be the cold winters that do it.’

‘Not immediately, but several forkfuls later, in mid-sentence, mouth still full of food, he keeled over.’ Rupert pushed on with his account. ‘Choking, red in the face, unable to breathe, clutching his heart. All the symptoms of a heart attack or cyanide poisoning.’

‘And I can confirm the latter. In attempting to resuscitate him, I’m sure I detected a strong scent of almonds on his breath,’ Sandilands said.

‘Sir, one of the dishes – the fricassee of Persian lamb – had almonds amongst its ingredients,’ Lily offered.

‘As well as all the spices of the orient. As good a way as any of disguising the scent of cyanide. I took some of that dish myself. Like many others now snoring peacefully in their beds,’ he added thoughtfully. ‘So – by mistakenly eating from Miss Wentworth’s plate, the Serbian signed his death warrant.’

‘Er … No chance, I suppose, that anyone would be targeting Miss Wentworth herself?’ Chappel asked sheepishly. ‘I know, I know – it sounds ridiculous, but training makes me bring it forward. Purposes of elimination and all that … clear out the underbrush. She was the one who was handed the poisoned plate, after all. Got to consider it!’

‘A reasonable thought, Chappel …’ Rupert Fanshawe allowed, ‘if we must plod every tedious inch of the pedestrian way to the truth. But – and this will come as a surprise to you fellows – Miss Wentworth was not, in fact, the one who was handed the poisoned plate.’

He waited for the astonished stares then carried on, his voice purring with anticipation: ‘And, as long as the spot-light’s on the constable, may I suggest we follow up with a further reasonable thought? We should remind ourselves that what we are seeking in all this is a malign female presence. An unknown woman on assassination bent. Our Morrigan.’ He turned a sweet smile on Lily. ‘Now, Miss Wentworth was the woman closest to the Prince of Wales from beginning to abrupt end and she had continuous access to him. We, gentlemen, had placed our prince in the hands of a stranger for the whole evening. A stranger to him … a stranger to us. Can any one of us claim to know who she is? Where she comes from? Who precisely stands as her guarantor? Oh, I am much to blame. I should have taken immediate action.’ He shook his head to underline his self-recrimination. ‘If only I had acted in accordance with my training and arrested Miss Wentworth the moment it became clear that her behaviour at the buffet was suspicious, we could have avoided a murder.’

‘Eh? What are you on about?’ Lily murmured.

‘Suspicious behaviour? Describe it, Fanshawe.’ Sandilands was peremptory.

Fanshawe enjoyed the incredulity for a moment. ‘I watched as the food was being put out. I watched as Wentworth followed the prince to a table. There she snatched his plate from him and replaced it with her own. Oh, it was neatly done. But the movement was not in the briefing. It exceeded instructions. It was surreptitious and possibly suspect. We were at the ball to prevent a young woman – a young woman with certain social graces – “Mayfair”, I believe, was the Assistant Commissioner’s judgement – from getting close enough to the prince to kill him. And here was one such sitting by his side and forcing the food of her choice on the prince with all the skill of a music-hall card sharp. She could easily have anointed the oysters with something nasty held in her hand. If I’d made a fuss and had both plates taken away at that moment, the poison would have been discovered there and then. And Prince Gustavus would still be alive. You have my unqualified apology, sir.’

Rupert drooped then raised his head in defiance. He swept his floppy blond quiff off his forehead, the better to stun them with his blue eyes ablaze with an emotion which clearly anticipated a coming martyrdom. ‘I’m ready to accept whatever proportion of blame you care to assign to me, sir.’ And he added coldly into the shocked silence: ‘After you’ve chucked the book at Wentworth.’

Lily shivered, devastated by the implications. The two plates had been exactly alike. If Fanshawe had proceeded with the scheme he’d just outlined there was every chance the plates would have been confused on their way to the laboratory. Intentionally or accidentally. Who would ever know? She wouldn’t have been able to distinguish them herself. Both carried her fingerprints and those of the prince. Accusations would have been made. From what they’d stitched together of her background she knew they could make a spectacularly convincing case against her. ‘Left-wing, anti-royalist, worms her way into the Royal Presence …’ Poison was known to be a woman’s choice of weapon.

A pit of horror opened up before her. If they were seeking an easy suspect to cover for their incompetence, she would find herself occupying a cell in Vine Street within the hour. She looked instinctively to the commander for support.

Her appeal went unacknowledged. He was watching Fanshawe, head on one side, quizzical, encouraging him to go further. It occurred to her – and the realization hit her like a thump in the stomach – that for these men, all of whom had a position to lose, the career, the life even, of a lowly woman policeman on the point of leaving the service anyway would count for little. She was expendable. They were officers. Ex-military. It was men of their kind who’d sent out Tommies to die in their thousands on the Somme. She too was no more than cannon fodder.

She’d been sitting here playing eeny meeny miney mo, choosing the unlucky victim, never thinking to enter her own name in the draw. If these five men were to behave in concert she was ruined. And there was every sign that, with Sandilands acting as ringmaster, they were coming to an understanding.