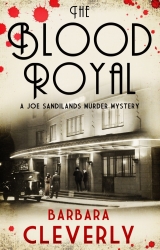

Текст книги "The Blood Royal"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

Chapter Four

September 1922

In the warm intimacy of the rear seat of a London cab, Admiral Lord Dedham stretched out his long legs and adjusted the scabbard of his dress sword so as to be sure not to snag the trailing chiffon gown of the woman by his side. It had been a long, hot evening filled with far too many blood-stirring speeches – the most incendiary of them coming from his own lips, he readily admitted. He’d received a standing ovation and that sort of thing always went to the head however tight one’s grip on reality; he’d taken on board too much adulation and too many drinks for comfort. He was longing for the moment, soon approaching, when he could relieve his chest of its cargo of medals and slip out of his much-bedecked dress uniform.

But until that blissful moment arrived, he was more than content with the present one. Even at his time of life – which he thought of as ‘vigorous middle age’ – the admiral still found that the capsule of darkness to be found in the back of a taxi, lightly scented with gardenia, good cigars and leather, sliding secretly through the roistering crowds of central London, had its enlivening effect. It had been even more invigorating in the swaying hansom cabs of his youth but his ageing bones could never regret all that bouncing about over cobbles. He reached out and seized the white-gloved hand left invitingly close to his on the banquette and lifted it to his lips with practised gallantry, a wary eye on the driver.

The observant cabby’s eyes gleamed in the rear-viewing mirror, his shoulders shook perceptibly and he launched into a cheery offering from Chu Chin Chow.

Lord Dedham had seen the musical extravaganza three times. It was his favourite musical comedy. He recognized the sumptuously romantic duet ‘Any Time’s Kissing Time’.

Cheeky blighter, Dedham thought, with an indulgent grin. Typical London cabby. Ought to be keeping his eyes on the road, not spying on his passengers. He wondered if his companion would take offence. Many women would.

His companion responded to the effrontery by leaning mischievously towards the admiral and biting his ear, her aim, in the dark, surprisingly sure. Then she joined in with the song, timing her entrance perfectly, weaving her clear soprano voice into the chorus to sing along with the cabby.

‘Nearly there, my love,’ growled Dedham. ‘Did you ask Peterson to wait up?’

‘As though he’d agree to do otherwise, Oliver! He’ll be there waiting with your eggnog at the ready. But I dismissed your valet. I’ll help you out of that clanking regalia myself.’ And, as though the promise of eggnog and wifely ministrations was not enough to stiffen the sinews, she squeezed his arm as they turned from the hurly-burly of Buckingham Palace Road into the quiet opulence of the streets approaching Melton Square. ‘Oh, it’s so good to have you home again, darling, and I shall go on saying that until you beg me to stop. And when we arrive, you will remember to do as Joe told you, won’t you?’

‘Dash it all, Cassandra, we’re in Belgravia not Belfast!’ he objected.

Lady Dedham quelled her husband’s predictable splutterings by her usual method of putting a finger firmly over his mouth. ‘And thank God for that! But your young friend at the Yard is worth hearing. It’s a very simple arrangement. It makes complete sense. We must prepare ourselves to observe this routine until all the unpleasantness blows over or you and that fire-eater Churchill stop making sabre-rattling speeches, darling, whichever is the sooner. Yo u it was who insisted on dismissing the police protection squad Joe kindly set up for you, and now you must perform your part of the bargain.’

‘Protection squad!’ The admiral spat out his derision.

‘He didn’t have to do that, you know – over and above his duty. You’re an ungrateful piggy-wig, Oliver. You listen to no one. I can’t think why you objected. Those Branch men he sent round were terribly discreet … really, you’d no idea they were there. And the young one was incredibly handsome! I was so enjoying having him about the place. He cheered us all up.’ She weathered his splutter of outrage and sailed on. ‘But you agreed to the commander’s alternative proposals and I for one shall hold you to your promise. I have a part too, you know, and I fully intend to play it. I expect nothing less from you. Now – tell the driver what you want him to do. And don’t cut it short – I shall be listening!’

The taxi pulled up in front of a late Georgian house on the northern side of the park-like boulevard that was Melton Square. Heavily porticoed balconies and densely planted patches of garden gave these houses an air of discreet dignity. Dedham looked about him with satisfaction at the solid grandeur, the sedate Englishness, the well-lit pavements, of what he considered to be the heart of London. Nothing truly stirring had happened, in public at least, here in the Five Fields since the Earl of Harrington’s cook had been set upon and beaten to death by highwaymen a century before. Since the arrival of the gas-lamps, the only crimes hereabouts were committed behind closed doors by the inhabitants themselves and went unrecorded unless, chiming with the spirit of the times, they gave rise to an ennoblement of some sort for the perpetrator. There were more rich, influential villains per square yard here in this genteel quarter than in Westminster, the admiral always reckoned.

He frowned to see one of these approaching. A gent in evening dress, opera cape about his shoulders, top hat at a louche angle over his forehead, was weaving his way uncertainly along the pavement.

‘I say, Cassie.’ He drew his wife’s attention to the staggering figure. ‘Who’s this? Do we know him? He looks familiar.’

‘He is familiar! Look away at once, Oliver!’ Cassandra put up a hand, seized his chin and turned his head from the window. ‘I forget you scarcely know your own neighbours. But that’s ghastly old Chepstow. Drunk as a lord again!’

‘If that’s Chepstow he is a lord,’ objected Dedham, trying to turn for a better view. ‘He’s entitled, you might say.’

‘It’s no joke, Oliver! Stay still and give him time to move off. He’ll recognize you. And you’re the one man in London everyone – drunk or sober – wants to talk to and shake hands with. You really have no idea, have you? You’re twice a hero now, you know. He’d expect to be invited in for a nightcap. Darling, you’ve been away from me for six months! I’ve no intention of sharing you with any old toper.’ She pulled his head down into an enthusiastic kiss. ‘Ah … there he goes … Now, Oliver – the cabby’s waiting. Get on with the briefing.’

The driver had been grinning in understanding throughout the conversation. He seemed to have a sense of humour and Dedham prepared himself for a sarcastic response to the guff he was about to spout. However, the man accepted his fare and the generous tip he usually enjoyed from the denizens of these fifteen square acres and listened, head tilted in an attitude of exaggerated attention, to the request that came with it. He nodded when the briefing was over and returned a simple ‘Understood, sir’ in response to the crisp naval tones.

As instructed, he hooted twice and waited for thirty seconds before winking his headlights three times. He even managed to keep a straight face throughout the proceedings. ‘There we are, sir. Signal acknowledged. Light’s come on in the vestibule,’ he said, enjoying the game. ‘And the front door’s opening. Here we go! Time for the lady to make her sortie.’

With a snort of amusement Lord Dedham understood that the man had been listening as his wife rehearsed him in his exit tactics.

‘Road’s clear and well lit, sir, no suspicious persons or obstacles in sight, but I’ll get out, take a quick recce and then launch the lady.’ The driver had suddenly about him the briskness and wariness of an old soldier. ‘Just in case. You never know who’s lurking in the shrubbery these days.’

He got out and walked up the path, peering into the bushes. He kicked out at an innocent laurel or two before returning to the rear of his motor to open up for Lady Dedham.

‘Fire Torpedo One!’ she said with a grin for the cabby and, clutching her evening bag tightly in her right hand, she walked off quickly towards the front door the butler was holding wide in welcome. She turned on the doorstep and gave a merry wave.

Before the driver could fire his second charge, a slight form dashed across the street and accosted him. ‘A taxi! What luck. In fact, the first stroke of luck I’ve had tonight. Park Lane please, cabby. Pink’s Hotel – do you know it? And fast if you wouldn’t mind.’ The stranger fiddled around, tugging open with nervous fingers the velvet evening bag she carried dangling from one wrist. She exclaimed with frustration as a handful of coins fell clinking to the ground, and her thanks to the cabby, who scrambled on his knees to retrieve them in the dark, were embarrassed and voluble. Her discomfort increased when she caught sight of Lord Dedham’s legs reaching for the pavement. ‘Oh, frightfully sorry! Cabby – you already have a fare?’

‘Don’t worry, miss!’ Dedham’s reassuring voice boomed out. ‘Leaving, not entering. It takes a while to get my two old legs working in concert. You may drive straight on, cabby. As soon as I’ve disembarked my old carcass.’

‘But you told me just now to wait until—’

Lord Dedham cut him off. ‘Nonsense! The lady’s in a hurry. Take her where she wants to go.’

He accepted an arm in support from the grateful young girl and struggled out, shaking down his uniform and straightening his sword. Very pretty, he thought, with a sideways glance at the slender figure under its satin evening coat and the pure profile set off by the head-hugging feathered hat. He wondered with amused speculation from which of his well-to-do neighbours she could be running away. Not a difficult question: it must be that bounder Ingleby Mountfitchet at number 39. She’d appeared from that direction and was casting anxious glances back towards his house. Dedham followed her gaze with chivalrous challenge. It wouldn’t be the first time a girl had fled screeching in the night from that cad’s clutches. If rumour was right he’d been kicked out of his regiment. And it would seem that in civvie street his conduct continued to be unbecoming of a gentleman. High time someone took him by the scruff of his scrawny neck and told him that sort of behaviour would not be tolerated in this part of town. Dedham resolved that neighbourly questions would be asked. By him. In the morning.

He walked the few yards to his door, smiling, eager to share his piece of salty gossip with his wife.

He reached the doorstep and greeted his butler with an affectionate bellow. ‘There you are, Peterson. All’s well with us, you see. We’ve survived the evening. Though it was touch and go at one point – her ladyship nearly died of boredom. During one of my own speeches!’ The expected joking sally was the last intelligible pronouncement the admiral uttered.

Two dark-clad figures crept from the laurel bushes. One called out the admiral’s name. When he spun round, identifying himself, they took up position with professional stealth, a man on each side of the doorstep. Both men fired at the same time.

‘Service Webleys,’ the admiral had time to note before, caught in the cross-fire, he was struck by two bullets in the chest.

An onlooker would have concluded, from the victim’s reaction, that the shots had missed their target. Oblivious of his wounds, he strode back outside with a roar of outrage and drew his sword from its scabbard.

The man who had commanded the fire-power of a dozen twelve-inch guns and a crew of seven hundred aboard a battlecruiser in the North Sea now found himself fighting for his life with a dress sword, alone on his own doorstep, but he laid about him with no less relish, attacking by instinct first the larger, more menacing of the pair. He caught him a slicing blow to the cheek. A combat sword in fine fettle would have split the man’s face in two, but, despite the blunt edge, the admiral was encouraged to see he’d drawn blood. Delighted by the howl of pain he’d provoked, he went for the smaller man, chopping at his gun hand.

A third bullet hit Dedham in the heart.

His sword clattered to the paving and he folded at the knees, collapsing sideways into the arms of his wife. Unconcerned for her own safety, Cassandra had run back to her husband and knelt by his side, supporting him with her left arm. He opened his lips to whisper ‘Kiss me, Cassie’ as he’d often joked that he would in a playful tribute to his hero, Lord Nelson, should he be laid low and preparing for death. But no words would come. He couldn’t seem to draw breath. And Cassandra’s attention was elsewhere. With a croak of astonishment, the admiral blinked to see his wife freeing her right hand from her bag. Unaccountably, the hand he’d so recently fondled in the taxi now held a small pistol which she fired off, shot after purposeful shot, at the fleeing pair. Her scream of encouragement to the butler rang in his ears: ‘After them! Stop the ruffian scum, Peterson!’

Lord Dedham smiled admiringly up at her and his eyes closed on the sight of his wife taking careful aim down the barrel of her Beretta.

The two gunmen raced to the taxi, firing backwards over their shoulders at Peterson who chased after them armed with nothing but fury and his bare hands. They bundled themselves into the back seat next to the shrieking woman in the feathered hat. Unsurprisingly, she rapidly made space for them and their guns on the back seat.

Hit in the shoulder and leg and bleeding on to the pavement, the butler raised his head and watched as the motor erupted into a three-point turn. In his agitation, the driver seemed to clash his gears and the car ground to a juddering halt, its rear licence plate clearly in view in the light of the lamp. Peterson focused, stared and repeated the number to himself.

In the distance a police whistle sounded and the boots of the beat bobby pounded along the pavement. Peterson called out faintly.

At last, the taxi screeched off with a great deal of revving but little forward momentum.

The turbulence in the back seat threw up a stink of sweat, the iron odour of blood and a reek of cordite. This noxious cocktail was accompanied by a gabbling argument in a language the driver could not understand. But rage soon expressed itself in plain English. ‘Stop farting about, you bastard! Drive!’ the larger of the two men snarled. ‘To Paddington station. Fast. Miss one more gear and you get it in the neck yourself. Like this.’ He pulled back his gun to point it ahead through the open window at the beat bobby who had placed himself squarely in the road in front of the taxi, one hand holding a whistle to his mouth, the other raised in the traffic-stopping gesture. This calm Colossus held his position as the taxi came on, impregnable in his authority.

Two shots sent the imposing figure crashing on to the road.

The cabby swerved violently and deftly mounted the pavement to avoid running over the body.

‘Leave it to me, sir,’ he said, apparently unperturbed by the hot gun-barrel now boring into his flesh. ‘I know these streets like the back of my hand. We’ll go the quickest way.’ And, light but reassuring: ‘Don’t you worry, sir – I’ll get you to the station all right.’

Chapter Five

Joe looked up from his notes and ran a hand over his bristly chin. He blinked and focused wearily on his secretary across the desk. ‘Who did you say, Jameson? Constable Wentworth? Oh, Lord! My nine o’clock interview. Didn’t I say she was to be intercepted and her appointment deferred?’

‘Well, she’s sitting out there now in the corridor, sir, large as life. I’ve no idea how she managed to sneak past them at Reception. I did tell them.’ Miss Jameson dabbed at her eyes with a damp handkerchief. ‘Today of all days!’ She gulped and sniffed in distress. ‘We’ve got quite enough on our plate. She’s only been summoned to hear her dismissal. I’ll tell her to go away and come back later. A week here or there can’t signify.’

‘No. Wait a moment.’ He pulled towards him a file bearing the constable’s name and number. It also sported an ominous red tag.

Discharge.

Notice of termination of employment with His Majesty’s Metropolitan Police. Announcing that an officer was surplus to requirements was always a difficult duty when not deserved and, as far as Joe was aware, none of the women did deserve dismissal. Mostly, they left with relief to get married or because their ankles swelled. When the austerity cuts demanded it, he had chosen to break the news to the men himself, rather than expose them to the abrupt, acerbic style of the Assistant Commissioner whose job it normally was, but had left the women to be dealt with by a high-ranking female officer like his cousin Margery Stewart, better acquainted with the subject and better equipped by nature with a comforting shoulder to cry on.

The young woman waiting outside was a special case, however. And time was running short.

The decisions arrived at in last month’s Gratton Court conference Joe now saw had been right and timely. With a grim irony, it had been Admiral Dedham himself who had argued against them and, outvoted at the time, had immediately set about dismantling the sensible schemes. After last night’s tragedy, it fell now to Joe to reinvigorate the plans without delay, before worse occurred. Before much worse occurred. His deadline was a week on Saturday. Not long enough.

‘Bring her in, Miss Jameson. I do need to see her. Might as well get it over and done with.’

While Miss Jameson’s back was turned, he slipped the red marker off the file, considered throwing it away in the bin, then put it in his pocket. The outcome of this interview was by no means certain. And, whatever the result, he had an unpleasant task ahead of him, a task imposed upon him by a pincer movement from above. At Gratton he’d found the courage to make his views clear and they’d heard him out but in the end, as the youngest and least experienced of the assembled strategists, he’d been overruled. Politely, he’d been made aware that his role was one of … what had Churchill said? … implementation, not grand design.

‘Cat’s paw.’ Lydia had it right, as ever. If all went well, they would take the credit. If disaster followed, Sandilands would carry the can.

Joe screwed his eyes closed and conjured up without too much difficulty the face that went with the number on the file. It had made quite an impression on him. The station platform. Smoke and noise. And in the middle of the mêlée, a pretty girl grinning in triumph. Under her bottom one of the West End’s nastiest specimens and in her hat a jaunty rose. Joe smiled as he remembered the scene. He recalled watching the tiger-like silence of the stalk, the swift pounce, the fearless attack. He hadn’t forgotten the eager rush of gratitude for his intervention, delivered in an attractive, low voice. The constable could well be the best England had to offer in the way of womanhood, he thought with a rush of sentimental pride.

And that was something he would have to eradicate from his thinking in this job: Edwardian gallantry. There could be no place for the finer feelings in this ghastly modern world. Chivalry itself had fallen victim to bloody-handed assassins, if he read the situation aright.

Yes, this had to be the right girl. If he were minded to preachify, he might even say that Fate had delivered her into his hands that day at Paddington.

And the next day down in Devon, he had delivered her into the hands of three of the most ruthless men in the land.

‘Look no further, gentlemen,’ he’d said, after a second glass of port. ‘If this is really what you are prepared to do, I think I may I have the very girl for you.’ He’d even announced her name and number. Satisfyingly, eyebrows had been raised, grunts and nods of encouragement had broken out. Warmed by the general approval, he’d undertaken to haul her aboard.

Joe shuddered. He’d saved her from a knifing at Paddington but had probably exposed her to a worse fate.

He’d have to play his cards carefully. He could take nothing and no one for granted. This wasn’t the army where orders were given, received and blindly obeyed. The woman was perfectly free to reject his overtures and scoff at his suggestions. And foul up some well-laid plans.

Lily Wentworth followed Miss Jameson into the room and looked about her. Astutely anticipating a dismissal committee, he guessed. Her eyes rested briefly on him, widened in surprise, narrowed again in distaste and slid down to her boots. Well, if she’d been expecting to see the knight-errant from Paddington, all smiles and panache, she was going to be disappointed this morning; what she’d got was a Sandilands sore and seething with rage. He realized that in his dark-jowled state he presented an unappetizing sight. With not a minute to dash to his Chelsea flat and change, he’d resorted to a quick cold splash in the gents’ washbasins an hour ago. He’d stared back in dismay at his image in the mirror: black stubble, red eyes, and a dark tan looking unhealthily dirty in the morning light, as well as throwing sinister emphasis on the silver tracery of an old shrapnel wound across his forehead. If he’d encountered that face in Seven Dials, he’d have clapped the cuffs on and searched the owner’s pockets for a stiletto.

The cold wash hadn’t gone far towards dispelling the night’s build-up of fatigue and filth. He glanced down at his blood-stained tie and cuffs. His attempts to dab them clean had not been entirely successful. Whose blood? It could have been from any or all of the four victims. Ah, well … she’d probably seen worse down the Mile End Road at chucking-out time on a Saturday night. No need to draw attention to it. He rose to his feet and came round his desk to greet her.

‘That will be all, thank you, Miss Jameson,’ he said genially enough. ‘Go and get yourself a cup of tea or something. You look as though you could do with one. Oh, and while you’re at it, remind PC Jones I haven’t had mine yet. Tell him to bring a tray. Two cups. Milk and sugar. Biscuits too – gypsy creams would be good – not that dog kibble he brought me yesterday.’

The door closed and they were left staring at each other.

‘Sir, I arrived early for my appointment …’

‘Did you now?’

‘I did knock.’

‘Good. Good. Thought I heard something.’

Disconcerted by the fresh-faced, soap-scented presence, Joe went to open another window. That done, he began to pace about in a distracted manner.

‘Sorry to have kept you waiting, Miss Wentworth. We’re running a bit late today. Look here … I’ll get straight to it.’ He began to speak in her general direction. ‘You may have heard … no, how could you? Anyway – there was something of a bloodbath last night in the West End. Admiral shot to death on his doorstep, butler wounded, beat bobby left for dead like a dog in the road, London cabby fighting for his life in hospital,’ he confided in a rush. ‘Carnage on the streets, I’m afraid. You’ll read all about it in the papers, no doubt. It’s just what those hyenas have been waiting for. I’ve been … um …’ he glanced at the telephone sitting in the middle of his desk, ‘involving myself. Rather emphatically. Hard to stand back when one of the victims was a man I counted as my friend. And a friend avowedly under my protection at the time.’

He stopped his pacing and added bitterly: ‘There will be many to ascribe responsibility for the whole shambles to me. Not least myself.’

His flood of alarming information seemed to have rendered the girl speechless. Well, how else might he expect a young policewoman to respond to a throbbing monologue from her superior but with a wise silence? Finally she managed to say softly: ‘I’m so sorry you’ve lost your friend, sir. You must be very distressed. And you must want to be left alone to get on. Would you like me to go away for now? I can come back some other time.’ She took a step back towards the door.

He held up a staying hand. ‘No, don’t go. I shall mourn the admiral later and in my own way. Which is to say with targeted vigour.’ He shot a glance of such deadly intent in her direction that Lily looked aside. ‘Now you’re here, come on over and let’s renew our acquaintance.’

She approached the desk, ignored the chair set in front of it and stood to attention as she’d been trained. Feet a precise eighteen inches apart, straight back, shoulders down, palms to the rear. All very correct. To salute or not to salute? Joe realized she was questioning the protocol. She hesitated for a moment, then, apparently deciding he merited the gesture, gave him a perfect salute.

He managed a grin. ‘Returning mine of the fourteenth, I take it? Thank you. Do sit down and we’ll start again.’

Puzzlingly, the girl stayed on her feet.

Wrong footed by her silence and rigid stance, Joe re-launched the conversation in a welcoming and very English prattle.

‘Looks as though it’s going to be hot again today.’

‘We’ve had the hottest summer for twenty-seven years, I understand, sir.’

‘Yes … When will it end? Pigs keeling over with heat stroke at the county show …’ he offered with a bland smile.

‘Reckless swimmers getting into difficulties in the Serpentine.’

‘But there’s some good news. We have our Prince of Wales back home safe and sound at last.’

Her voice was tight with strain as she returned yet another answer in this tedious sequence. ‘After eight months touring India, he will be acclimatized to this heat.’

‘Well, that’ll do for our review of the papers,’ Joe said, and fell silent.

In pursuit of his brief he began to pace about the room again, noting for the record, in what he hoped was an unobtrusive fashion, her height, weight and general deportment. He was relieved to see he’d remembered correctly the trim figure, the modest height. He couldn’t be sure about the face. With the downcast eyes and the large-brimmed hat, she could have been anybody.

A closer inspection was now essential. He went to perch on the front edge of his desk, eyes on a level with hers, improperly close. This overbearing male behaviour was calculated to disturb, to test the subject’s mettle. It was a crude ploy he’d had much success with in the interrogation of male prisoners, military and civilian. The scar skewed his face and Joe had learned to use the sardonic twist with its suggestion of pain survived to intimidate his subjects. He’d noticed that even the tough nuts were unable to hold his eye. Their gaze faltered and slid to one side. They began to fidget and tell him their lies with less confidence.

If the girl ran whimpering from the room or kicked him in the shins at this point, he wouldn’t blame her but that would have to be the end of it.

She responded by staring calmly at a spot on his tie, a slight twist of disdain on her lips.

Perfect.

‘Now then, Miss Wentworth … er, Lilian? That your given name?’

‘I’m usually called just Lily, sir. By those who know me. “Constable” by those who don’t.’

His scrutiny had been over close and over long. And perhaps it was unfair to expose her to blood-spatter and bristle at this hour of the morning. When she caught him inspecting her feet he muttered: ‘Those boots are a disgrace. Not your fault. Poor quality leather. Won’t take a polish. The men wouldn’t put up with them for two minutes. I’ll have a word in the right ear.’

‘It will go straight out through the left, I’m sure, but thank you for the thought, sir.’

Was the tone rebellious? Joe frowned. Not yet. Just this side of acceptable. He’d push her further. He peered playfully under her brim, questioning. She went on looking straight ahead, impassive.

‘Why don’t you sit down? I don’t want to conduct this interview standing. We may be here some time.’

She sank uneasily on to a chair.

‘You’re smaller than I remembered,’ he remarked.

‘Tall enough to satisfy the height requirement.’

Joe picked up a pencil and scratched a note for himself: 5′6″?

‘And younger.’

‘I lied about my age. Sir.’

A swift glance into the unblinking, innocent eyes told him she was certainly lying now. Personal details of recruits were meticulously checked. Joe knew when he was being needled. He wrote again, taking his time: 26, could pass for 18. Insubordinate?

‘And your weight, miss? You would appear to be … er … not exactly well covered in the flesh department.’

He’d clearly touched a nerve at last. The nostrils flared and her voice when she replied was glacial: ‘After eight years of privation, sir, are we surprised? There’s been a war on.’

He scribbled: Skinny. Insubordinate! ‘Look – remove your hat, will you?’

She took off her hat and placed it on her lap.

Joe stared at her hair in surprise. ‘Always interesting to see what you’re hiding under those domes. Glad to see it’s just a dolly-mop of hair and not a bomb.’ He glanced again at her thick bob and scribbled a note on a pad. ‘Tell me – again for the record – how would you describe the colour of your hair? Blonde?’

‘Say straw, sir. If it could possibly be of any interest to anyone.’

Joe thought Miss Wentworth’s shining flaxen hair would interest any man. He busied himself for an annoying moment or two, unconvincingly jotting a further note: Hair – fair, fashionably cut. Brows and lashes darker. Green? eyes. V. pretty … and cut himself short.

He was making a pig’s ear of this.

Should he have delegated the unwelcome task to his super? To his Branch man? Joe reassured himself by remembering both men’s lack of experience with the fair sex and their declared antagonism to the Working Woman. No, neither officer could have gone one round with this sample. He was becoming increasingly certain his choice was a good one. He just had to make the right approaches.

He settled back in his chair, trying for friendly and approachable. ‘Now, before I tell you why you’re here …’ he indicated the file with her number on the cover, ‘I’d like to congratulate you on your prompt and decisive action at the station. I’ve entered a commendation on your file. Would you like me to read it out for you?’