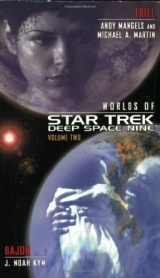

Текст книги "Trill and Bajor "

Автор книги: Andy Mangels

Соавторы: J. Kim,Michael Martin

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

“Rena!” Jacob shouted.

She almost didn’t see the collapsed bank in time to stop her from running off the ledge. Only Jacob, who had approached this last stretch before the Yolja with more caution than she had, had seen how the ground where the bridge joined the land had given way. As she stuttered to a halt, she tripped over a fallen tree branch and fell forward onto her face. The force of her fall split open her knapsack, spilling the contents, including her precious sketchbook, into a muddy puddle.

Her sketchbook. The only part of her university life she’d brought home with her. Her canvases, her paintings—all of them had remained behind in the student studio when she left school to return to Mylea. She left believing she would never see those artworks again, that symbolically, she needed to leave them behind if she were to truly embrace the path she was destined for. The only memory she allowed herself to keep was her sketchbook. Now she watched the dirty water soak the pages through, irrevocably destroying months of charcoal, pastel, and pencil memories. She beat her fists against the ground, teeth clenched. Though she felt that remaining in her prostrate position fit her circumstances, she pushed herself up onto her elbows, pulled her legs up into a kneeling position, finally righting herself by the time Jacob reached her. Tersely, she brushed aside his offers of assistance, ignoring the smarting cuts and bruises on her knees and forearms as she paced.

Cursing, she screamed at the sky, screaming as if she believed that the Prophets themselves could hear her, demandingthey hear her. “I’m doing what you asked! I walked away from my life to follow the path laid out for me! Do you hear me?”She stamped her foot angrily, her hands balled into fists. “If I am submitting to all the demands placed on me—all of them!—why can’t you make it easier? Do you hear me, dammit?! Answer me! Send your Emissary or your Tears, but answer me!” Rena continued screaming her diatribe until she was hoarse, her throat sore from exertion. The storm’s tempo picked up, and soon she was soaked through.

Throughout her display of temper, Jacob had stood off to the side, leaning against a road marker and respectfully averting his eyes from Rena. Abruptly, he took a few long steps forward, pointing at the river. “There’s something out there—I can see the light on the bow.”

“They’ll never see us through this storm,” Rena said, coughing. Heavy with discouragement, miserable from cold, she could see no way out of their predicament; she plopped to the ground, prepared to spend the night in the downpour.

Not to be dissuaded by her negativity, Jacob unfastened a pocket on his gear bag, fished around, and removed a wristband with a small circular object mounted on top where a chrono face would be. He thumbed a switch and a brilliant light beam burst out of the side. Holding the light before him like a signal beacon, he ran down as close as he could to the riverbank, trying to draw the attention of the boat. Minutes passed. Then: “It’s changing course! Rena! You can go home!” He let loose a loud whoop of joy.

In spite of all that had gone wrong, Rena couldn’t help smiling. Steward, indeed.

Girani

As she marched toward the examination room, Dr. Girani Semna suspected that one thing she wouldn’t miss about working in Deep Space 9’s infirmary was all the Cardassian instrumentality. Most of the medical staff had grown accustomed to it over the years, herself included. Her patients—the Bajorans, particularly—were another matter. They tended to become uncomfortable in this place, beyond their natural aversion to going to see a doctor at all. Despite the fact that the entire station shared the same design elements and seemed no longer to trouble most of the residents, the infirmary made them particularly uneasy. All things considered, that was no surprise. This was, after all, where they felt the most vulnerable.

Her newest patient, she suspected, was going to be no exception.

“Commander Vaughn,” she said as she entered the exam room. “What an unexpected pleasure this is. How nice of you to drop by.”

Keeping his arms tightly folded over his exam tunic, Vaughn said, “Spare me the sarcasm, if you please, Doctor, and let’s get this over with. I have duties awaiting me.”

Girani snorted as she prepped a mobile standing console near the biobed. “Now, Commander, you’re not suggesting yourduties should interfere with the execution of mine, are you?”

Vaughn smiled at her appreciatively, and she knew she’d scored a hit. “Where would you like to begin?”

“The usual way. Just lie back on the biobed and breathe normally while the medical scanners take a read.”

Vaughn complied. Girani keyed the exam program to commence, and the ceiling-mounted diagnostic array hummed to life. A narrow stripe of blue light slowly crept back and forth over Vaughn’s body. While he lay staring up at the array, he said, “I understand you’re leaving us.”

“That’s right.”

“If it isn’t too forward of me…may I ask why?”

Girani shrugged. “I’ve been thinking about it for some time. And with the station becoming all-Starfleet, it seemed like a good time to make a clean break.”

“Have you considered staying aboard—joining Starfleet?” Vaughn asked. “I know you’ve been an asset to the station since before I joined the crew. Everyone here thinks very highly of you, especially Dr. Bashir. Your application would likely sail through.”

Girani blinked. This was the last thing she expected. “That’s kind of you to say, Commander,” she told him.

“Is it something you’d be open to?”

Girani hesitated. “I hope you won’t take this the wrong way…but joining Starfleet simply doesn’t interest me. I find my service in the Militia very fulfilling, and I want to continue it. I can still do that on Bajor. Besides, with so many of my people switching over as it is, the Militia needs experienced officers now more than ever.”

A frown crossed the commander’s features. “Does it concern you? The migration of so many Militia personnel?”

“Concern me?” Girani shook her head. “No, it’s the logical evolution of Bajor’s relationship to the Federation. It only stands to reason that some Bajorans will welcome the opportunity to serve in Starfleet, while others choose to stay with the home guard. Both are important to Bajor, after all.”

Vaughn seemed to appreciate hearing her take on the subject. She wondered if he was encountering some bitterness about the changeover down on the planet.

Girani began to check the current scans against Vaughn’s medical file, displayed on a nearby monitor. “Oh, before I forget…happy birthday, Commander.”

Vaughn closed his eyes, leading Girani to suspect the topic was unwelcome. Oh, well….

“Thank you,” he said quietly. “But I think it’s only fair to tell you that I stopped celebrating my birthday about forty years ago.”

“Really?” Girani said, genuinely surprised. “That seems like a waste. Not even your hundredth?”

Vaughn shrugged. “It’s just a number. Besides, where I was that day, another birthday was the last thing on my mind.”

Girani decided not to pursue the matter. A few minutes later, the medical scanners emitted a low chime signaling that their sweep of Vaughn’s body was complete. “Good. Now sit up and strip to the waist, please.”

“Is this really necessary? The scanners—”

“Every doctor has her own unique style, Commander. This is mine. I’ll study the results of the master scan later. Now kindly shed your tunic and face away from me, please.”

After a moment’s hesitation, Vaughn did as instructed, shrugging out of the exam tunic and baring his back for Girani. Holding an active medical tricorder in one hand, she used the other to examine Vaughn’s upper body directly. Her attention shifted back and forth from the display to her patient: some scarring all across Vaughn’s back that had obviously never been subjected to a dermal regenerator; a few areas of increased epidermal pigmentation associated with the elderly—what humans called senile lentigines, or “liver spots.” There was also some settling of muscle tone.

She found a large bruise on his left side, over the rib cage. He flinched when she touched it. The tricorder revealed a hairline fracture.

“You’re showing another two percent decrease in bone density.”

Vaughn’s response was immediate: “I’ve been on a regimen of Ostenex-D for the last twelve years.”

Girani sighed. “Ostenex doesn’t prevent your bones from becoming brittle, Commander. It only slows the process down. And after a while, it stops working for some people.”

Silence. According to her tricorder, Vaughn’s heart rate was spiking, but his voice remained even as he asked, “Can you prescribe something else?”

Girani hesitated. “There’s a newer version of the drug you might try, but I can’t promise you it’ll work any better.” She reached for her osteo-regenerator, switched it on, and pressed it gently against Vaughn’s ribs for several minutes. When at last it beeped, signalling that the bone had been mended, Girani put the device away and resumed her tricorder scan.

Girani then noticed a raised line of flesh that started on the side of the commander’s neck and disappeared into the white hair behind his left ear. With his uniform on, she realized, it would hardly be noticeable at all. Upon close examination, however, it was quite obviously the telltale sign of an old and serious injury. “Where’d you get this scar?”

“Back home,” Vaughn answered, shrugging. “When I was a kid.”

Girani held the tricorder up to the scar. “There are traces of foreign DNA under the skin, but I’m not finding a match in the medical database.”

“Expand the search to include class-Q life-forms,” Vaughn suggested, “and you’ll find it belongs to the species Draco berengarius.”

Girani’s eyebrows shot up at that. “The original wound was quite deep, though,” she said, noting that her tricorder was showing a re-fused skull and indications of slight damage to the left hemisphere of the brain. “It looks to me as if you were lucky to have survived. You’ve never experienced any side effects?”

“No.”

Strange as the wound was, if Vaughn had gone this long without suffering any ill effects from it, it was unlikely to make any difference now. Girani redirected her tricorder at Vaughn’s heart. “How often do you exercise?”

“I go swimming for half an hour every morning before my shift. And before you ask, yes, I’m watching my diet.”

“According to your medical file, you had a cardiac episode six years ago.”

“A mild one. Nothing since.”

“What about your energy level?”

Vaughn didn’t answer.

“Commander? I said—”

“I get tired more quickly these days,” Vaughn snapped. “I’m a little slower getting up in the morning. Are you satisfied, Doctor?”

Unfazed, Girani said, “That depends. Are you experiencing any other symptoms Starfleet should know about?”

That’s when he turned and looked at her directly. “I’m old,Doctor. And I’m getting older all the time. Starfleet knows that. Putting a microscope on every creaking bone, every aching muscle, won’t tell them anything they aren’t already aware of.”

“And that means what, exactly? I should simply give you a clean bill of health?”

Vaughn’s eyes narrowed. “Is there any reason you wouldn’t?”

Girani set down the tricorder and came around the biobed to face Vaughn directly. She pulled up a chair and straddled it. “Commander, you’re a hundred and two years old. You’re more than two-thirds of the way to the end of your natural life, and while you’re in good health for a human male of your years, it’s still an age when most of your kind has retired.”

“If you check, you’ll see that many centenarian humans are still on active duty in Starfleet.”

“But few of them are in the field,” Girani countered, “and with good reason. Medical science and proper self-maintenance may have lengthened the human life span over what it was a few hundred years ago, but as you yourself clearly stated, you haven’t stoppedaging.”

“Come to the point, Doctor.”

Girani sighed. “Don’t misunderstand me, Commander. All things considered, your health is excellent. But at some point, perhaps sooner than you imagine, you’ll have to face the end of your ability to continue serving in your current capacity.

“But I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know, am I? You’ve already had this conversation with Dr. Bashir.”

Vaughn scowled and looked away for a moment, then turned back to her. “Is it your medical opinion that I’m unfit for duty, or that my current health is a liability to this crew?”

“No, but—”

“Then we’re done here.” Vaughn pushed off the biobed and reached for his gray tank and red uniform shirt, folded neatly nearby atop his jacket and trousers.

Girani stood up and shook her head. “Julian warned me you were an impossible patient.”

“Did he, now?” Vaughn said as he dressed.

“Yes. And I feel no reluctance agreeing with that assessment,” Girani said with rising anger. “For someone of your life experience, I expected a little more wisdom.”

Vaughn slammed his hand on the biobed. His emotions were palpable, but he succeeded in reining them in quickly. Nevertheless, Girani was sorely tempted to recheck his blood pressure.

Finally he said, “I apologize. Doctor. It’s just—” He stopped, struggling for the right words. “I’m simply not ready to give up this life yet.”

The forcefulness—or was it desperation?—in Vaughn’s voice surprised Girani. She remembered a lot of aging resistance fighters who’d expressed similar sentiments when advised to slow down. During the Occupation, it was difficult to argue that anyone should scale back their efforts to help free Bajor from Cardassian control. The Federation, however, wasn’t at war anymore. So what cause was driving Vaughn?

“This issue will not go away simply because you choose to ignore it, Commander,” Girani said gently. “You need to face the fact that the time is coming, whether you like it or not, when you will have to stand down. My hope for you is that you’ll recognize it yourself when it becomes necessary. Otherwise, someone willmake that decision for you, and I suspect you’re the type who would find such a thing undignified, even humiliating. I doubt that’s how you’d want your career to end.”

Vaughn stared vacantly into the middle distance. “No. I can’t say it is.” His gaze refocused, and he looked at her. “Thank you, Doctor. Your candor is sobering. You’ve given me a great deal to think about. Are you sure you can’t be persuaded to join Starfleet?”

Girani laughed. “After the conversation we just had, you still want me to sign on?”

“Yes,” Vaughn said simply. “Integrity, directness, and persistence are qualities that shouldn’t go unappreciated.”

Girani’s smile was genuine. “Thank you, Commander. Truly. But getting back dirtside is what I really want. And besides,” she went on, seeing the dead face of First Minister Shakaar, “there are things about my time here I want to forget.”

Vaughn nodded, accepting her answer. “Just know, then, that you’ll be missed. By all of us.”

“Thank you,” Girani said again.

Vaughn finished dressing while Girani moved to an interface console and uploaded her tricorder’s readings to the infirmary mainframe, to cross-check later against the master scan taken by the diagnostic array. She was changing Vaughn’s prescription to Ostenex-E when she heard a voice call out, “There you are, Commander! I heard I might find you in here.”

Girani turned. Standing in the doorway was Quark, his hands held uncharacteristically behind his back. Girani was about to deliver a scathing reprimand about a patient’s right to privacy in coming to see a physician, but Vaughn spoke first.

“Mr. Ambassador,” he said, pulling his uniform jacket on. “What a pleasure it is to see you.”

Girani suppressed a laugh. Quark’s diplomatic appointment as Ferenginar’s official representative to Bajor was still hard to take seriously, especially after it became common knowledge that it had come about purely as an act of nepotism on the part of Grand Nagus Rom, Quark’s brother.

Quark snorted at the commander’s greeting. “Ah, you say that, but you don’t mean it.”

Vaughn looked at him. “How could you tell?”

“I’m willing to overlook your insincerity, Commander, given your situation and all.” From her angle, it appeared to Girani that Quark was holding something behind his back, but she couldn’t make out what it was.

“My situation?” Vaughn asked.

“Another birthday,” Quark said. Vaughn shot a look at Girani, who shrugged, putting on a face with which she hoped to project, Don’t look at me, I didn’t tell him.“At your age, that’s gotta make anybody cranky,” Quark went on. “It can’t be getting any easier. You’re less steady on your feet, less quick with a phaser, less able to remember things, less able to endure the, ah, company of females…”

“Less able to endure the company of you,” Vaughn added.

“Commander, please,” Quark said. “Let’s not spoil what should be an occasion to celebrate.”

Vaughn stared at him. “You’re here to help me celebrate.”

“Well, as it happens, I was at the station’s florist signing for a shipment of Kaferian lilies, just as Mr. Modo was processing an order—intended for you. Imagine my delight when I learned it was a birthday present from someone on Bajor. As a good citizen, not to mention the senior Ferengi diplomat in residence, I volunteered to bring it to you personally.”

“Is that right,” Vaughn said, as Quark’s other hand emerged, holding a narrow cone of festive paper wrapped around a single, long-stemmed flower. There was a note card attached, and an isolinear rod taped next to it. The flower, Girani saw, was an esaniblossom.

Vaughn thanked Quark as he took the gift, unsealed the note card, and smiled faintly when he read the contents. Quark’s futile attempt to inconspicuously lean over far enough to read the note told Girani that at least he hadn’t scanned the message before bringing it to the commander.

Vaughn refolded the note and detached the isolinear rod from the giftwrap. “What’s this?”

“Compliments of the Ferengi Embassy,” Quark said.

“You mean the bar.”

“Just present it to any member of my staff to receive an hour of holosuite time at our special birthday discount. And two free drinks.”

Vaughn raised an eyebrow. “Top shelf?”

Quark laughed. “That’s a good one. I’ll have to remember that. Oh, I almost forgot to mention: For a small fee, you can get an official proclamation from the Ferengi Alliance declaring this Elias Vaughn Day. It comes with a certificate.”

“Pass.”

“A smaller fee will get you an official birthday greeting from the Grand Nagus.”

“You’re enjoying your diplomatic appointment far too much, do you realize that?”

“Take joy from profit, and profit from joy. Rule of Acquisition Number Fifty-five.”

“My mistake,” Vaughn said. “But I’ll have to pass on that offer as well, I’m afraid.”

Quark made a disgusted noise and shook his head. “No offense, Commander, but your people have no idea how to celebrate a birthday properly.”

Vaughn shrugged. “We’re only human.”

“My point exactly. Would it kill you to spend a little more time in my bar?”

“Don’t you mean ‘embassy’?”

“Quark’s is a full-service establishment,” the ambassador said. “I’m just trying to reinforce that fact among the station populace.”

“And you think having the station’s second-in-command decide to celebrate his birthday there will encourage others to do the same,” Vaughn guessed.

Quark spread his hands. “Well, after all, every day is somebody’sbirthday.”

“True enough,” the commander conceded, raising the esaniflower to his nose and gently breathing in its fragrance. “As it happens, though, I have a prior commitment this evening. Some other time, perhaps. Thanks for the gift.” He gave Quark’s shoulder a friendly pat, and nodded to Girani as he strode out of the exam room. “Doctor.”

As Vaughn exited, Quark seemed to notice Girani for the first time, a new gleam forming in his eye. “Doctor! When’s your birthday?”

Hovath

Hovath awoke to darkness and the taste of blood. Pain nested behind his eyes, its sharp black beak stabbing his brain. His lower lip was numb and felt twice its usual size. His face was sore, and cold on one side. Through his cheek he felt a low vibration, one he recognized: the deckplate of a spacecraft at warp.

Light assailed him through his eyelids, an instant before his mind registered the sound of a switch being thrown, the echo reverberating off metal walls.

“Up,” a harsh voice demanded, just as he felt rough hands grab hold of his vestments and force him into a hard chair. Hovath struggled to open his eyes against the glare, saw that he was sitting at one end of a plain metal table in the midst of an otherwise dark room, a light on the other side shining directly into his face. The stabbing pain behind his eyes grew worse.

Then it all came back to him.

Shards of memory broke through the fog: alien faces, the heat of the explosion, the light of the village burning, screams of agony, the scent of death.

“Iniri!”The wail of grief tore itself from the rawness of his throat, sending him into a fit of dry, painful coughing.

I’m alive. Why am I alive?The crushing knowledge of what had befallen his people was proof that he wasn’t dead…unless death was not the thing his faith maintained. Though the concept of an afterlife defined by eternal loss and regret was alien to Bajoran thinking, Hovath knew it was powerful idea in human mythology. They had names for it. He knew one of them: hell.

“Ke Hovath,” another voice said, softer than the first, female. But not his wife’s. Iniri!

Then a different horror seized him: They knew his name! Prophets help him, they knew his name! They had killed everyone, his friends and neighbors, his family, they had burned the village to the ground—but they had taken him, kept him alive. They wanted him!

“Why?” Hovath found the strength to ask before another coughing spasm took hold.

“Let him drink,” the woman said. A second later, a sipstick touched his lips. Cool water flowed over his dry, leathery tongue, bringing some relief from the choking taste of ash. He began to drink greedily, becoming aware of two figures on his right and left, standing over him.

“That’s enough,” the voice said, and the sipstick withdrew.

Hovath looked up, squinting against the light, attempting to see the speaker through the glare. The most he could discern was a dark shape sitting on the opposite end of the table. “What do you want of me?”

“The same thing you want. Answers,” his captor said.

“I won’t help you.”

“I think you will.” The dark figure seemed to turn slightly to one of her henchmen. “Show him.”

The underling on his right—Hovath thought dully he might be a Nausicaan, though he was uncertain—moved to the nearest wall, where a viewscreen was set up. The alien activated it, and Hovath’s heart lifted.

Iniri was alive. She was slumped in the corner of a small room, her red-blond hair in dissaray, her clothing singed. She had her arms wrapped around herself and she appeared to be weeping. She looked as if she’d been beaten, and Hovath’s moment of relief turned to rage.

Then he felt the blood drain from his face as he recognized her surroundings. An airlock.

“As you can see, your wife lives. For the moment,” the woman said. “If you wish her to stay that way, I require your full cooperation.”

“Please,” Hovath moaned. “Let her go.”

“No. Not until you give me what I need. Otherwise Iniri dies.”

Hovath squeezed his eyes shut and clenched his hands into fists on top of the table, his mind searching for a way out of his nightmare. His teeth bit into his swollen lower lip until he tasted blood again.

“How can I possibly help you? I’m no one.”

“Oh, but that is hardly true.” the woman said. “Until this very morning you were the sirahof Sidau village. But that’s not all, is it, Hovath? You’ve also spent half of each of the last six years as a student in Musilla University, where you pursued what can only be described as an atypical course of study for someone of your upbringing, and published a rather remarkable document.”

From the far end of table, something slid toward him across the surface. His fingers caught it. A padd, but not of a design he’d ever seen before. Its little screen displayed the title, Speculations on the Architecture of the Celestial Temple.

His name appeared directly below it.

“I’ve become quite familiar with your work,” his captor said.

Tears streamed from Hovath’s eyes as he began to understand why all this was happening.

Hovath’s spirit had always been restless, distracted; it was for that very reason, he recalled, that the old sirahhad pushed Hovath so hard before his death, seven years ago. Hovath had stumbled during his first attempt to control the Dal’Rok.The old sirahhad felt Hovath’s pagh,and found him wanting. Enlisting the aid of two humans from the space station, he crafted a lesson whereby Hovath learned to commit fully to the duty for which he had been trained his whole life.

As the new sirah,Hovath served his people well. But the villagers needed his services as storyteller only for a span of five days each year. The rest of that time he was merely a scholar and sometime spiritual guide. Though he had mastered his role, his spirit remained restless, his mind thirsty for knowledge that had no place in the village. A year after he became the storyteller of Sidau, he announced his intent to spend Hedrikspool’s autumn and winter months each year in secluded study, away from the village. No one, not even his new bride, Iniri, had known where he went, or the controversial nature of his work: a single line of theological and scientific inquiry that had been circling round and round in his mind since the Emissary had first come to Bajor.

From the day of its discovery, the wormhole had excited him, captured his imagination. For the Celestial Temple to manifest itself in such a manner, it could only mean that the Prophets sought to be understood in ways apart from the wisdom of the prophecies. Or so Hovath believed. Come,he felt the Temple beckon. See what I am.

After the death of the old sirah,Hovath’s life walked two paths. On one he was the faithful storyteller of the village, Keeper of the Paghvaramand Foe of the Dal’Rok.On the other path he’d become a contemplator of Their Manifestation, seeker of secular truth, and student of the architecture of the Temple. He had believed that these two paths, while seeming separate and parallel, would in time converge into a single path of Truth on which he could guide his flock in Sidau, and perhaps others, toward a new enlightenment.

Now a different Truth was upon him, and it stood revealed as his own folly and arrogance.

He shook his head and pushed the padd away. “This is nothing.”

“I very much disagree,” the woman said. “I find it quite compelling. Your imaginative approach to theoretical physics is not merely unexpected, but inspired. You believe the wormhole is not what it seems to be.”

“No,” Hovath said tightly. “I believe it is morethan it seems to be.”

“Explain.”

Hovath brought his fist down on the table. “If you’ve read my work, you already know the explanation.”

“Indulge me.”

Hovath said nothing.

His captor addressed the Nausicaan, who still stood next to the screen showing the image of Iniri. “Space her.”