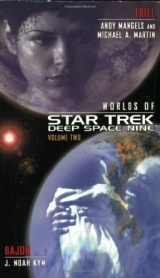

Текст книги "Trill and Bajor "

Автор книги: Andy Mangels

Соавторы: J. Kim,Michael Martin

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

He laid a hand on her arm, gently preventing her from getting to her feet. “DS9 is less than half a day away. I wanted to talk to you before we get back and end up getting swept into yet another crisis.”

She nodded. “You want to talk about the mission?” As reticent as she still obviously was about rehashing her world’s history with him, Bashir thought she was hoping she wouldn’t have to discuss anything else.

“Only peripherally. It’s really about, ah, the way you handled certain aspects of the mission.”

She leaned back in her chair, crossing her arms in front of her in a classic display of defensiveness. Her dazzling blue eyes narrowed. “Trill was attacked by a clandestine global terror network, Julian. Under the circumstances, it seems to me that the mission was as successful as anybody could have hoped.”

“I can’t argue with that, at least in retrospect.” Feeling she was beginning to tie him in knots, he decided he’d better simply come out with his point. “But I think you may have been a bit…high-handed when you went off to Mak’ala.”

Judging from the puzzled look on her face, he might have just sprouted a second head. “ ‘High-handed,’ ” she repeated.

“When I tried to point out that it was a risky thing to do, you simply brushed me off.”

“Going diving at Mak’ala wasrisky, Julian. You didn’t have to tell me that. But it turned out to be the right thing to do.”

He nodded. “Yes, but only in retrospect. At the time, it was as though you had no regard whatsoever for my input.”

It was her turn to nod. “Ah. So this isn’t really about the mission. It’s about your evaluation of my command style.”

His frustration finally boiling over, he rose from his chair and stepped to the rear of the cockpit before turning once again to face her. “Dammit, Ezri! Don’t trivialize this! I’m not trying to defend my delicate ego. Each of us took wholly opposite approaches to the crisis. Doesn’t that bother you?”

“Not especially, Julian. It was my call, and I made it.” She paused thoughtfully for a moment before continuing. “And maybe that’swhat’s really bothering you—that I’ve stepped into a role you’re not comfortable with.”

“That’s not true,” he said, waving his hands dismissively. “I’ve always supported your decision to switch over to a command-track career.”

“Even though it came as a bit of a shock, at least at first.”

He felt a small smile tug at the corners of his mouth. “I prefer to think of it as a surprise, and Daxes are nothing if not surprising. But again, this isn’t about your becoming a command officer.”

Ezri, however, wasn’t smiling. “Then is it about me being yourcommanding officer on this particular mission?”

“Ezri, you were above me in the Defiant’s chain of command all those weeks we spent exploring the Gamma Quadrant. That wasn’t a problem for me then, and it isn’t now.”

She sighed wearily. “Then what exactly isthis about, Julian?”

As he paused for a moment to compose his thoughts, he began to realize how difficult a question she had posed. “It’s about whether or not my expertise is important to you. My judgment. My advice. My experience, even though I admit I don’t have a backlog of eight other lifetimes of memories to tap into.” He hesitated a beat before plunging on to the real crux of his complaint. “It’s about whether or not I’mimportant to you.”

All of the exasperation abruptly drained from her face, and she looked stricken. “And you think you’ve become less important to me since I started wearing this red collar.”

His response was nearly a whisper. “It seems that way, yes. At least sometimes.”

She rose from her chair, put her arms around him, and buried her face in his shoulder. He returned the embrace, which seemed fueled more by regret than by passion.

They stood that way for a long time, in silence, while the runabout’s autopilot carried them inexorably homeward.

“Jadzia,” Ezri said finally, her head lying against his chest.

He partially disengaged himself from the embrace so that he could see her face. Unshed tears stood in her wide, cerulean eyes.

“Sorry?” he said.

She finished dismantling their embrace, then resumed her place in the pilot’s seat. She stared straight ahead at the shifting star field as she spoke. “You were in love with Jadzia.”

“I don’t really see what that has to do with anything,” Bashir said, feeling defensive in spite of himself.

“You loved her,” she repeated, turning to face him. “You don’t have to be embarrassed to talk to me about it. Worf may have arranged a place in Sto-Vo-Korfor her, but she’s still right here.” She placed a hand on her abdomen, where the Dax symbiont stored the memories of all its previous hosts.

And she’s in my heart as well,he thought. And always will be.He slumped into the seat next to Ezri’s, knowing he was beaten.

“All right. I didlove Jadzia. What of it?”

“You were in love with her, but you lost her to Worf before you could do anything about it. And you lost her again when she died. Then Ezri Dax blundered into your life. Suddenly, you had a second chance at Jadzia. And now, here we are.”

“I love you,Ezri. Not Jadzia’s ghost. Don’t you believe that?”

She nodded, the tears in her eyes sparkling like distant quasars. “I do believe you, Julian. But I’ve always wondered if the only reason for that is because you loved Jadzia first.”

He was feeling adrift; when he’d decided to air his grievances with her, the last thing he’d expected was for her to reciprocate. “What’s your point, Ezri?”

“My point is that we came together under some pretty strange circumstances. There was the emotional baggage you had with Jadzia. The Dominion War. The final battle for Cardassia. We became a couple not knowing whether we’d even survive the first day.” Tears began painting wide stripes down both her cheeks.

All at once he saw precisely where she was heading. And he was more than a little surprised when he realized that she was making perfect, if painful, sense.

“And none of that bodes well for a stable relationship,” he said quietly. He suddenly noticed that his own cheeks were damp as well.

“It isn’t that you’re not important to me, Julian,” she said. “You’re a dear, sweet, man. A goodman. But the part of me that’s just plain old Ezri wonders if we’d have been drawn together at all if I didn’t see you through Jadzia’s eyes…or if you didn’t see her in mine.”

He opened his mouth to protest, then stopped himself. Was it egotistical to acknowledge that he might not have developed feelings for Ezri if not for her symbiosis with the renowned polymath Dax symbiont—and the link to his beloved, dead Jadzia that had come with it?

“I suppose we’ve both changed quite a bit over the past year,” he said finally, knowing that his words communicated little of value even as he said them.

“Me especially,” she said, gracefully permitting his obvious dodge as she chuckled through her tears. “And now we’re two very different people.”

We’ve matured together,he thought. I don’t think we could have had this conversation just a few months ago. At least not without a good deal more shouting.

They sat together in silence, watching the stars. Holding hands.

“I suppose we’re done now,” he said at length. “As a couple, I mean.”

They faced each other. He studied her eyes, just as she was clearly studying his. The truth now stood revealed as obvious.

“I hope you don’t mind my telling you that I still love you,” he said, fixing his eyes back on the interstellar void ahead. “I think I always will.”

Her fingers felt cold against his as she squeezed his hand. “And I’ll always love you, too, Julian.” A brief sidewise glance told him that her gaze now faced front as well.

Very gently, he released her hand. She withdrew it. Whatever cord had connected them romantically seemed to snap with that gesture. They were friends now. Dear friends, and colleagues.

The Rio Grandecontinued hurtling homeward, mere hours away from Deep Space 9. And though Ezri remained seated beside him, the blackness of space seemed not nearly so deep and cold as the gulf that now yawned between them.

Bajor

Fragments and Omens

J. Noah Kym

About the Author

J. Noah Kym has been characterized by his friends as a tough nut to crack.

For Mom

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, deepest gratitude to Paula Block for her support, her enthusiasm, and her suggestion of this story’s villain.

Muchas graciasalso to Heather Jarman and Jeff Lang, scribes extraordinaire, whose help and inspiration were invaluable to the crafting of this tale.

A big shout out to all the folks who make Star Trek,on screen and in print, for all the worlds and characters they continue to create.

Finally, a tip of the hat to my editor, Marco Palmieri, for inviting me to explore the world of Bajor.

Historian’s Note

Chapters 1, 2, 11, and all the “Rena” portions of this tale unfold over the three weeks immediately following the Star Trek: Deep Space Ninenovel Unity.The rest of the story transpires during a single day at the end of that period, in late October, 2376 (Old Calendar).

There is no such thing as an omen. Destiny does not send us heralds. She is too wise or too cruel for that.

–OSCAR WILDE

The whole world is an omen and a sign.

–RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Sisko

Eyes closed, Benjamin Sisko listened to his wife’s slow, steady breathing. Inhaling deeply, he began a mental list of the smells: lemon-scented laundry soap, Kasidy’s face cream, mother’s milk, baby powder. Oh, my,he thought, but that takes me back. How many years?Jake was—twenty-one? Could that be right? And I thought I’d left baby powder far, far behind me.

Only a meter from Kasidy’s side of the bed he heard a faint stirring no louder than a mouse kicking in its sleep. In response, under his arm, Sisko felt Kasidy’s arm spasm and she mumbled something low and unintelligible. “Don’t worry,” Sisko murmured, eyes still shut. “I’ll get her.”

He opened his eyes and watched the blades of the ceiling fan churn the early-morning air. Kasidy had installed the fans shortly after she’d moved into the house, one of the many changes she had made to his original design that made their home seem as wonderfully strange as it was familiar. After the years upon years he’d spent in perfectly modulated environments on starships and starbases (and the even less perfectly modulated spaces of Deep Space 9), a ceiling fan seemed a delightfully anachronistic detail. What a wonderful idea.He was glad Kasidy had thought of it.

The mouse in the tiny crib stirred again, sighed, and made a wet sound. Lifting his head, Sisko, the Old Campaigner, the Experienced Dad, sniffed, then drew a breath and held it. Ah, yes, I remember this, too.

The tiny creature in the crib voiced her displeasure with the recent change in her comfort level. Kasidy’s head rose minutely. “Sorry, love,” he said, rolling out of bed. “I’m going.”

“She’s going to be hungry,” Kasidy muttered into her pillow.

“Of course she is,” Sisko said as he reached into the crib and scooped his daughter up into his arms. Check for leakage, the Old Dad instincts told him. Structural integrity may be compromised. All appeared to be well, though Rebecca’s distress level was sharply rising. Lowering his daughter gently onto the changing table in the corner, Sisko unfastened the diaper, tossed it into the recycler, smiled briefly at the tiny, perfect derriere, then gave it and all other visible parts a thorough but gentle wiping. A spray of powder, then a new diaper, and voilà, all was sealed and in place, and the proud papa stopped only long enough to inspect his daughter’s rounded belly. The baby, whose face had been in danger of scrunching up for a howl, suddenly became aware that something significant had changed; she stopped and considered. Ah,the face said. Better. But all is not well.The lips pursed and Baby Rebecca, Princess of All She Surveys, screwed up her face in a yawp of discontent.

“Well,” Sisko said, and carried the unhappy child to her waiting mother. “I can’t help you with that.” Kasidy slid down the corner of her gown, nestled Rebecca next to her breast, and then covered them both again. The mouth searched, Kasidy guided her head, and then there came a coo of satisfaction. Sisko bent down and pressed his face into his wife’s neck, inhaled again: yes, all still there—face cream, milk, powder, love.

Kasidy wriggled away from his rough cheek, smiled, asked sleepily, “What time is it?”

“Early. Go back to sleep.”

“Yougo back to sleep. You were up past two last night talking to Jake and here you are up again with the birds.”

“I’m not tired.”

“You’re never tired.”

Grinning, Sisko stroked his wife’s hair. “The Prophets didn’t believe in getting up early. And they’re very leisurely about how they spend their mornings. Slippers. Sweatshirts. Two cups of coffee before they even think about what’s for breakfast. And then naps all around in the afternoon.”

Kasidy stroked the baby’s fine curls. “Sounds like it would drive you mad, Mr. I Must Be Up and Doing.”

“That’s why I had to come back.”

“Oh, right,” Kasidy said. “That was why.”

Sisko straightened and listened to the morning. The shuff, shuff, shuffof the fan drowned out a lot of noise, but he was fairly certain no one else was stirring around the house. Birds out in the hedgerow were busily tending their own families, adults making sure their almost-grown chicks were ready to fly. “Coffee,” he said aloud, knowing Kasidy didn’t hear him; she was already asleep again, Rebecca snuggled close. The baby had stopped nursing, asleep, but her mouth was still firmly attached to her mother’s nipple, close, close, so close. Closer to Kasidy than any other human being ever would be. Sisko touched the child’s cheek and said, “This is why.”

As Sisko stepped from the bedroom, he slipped his arms into the sleeves of his robe. Summer came on slowly in Kendra, evidenced by the cool air from the northern mountains mingling gently with the breezes blowing off the Yolja River. This morning was warmer than the one before and tomorrow would be even warmer, but for an old New Orleans native like himself, anything below thirty Celsius warranted a wrap. Still, Sisko did not wish away these cool mornings. Each graduated environmental change bespoke time passing and he savored the sense of being reconnected to its flow.

Enjoying the way the flesh of his arms prickled slightly in the cool air, Sisko strode into his kitchen only to be greeted by the whiff of overripe garbage. I thought I’d asked Jake to take that out to the compost pile.Searching his memory, Sisko had to admit that he could only remember thinking about asking Jake. After all, between the two of them, they had drunk two bottles of the good spring wine last night and he, Sisko, had probably downed more than his share. The nursing Kasidy would only wet her lips with it during dinner. And Jake…

Where wasJake? On the floor next to the couch were signs of his nest, a loose roll of blankets and a well-scrunched pillow. The shades that had been drawn over the sliding door to the garden had been pulled aside. Sisko padded softly to the door and looked out.

Shoulders hunched, his son was standing in the garden staring into the south, hands thrust deep into his jacket pockets, shadow long behind him, morning dew soaking into his boots and pant legs. Lost in thought, Jake did not hear his father as he pulled the sliding door open. Glad for the opportunity, Sisko stood and regarded his son as dispassionately as he could. He’s grown up to be a fine-looking young man,the father thought. Or maybe I need to stop saying “young man.” He’s a man now. No “young” about it.Sometime in the past week, Jake had decided to stop shaving, and the unruly stubble of a couple of days past had already become a thick tangle. Everyone had teased Jake about it for a day or two, but Jake had known the change was blessed when his stepmother had run a hand over his chin and commented that all the Sisko men looked better with beards.

But what is he thinking about?Sisko wondered as Jake absentmindedly rubbed his chin. Never an early riser, this one, not unless he has something on his mind.Sisko amended the thought. Or when he’s working on a story, but then it’s not getting up early; he just doesn’t sleep.But Jake had not been working on a story or, near as his father could tell, much of anything since Rebecca was born. Considering it now, he realized that Jake had been looking restless the past couple of days. Thinking about the past, he concluded. And thinking about the future. Thinking about anywhere but here.

“Hey, Jake-o,” Sisko called. “Aren’t your feet going to get soaked?”

When he heard his old nickname, Jake’s shoulders slowly stirred and he shook off his reverie. Turning toward his father, he smiled the familiar old smile, the happy grin of open, unaffected pleasure, though Sisko felt a peculiar nostalgia creep over him seeing the smile through the beard. It was like when Jake was ten and had just discovered stage makeup. Marveling that he had not thought about it in over ten years, Sisko remembered that summer—the pancake makeup, the spirit gum, the hair appliances, Jennifer chasing a half-denuded werewolf out of their bathroom. How many bathroom towels had the boy ruined?

“Hey, Dad,” Jake responded, though not too loud. He looked down at his drenched boots, then lifted each one off the ground in turn. “Too late.”

“Then no reason to hurry in,” Sisko said. “Unless you want to help me make breakfast.”

Jake’s eyebrows lifted. “French toast?”

“Do we have sourdough?”

“I made a loaf yesterday.”

Sisko beamed. “I brought you up right, didn’t I?”

Jake shrugged, and Sisko saw the smile turn down a little at the corners. Then, in a moment, it was gone and Jake replied, “Yep, you did.” Looking again into the south, Jake pointed out across the rolling hills and asked, “Do you know what’s in that direction?”

Sisko considered. He knew the names of all the major land-masses on Bajor—the general composition of each continent and their positions relative to each other and the oceans. He imagined he knew as much as any average high-school student, which was to say a lot about a few places and a very little about many others. He answered, “Valley plains and forest spreading out on either side of the Yolja for hundreds of kilometers, and then the sea.”

“Anything on the coasts?”

“The usual sort of thing: fishing towns, light industry, ocean farming. No big cities due south of here, though. Why?”

“Just wondering,” Jake said as he stared into the rising sun, then added, “Mrs. O’Brien tried to teach us about Bajor’s geography, but I don’t think too much of it stuck.”

“Not everything does, son. It’s not like we lived here.”

Nodding, Jake said, “But we do now. You do now. I guess I just feel like I’m a guest here. It’s not my home. I guess I always thought that we’d end up back on Earth again.”

Smiling, finally understanding, Sisko replied, “Well, that’s up to you, isn’t it?”

“Yeah. Guess it is.”

Sisko felt a chill creep up through his feet. It was too cool to be outside without shoes, and his robe whipped around his knees in the morning breeze. “I’m going to go start breakfast. You want coffee or tea?”

Still staring into the purple and gold sky, Jake said, “I’ll wipe my feet before I come in, Dad.”

Shaking his head, Sisko ducked back inside.

Kasidy

Ten minutes later, just as the coffee was beginning to perk and the tea water was coming to a boil, Kasidy came into the kitchen, face scrubbed, hair held back with a headband, and baby Rebecca over her shoulder. After kissing her husband, she spun around and showed baby to daddy, who stopped sawing at the loaf of sourdough long enough to say, “Hi, sweetie,” and wipe baby’s spit-up-covered chin with the towel he had over his shoulder.

Kasidy lowered the baby into the crook of her left arm, found herself a teabag, and dropped it in the mug Sisko had left on the counter next to the hot water. “Where’s Jake?” Kasidy asked as she poured. He’s not out on the couch.”

“Outside.”

Kasidy pulled aside the curtain over the kitchen window and peered out. “What’s he doing?”

Sisko sawed off another slice of bread. “Trying to figure out how he’s going to tell us he’s leaving.”

“Ben?”

Happily engaged with his egg beating, he didn’t look up. “Hmm?” he asked.

Kasidy said, “I’m going to go talk to him.”

“Then I won’t make your toast yet,” he said. Looking up at Rebecca in her bouncy chair, sucking her fist contentedly, he grinned and said in the high, excited tones the baby responded to, “I’ll talk to Miss Rebecca. Yes, I will. We’re going to have a nice chat.”

Surprised, she asked. “Aren’t you going to tell me to leave him alone? No ‘He’ll come in when he’s ready’?”

Placing the bowl of batter in the refrigerator, Ben shook his head. “Why would I say that? You’re his friend. More, you’re family. If I were him, I’d want you to come out.”

“Oh,” she said, not knowing what else to say.

“Not what you were expecting?” he asked as he stooped to lift Rebecca out of her chair.

“Not exactly. Are you sure the Prophets didn’t do anything to you while you were gone?”

Sisko made a “Why would I tell you the answer to that?” face, then offered a finger to Rebecca that the baby promptly grasped with raptorlike force and pulled toward her mouth.

“She shouldn’t be sucking on your dirty fingers, Ben,” Kasidy said.

“Babies,” said the Old Hand at Parenting, “do whatever they want to do and nobody can tell them they shouldn’t.”

The sun was high enough in the sky that the dew was rapidly drying and the kujaflies were beginning to spiral up in loose clouds from the grass. Another half-hour and it would be unbearably warm out in the sun. Jake had his head tilted back, eyes shaded, intent on something high up. Stepping out from under the arbor, Kasidy saw what he was looking at: a black shape drifting in slow, lazy circles. Kasidy’s pilot instincts kicked in and she judged that the shape might be as high up as a thousand meters and must have a huge wingspan—at least four meters and maybe as much as six.

“Wow” was all she could think of to say.

“Yep,” Jake answered.

“Glider?” she asked.

“Nope,” Jake said. “It was a lot lower a few minutes ago and I saw its wings pump. Whatever it is, it’s alive.”

“I repeat,” Kasidy said. “Wow. I’ve never seen anything like that around here. Do you have any idea what it is?”

“None,” Jake said. Then he added a bit testily, “I’m not the one who lives here, though.”

“Less than a year,” she said, trying not to sound too defensive. “And I’ve been too busy to do much bird watching.”

Jake looked down at her, hand still shading his eyes, and said, “Sorry, Kas. I didn’t mean it that way.”

“ ’Sokay, Jake.” She took a half-step closer to him, then took his arm loosely in her hands to steady herself.

“They used to have avians like that in South America,” Jake said. “On Earth.”

“I know where South America is.”

“Right.” Again, he sounded apologetic, but only barely. “Anyway, one was called Ornithochirus.Huge wingspan. It lived most of its life in the air because it could barely move on land. It had to live near cliffs because the only way it could get off the ground was by jumping off something high.”

“A pterosaur?”

“Yeah.” He looked down at her. “How do you know about them?”

“I had a dinosaur phase when I was a kid.”

“Really? Me, too. How old were you?”

Kasidy thought back. “Five. Maybe six. I liked reading about them.”

“I memorized all the names,” Jake said.

Shaking her head, Kasidy said, “Didn’t do that, but I liked looking at holos of them.”

“Did they have dinosaurs on Cestus III? Something like them?”

They had talked about Kasidy’s homeworld on several occasions, but always in the context of her growing up there and leaving it. “There were prehistoric creatures, sure, but nothing really big before humans starting settling there.”

Jake lowered his gaze and stared out again toward the horizon. “How about here on Bajor? Did they have anything like dinosaurs?”

Kasidy had to admit she had no idea. “We should check. I imagine that’s exactly the kind of thing Rebecca is going to be asking me in a few years. Or, more likely, telling me about.” The idea made her smile. “I guess she’ll be just like me—reading about Earth and learning about dinosaurs and wondering what it would be like to find some kind of gigantic bone buried in the sand.”

Jake didn’t reply for several seconds, and then he said simply, “I feel like I don’t know anything about anything.”

Ah,Kasidy thought. Here we are then.Aloud, she said, “What do you mean? It’s always seemed to me that you know a lot of things. A lot more than I did at your age.”

Scowling, Jake said, “I know a lot of facts. Sometimes it feels like I don’t even know many of those.” Pointing out to the south, he asked, “Do you know what’s out there in that direction?”

Again Kasidy admitted that she did not. Geography had never been her strong suit, and these days she was not very concerned about anything farther away than the horizon.

“Neither do I,” Jake said, the self-disgust making his voice tight. “I have no idea what’s out there.” He tapped the side of his head and added, “And no idea what’s in here, either.”

Kasidy sensed how delicate the situation was and did not know whether she should err on the side of sympathy or truth. “You’ll figure it out,” she said trying to find a compromise. “You’re a writer. That’s your job.”

“Is it?” Jake asked. “And am I? I’m not too sure.”

This is worse than I thought.Kasidy decided that sympathy was no longer useful. “Stop it, Jacob Sisko,” she said sharply. “I’m not going to listen to you indulge in self-pity. You know you’re a writer. If you’re having trouble with something right now…”

“But that’s just it!” he exclaimed. “I’m not doing anything right now!” Looking down at her, eyes wide, he said, “I can’t seem to think of anything I want to say right now. Everything seems either too big or too trivial. I can’t make sense of it, can’t get any perspective!”

“Oh, sweetheart,” Kasidy said, trying to soothe her friend, “that will come. A lot has been happening the past year: The end of the war, your father disappearing, your adventures in the Gamma Quadrant, finding Opaka and the Eav-oq, your father coming home, Rebecca being born. That’s a lot for anyone, let alone for someone…” She bit her tongue, hoping he would let the sentence pass.

He didn’t. “Someone?” he asked. “Someone what? Someone who?”

She gritted her teeth. There was no escaping it now. “I was going to say, ‘Someone so young.’ But that’s not what I meant. I just meant…you’ve had an extraordinary life, Jake. All kinds of things have happened to the people around you….” Wincing, she realized her mistake too late.

“Exactly!” He shouted, arms flung wide. “To people around me! But never to me!”

“Now, don’t do that, Jake,” Kasidy protested. “You had your adventures on the Even Odds.Don’t make it sound like you’re nothing but a bystander. You’ve seen more in your short span of years than most people see in a lifetime.”

“Then why can’t I write about any of it?!”

Frustrated, Kasidy decided it was time for direct action. Balling up her fist, she punched Jake in the arm as hard as she could.

“Ow!” he shouted. “What was that for?”

“Did it hurt?”

“Of course it hurt,” Jake said, rubbing his shoulder. “You’ve got bony knuckles. That’s going to leave a mark.”

“And you know why it hurt?” Kasidy asked, but didn’t wait for an answer. She was angry. These Sisko men,she thought. So brilliant and so dense.“I’ll tell you why: Direct stimulus. You get a shot in the arm and you feel it right away. One shot and you feel it very cleanly and clearly. Now, let’s talk about everything that’s been happening to you lately. Let’s say that they’re the same as getting one shot after another after another. Understand?”

Jake took a half-step away. “Maybe. You’re not going to hit me again, are you?”

“No,” Kasidy said, her tone softening. “But if I did, what would that be like? Would you necessarily feel each punch if I got you three or four more times?” She held up her clenched fist. “With my bony knuckles.”

Wincing, Jake admitted, “Probably not. My arm would go numb pretty fast.”

“You see my point now, don’t you?”

Jake continued to rub his arm, but his gaze had drifted off to the horizon again. “I think so,” he said. Then, with more conviction, “Yeah, I think I do.”

He keeps looking out at the horizon.Grabbing his arm and gently rubbing it, she remarked, “Your father said you were thinking of heading out.”

Annoyance flickered across Jake’s face. “Did he?” he asked. “I didn’t say anything to him. Well, what if I did? Where would I go? Back to Earth to see Grandpa? He was just here and, frankly, I don’t feel like cleaning oysters. Back to the station? I’m not sure I have a life there, either.”

“No, silly,” Kasidy said cajolingly. “Not anywhere out there. Not on a ship or using the transporter. Use your feet. Pick a direction and start walking.” She felt him stand a little taller, as if he would be able to bring the horizon closer. Kasidy felt something in his shoulders relax.

“The house feels too small for all of us,” Jake said, his voice cracking a little.

Whatever it was that was coming up out of him was costing him. Good,Kasidy thought. It should.“You understand,” she said aloud, “that it doesn’t feel that way to us. Only to you. And it should, too. Young men aren’t supposed to like living with their parents.”

Jake tore his eyes away from the horizon and looked down at her. The tightness around his mouth disappeared and was replaced by a slow smile. There it is. The smile. The old Jake.“How did you ever get to be so smart?” he asked.

Kasidy rolled her eyes and grinned. “ ‘Always hang around people smarter than you are and you’re bound to learn things.’ One of the few pieces of good advice my father ever gave me.”

He opened his mouth to reply, but before he could say a word, Kasidy saw Jake flinch and hunch his shoulders. Ducking his head, he lifted his arm protectively, as if shielding her from a blow. Looking up and around his arm, she realized that they had both forgotten about the hovering black shape. Somehow, instinctively, Jake had sensed a change in its disposition. The creature, whatever it was, had tipped its wings back along the sides of its body and was now streaking toward them, growing larger by the second. A tiny ground-living mammalian voice from the back of her mind chittered, Crouch down low and hope it doesn’t see you!,but Kasidy tried to ignore it. The sane, sensible part of her, the part that had accepted the fact that she was married (for better or worse) to the Emissary, was sighing, Okay, now what?Abruptly, the creature changed trajectory and winged away from them, slowly losing shape and form until it became a dark blot against the brilliant morning blue, then vanished from sight.