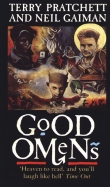

Текст книги "Hero"

Автор книги: Alethea Kontis

Соавторы: Alethea Kontis

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

8

Epiphany

“BETWIXT! PRAISE the gods. I had quite despaired.”

Peregrine halted his as-yet-infernal lute playing to greet the chimera slinking into the cave with quiet grace. It had been a good long while since Peregrine had last laid eyes on his friend. The chicken-footed scorpion body had morphed into a sleek black gryphon of the smallish variety, much like a young panther with charcoal-gray wings.

“If you despaired, it’s only because you tired of your own one-sided prattle.” The chimera’s head was thankfully more leonine than bird, leaving his mostly mammalian mouth free to converse, though the words that came out were a bit high– pitched and nasal.

“You know me so well. Shall I play you a tune to celebrate your triumphant return?”

“Have you learned to play anything even closely resembling a song on that?”

Peregrine gave his companion a wide and silly grin and curled his toes against the pillar on which he perched. “Not at all. But I could get the flute . . .”

“Don’t trouble yourself.” Betwixt wandered around the room a bit before circling and settling himself in a cold spot away from the lantern. The chimera craved warmth when he was in a solid state. Right before a change, or right after, he craved the cold. His wings folded neatly over his haunches and his tail waved back and forth lazily. “So, how goes it with our young prodigy?”

Peregrine resisted snapping a lute string, as he wasn’t likely to find a ready replacement. One learned to take good care of one’s belongings when there was a limited supply. “She’s still digging herself deeper into that bird’s nest. I don’t think she’s ever going to ask me for help. Jack Woodcutter neglected to mention that his sisters were stubborn brats.”

Betwixt scratched his jaw with a hind leg. “There are six other days of the Woodcutter week. They can’t all be so badly– tempered.”

“I pray not, for Jack’s sake.” Peregrine’s hopes for conversation and companionship had so far been dashed by this girl. She worked harder than her brother ever had, and tirelessly. Peregrine had woken and slept three times since the witch had set her to her task. He’d checked in on her, but she hadn’t spotted him, so he didn’t interrupt. Deeper and deeper she buried herself in the filth of the witch’s familiar. She had yet to figure out the trick to the enchanted rake, and Peregrine refused to involve himself where he was not wanted. He had eventually tired of waiting for her to ask for help and had gone about his daily business as usual.

Only, there was nothing usual about his daily business anymore. He’d been lonely as a child with an ill father, but that loneliness had been eclipsed by his years of solitude at the Top of the World. And yet, having someone else close at hand who pointedly ignored him made him feel worse than he ever had before.

This hadn’t been the case when Jack had scaled the mountain. There had been the swapping of laughter and stories. When Jack had asked Peregrine to escape with him, Peregrine felt comfortable enough beneath Leila’s disguise—especially now that the witch had been blinded—to be secure in his decision to stay and sabotage the witch’s experiments. The world would go on as it should, none the wiser, for as long as he could manage it. “When Jack was here, he spoke of his family as if he’d only just left them.”

“Did he? It was so long ago, I barely remember.”

“It wasn’t that long ago.” Betwixt did tend toward hyperbole. “But the day Saturday arrived—”

“That day I remember.”

“Saturday mentioned not having seen Jack since his voyage to the White Mountains. Do you think something’s happened to him?”

“Oh dear. I hope not.”

“As do I,” said Peregrine. “The Goddess of Luck seemed to be ever at his side; I only pray she still is.”

“Luck can be bad as well as good,” Betwixt pointed out.

“I wish I had better luck with Saturday,” said Peregrine. “I want to help her. What’s so terrible about that?”

“You’re just bothered that she doesn’t give two figs for you,” said Betwixt.

“Of course I am. Do you think the skirt is putting her off? I fear it makes her see me as weak.”

“I think the witch has put her off more than you or me,” Betwixt suggested. “To be honest, I don’t believe she’s seen you at all, weak or not, since she’s been here.”

The idea took away some of Peregrine’s bluster. He didn’t want to think of what would happen when “Jack Woodcutter” finished all the witch’s tasks and still couldn’t find the eyes. “She’s obsessed with that room. She’ll work herself into the arms of Lord Death at this rate. What kind of person burdens herself so much when help would be given freely and willingly?”

“A very strong person. And a very stupid one.”

Peregrine laughed. “Spoken like a true cat.”

“Why don’t you just ask Saturday herself about her intentions?”

“She’d have to stop burying herself in bird dung long enough to talk,” he said.

“Then the Goddess of Luck is with you this day.” Betwixt tilted his head to the sloping archway through which Saturday was determinedly making her way to them. There was a rake in her hands and fire in her eyes.

Everything about her was so familiar to him, as if he’d known her for a lifetime. Pity she didn’t feel the same. They could have been such good friends.

“Hmm.” Peregrine leaned back and casually picked up the lute again. He wanted his image of lassitude to irk her. He should have been ashamed at this pointless goading. He wasn’t.

“Jack Woodcutter! As I live and breathe.” He yawned, and then instantly regretted it: Saturday reeked like a sewer. “Just between us girls,” Peregrine whispered, “that cologne doesn’t suit you.”

“Good morning, Lie-la.” Saturday purposefully mispronounced the name. Oh, he did like her gumption. Shame about the brattitude. “Or day, or afternoon, or evening, not that anyone can tell.”

“Every greeting is welcome in a land beyond time,” Peregrine said poetically, plucking idly on the lute as if he might compose a song with the words.

“Then I should have hugged you and mugged you with slime,” Saturday rhymed glibly.

Peregrine was surprised at her show of cleverness and continued the verse. “Look at Woodcutter! Not bad with a rhyme.”

Instead of answering in kind Saturday turned her face to the floor, as if someone had just scolded her for having fun. “It was a game I played with my brother. Peter, not the one you know.”

Not the one he knew, and not the one she sought. So many siblings! Peregrine could hardly imagine a family so large. “My compliment still stands. If I had your gift, I would write a hundred songs to your malodorous beauty.”

“First, you’d have to learn how to play,” she said. At the snuffled sound of cat laughter, Saturday raised her lantern and spotted the gryphon. “Hello there.”

“Well met, Miss Woodcutter.”

While she had her lantern held high, Saturday turned slowly and examined the sparkling pillars in this cave, like castle turrets made of fairydust. The fingerstones here looked like tall, dripping candles waiting to be lit. It was one of Peregrine’s favorite spots.

“All these caves look mean,” said Saturday. “Full of teeth, like they intend to eat me alive.”

Peregrine blinked at the scene, trying to see it with new eyes. He’d felt the same way when he’d arrived, but in the period that followed the caves had changed. Mellowed. As he had. “The longer you stay, the kinder they appear.”

“Is it true that time doesn’t properly pass in this place?”

“Oh yes,” answered Peregrine. “There is no day or night here, only sleeping and waking. The sun and moon pass overhead, but Lord Time and his brothers have no hold on this mountain. We could live up here a thousand years and never age or die.”

“How do you know?”

Peregrine shrugged. “I’m not dead yet.”

He dodged the swat she intended for him. “You try my patience.”

“Take care with that. If he decides he likes your patience, he’ll take all of it,” Betwixt chimed in.

Saturday pointed at the gryphon with the rake. “Did you used to be the beetle-thing?” Peregrine had to give her credit; he hadn’t caught on to Betwixt’s nature so quickly. Her cleverness aggravated him, but he quashed the feeling. Now that she’d finally come to him, he did not want to ruin it.

“I was. Forgive me for not introducing myself earlier. My name is Betwixt.” The gryphon bowed his head.

“Is that really your name? Or is ‘Betwixt’ a part you’re playing as well?” She looked askance at Peregrine. He simply shrugged his shoulders helplessly.

“It might have been something else so long ago, I’ve forgotten it. Betwixt is the only name I have to give you.”

“I’m sorry,” said Saturday.

“It’s not that bad a name,” said the gryphon.

“I mean that you’ve forgotten your old name,” she corrected. “That happened to a brother-in-law of mine when he was enchanted. Are you enchanted? Is there anything I can do to help? I’m a maiden,” she said bluntly.

“So am I!” said Peregrine.

“You are an im—” Saturday stopped before she finished the insult. Her restraint surprised him. He really wished she’d stop impressing him. It made her lack of interest that much harder to bear.

“Cat got your tongue?” Peregrine asked her.

Betwixt yowled in nasally feline laughter.

Saturday stuck out said tongue to prove that she was still in full possession of it. “I need help,” she said.

Finally! Peregrine resisted the urge to hug the lute giddily. “You need a bath” was all he said in reply.

“Are you going to help me or not?” said Saturday. Her knuckles around the rake handle were white.

“Are you asking or not?”

Saturday put her head down, sighed, and started again. “The witch gave me this”—she thrust the disgusting rake in Peregrine’s direction—“and told me to clean her wretched bird’s nest.”

Peregrine backed away from the rake. He didn’t want it to accidentally touch him. “And . . . ?” he prompted.

“The cursed thing doesn’t work! The more soiled peat I rake, the more there is, multiplying instead of diminishing. It’s some sort of foul magic.”

Peregrine wrinkled his nose. “Something in this cave is certainly foul.”

“I gave up on the rake and tried shoving out the moss with my bare hands for a while.”

“Oh no,” said Betwixt.

“Oh my,” said Peregrine. He wasn’t sure even he had the stomach—or the nose—for that level of degradation.

“But nothing happened! I worked from the time I woke until the time I fell asleep and the room looked the same as it had when I started.”

“So you tried the rake again,” said Peregrine.

“Yes,” said Saturday. “Disaster. Can you help me?”

Peregrine sat and stared at the girl for a while, letting her stew. He suspected she knew what he was doing, but she remained quiet. “Yes, I can help you,” he said finally.

“Name your price,” said Saturday.

“I didn’t say there was one yet.”

“I have siblings,” said Saturday. “I know how this works. Go on, state your conditions.”

Peregrine was torn between the desire to kiss Saturday and the desire to strangle her. It was an intoxicating feeling that amused him no end, but her stench made the decision for him.

“I will you give you a number of sacks,” said Peregrine. “When you clean the bird’s nest, collect the soiled moss in these sacks.”

“Done,” said Saturday. “Is there a supply of clean moss to replace the old?”

“I’ll make sure you have it,” said Peregrine.

Saturday nodded, but she did not thank him. And because she did not thank him, Peregrine continued his list of demands. “I will also have a bath ready for you. When you are done cleaning the nest, you will take it.”

“All right,” she said easily, for this was more of a benefit than a hardship. He’d hoped she’d take it as such. But she still conveyed no expression of gratitude.

“You will come with me wherever I decide to take you, and you will keep a civil tongue in your head.”

“Fine,” spat Saturday. “Is that all?”

“One last thing,” said Peregrine. “You have to fight me for it.”

“For what?”

“For all of it: the sacks, the bath, and the answer to your enigma.”

The smile she gave him was wicked and wonderful. “My pleasure.”

He might have returned the lute first and taken a longer, more circuitous route to the armory, but the girl’s smell was more than he could bear. Betwixt led the way, half slinking and half flying, ever keeping upwind. When Peregrine passed through the archway to their destination he lifted his lantern and turned to see her expression, hoping that he might catch a glimpse of happiness, however small.

He was not disappointed.

Peregrine saw a moment of unabashed joy on Saturday’s face before she noticed him watching and stifled it. “Where did all this come from?” She set down the rake and brought her own lantern in for a closer look.

“If there is one thing a dragon’s lair does not lack, it is the weapons of defeated foes.” One by one, Peregrine lit the torches around the room. He had chosen this section of the caves for its natural shelves, on which he’d separated the weapons into categories. “Axes, maces, lances, bows, arrows. The swords are in a pile over there. There are so many, I’m never quite sure how to sort them.”

“And clean, polish, and sharpen them?” Peregrine nodded in answer to her question. “This must have taken ages.”

“It’s an ongoing project. I enjoy a hard day’s work.”

“Me too,” she said. Peregrine heroically refrained from comparing his “hard days” with her exhausting path of never-ending masochism.

“The results of my work on the weapons are easier to see. Armor is less salvageable as a whole, but there’s still plenty to be had, and it’s excessively useful. Even a dented helmet makes a passable mixing bowl.”

“A mixing bowl.” Saturday seemed to find the notion blasphemous. She let her hand hover over a shelf of oddities, but did not touch them. “I don’t even know what some of these things are.”

“Nor do I,” Peregrine admitted. He picked up one item that had very long spikes connected by a chain. “This one could be a very dangerous whip.”

“Or a collar,” Saturday suggested. “Maybe something attached to a helmet?”

“More likely. Though the skeleton I took it from had it like this.” Peregrine wrapped the chain around his fist, so that the spikes pointed out from his knuckles.

“Wicked,” said Saturday cheerfully.

Peregrine tossed the chain back onto the shelf. “And completely pointless when fighting a dragon. If you’re close enough to punch it, it’s close enough to roast you and eat you.”

Saturday walked to the next shelf, which was full of daggers and sharp throwing implements. “May I?”

“Of course. They come in handy when one needs to chop ice from the walls.” Peregrine had replaced his own broken dagger earlier.

He’d destroyed many a dagger while hacking at the walls of his prison, but there was still a plethora to choose from. Silver, iron, bent, curved, and serrated, they stretched out before Saturday like a smorgasbord of pain. After lifting and balancing a few of the knives, Saturday added only one more to her swordbelt with its empty scabbard.

“Did you bury the skeletons?”

“Of course! Thankfully one of the knights who died here brought a magic shovel that could cut through icerock like freshly churned butter.”

Saturday rolled her eyes at him but did not stomp away. Perhaps there was hope for a friendship between them yet. “Bones have useful properties,” he said seriously. “The warriors here are long dead, as are the ones who mourned them. The only living being to come up this far in recent years was Jack.”

“Right,” said Saturday. “You mentioned that.”

Peregrine took her hand. “You really haven’t seen your brother, have you?”

Saturday pulled her hand away, scalding him again with those eyes of fire. The feeling that he’d known her forever struck him again.

Peregrine wondered why he kept trying to please her and realized it was because of Jack, but Jack had enjoyed himself during his stay. Peregrine couldn’t stop from asking, “Do you enjoy anything?”

Saturday exhaled. “Can I just fight you now? Please? I’d rather die than continue this conversation.”

“Oh, this is going to be fun.” Betwixt leapt to a shelf beyond sword’s reach and settled himself comfortably.

Peregrine curtseyed. “As milady wishes. But you can’t have so little faith in your abilities. I’m sure you’ve had teachers more recently than I.”

“My sword was my nameday gift. As you know, it’s enchanted. I’m not so good without it, despite my teachers’ attempts.”

Peregrine indicated the pile of swords. “So choose another one.”

Saturday put her hands on her hips. “None of them is my sword.”

“But many of them are enchanted,” said Peregrine. “Most of them, I’ll wager. One doesn’t hear many tales of men going up against beasts like our dragon with only their wits and cold steel.”

“Unless those tales are about Jack Woodcutter,” she said under her breath.

Peregrine had heard few tales of such men as a boy in Starburn; bedtime stories in the north typically ventured into the realms of gods and monsters. But having met Jack, he could imagine the kinds of stories that confident swagger left in its wake. As many hearts broken as curses, he’d wager.

“Well, then, let’s see if you live up to your reputation, Mister Woodcutter.” Peregrine pulled a sword from the pile at random and unsheathed it. The hilt’s basket was ornate and set with dull jewel chips. The blade was thin and glowed a red that tinted the crystal walls around them a sinister pink.

“What does that sword do?” asked Saturday.

“No idea,” said Peregrine. “Hurry up and pick one so we can find out. Who knows? You might decide you like something here better than the one you had.”

“Doubtful.” Saturday took a little longer over her selection. The sword she chose was far less decorative, with only crude runes etched haphazardly into its pommel, grip, and cross guard. It looked ancient, and heavy, and didn’t have much of an edge. She’d have more luck using it as a club. Perhaps that was her plan.

Peregrine took up the stance his father and swordsmaster had taught him: arm held up and blade pointed down. Conversely, Saturday held the hilt at her center of mass with blade pointed skyward. He tried to remember which of the regions of Arilland Jack had said her family was from. “En garde.” He hoped she knew what he meant.

He did not expect her to say, “This grip is warm.”

“You’re welcome to choose another sword,” he offered. “We have all day, night, afternoon, and evening, or until the witch finds us.”

“No, this sword is fine. It’s just . . .” As she spoke, the sparkling runes from the hilt duplicated themselves on the skin of her hands, her wrists, and then her arms. She drew in a sharp breath, but she did not let go of the blade.

Peregrine worried for her safety. “What’s happening? Saturday, talk to me. Are you all right?”

She looked up from her silver rune-covered arms and her bright eyes flashed above that impish smile. The dirty locks of her hair framed her face. “I’m perfect,” she said, and struck out at the red blade.

Peregrine dropped his sword.

He did not drop it on purpose; he’d fully intended for the two of them to fight evenly and fairly. But what Peregrine had just seen beyond that ancient blade, atop smelly limbs and a neck now covered with glowing runes, was neither the face of Jack Woodcutter nor that of his far less likeable sister.

The face that had grinned at him with those bright eyes was the face of the woman from his visions.

Betwixt had been right: Elodie of Cassot was not the woman of his dreams after all. The image he’d been seeing for most of his life had been that of Saturday Woodcutter.

The familiarity he’d been sensing crashed like a wave in his heart. No words sprang to mind to describe the feelings this epiphany swept through him, but the ones that came closest were not meant for mixed company.

“Peregrine?”

Peregrine snapped out of his trance. “I’m sorry,” he said to the chimera, and he picked up the sword again. “You’re completely covered in those runes now,” he said to Saturday. “Are you sure you’re all right?” He was amazed he was all right enough to string coherent sentences together.

“Perfectly lovely,” Saturday said pettily. “Are we doing this or not?”

He wanted to stop the argument, sit her down, and ask her a barrage of questions. But more, he wanted to watch her, to see the face burned on his soul bearing down on him in real life. Peregrine resumed attack position. “Best two out of three?” he asked cheerfully.

“Prepare to die,” said Saturday.