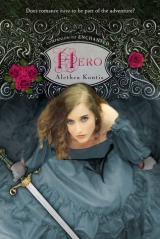

Текст книги "Hero"

Автор книги: Alethea Kontis

Соавторы: Alethea Kontis

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

3

Godstuff

“WHOA!”

Wind whipped. Horses whinnied.

The clattering of carriage wheels. A door opening and slamming.

“Mama?! Papa?!” A woman’s voice like an angel. Frightened.

Monday.

“Here. In the kitchen.” A deep voice with a common accent, trying to stay calm.

Erik.

“Are they . . . ?” asked the angel.

The rumbling answer was too low to be understood.

Saturday tried to open her eyes. The light that slipped between her heavy lids stabbed mercilessly at her brain.

Painpainpain.

She closed her eyes and concentrated instead on sounds. The two voices swam in and out of clarity, both strange and familiar. She tried to make sense of them through the pounding of a heartbeat that crashed like waves in her ears. The squealing birds outside the window made a horrible high-pitched racket.

Erik and Monday would be looking for her. Saturday had no strength to cry out. She slid a tongue between dry lips and tasted salt there. Was she bleeding? Had she hit the stones when she fell? She opened her mouth to scream, but all she managed was a wheezy moan. Try harder. She must tell them what had happened, tell them about Trix. She had to make sure Papa and Mama and Peter were all right.

First, she needed to figure out a way to get down all those stairs. The thought alone exhausted her, but concern for her family urged her onward. She leaned against the sheathed sword at her belt and used it to stand, but it tangled in her legs as she tried to walk. After stumbling twice, Saturday unfastened the swordbelt and removed it.

The moment her body stopped making contact with the sword, she felt a thousand times worse. Her stomach clenched, spasmed, and threatened to rebel. Daylight blinded her as it bounced off the cloud cover framed by the casement. One by one, her disobeying limbs began to shut down. Before she completely passed out again, she forced a hand out and grasped the hilt. Energy and relief flooded through her. Trix was right: the sword’s magic actively fought off the sleeping spell.

“Aren’t you handy,” she muttered. With the sword no longer attached to her person but still sheathed, Saturday used it to stumble and crawl down the many steps from the aerie. Oh, if Velius could see her now, forced to use her gift as a literal crutch. He would laugh himself silly.

Erik must have heard her less-than-graceful descent, and met her on the last flight of stairs. Careful not to knock the sword away, he slipped an arm beneath her shoulder and encouraged her to lean her weight on him. She reluctantly obliged.

“Not going to carry me to safety, Hero?” Saturday teased him, but her words slurred together as if she’d been swilling Grinny Tram’s honey mead. The lack of control frustrated her.

Still, Erik seemed to understand her. He’d no doubt helped more than one mumbledy-mouthed guard back from a tavern in a similar fashion. “And throw my fine back out, Giantess? You must be joking.” But his arm did tighten around her waist, and she felt a few pounds lighter as they crossed the living area. When they reached the kitchen, he announced, “I found her,” and lowered her into Papa’s chair by the fire.

Saturday’s face was immediately filled with Monday’s hair as her eldest sister embraced her. Saturday would have reciprocated, had her limbs not been still full of rocks. But her strength was slowly returning. She patted Monday’s voluminous skirts and repeated, “Really, I’m all right,” in response to her sister’s cooing. Over her sister’s shoulder, Saturday could see Mama, Papa, and Peter, heads down on the dinner table, as she’d left them the night before.

The night before. It was daytime now. She’d slept the whole night through. Trix was half a day ahead of them now, assuming he hadn’t stopped to rest. But he probably had stopped to rest, so he couldn’t have gone that far. If Monday and Erik let her have one of those horses she’d heard, she’d be able to cross the meadow and catch up with—

Saturday’s gasp died as she choked on Monday’s mass of golden curls. Monday backed up to let her sister breathe, allowing Saturday to see Erik standing at the open back door. Wild gusts of wind whipped at his hair and sleeves; the fabric danced like the exiting storm clouds and the waves crashing on the impossible ocean beyond him.

Saturday slowly raised a hand to her mouth. The salt on her lips hadn’t been blood. That hadn’t been her heartbeat pulsating in her ears upon waking like waves on the ocean—it had actually been waves on the ocean. Above those waves cried a cacophony of gulls and shorebirds, fishing and flirting with some very confused cousins from the Wood. The Woodcutters’ little towerhouse was leagues from the nearest shoreline. Or at least it had been.

“I’m dreaming,” whispered Saturday, for that was the only sound explanation. The cries of the gulls mixed with the cries in her mind of the drowning people she’d seen in Monday’s mirror. Now she knew how Thursday felt when she saw the future. Her stomach rebelled again, but not from spelled stew.

“It is no dream,” said Erik.

“What happened?” asked Saturday.

“There was a wicked storm, the air rumbled, and the earth broke,” said Erik. “It was like nothing I’d ever seen before. It still isn’t.”

“Rumbold and Sunday are trying to assess the damage and keep everyone calm,” Monday explained. “The palace is in chaos. They could not get away, but we came as soon as we could.”

“I felt the rumbling,” Saturday said. “Right before I fell . . . asleep.” She wasn’t sure what else to call it. Trix had poisoned them all and run away. Had he done this, too, so they couldn’t follow him? Was this some sort of wild animal magic?

“Perhaps you should tell us what happened here first,” said Monday.

Saturday was starting her story in the wrong place again. She persuaded her fuzzy brain to remember. “A messenger came.”

“Conrad,” said Erik. “Yes, he brought us the same message.” Monday tried to interject something, but Erik stopped her, urging Saturday to continue.

“Mama was upset.” It took Saturday an incredible amount of energy to open her mouth wide, work her tongue properly, and make her words understood, but she managed it slowly and surely. “Trix got quiet. Papa sent the messenger to the palace. Mama went to pack. Trix said he didn’t want to go with her. Peter and I set the table.”

“Trix said he didn’t want to go?” asked Monday.

“If he’d stated his intentions, Mama would have forbidden him, and then he would have been compelled to stay. He planned it that way. He told me so as I was falling asleep. Right before he ran off.”

Erik chuckled. “Clever little bugger.”

The anxiety that came with retelling the tale woke Saturday up even more. “He stirred the pot, Monday. He took over stirring the pot when Mama got the message, and we were all so tied in knots over the news that no one bothered to tell him to stop. And when the stew tasted so good”—she could still smell the cold leavings in the bowls on the table and the burned remnants in the stewpot long boiled dry—“Mama didn’t even scold him. But she made me eat, even though the sword didn’t want me to, because she can’t ever keep her mouth shut.”

It wasn’t fair of her to say that about Mama, but Saturday got swept up in the telling and she wanted to get it all out of her. Besides, Mama was still snoring softly on the table. “Trix poisoned us. He poisoned us, and he didn’t care, not one bit. Did he make the ocean too?”

“This is no fey magic, wild or otherwise,” said Erik, nodding to the view outside the door. “This is godstuff.”

“Why would the gods make an ocean?” Saturday asked.

Monday turned her gaze from the watery horizon and shrugged. “Why not? The gods are responsible for miracles and misery alike.”

Erik and Monday shared a look across the room that spoke volumes, much like Saturday and Peter did, only Saturday didn’t understand this secret language. Erik bowed his head and resumed his interrogation. “Did Trix take something from the library? Is that why you were up in the tower?”

Saturday shook a head that felt considerably lighter. “I wanted to see which way he ran,” she said. “I thought I could call him back. But he was already too far, and the sleep was taking over my body. I was so angry! I screamed at him and I—” The room lost focus as Saturday recalled what she had thrown from the window of the aerie, and the tremors she had felt right before she’d surrendered to the fairy-poisoned stew.

She’d killed him. In a fit of rage, Saturday had killed her little brother.

Peter stirred at the table. Mama and Papa had stopped snoring. Saturday white-knuckled the sword’s pommel to give her strength, physically and mentally. She sat up in the chair, ramrod-straight. “It was me,” she confessed to the kitchen. “I called the ocean.”

This was what Monday’s looking glass had shown them: the flooding, the terror, the storm. Wind and rain and death. Monday had asked Saturday who she was, and only then had the mirror sprung to life. Perhaps it didn’t know what Saturday was, but it knew who she would be: a chaos dealer. A murderer.

Why hadn’t she paid more attention? Why hadn’t Monday said anything? But Saturday didn’t bother chasing after futile answers. Peter had told her often enough that she was as unstoppable as a runaway horse. The visions in the looking glass had been as inevitable as day after the dawn.

Even the sword couldn’t lend her enough courage to voice the rest of her crime. Silence was the only immediate comment, and that was lost to the task of tending to Peter and Papa and Mama’s waking. One by one, Monday and Erik checked to make sure they were each all right, ignoring specific questions until Mama said, “Someone had better explain what is going on, right now!” So Saturday’s tale waited that much longer for the telling.

“Slowly,” Erik advised Mama, who, wincing, put her hand to her head. “One step at a time,” he said softly.

“Trix,” said Papa. “Gods bless that boy.”

“He magicked the stew,” Peter deduced, wincing like Mama had at the sound of his own voice.

“Yes,” said Erik. “And he ran . . .” He looked to Saturday for help.

“North,” said Saturday. “Across the meadow, alongside and away from the Wood.”

“Fool child,” said Mama, but with care instead of anger. “He’s gone to the abbey by himself.”

“I agree with you,” said Erik. Saturday stopped herself from chuckling—the soldier was a quick study. A good way to keep Mama happy was to constantly remind her how right she was. “Do you have any idea why he would have gone to such lengths to travel alone?”

“No.”

Erik tried to be reassuring. “He can’t have gone far on foot.”

“He won’t need to,” said Peter. “The animals will help him.”

Guilt burst from Saturday’s lips. “But the ocean! I’ve killed him!”

Any other sister might have warranted hugs and petting. For Saturday, Peter harrumphed and put a hand on her shoulder. “Trix is fine. He can travel three times as fast as any of us. He just asks the animals.”

“But you don’t know for sure,” said Saturday.

“Yes, we do,” said Monday. “The animals aid him whenever they can.” She rubbed her arms briskly against the cold bite of the breeze in the warm, salt-aired kitchen. “They will also protect him. Wherever he is, he’ll be fine.”

Saturday felt sick in her bones. Her siblings’ reassuring words bounced off her thick skin. There was a dread in the pit of her stomach she could not ignore, and it nagged at her. The only way to know for sure that she hadn’t killed her brother was to see for herself.

Mama wisely said nothing and simply nodded. She knew too well what it was like to doom one of her children to death.

“He’ll be fine until I get my hands on him,” Peter growled. He met Saturday’s eyes and they both smiled. Peter’s bark was far worse than his bite. She’d been on the receiving end of that bark often enough to know. But then Peter’s smile fell. His brow furrowed, and he cocked his head at her. She answered the question he didn’t ask.

“I was the last to fall asleep,” she said. “Trix bade me farewell, after he poisoned us all.” So maybe it was fairy magic instead of poison, who cared. It worked the same way. “I tried to talk some sense into him, but he’d made up his mind. I offered to go with him, but he refused my help. He left. I got mad. And then I broke the world.” She pointed at the wide-open door leading to a wider-open landscape.

Slowly, Peter, Mama, and Papa stood and followed Monday into what was left of the backyard before it fell away into endless waters. The sun burst through cracks in the clouds now, and the sea was calmer. But it was still the sea.

Saturday stood with them, her strength fully returned, and breathed in a deep lungful of salt air. She’d sat beside lakes and creeks and rivers, but this water was alive, mesmerizing and chaotic, gorgeous and unforgiving. It scared her. Who knew how many innocent lives she had taken in her heedlessness? She had no business making such a thing happen, and yet here it was. Papa put his arm around her.

“Nothing small for you, eh, m’girl?”

“No, sir,” said Saturday. She prayed that the gods had spared as many lives as they could. Miracles, like Monday had said. Hundreds and hundreds of miracles.

“What’s happened to the barn?” cried Mama. “All that lovely dry hay wasted! And no place left for the chickens to run, and nowhere to hang the laundry. Good thing I kept the goose in the pantry, despite everyone’s grumbling. There will be no pies this winter if the apples are gone too.”

Chickens? Pies? Saturday had possibly just murdered hundreds of people. There were waves lapping upon their back doorstep, and all Mama could think about was hay and laundry? And the racket that goose made—it’s a wonder one of them hadn’t crept downstairs in the wee hours and put it out of its misery. Saturday could hear it in there now, barking louder than the gulls.

“Next time I call the ocean, I’ll ask it please not to encroach so far onto the property.”

“See that you do,” was Mama’s reply.

“Who’s normal now?” teased Peter.

“I’m still just me,” Saturday snapped. “The magic was in Thursday’s mirror.” That’s right—part of this devastation was Thursday’s doing, and she would have them know of it.

“You have a mirror?” asked Monday. Saturday wondered if her sister was regretting the talk they’d had earlier.

“Had,” said Saturday. “It wasn’t a looking glass like yours. Trix and I tried to see in it. It didn’t work. It didn’t do anything.”

“Except split the earth and fill it up with seawater,” said Erik.

“Well, yes, that.”

“Mirror,” said Peter. “That fancy silver one from the trunk this spring?”

“The mirror you hated and hid the moment you received it and never looked at again?” Papa clarified.

Saturday rolled her eyes. “Yes.”

“Wasn’t it a set with a brush?” asked Peter.

“Best keep that brush in a safe place,” Erik said to Papa.

Saturday opened her mouth to object to the insinuation that anything in her possession would be deemed unsafe, when the air filled with bright spots of sunlight and tinkling bells. Everyone stopped what they were about to say and involuntarily smiled as one at the sound. Even the gulls seemed to silence and wonder what new divine presence had manifested. Saturday could have sworn she smelled sugar on the briny breeze.

Monday was laughing.

It was odd that such a sound would present itself during such a stressful occasion, and from such an unlikely source, yet it was refreshing as candied lemons. Monday’s profile, backed by the sea and crashing waves with her iridescent skirts and gossamer hair swirling about her, would have made master artists weep if they’d known what a sight they were missing.

Saturday tried to look past that, tried to block out the sunshine and the happiness and the loveliness that dazzled so hard it made everyone forget, if just for half a moment, all their worries and pains. She tried to see Monday for who she was, and not just the pretty packaging. Trouble was, the beauty was both within and without; an integral part of her soul.

Saturday shaded her eyes from the brilliance. “What?” she asked, while the rest were still dumbstruck.

Monday lifted a slender arm to the eastern horizon, where the sea met the parting storm clouds in a thin line. As if realizing it had been noticed, the morning sun split through the gray cover, showering both Monday and the far horizon in light. A rainbow appeared, bold against the exiting darkness, framing a small, dark gray blur on the water. Perhaps there had been some miracles after all.

Peter squinted into the distance. “Is that a rock?”

“A tall tree,” guessed Papa.

Monday smiled, and the sun shone all the brighter in competition. “It’s Thursday.”

4

Sulfur and Stone

THE PRIVY CAVE stank of brimstone. More than usual, since Peregrine’s nose didn’t typically register the acrid smell anymore. The stones of the walls and floor took on an orange hue and began to perspire. Peregrine hiked up his skirt and hopped from foot to foot out through the archway, barely making it around a corner before a burst of flame engulfed the narrow stone hallway.

This particular alcove probably wasn’t the safest place to do one’s business, but Peregrine couldn’t beat the cleanup. The perpetual venting flares came with a decent enough warning and kept the place from smelling like anything worse than the usual sulfur and stone. He’d been singed a time or two, but it was worth it.

Peregrine swung his lantern and watched the shadows dance along the shimmering, uneven walls of the tunnel. He danced a jig with them, his skirt swirling around his legs as he stomped gleefully through Puddle Lake. Disturbing the water marred the reflection he didn’t care to see.

“Hello there, boy,” Peregrine said to Shaggy Dog in greeting. “Find any good treats today?”

Shaggy Dog said nothing, just like it always did. Peregrine patted the giant rock formation on its hind leg.

Leila had selected exactly the right target on which to perform her spell. The witch’s daughter and Peregrine had shared the same build and the same dark features—it would have required far more magic to curse some tiny, fair young thing into taking Leila’s place at the Top of the World so that she could escape her mother and the dragon who slept here.

But Leila (he realized now) was not capable of that level of magic, and so her curse had not completely transformed him, thank the gods. He’d retained his manhood, for all the good it did him here in the White Mountains, on a peak higher than time itself. Though his height remained the same, the line of his jaw had softened and his skin had paled, taking on a subtle olive shade. His muscles had thinned and corded, like a dancer’s, not surprising with all the climbing and exploring he did on top of all the housework . . . or whatever one called chores when one’s home was a great mountain of fire and ice.

Peregrine passed the mushroom forest and growled at the stone bear that met him there, peering down from the ceiling. Big Bear marked the spot where the air began to grow cool again. Peregrine stopped to don the boots he’d been carrying. He took the shawl from his waist, pulled it over his bare arms, and continued on with his thoughts. At least his thoughts were still his own.

He’d collected every mirror he found and hidden them away in a cave beyond the dragon. He’d learned to ignore crystals and reflecting pools as he encountered them. Over time, he’d become quite adept at not seeing the face that wasn’t his: the black eyes beneath arched eyebrows, or the silver-blue streak in the thick black hair that always fell to his elbows in the morning, no matter how many times he hacked it off with implements, enchanted and otherwise. He’d learned to wear skirts and speak in whispers. Peregrine had kept the witch at arm’s length enough to fall beneath her notice. After a while, those habits had come as naturally as breathing.

He had considered exposing the ruse to the witch, in those first days. He’d contemplated revealing himself and facing the witch’s wrath simply to end his imprisonment. But Peregrine never quite found himself ready to forfeit both his life and the dream of triumphantly returning to the world of men. Eventually, he’d grown to enjoy the puzzles that these caves provided him. He relished the idea that he would never age or die. He didn’t even mind the witch so much, on the days when her demon blood wasn’t running wild.

And then that nice young woodcutter had stolen the witch’s eyes and made Peregrine’s life so much easier.

The cave floor grew drier and more even beneath the soles of his shoes; his breath turned whiter than the walls. Inside the kitchen, Peregrine banked the smokeless fire and swapped out the steaming laundry pot with another he’d readied with that night’s supper. Betwixt—currently a very ugly dog with a rattlesnake’s tail—twitched in his sleep in response to the reduction in heat.

Peregrine smiled. Betwixt was the main reason he stayed.

Betwixt was a chimera who’d been captured by the witch long before Peregrine, so long ago that he remembered neither his name nor his original shape. While the witch held him captive he had no control over where and when and how he changed form, but he was always some creature betwixt one animal and another, so the moniker suited him. And as Betwixt had not cared overly much for Leila, Peregrine’s presence suited him as well.

Peregrine nudged the dogsnake with his foot.

“If you intend on waking me up before I’m ready, you’d better intend to share some of that stew as well,” Betwixt growled without opening his eyes. “And a bowl of water.”

“Absolutely!” Peregrine said cheerily. “I was hoping you’d taste the stew for me. The spider meat is fresh, but it’s possible the brownie bits have gone rancid. And some of the mushrooms might have had a touch of color on them . . . it was hard to see. But then, it always is in this place.”

“Pantry Surprise again already?”

“Waste not, want not,” Peregrine replied.

“I’ll choose ‘want not,’ thank you,” said Betwixt.

Peregrine laughed at the retort. When one was forced to stay in another’s company in a cave beyond time, it was best to keep the atmosphere jovial. Peregrine and Betwixt explored together, hunted together, and avoided the witch together as best they could. In the time of Peregrine’s imprisonment Betwixt had become his best friend and closest confidant. It was a rare bond Peregrine had shared with no one since his father.

Peregrine took up a dagger and set to chopping shards of icerock out of the wall. He collected them in a bowl fashioned from an old warrior’s helmet and set them nearer to the fire to melt. After the fourth or fifth shard chipped away, the dagger snapped. The blade flew across the room and landed behind a clump of pillarstones.

“Troll blade,” said Betwixt. “Shoddy workmanship.”

The dagger might have also been a thousand years old. “I’ll try to select a dwarf blade next time.” Forced to move on to another task, Peregrine lifted the laundry pot and dumped the dirty water into a runnel that led back down to the heart of the mountain. One by one, he began wringing the clothes out for drying. “I had a vision of her again last night.”

“You had a dream. Stop calling them ‘visions’ or I’ll start calling you ‘witch.’”

“Fine, I had a dream. Of Elodie.”

And what a lovely dream it was. They’d lived in a rose-covered cottage at the edge of the forest. A low rock wall surrounded a garden and a small barn. The kitchen had two ovens and a pantry and a pump house for well water. The bedroom had been up a long flight of stairs that reminded Peregrine of one of the turrets at Starburn, but he had never seen this place before. He only knew that he was warm and safe and loved and that she was there, smiling at him over the dinner table. The light from the sun twinkled in her bright eyes and caught her hair and turned it gold.

“Or not,” said Betwixt. “You can’t be sure it’s her. You haven’t seen her since you were small children.”

“You’re such a killjoy.” Peregrine slapped the witch’s ratty dress against the side of the cauldron and wrung it out in frustration.

Betwixt sighed and gave in. He was too kind to demean any visions of loveliness, however fleeting, insubstantial, and wholly untrue. “Go on. Tell me about her.”

Peregrine nodded. “I see her as a goddess wrapped in waves of blue-green sea, or a terrible angel in a white gown sullied with blood, rising like the moon above a battlefield. Sometimes she holds a sword in one hand, sometimes an ax. Day or night, rain or shine, there is always a wind in her long golden hair and a fire in her bright eyes.” Peregrine sobered and moved on to the next item of laundry—it fell to pieces as he lifted it. He flung the rent fabric into the pile he used for torch rags. “I am a fool for getting myself cursed on the way to fetch her.”

“You can’t keep torturing yourself,” said Betwixt. “If the circumstances had been different, who knows what might have happened. If Leila had encountered you together, you or Elodie might have come to harm.”

“I might have fought back. Or declined her accursed wish.” Oh, all the things he might have done then. He’d gone over each scenario in his mind, futilely weighing his chances of success and defeat. “But you don’t think the woman I’m seeing is Elodie? I don’t see how it can’t be. I don’t know any other women.” Except the witch, her daughter, and some chamber and scullery maids he recalled as a child.

“Peregrine.” That name was never uttered in the company of the witch. The chimera used it now to get his attention, and he had it. “You were an earl’s son betrothed to a towheaded little girl with pigtails. The woman you’re envisioning might be Elodie fully grown, but she might just as easily be one of those goddesses you’re always praying to, or a figment born of desperation and Earthfire fumes. I just wish you would stop using her to regret your past. Fact or fiction, she wouldn’t want that. I don’t think the real Elodie would want that either.”

“You’re right.” But saying the words did not dispel the guilt he would forever feel for disappearing before he’d even had the chance to get to know his betrothed. He wondered if Elodie ever thought about him, or if she still waited for him. He wondered if she hated the idea of an arranged partnership, or if it would have afforded her the same freedom it had him. He wondered if similar visions haunted her sleep. Sweet Elodie. He would return to her one day, when he had learned all there was to learn. When he was worthy of her. For now, he would settle for visiting her in his dreams.

“Stop it,” said Betwixt.

“What?”

“You’re beating yourself up again! I can tell by the look on your face. She’s a dream. Let her fade into memory like dreams are supposed to.”

Peregrine stuck his tongue out at the dogsnake. Betwixt could decide what that facial expression meant.

“If Elodie of Cassot still thinks of you at all, I’m sure she feels what the rest of us do: pity that you never had a chance to live your life once it finally belonged to you.”

Peregrine’s childhood had been consumed with caring for an ill father, so he’d never enjoyed a life outside his family estate. Elodie embodied everything that might have been. “She was the only thing I was ever responsible for, and I let her slip through my fingers.”

“So go back to her. The mountain is waiting.”

“Waiting to kill me,” said Peregrine. “If it had been that easy, I would have left long ago.”

Betwixt swatted at Peregrine with his tail. He wandered to an opaque section of the wall where calcite had dripped down long ago in rippled lines and scratched his back against it. “You didn’t exactly have a choice. You got cursed, remember?”

“How could I forget?” Enough of this folly; it was time to lighten the mood. “But if I hadn’t been cursed I never would have met you, my dearest friend.”

“That would have been a pity,” Betwixt agreed, and they chuckled in unison.

Neither was ready when the first tremor struck.

Startled and confused by the sudden sense of vertigo, Peregrine lost his footing. Betwixt—fully awake now—snapped the sleeve of Peregrine’s shirt between his massive jaws and dragged him away from the fire. Peregrine huddled with Betwixt in a small archway. The mountain shivered beneath him. Fingers of icerock that had pointed down from the ceiling now joined them on the floor. Some crushed the pillarstones that grew up from the ground, splintering into white shards and glittering dust. Crystalline protrusions rang out like church bells as they crashed. Mighty columns that were created with the mountain toppled and fell. The air grew thick with ice and chalk. Peregrine coughed and hoped that slow, molten Earthfire was not soon to follow. Betwixt howled, his tail rattling madly.

“Dragon?” Peregrine yelled to Betwixt over the thunder of the cave. “Could it be?”

Happily, Betwixt’s canine hearing had not been compromised. “If so, it’s been lovely knowing you,” said the chimera.

The thought of death had once given Peregrine a great sense of relief. Now he prayed to gods unknown to preserve his meager life, pretense and all.

After what felt like a lifetime, the vibrations dulled like a forgotten note on a harpsichord and the caves wrapped themselves once more in a shroud of cold, dark silence. Peregrine shook debris out of his hair. He was unhurt. In the dim light of the dust-covered fire he examined Betwixt from head to toe, giving his unscathed friend a hearty pat on the hindquarters in both reassurance and gratitude. He retrieved the overturned lantern, all the while silently counting to himself. Shortly thereafter, the shrieking started.

“Thirteen seconds,” he said to Betwixt. “She must have been knocked unconscious.”

Betwixt huffed, sneezed, and rattled his tail for good meas-ure. He pointedly ignored the banshee wail, returning instead to the fire and nosing rocky debris from his former spot there. The screeching began to resolve itself out of the echoes.

“HE’S ALIVE!”

The witch’s familiar burst out from behind a still-standing column, a flurry of black wings. Cwyn’s usual perch had been upset by the quaking, so she flew once around the room and landed on Betwixt’s giant head. The chimera snapped at the mischievous raven.