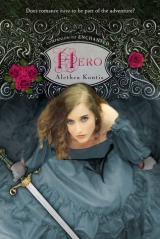

Текст книги "Hero"

Автор книги: Alethea Kontis

Соавторы: Alethea Kontis

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

7

Welcome to the Madness

THE AIR tasted like the kitchen in winter, all frost and cinders. Her coverlet was rough in patches. She was excessively warm. Saturday opened her eyes and tried to focus on the stone blocks in the ceiling of her tower room. Had Papa let her sleep past dawn again?

And then the shrieking began.

Saturday sat up and put her hand on the hilt of her sword. The very warm lump on the pallet beside her cursed, and from the blankets jumped either a very handsome girl or a very pretty boy in a skirt. Not a nightgown, a skirt. What sort of person wore a skirt to bed? And what was he . . . she doing in Saturday’s room?

But she wasn’t supposed to be in her room either. She should have been with Mama on Thursday’s ship. Room . . . sea . . . ship . . . Saturday blinked as memories swam before her.

“She’s awake early.”

“She” seemed to designate someone other than Saturday. The strange boy cursed again. He . . . she . . . took Saturday by the shoulders and shook her, forcing her to concentrate on . . . his, definitely his . . . maybe . . . face. Either his skin was slightly green or Saturday was sicker than she felt. “Doesn’t matter. It’s my fault. Look, I’m sorry I don’t have time to explain. Just don’t say anything. If you don’t say anything, you will stay safe. Can you promise me that?”

Saturday was too confused to do anything but nod. She’d promised Peter that she’d find Trix and come home. She had promised to protect Mama and then vanished without a word to her. She didn’t seem to be very good at promises lately.

“Good girl.” The strange boy kissed her forehead. “Welcome to the madness.” He leapt from her bedside to the far side of the circle of stones in the middle of the room.

Circle of stones. White, glittering rocks. Definitely not her room.

The strange boy dumped half a bin of coal into the stone circle—only the very rich could afford to waste coal like that—and haphazardly stirred it with a poker. The room warmed and brightened bit by bit, though there was no smoke from the fire. The pit smelled of brimstone. Perhaps she’d gone to Hell and the raven who’d captured her was an angel delivering her to Lord Death.

The boy straightened his shirt and skirt. He wound his long black hair back into a knot and fixed it at the base of his skull. Friday had that same talent; Saturday had watched her sister do it enough times before starting the mending at the kitchen table. Her hand drifted to her own hair, grasping at nothing but air until it came to her chin. A vision flashed in her mind of Erik . . . the slice of a sword . . . a battle cry. At the same time, the light from the fresh coals began to fully illuminate the space around them.

Above her, undulating, milky-white stone spilled down from the heavens. The ceiling lifted like a wild cathedral over archways and crevasses and up again into empty shadows. Giant protrusions stretched down from above or up from below, reaching in to fill the space with curious waxen fingers. This was no palace but a cave, one as old as the gods, or older.

“Where are we?”

The strange boy shushed her. She remembered his advice about staying safe and closed her mouth.

Before the vapor of her breath could dissipate, an enormous, long-tusked crimson beetle-thing came scuttling around the corner on . . . chicken legs? Right on his wickedly pointed tail flew a large bird with deeply violet wings. Behind the bird stalked a small, wraithlike woman with giant empty holes where her eyes should be. Her skin was slightly blue, though she didn’t appear cold.

Madness, the boy had said. Oh, how right he had been.

Saturday was instantly on her feet with her sword in both hands.

“Forgive me, Mother, I did not expect you up and around for some time. That spell took a lot out of you.” The boy gave the crimson insect a look that Saturday might have given Peter, if he hadn’t woken her in time for breakfast.

Wait . . . had he called her Mother? But the boy wasn’t blue. And spells? She was no fairy, so that meant this wraith was a sorceress or a witch. Judging by her hue and the small horns on her forehead, Saturday guessed the latter. What had become of her eyes?

The witch ignored the boy and pointed a bony finger at Saturday. “How dare you mess with my familiar! Who ever heard of a purple raven?” Those terribly empty eye sockets gaped accusingly in Saturday’s direction, but slightly to the left, as if there were someone standing behind her. The effect was unnerving. Saturday resisted the urge to turn and look. “I’ll take that sword, dearie.”

Over my dead body. Saturday stretched the fingers of both hands, wrapped them tightly around the hilt again, and settled into a defensive position on the pallet. She sized the witch up. The insane old woman was no physical match for her. If she attacked before the witch could loose a spell, the fight would be over and done with quickly. Then Saturday could give her full attention to getting out of this bizarre cavern and back to the swordfight from which she’d been so rudely kidnapped.

“There’s no escape from here this time, my terrible troublemaker. Hand it over.”

This time? Saturday had never been to this place before. She definitely would have remembered.

“Just take it, Mother. Use your magic,” said the boy.

Saturday scowled. So much for thinking the boy was on her side. Saturday calculated the distances in the room, deciding how close the witch would need to come to her before she could spring her attack.

“Snip-snap-snurre-basselure—I can’t grab hold of it! There’s something protecting her.”

There was?

“You take the sword,” the witch told the boy. “You’re about his size.”

His? Saturday did turn then to see if someone really was standing behind her, but there was no one else in the room. She turned back to the witch . . . and was treated to a face full of violet feathers. Saturday spat and swung but the bird was too close; the weight of the sword shifted her off balance. She kicked the furs aside and the raven-that-should-not-have-been-purple came at her again. Saturday gritted her teeth and growled, as a battle cry would have left her with another mouthful of feathers.

Stop fighting. Give her the sword.

Saturday stopped fighting, but only because THERE WAS A VOICE IN HER HEAD. A voice coming from inside one’s own skull was not something a fighter trained for. Then again, it was exactly the sort of stunt she would have expected Velius to pull.

You’re going to think yourself into an early grave, girl.

“Who—?” The boy moved closer and she remembered to keep her mouth shut.

He stretched out a hand. “Woodcutter, please.”

He knew her name? Her suspicions grew. This was no random abduction. Did they plan to ransom her back to Sunday and Rumbold? Not without shedding a few drops of blood first. Saturday wouldn’t make this kidnapping easy on anyone.

NOW, CHILD.

The words echoed so loudly between her ears that she winced and loosened her grip on the sword.

GET OUT OF MY HEAD, Saturday thought back, but it was too late. The boy plucked the sword from her grasp and the air began to sing. As if burned, he quickly dropped the weapon onto the pallet.

“It’s hot!” he cried.

Saturday cocked her head at the bold-faced lie. She recognized that strange singing—it was the same sound her nameday gift had made in her hands the night it had changed from an ax to a sword. The boy knew her sword was enchanted and, for whatever reason, he did not want the empty-eyed wraith touching it.

“Charmed,” said the witch. “Ooh, how wonderful! Back up, sweetling, and let Mummy take care of it.” She crossed the room as efficiently as anyone with sight, then knelt and gingerly swaddled the sword inside the fur blankets without touching any part of the hilt or blade.

Saturday lunged for the witch with her dagger. The witch held up a blue-palmed hand and Saturday froze in mid-strike. She strained with all her might, but not so much as a finger moved. She tried to cry out, but the sound died in her throat.

The witch clasped the sword to her skinny chest and strutted out of the cave with all the confidence of a woman who had two very good eyes. “Come, Cwyn,” she said to the bird. “Betwixt, please sit on our guest until we return,” she said in the direction of the bugaboo. “I’ll deal with you later, Jack Woodcutter,” she said to the space beside Saturday’s head, and then cackled madly on her way out of the cave.

Jack? The witch thought she was her dead brother? Had these people lost their minds, or had she?

Saturday shook her head to clear the cobwebs, happy to find that she was able to move again now that the wraith and her bird had left the area. The next body part she freed was her index finger, which she pointed at the boy.

“You,” she commanded with a voice not unlike her mother’s, “will tell me exactly where I am and what is going on. And you”—she pointed at the bugaboo—“if you so much as attempt to sit on me, I will throw you out the nearest window.” If there weren’t any windows in these caves, Saturday would make one. “And then I will sit on you.”

The bugaboo shook its tusks, and his carapace turned a light shade of ocean blue.

“Did you just . . . ? Gods, I am not colorful enough for this crowd.”

“His name is Betwixt,” said the boy.

“Betwixt. I’d say I’m pleased to meet you, but this is all a bit too strange for me. And if you know my family, that’s saying a lot.” Betwixt’s shell shimmered and changed again. “What’s green mean?” Saturday asked the boy.

“Not sure, but I think he’s in love with you.”

“Huh. So no crushing me with your massive bulk.” Betwixt waved his tusks back and forth in dissent. “Excellent. Your turn.” Saturday raised her eyebrows at the boy.

“What do you want to know first: my story, or your brother’s?”

“Do you know where Trix is?”

“Who’s Trix?” asked the boy.

“Not the brother you were referring to, apparently,” said Saturday.

“Jack,” he said loudly and slowly. “Do you want me to tell you about Jack?”

“Sum up whatever you can fit in before the witch returns, or I punch you.” Saturday raised her fists. “I may just punch you anyway, for good measure. I’m not big on patience.”

The boy took a deep breath and then spoke as fast as he could. “The witch is a lorelei—a water demon. She’s not very talented when it comes to spells, so she siphons magic off a sleeping dragon in an effort to open a doorway back to the demon home world. Her daughter, Leila, ran away after cursing some fool with similar features to take her place.” He curtseyed. “The witch sees through the eyes of Cwyn, her raven familiar, because her eyes were stolen by one evil, conniving Jack Woodcutter in an effort to thwart her spellcasting.” The boy crossed his arms over his chest. “The end.”

Saturday hailed from a family of storytellers, but this tale bordered on preposterous. “Where am I?”

“The Top of the World.”

“And you are . . . ?”

The boy curtseyed again, and then bowed. “Peregrine of Starburn. Cursed on the way to fetch his betrothed.”

Saturday couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to marry this fop. “But the witch thinks that you are her daughter.”

“Leila. Yes.”

“And she thinks that I am my brother?”

“I saw the family resemblance right away. So which day of the week does that make you?”

Oh, how she wanted to punch the self-serving grin right off his face. “Saturday.”

“Splendid!”

Saturday’s clenched fists itched. She was trapped on top of the highest mountain in the world, without her sword. The situation had all the earmarks of a Jack-worthy adventure, but she didn’t see anything particularly splendid about any of it. “Where is she taking my sword?”

“To her bedchambers, most likely.”

“I’ll just go and find it, then,” said Saturday.

“It won’t be that easy,” said the boy. “She stays there most of the time. When she’s not sleeping she’s casting spells. Or preparing for spells. Or generally making a mess of everything.”

Saturday harrumphed. Next to swinging a sharp weapon and scowling, it was one of the things she did best.

“Did Jack tell you about this place?” the boy—Peregrine—asked.

Saturday wavered between anger and jealousy. “You’ve seen my brother more recently than I have.” She chose not to be more specific.

When she was but a toddler, Jack Junior had been cursed by an evil fairy and turned into a dog at the palace in Arilland, then subsequently presumed dead. Earlier in the year, when Sunday had rescued Prince Rumbold from his own curse, it was revealed to the family that Jack had not died, but in fact had gone off to live a full and adventurous life until he’d been eaten by a wolf. Or not. Sunday believed Jack was still alive. Saturday didn’t know what was true anymore. As a result, she abhorred secrets about as much as this conversation.

“I should go. The witch will be back soon to assign your impossible tasks. There might be as many as three. You will have to complete them unless you can tell her where you’ve hidden her eyes.”

“But I don’t know, because I’m not Jack.”

Peregrine snapped his fingers. “Got it in one. And if you know what’s good for you, you won’t tell her you’re not who she thinks you are.” He shook out his skirt, picked up a lantern, and began walking away. “Up here, no one can hear you scream.”

“Wait . . . so what am I supposed to call you? Leila, right?”

“If you have to, refer to me as ‘the maid,’ but it’s really best if you don’t say anything at all.” He turned back to add, “I’ll try to help you when I can. Just ask.” The bugaboo followed him out through the archway.

He’d left before telling her anything else, like where to find a drink of water, or breakfast, or where to relieve and wash herself. It would have been nice to have her messenger bag with everything she’d prepared for a journey like this. If she ever got it back it would never leave her side, even on a place as theoretically secure as her sister’s ship.

Well, she’d just have to go exploring in the caves before the witch found her. She would find a way out of this place or die trying—if Jack had found a way out, she could too. Gods knew what sort of trouble Trix would be in by now. If he were still alive. She had to believe he was. But the sheer size of that ocean . . .

Saturday’s heart ached in her chest. Perhaps this prison was the gods’ way of punishing her for breaking the world.

She stepped off the pallet where she’d been standing onto the uneven stone floor and a chill raced up through her bones. She hadn’t remembered removing her boots . . . or her swordbelt . . . or changing her clothes. The shirt and trousers she wore now were old, but not ill-fitting. She found her boots resting beside the stone pit. There did not seem to be another lantern handy, so she removed one of the small torches from the wall and used the fire to light it.

Saturday had a measure of experience with dark mazes. She’d been lost in the Wood many times—more frequently as a little girl than now. It happened to every woodcutter from time to time, even Papa. No one but the piskies knew their way around the Wood.

This cavern was nothing like the Wood at all.

Within minutes, Saturday’s head ached from her eyes’ constant refocusing. The icerock walls with their odd patterns confused her, robbing her of her depth perception. The shadows played tricks on her, sometimes revealing a dead end, other times leading Saturday to chasms down which she might fall forever.

Every time the light moved, the cave changed. Around one corner was a forest of trees, hundreds of them, completely encased in snow and dripping with icicles, frozen into a timeless winter. They even smelled of damp cold. Stone faces stared at her from the shadows. Stone icicles rimmed the caverns like bared teeth protecting unknown treasures.

Making rock piles to mark her path in this space would have been futile; there were so many pillared protrusions, tall and knobby and many looking like broken rock piles themselves, that she didn’t bother. She took out her dagger and scratched the walls in a few places, two straight cuts, angled inward to look like her mother’s discerning brow, but from even a few paces away they disappeared into the sheets of white and ice and crystal.

Saturday banged her head for the umpteenth time. No matter what the stories said, caves were meant for dwarves, not giants. Having her sword would have at least helped with the massive headache she’d developed—foul witch. She rested beside a steep drop-off and something dripped onto her. Water cascaded down from the ceiling; she turned her head up to catch the water in her parched mouth. The air had gotten warmer, but rain? Inside? What a curious thing!

She stretched out her arm over the chasm in an effort to keep her balance and was surprised to see two torches casting shadows.

“Why, you’re not a chasm at all, are you?” Her voice did not echo like she thought it might in a maze this size.

Saturday dipped a boot in the mirage and discovered that naught but a shallow pool of water had cast the massive reflection. Laughing, she leaned over the rock on which she sat and prepared to drink.

A stranger’s face looked back at her.

All her life, it had never occurred to Saturday to cut her hair. Girls had long hair and boys had short hair, and that was just the way of the world. She tied it up when she was in the Wood or tucked it under a cap before sword practice and never thought twice about it. Her golden locks were gone now, close cropped at the nape of her neck, while the longer tendrils by her face dipped their ends in the pool. She couldn’t be sure exactly how much she looked like Jack, but it wasn’t the first time she’d been mistaken for a boy.

Saturday stuck her face in the pool and drank deeply. The water tasted of grit and soot. When she’d had her fill, she raised the torch again and moved on through the stone forest.

Oh, what stories Sunday would have told about these decorated monoliths, sparkling in the lantern light, frowning down upon her with their protruding, frostbitten brows. Friday would have imagined the icicles as rows of needles standing at attention among yards and yards of lace. Thursday would have seen the history of these caves through her spyglass, back to when this mountain was nothing but a rolling hill in the landscape. Wednesday most likely would have recited poetry to the dancing shadows, stumbling across a spell or two by design or by accident before growing thick wings and flying herself to safety. Saturday wished she had such wings. The lantern showed them everywhere now, twin peaks of shadow feathers mocking her with their insubstantiality.

One of the shadows flew straight up and slapped her in the face with warm feathers. Saturday recognized that smell. The witch’s familiar had found her.

“Silly troublemaker. Were you trying to escape again? I’ve blocked this way, as you can see.”

Saturday saw no such thing, nor could she see the witch. She held the torch back, squinting into the darkness until she made out the soft light of a stone bracelet infused with magic. In the hand of the skinny arm that wore the circle of light was a long-handled rake with rusted tines.

Saturday subtly pushed the blue-green fabric of her own humble bracelet under her sleeve. Out of raven-sight, out of mind. The witch had taken her sword; she wouldn’t part with this last memento so easily.

“I have your first task.” The witch giggled and cackled with pride.

“I’m ready,” said Saturday.

“Ha!” shrieked the witch. “You think you’re going to sweep the stones or empty the water pots or tame the basilisk? The tasks I set were all too easy the first time.”

“You have new pets?” Saturday guessed.

“No more pets. Tired of them. Killed them and ate them. Slow-roasted them over the fire while they died screaming. They were best that way.” The witch licked her lips, and the raven fluttered restlessly.

“You’re worrying the bird,” said Saturday.

“Cwyn is not my pet. She is my familiar. She serves as my eyes, until you find them. And now you will clean her nest.”

Saturday took the rake the witch thrust at her. Clean the nest of a single bird? How was that harder than taming a basilisk? But Saturday remembered the strange boy Peregrine’s advice and kept her mouth shut lest the witch come up with something more difficult. “Lead on,” she said. “It seems I don’t know my way around these caves as well as I once did.”

“That’s because the ways of these caves are not your ways. They are my ways, and I change them as I will.” The witch threw her arms open toward the false lake and the wall of rocks beyond it. “Here we are!”

The witch ducked through an archway into a small alcove filled with stone pillars and outcroppings. Beneath them, on the patch of somewhat-level floor, was a small amount of dried moss. Saturday wrinkled her nose at the smell, reminiscent of the chickens at home. Why did birds stink worse than horses and cows?

“So, if I clean this up, you’ll give me my sword back?” asked Saturday.

“If you clean this up, you get to keep your life,” answered the witch. “Think, while you work, about where you put my eyes. You will find them, and find them soon, or I will take yours instead. Snip-snap-snurre-basselure!”