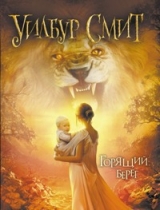

Текст книги "The Burning Shore"

Автор книги: Wilbur Smith

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

I'm sure I saw something. She stared about her. But it's gone now. She changed Shasa to her other hip.

What a big lump you are becoming! But never mind, we'll be there soon. She started forward again, and the trees thinned out and Centaine found herself at the head of another long open glade. The moonlight laid a pale metallic sheen on the short grass.

Eagerly she surveyed the open ground, focusing her attention on each dark irregularity, hoping to see hobbled horses near a smouldering fire and human shaped rolled into their blankets, but the shapes were only tree stumps or anthills, and at the far side of the glade a small herd of wildebeest grazing heads down.

Don't worry, Shasa, she spoke louder to cover her own intense disappointment, I'm sure they'll be camped in the trees. The wildebeest threw up their heads and erupted into a rumbling snorting stampede, streaming away into the trees, fine dust hanging behind them like mist.

What frightened them, Shasa? The wind is with us, they could not have taken our scent. The sound of the running herd dwindled. Something chased them! She looked around her carefully. I'm imagining things.

I'm seeing things that aren't there. We mustn't start panicking at shadows. Centaine started forward firmly, but within a short distance she stopped again fearfully.

Did you hear that, Shasa? There is something following us. I heard the footfalls, but it's stopped now. It's watching us, I can feel it. At that moment a small cloud passed over the moon and the world turned dark.

The moon will come out again soon. Centaine hugged the infant so hard that Shasa gave a little bleat of protest. I'm sorry, baby. She relaxed her grip and then stumbled as she started forward.

I wish we hadn't come, no, that's not true. We had to come. We must be brave, Shasa. We can't follow the spoor without the moon. She sank down to rest, looking up into the sky. The moon was a pale nimbus through the thin gunmetal cloud, and then it broke out into a hole in the cloud layer and for a moment flooded the glade with soft platinum light.

Shasa! Centaine's voice rose into a high thin Scream.

There was something out there, a huge pate shape, as big as a horse, but with sinister, stealthy, unhorselike carriage. At her cry, it sank out of sight below the tops of the grass.

Centaine leapt to her feet and raced towards the trees, but before she reached them the moon was snuffed out again, and in the darkness Centaine fell full length. Shasa waited fretfully against her chest.

Please be quiet, baby. Centaine hugged him, but the child sensed her terror and screamed. Don't, Shasa. You'll bring it after us. Centaine was trembling wildly. That big pale thing out there in the darkness was possessed of an unearthly menace, a palpable aura of evil, and she knew what it was. She had seen it before.

She pressed herself flat to the earth, trying to cover Shasa with her own body. Then there was a sound, a hurricane of sound that filled the night, filled her head seemed to fill her very soul. She had heard that sound before, but never so close, never so soul-shattering.

Oh, sweet mother of God, she whispered. It was the full-blooded roar of a lion. The most terrifying sound of the African wilds.

At that moment, the moon broke out of the cloud again, and she saw the lion clearly. It stood facing her, fifty paces away, and it was immense, with its mane fully extended, a peacock's tail of ruddy hair around the massive flat head.

Its tail swung from side to side, flicking the black tuft like a metronome, and then it extended its neck and humped its shoulders, lowering and opening its jaws so that the long ivory fangs gleamed in the moonlight like daggers, and it roared again.

All the ferocity and cruelty of Africa seemed to be distilled into that dreadful blast. Though she had read the descriptions of the travellers and hunters, they could not prepare her for the actuality. The blast seemed to crush her chest, so that her heart checked and her lungs seized.

It loosened her bowels and her bladder so she had to clench fiercely to keep control of herself. In her arms Shasa screeched and wriggled, and that was enough to jar Centaine out of her paroxysm of terror.

The lion was an old red torn, an outcast from the pride.

His teeth and claws were worn, his skin scarred and almost bald across the shoulders. In the succession battle with the young prime male who had driven him from the pride, he had lost one eye, a hooked claw had ripped it from the socket.

He was sick and starving, his ribs racked out under his scraggy hide, and in his hunger he had attacked a porcupine three days before. A dozen long poisonous barbed quills had driven deeply into his neck and cheeks and were already suppurating and festering. He was old and weak and uncertain, his confidence shattered, and he was wary of man and the man odour. His ancestral memories, his own long experience had warned him to stay clear of these strange frail upright creatures. His roarings were symptoms of his nervousness and uncertainty. There was a time when, as hungry as he was now, he would have gone in swiftly and silently. Even now his jaws had the strength to crunch through a skull or thighbone and a single blow of one massive forepaw could shatter a man's spine. However, he hung back, circling the prey. Perhaps, if there had been no moon, he would have been bolder, or if he had ever eaten human flesh before, or if the agony of the buried quills had been less crippling, but now he roared indecisively. Centaine leaped to her feet. It was instinctive. She had watched the old black stable torn cat at Mort Homme with a mouse, and his reflex action to his victim's attempted flight. Somehow she knew that to run would be to bring the great cat down on her immediately.

She screamed, -and holding the pointed stave high, she rushed straight at the lion. He whirled and galloped off through the grass, fifty paces, and then stopped and looked back at her, lashing his tail from side to side, and he growled with frustration.

Still facing him, clutching Shasa under one arm and the stave in the other hand, Centaine backed away. She glanced over her shoulder, the nearest mopani tree stood isolated from the rest of the forest. It was straight and sturdy with a fork high above the ground, but it seemed to be at the other end of the earth from where she stood.

We mustn't run, Shasa, she whispered, and her voice shook. Slowly. Slowly, now. Her sweat was running into her eyes though she shivered wildly with cold and terror.

The lion circled around towards the forest, swinging its head low, ears pricked, and she saw the gleam of his single eye like the flash of a knife-blade.

We must get to the tree, Shasa, and the infant whined and kicked on her hip. The lion stopped and she could hear it sniffing.

Oh God, it's so big. Her foot caught and she almost fell. The lion rushed forward, grunting terrible exhalations of sound, like the pistons of a locomotive, and she screamed and waved the stave.

The lion stopped, but this time stood its ground, facing her, lowering its great shaggy head threateningly and lashing the long, black-tipped tail, and when Centaine began to back away, it moved forward, slinking low to the earth. The tree, Shasa, we must reach the tree! The lion started to circle again, and Centaine glanced up at the moon. There was another dark blot of cloud trundling down from the north.

Please don't cover the moon! she whispered brokenly.

She realized how their lives depended on that soft uncertain light, she instinctively knew how bold the great cat would become in darkness. Even now its circles were becoming narrower, it was working in, still cautious and wary, but watching her and perhaps beginning to realize how utterly helpless she was. The final killing charge was only seconds away.

Something hit her from behind and she shrieked and almost fell, before she realized that she had walked backwards into the base of the mopani tree. She clung to it for support, for her legs could not hold her, so intense was her relief.

Shaking so much that she almost dropped it, she unslung the leather satchel from her shoulder and tipped the ostrich-egg bottles out of it. Then she pushed Shasa feet first into the bag, so only his head protruded, and slung him over her back. Shasa was redfaced and yelling angrily.

Be quiet, please be quiet– She snatched up her stave again, and stuck it into her rope belt like a sword. She d to catch the first branch above her head and she jumped got a hold and scrambled with her bare feet for a grip on the rough bark. She would never have believed it possible, but in desperation she found untapped reserves and she hauled herself and her load upwards by the main strength of arms and legs, and crawled on to the branch.

Still, she was only five feet above the ground, and the lion grunted fearsomely and made a short rush forward.

She teetered on the branch and reached up for another hold, and then another. The bark was rough and abrasive as crocodile skin and her fingers and shins were bleeding by the time she scrambled into the fork of the mopani thirty feet above the ground.

The lion smelled the blood from her grazed skin and it drove him frantic with hunger. He roared and prowled around the base of the mopani stopping to sniff at the ostrich eggs that Centaine had dropped, and then roaring again.

We are safe, Shasa, Centaine was sobbing with relief, crouched in the high fork, holding the child on her lap and peering down through the leaves and branches on to the broad muscled back of the old lion. She realised that she could see more clearly, the light of dawn was flushing the eastern sky. She could clearly make out that the great cat was a gingery reddish colour, and unlike the drawings she had seen, his mane was not black but the same ruddy colour.

O'wa called them red devils, she remembered, hugging Shasa and trying to still his outraged yells. How long until it's light? She looked anxiously to the east and saw the dawn coming in a splendour of molten copper and furnace reds.

It will be day soon, Shasa, she told him. Then the beast will go away– Below her the lion reared up on its hindlegs and stood against the trunk, looking up at her.

One eye, he's only got one eye. The black scarred socket somehow made the other glowing yellow eye more murderous, and Centaine shuddered wildly.

The lion ripped at the trunk of the tree with the claws of both front feet, erupting into those terrible crackling roars once more. It ripped slabs and long shreds of bark from the trunk, leaving wet wounds weeping with sap.

Go away! Centaine screamed at it, and the lion gathered itself on its hindquarters and launched itself upwards, hooking with all four feet.

No! Go away! Michael had told her and she had read in Levaillant that lions did not climb trees, but this great red cat came swarming up the trunk and then pulled itself on to the main branch ten feet above the ground and balanced there staring up at her.

Shasa! She realized then that the lion was going to get her, her climb had merely delayed the moment. We've got to save you, Shasa. She dragged herself upward, standing in the fork, and clutching the side branch.

There! Above her head there was a broken branch that stuck out like a hatpeg, and using all that remained of her strength, she lifted the rawhide bag with Shasa in it and hooked the strap over the peg.

Goodbye, my darling, she panted. Perhaps H'ani will find you. Shasa was struggling and kicking, the bag swung and twisted, and Centaine sank back on to the fork and drew the sharpened stave from her belt. Be still, baby, please be still. She did not look up at him. She was watching the lion below her. If you are A quiet it might not see you, it might be satisfied. The lion stretched up with its forelegs, balancing on the branch, and roared again. She smelt it now, the stink of its festering wounds and the dead carrion reek of its breath, and then the beast hurled itself upwards.

With claws ripping the bark, clinging with all four paws, it came up in a series of convulsive leaps. Its head I was thrown back, its single yellow eye fastened on Centaine, and with those monstrous explosions of sound bursting up out of its gaping pink jaws, it came straight i at her.

Centaine screamed and drove the point of her stave down into the jaws with all her strength. She felt the sharpened end bite into the soft pink mucus membrane in the back of its throat, saw the spurt of scarlet blood, and then the lion locked its jaws on the stave and with a toss of its flying mane ripped it out of her hands and sent it windmilling out and down to hit the earth below.

Then with bright blood streaming from its jaws, blowing a pink cloud every time it roared, the lion reached up with one huge paw.

Centaine jack-knifed her legs upwards, trying to avoid it, but she was not quick enough; one of the curled yellow claws, as long and thick as a man's forefinger, sank into her flesh above her bare ankle, and she was jerked savagely downwards.

As she was pulled out of the fork, she flung both her arms around the side branch and with all her remaining strength she held on. She felt her whole body racked, drawn out, the unbearable weight of the lion stretching her leg until she felt her knee and hip joint crack, and pain shot up her spine and filled her skull like a bursting sky rocket.

She felt the lion's claw curling in her flesh, and her arms started to give way. Inch by inch she was drawn out of the tree.

Look after my baby, she screamed. Please God, protect my baby.

It was another wild-goose chase, Garry was absolutely convinced of it, though of course he would never be foolhardy enough to say so. Even the thought made him feel guilty, and he glanced sideways at the woman he loved.

Anna had learned English and lost a little weight in the eighteen short sweet months since he had met her, and the latter was the only circumstance in his life he would have altered if it had been in his power, indeed he was always urging food upon her. There was a German pitisserie and confectioner's opposite the Kaiserhof Hotel in Windhoek where Garry had taken a permanent suite. He never passed the shop without going in to buy a box of the marvelous black chocolates or a creamy cake, Black Forest Cherry Cake was a favourite, which he took back to Anna. When he carved, he always reserved the fattest, juiciest cuts for her, and replenished the plate without allowing her time to protest. However, she had still lost weight.

They didn't spend enough time in the hotel suite, he brooded. They spent too much of their time chasing about the bush, as they were doing now. No sooner had he put a few pounds on her than they were off again, banging and jolting over remote tracks in the open Fiat tourer that had replaced the T model Ford, or when the tracks faded, resorting to horses and mules to carry them over rugged ranges of mountains or through the yawning canyons and rock deserts of the interior, chasing the will-o'-the-wisp of rumour and chance and often of deliberately misleading information.

The crazy old people, Die twee ou onbeskofters that was the title which they have gained themselves from one end of the territory to the other, and Garry took a perverse and defiant pleasure in the fact that he had earned it the hard way. When he had totted up the actual cost in hard cash of the continuing search, he had been utterly appalled, until suddenly he had thought, What else have I got to spend it on anyway, except Anna? And then, after a little further reflection, What else is there except Anna? And with that discovery he had thrown himself headlong into the madness.

Of course, sometimes when he woke in the night and thought about it clearly and sensibly, he knew that his grandson did not exist, he knew that the daughter-in-law that he had never seen had drowned eighteen months ago, out there in the cold green waters of the Atlantic, taking with her the last contact he could ever have with Michael.

Then that terrible sorrow came upon him once again, threatening to crush him, until he groped for Anna in the bed beside him and crept to her, and even in her sleep she seemed to sense his need and she would roll towards him and take him to her.

Then in the morning he awoke refreshed and revitalized, logic banished and blind faith restored, ready to set out on the next fantastic adventure that awaited them.

Garry had arranged for five thousand posters to be printed in Cape Town, and distributed to every police station, magistrate's court, post office and railway station in South West Africa. Wherever he and Anna travelled, there was always a bundle of posters on the back seat of the Fiat or in one of the saddle-bags, and they stuck them SIO on every blank wall of every general dealer's or barroom they passed, they nailed them to tree trunks at desolate crossroads in the deep bush, and with a bribe of a handful of sweets dished them out to black and white and brown urchins they met on the roadside, with instructions to take them to their homestead or kraal or camp and hand them to their elders.

X5000 REWARD L5ooo For information leading to the rescue Of CENTAINE DE THIRY COURTNEY A SURVIVOR OF THE HOSPITAL SHIP PROTEA CASTLE most barbarously torpedoed by a GERMAN SUBMARINE on the 28th Aug. 1917 off the coast Of SWAKOPMUND.

MRS COURTNEY would have been cast ashore and may be in the care of wild TRIBESMEN or alone in the WILDER NESS.

Any information concerning her whereabouts should be conveyed to the undersigned at the KAISERHOF HOTEL

WINDHOEK.

LT. COL. G. C. COURTNEY Five thousand pounds was a fortune, twenty yearssalary for the average working man, enough to buy a ranch and stock it with cattle and sheep, enough to provide a man with a secure living for his entire life, and there were dozens eager to try for the reward, or for any lesser amount that they could wheedle out of Garry by vague promises and fanciful stories and outright lies.

In the Kaiserhof suite he and Anna interviewed hopefuls who had never ventured beyond the line of rail but were willing to lead expeditions into the desert, others who knew exactly where the lost girl could be found, still others who had actually seen Centaine and only needed a grubstake of SI,Ooo to go and fetch her in. There were spiritualists and clairvoyants who were in constant con Sir tact with her, on a higher plane, and even one gentleman who offered to sell his own daughter, at a bargain rate, to replace the missing girl.

Garry met them all cheerfully. He listened to their V stories and chased their theories and instructions, or sat around an ouija board with the spiritualists, even followed one of them who was using one of Centaine's rings suspended on a piece of string as a lodestone, on a fivehundred-mile pilgrimage through the desert. He was presented with a number of young ladies, varying in texture and colour from blonde to caM all lait, all claiming to be Centaine de Thiry Courtney, or willing to do for him anything that she could do. Some of them became loudly abusive when they were refused and had to be evicted from the suite by Anna in person.

No wonder she is losing weight, Garry told himself, and leaned over to pat Anna's thigh as she sat beside him in the open Fiat tourer. The words of the blasphemous old grace came into his mind:We thank the Lord for what we have, But for a little more we would be glad. He grinned at her fondly, and aloud he told her, We should be there soon. She nodded and replied, This time I know we will find her. I have a sure feeling! Yes, Garry agreed dutifully. This time will be different. He was quite safe in that assertion. No other of their many expeditions had begun in such a mysterious manner.

One of their own reward posters had arrived folded upon itself and sealed with wax, bearing a postmark dated four days previously at Usakos, a way station on the narrow-gauge railway line halfway between Windhoek and the coast. The package was unstamped, Garry had been obliged to pay the postage, and it was addressed in a bold but educated band, the script unmistakably German.

When Garry split the wax seal and unfolded it he found a laconic invitation to a rendezvous written on the foot of the sheet, and a hand-drawn map to guide him. The sheet was unsigned.

Garry immediately telegraphed the postmaster at Usakos, confident that the volume of business at such a remote station would be so low that the postmaster would remember every package handed in for postage.

The postmaster did indeed recall the package and the circumstances of its delivery. It bad been left on the threshold of the post office during the night and nobody had

even glimpsed the correspondent.

As the writer probably intended, all this intrigued both Garry and Anna, and they were eager to keep the rendezvous. it was set for a site in the barren Kamas Hochtland a hundred and fifty miles from Windhoek.

It had taken them all of three days to negotiate the atrocious roads, but after losing themselves at least a dozen times, changing approximately the same number of punctured tyres, and sleeping rough on the hard ground beside the Fiat, they had now almost reached the appointed meeting place.

The sun blazed down from a cloudless sky and the breeze from behind blew eddies of red dust over them as they rattled and rumbled over the stony ruts. Anna seemed impervious to all the heat and dust and hardship of the desert and Garry, gazing at her in unstinted admiration, almost missed the next tight bend in the track. His off-wheels skidded over the verge, and the Fiat teetered and rocked over the yawning void that opened abruptly before them. He hauled the steering over, and as they bumped back into the wheel ruts he pulled on the handbrake.

They were on the rim of a deep canyon that cut the plateau like an axe stroke. The track descended into the depths in a series of hairpin twists like the contortions of a maimed serpent, and hundreds of feet below them the river was a narrow ribbon that threw dazzling reflections of the noon sun up the orange-coloured cliffs.

This is the place, Garry told her, and I don't like it.

Down there we will be at the mercy of any bandit or murderer. Mijnheer, we are already late for the meeting-'I don't know if we'll ever get out of there again, and ows, nobody is likely to find us here. Probably God kn just our bare bones. Come, Mijnheer, we can talk later. Garry drew a deep breath. Sometimes there were distinct drawbacks to being paired with a strong-willed woman. He let off the handbrake and the Fiat rolled over the rim of the canyon, and once they were committed, there was no turning back.

It was a nightmare descent, the gradient so steep that hairpin bends so tight the brake shoes smoked, and the that he had to back and fill to coax the Fiat through them. Now I know why our friend chose this place. He has us at his mercy down here. Forty minutes later they came out in the gut of the canyon. The walls above them were so sheer that they blotted out the sun. They were in shadow, but it was stiflingly hot. No breeze reached down here, and the air had a flinty bite on the back of the throat.

There was a narrow strip of level land on each bank of the river, covered with coarse thorn growth, and Garry nd they clim backed the Fiat off the track a bed down stiffly and beat the red dust from their clothing. The m bubbled sullenly over a low causeway of rock, and strea the water was opaque and a poisonous yellow colour like the effluent from a chemical factory.

J Y Well, Garry surveyed both banks and the cliffs above them, we seem to have the place to ourselves. Our friend is nowhere to be seen. We will wait. Anna forestalled the suggestion she knew was coming.

Of course, Mevrou. Garry lifted his hat and mopped his face with the cotton bandanna from around his neck. May I suggest a cup of tea? Anna took the kettle and went down the bank. She tasted the river water suspiciously, and then filled it.

When she climbed back, Garry had a fire of thomwood crackling between two hearthstones. While the kettle boiled, Garry fetched a blanket from the back of the Fiat, and the bottle of schnapps from the cubbyhole. He poured a liberal dram into each of the mugs, added a heaped spoon of sugar, then topped them up with strong hot tea.

He had found that schnapps, like chocolate, had a most tempering effect on Anna, and he was never without a bottle. Perhaps the journey would not be entirely wasted, he thought, as he added another judicious splash of spirits into Anna's mug and carried to to where she sat in the middle of the rug.

Before he reached her, Garry let out a startled cry and dropped the mug, splashing his boots with hot tea. He stood staring into the bush behind her, and raised both hands high above his head. Anna glanced round and then bounded to her feet and seized a brand of firewood which she brandished before her. Garry edged swiftly to her side and stood close to her protective bulk.

Keep away! Anna bellowed. I warn you, I'll break the first skull– They were surrounded. The gang had crept up on them through the dense scrub.

Oh Lord, I knew it was a trap! Garry muttered. They sis were almost certainly the most dangerous-looking band of cut-throats he had ever seen.

We have no money, nothing worth stealing– How many of them? he wondered desperately. Three, no, there was another behind that tree, four murderous ruffians. The obvious leader was a purple-black giant with bandoliers of ammunition crisscrossing his chest, and a Mauser rifle in the crook of his arm. A ruff of thick woolly beard framed his broad African features like the mane of a man-eating lion.

The others were all armed, a mixed band of Khoisan Hottentots and Ovambo tribesmen, wearing odd items of military uniform and civilian clothing, all of it heavily worn and faded, patched and tattered, some of them barefooted and others with scuffed boots, shapeless and battered from hard marches. Only their weapons were well cared for, glistening with oil and home lovingly, almost the way a father might carry his firstborn son.

Garry thought fleetingly of the service revolver he kept bolstered under the dashboard of the Fiat, and then swiftly abandoned such a reckless notion.

Don't harm us, he pleaded, crowding up behind Anna, and then with a feeling of utter disbelief, Garry found himself abandoned as Anna launched her attack.

Swinging the burning log like a Viking's axe, she charged straight at the huge black leader.

Back, you swine! she roared in Flemish. Get out of here, you bitch-born son of Hades! Taken by surprise, the gang scattered in pandemonium, trying to duck the smoking log as it hissed about their heads.

How dare you, you stinking bastard spawn of diseased whores-, Still shaking with shock, Garry stared after her, torn A between terror and admiration for this new revelation of cursers in his life, there had been the legendary sergeantmajor whom he had known during the Zulu rebellion; men travelled miles to listen to him addressing a parade ground. The man was a Sunday School preacher in comparison. Garry could have charged admission fees to Anna's performance. Her eloquence was matched only by her dexterity with the log.

She caught one of the Hottentots a crashing blow between the shoulders and he was hurled into a thorn bush, his jacket smoking with live coals, shrieking like a wounded wart hog. Two others, reluctant to face Anna's wrath, leaped over the river bank and disappeared with high splashes beneath the yellow waters. That left only the big black Ovambo to bear the full brunt of Anna's onslaught. He was quick and agile for such a big man, and he avoided the wild swings of the log and danced behind the nearest camel-thorn tree. With nimble footwork he kept the trunk between Anna and himself, until at last she stopped, gasping and redfaced, and panted at him, Come out, you yellow-bellied black-faced apology for a blue-testicled baboon! Garry noticed with awe how she managed to cram the metaphor with colour. Come out where I can kill you! Warily the Ovambo declined, backing off out of reach. No! No! We did not come to fight you, we came to fetch you– he answered in Afrikaans. She lowered the log slowly.

Did you write the letter? and the Ovambo shook his head. I have come to take you to the man who did. The Ovambo ordered two of his men to remain and guard the Fiat. Then he led them away along the floor of the canyon. Although there were stretches of open easygoing on the river bank, there were also narrow gorges through which the river roared and swirled, and the path was steep and so narrow that only one man could pass at a time.

These gaps were guarded by other guerillas. Garry saw only the tops of their heads and the glint of their rifle barrels amongst the rocks, and he noticed how cunningly the site for the rendezvous had been chosen. Nobody could follow them undetected. An army would not be able to rescue them. They were totally vulnerable, completely at the mercy of these rough hard men. Garry shivered in the sweltering gut of the canyon.

We'll be damned lucky to get out of this, he muttered to himself, and then aloud, My leg is hurting. Can't we rest? But no one even looked back at him, and he stumbled forward to keep as close to Anna as he was able.

Quite unexpectedly, long after Garry had relapsed into resigned misery, the Ovambo guide stepped around the corner of a yellow sandstone monolith and into a temporary camp site under an overhanging cliff on the river bank. Even in his exhaustion and unhappiness, Garry saw that there was a steep pathway up the canyon wall behind the camp, an escape route against surprise attack.

They have thought of everything. He touched Anna's arm and pointed out the path, but all her attention was on the man who sauntered out from the deep shadow of the cavern.

He was a young man, half Garry's age, but in the first seconds of their meeting he made Garry feel inadequate and foolish. He didn't have to say a word. He merely stood in the sunlight and stared at Garry with a catlike stillness about his tall elegant frame, and Garry was reminded of all the things he was not.