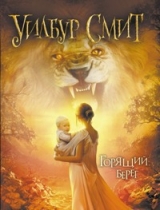

Текст книги "The Burning Shore"

Автор книги: Wilbur Smith

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

Without speaking again, without even being able to see more than each other's vague shapes in the darkness, they quickly learned to balance the raft between them with coordinated, subtle movements of their bodies. The wind increased in viciousness, but although the sea rose with it, they managed to keep the higher side of the raft headed into it, and only an occasional burst of spray splattered over them.

After a while, Centaine lapsed into an exhausted sleep, so deep that it was almost comatose. She awoke in daylight, a muted grey and dreary light in a world of wild grey waters and low sagging grey clouds. Her companion on the raft was squatting on the canted insecure deck beside her, and he was watching her steadfastly.

Miss Sunshine, he said, as soon as she stirred and opened her eyes. Never guessed it was you when you came aboard last night. She sat up quickly and the tiny raft dipped and rocked dangerously under them.

Steady on, luv, that's the ticket. He put out a gnarled hand to restrain her. There was a tattoo of a mermaid on his forearm.

My name's Ernie, miss. Leading Seaman Ernie Simpson. Of course, I knew you right away. Everybody on board knows Miss Sunshine."He was skinny and old, thin grey hair plastered with salt to his forehead, and his face wrinkled as a prune, but though his teeth were yellow and crooked, his smile was kindly.

What has happened to the others, Ernie? Frantically, Centaine looked around her, the true horror of their situation coming over her again. Gone to Davy Jones, most of them.

Davy Jones, who is he? Drowned, I mean. Rot the bloody Hun who did it. The night had hidden the true extremity of their situation from Centaine. The reality that was revealed now was infinitely more frightening than her imaginings. As they dropped into the swells, they were dwarfed by the cold opaque canyons of the sea, and as they rode up and over the crests, the vista of loneliness was such as to force Centaine to cringe down on the tiny deck. There was nothing but the water and the sky, no lifeboat nor swimmer, not even a seabird.

We are all alone, she whispered. Taus seuls. Cheer up, luv. We are still kicking, that's what counts. Ernie had been busy while she still slept. She saw that he had managed to glean a few fragments of debris and floating wreckage from the sea around them. There was a sheet of heavy-gauge canvas dragging behind the raft, around its edge short lengths of hemp rope had been spliced into eye holes. It floated like some monstrous octopus with limp tentacles.

Lifeboat cover, Ernie saw her interest. And those are ship's spars and some other odds and sods, begging your pardon, miss, never know what will come in useful. He had lashed this collection of wreckage together with the lengths of rope from the lifeboat cover, and even while he explained to Centaine, he was working with scarred but nimble fingers splicing short pieces of rope into a single length.

I'm thirsty, Centaine whispered. The salt had scalded her mouth and her lips felt hot and bloated.

Think about something else, Ernie advised. Here, give us a hand with this. Can you splice? Centaine shook her head. Ernie dropped all his aitches and as a French woman, she sympathized with him, and found it easy to like him.

It's easy, come on, luv. I'll learn you how. Watch!Ernie had a clasp knife attached by a lanyard to his belt, and he used the spike on the back of it to open the weave of the hemp. One over one, like a snake into its hole! See!Quickly Centaine got the hang of it. The work helped to take her mind off their awful predicament.

Do you know where we are, Ernie? I'm no navigator, Miss Sunshine, but we are west of the coast of Africa, how far off I haven't a clue, but somewhere out there is Africa. Yesterday at noonsight, we weremiles offshore."I'm sure you're right, Ernie nodded. All I know is we've got the current helping us, and the wind also– He turned his face up to the sky. if only we can use the wind. Have you got a plan, Ernie? Always got a plan, miss, not always a good one, I admit. He grinned at her. Just get this rope finished first. As soon as they had a single length of rope, twenty feet long, Ernie handed her the clasp knife.

Tie it around your middle, luv. That's the ticket. We don't want to drop it now, do we? He slid over the side of the raft and paddled like a dog to the dragging wreckage. With Centaine heaving and shoving under his direction, they worked two of the salvaged spars into position and lashed them securely with the hemp rope.

Outriggers, Ernie spluttered with seawater. A trick I learned from the darkies in Hawaii. The raft was dramatically stabilized, and Ernie crawled back on board. Now we can think about putting up some kind of sail. It took four abortive attempts before the two of them were able to rig a jury mast, and hoist a sail hacked from the canvas of the boat cover.

We aren't going to win the America's Cup, luv, but we are moving. Look at the wake, Miss Sunshine. They were spreading a sluggish oily wake behind their cumbersome craft, and Ernie trimmed their tiny sail carefully.

Two knots at least, he estimated. Well done, Miss Sunshine, you're a game one, and no mistake. Couldn't have done that alone. He was perched on the stern of the raft, steering with a salvaged length of timber as a tiller. Now you settle down and take a rest, luv, you and I will have to stand watches, back to back. All the rest of that day the wind came at them in gusts and squalls, and twice their clumsy mast was thrown overboard. Each time Ernie had to go into the water to retrieve it, and the effort required to lift the heavy spar and the wet canvas, then to restep and lash it back in place, left Centaine trembling and exhausted.

At nightfall the wind moderated and held steady and gentle out of the south-west. The clouds broke up so they had glimpses of the stars.

I'm tuckered out. You'll have to take a turn at the tiller, Miss Sunshine. Ernie showed her how to steer, and the raft responded sullenly to the push of the tiller. That red star there, that's Antares, with the small white star on each side of him, just like a sailor on shore leave with a girlfriend on each arm, begging your pardon, Miss Sunshine, but you just keep heading towards Antares and we'll be all right. The old seaman curled up at her feet like a friendly dog, and Centaine crouched on the stem of the raft and held the crude tiller under one arm. The swells dropped with the wind and it seemed to her that their passage through the water was faster. Looking back, she could see the green phosphorescence of their wake spreading out behind them. She watched the red giant Antares with his two consorts climb up the black velvet curtain of the sky.

Because she was lonely and still afraid, she thought of Anna.

My darling Anna, where are you? Are you still alive?

Did you reach one of the lifeboats, or are you, too, clinging to some scrap of wreckage, waiting on the judgment of the sea? Her longing for the solid bulky assurance of her old nurse was so intense that it threatened to turn her into a child once more, and she felt the childlike tears scalding her eyelids, and Antares glaring red light blurred and multiplied before her. She wanted to crawl into Anna's lap and bury her face in the warm, soapy smell of her vast bosom, and she felt all the resolve and purpose of the day's struggle melt in her, and she thought how easy it would be to lie down beside Ernie and not have to try any more.

She sobbed aloud.

The sound of her own sob startled her, and suddenly she was angry with herself and her own weakness. She wiped the tears away with her thumbs and felt the gritty crunch of dried salt crystals on her eyelashes. Her anger grew stronger, and deliberately she turned it away from herself to the fates which so afflicted her.

Why? she demanded of the great red star. What have I ever done that you single me out? Are you punishing me? Michel, and my father, Nuage and Anna, everything I have ever loved. Why do you do this to me? She broke off the thought, appalled at how close she had come to blasphemy. She hunched over, placed her free hand on her own belly and shivered with the cold. She tried to feel some sign of the life in her body, some swelling, some lump, some movement, but she was disappointed and her anger returned full strength, and with it a kind of wild defiance.

I make a vow. As mercilessly as I have been afflicted, so hard will I fight to survive. You, whether you are God or Devil, have thrust this upon me. So I give you my oath. I will endure, and my son will endure through me. She was raving.

She realized it but did not care, she had nsen to her knees and was shaking her fist at the red star in defiance and anger.

Come! she challenged. Do your worst, and let's have done! If she had expected a blast of thunder and a lightning bolt, there was none, only the sound of the wind in the rude mast and the scrap of sail, and the bubble of the wake under the stern of the raft. Centaine sagged back on to her haunches and gripped the tiller and grimly pointed the raft up into the east.

In the first light of the day, a bird came and hovered above Centaine's head. It was a small seabird, the dark blue-grey of a rifle barrel with soft white chalky marks over its beady black eyes, and its wings were beautifully shaped and delicate, and its cry was lonely and soft.

Wake up, Ernie, Centaine cried, and her swollen lips split at the effort. and a bubble of blood ran down her chin. The inside of her mouth was furry and dry as an old rabbit skin, and her thirst was a bright, burning thing.

Ernie struggled up and looked about him dazedly. He seemed to have shrunk and withered during the night, and his lips were flaky and white and encrusted with salt crystals.

Look, Ernie, a bird! Centaine mumbled through her bleeding lips.

A bird, Ernie echoed, staring up at it. Land close. The bird turned and darted away, low over the water, and was lost to sight, steel-grey against the dark grey sea.

A-A in the middle of the morning Centaine pointed ahead, her mouth and her lips so desiccated that she could not speak. There was a dark tangled object floating on the surface just ahead of the raft. It wallowed and waved its tentacles like a monster from the depths.

Sea kelp! Ernie whispered, and when they were close enough, he gaffed it with the tiller arm and drew the heavy mat of vegetation alongside the raft.

The stalk of the kelp was thick as a man's arm and five metres long, with a bushy head of leaves at the end. It had obviously been torn from the rocks by the storm.

Moaning softly with thirst, Ernie cut a length of the thick stalk. Under the rubbery skin there was a pulpy section of stem, and a hollow air chamber within. Ernie shaved the pulp with the clasp knife and thrust a handful of the shavings into Centaine's mouth. It was running with sap. The taste was strong and unpleasant, iodine and peppery, but Centaine let the liquid trickle down her throat and whispered with delight. They gorged themselves on the juice of the kelp and spat out the pith. Then they rested a while and felt the strength flowing back into their bodies.

Ernie took the tiller again and headed the raft down the path of the wind. The storm clouds had blown away, and the sun warmed them and dried their clothing. At first they held their faces up to its caress, but soon it became oppressive, and they tried to huddle away from it in the tiny patch of shade from the sail.

When the sun reached its zenith, they were exposed to the scourge of its full strength and it sucked the moisture from their bodies. They squeezed a little more of the kelp juice, but now the unplesant chemical taste nauseated Centaine and she realized that if she vomited, she would lose so much of her precious uids. They could drink the kelp juice only sparingly.

With her back against the jury mast, Centaine stared out at the horizon, the great ring of threatening water that surrounded them unbroken except in the east where a line of sombre cloud lay low on the sea. it took her almost an hour to realize that despite the wind, the cloud had not changed shape. If anything, it had firmed and grown a hairline taller along the horizon. She could make out tiny irregularities, tow peaks and valleys that did not alter shape as ordinary clouds would.

Ernie, she whispered, Erme, look at those clouds. The old man blinked his eyes and then rose slowly into a crouch. He started to make a soft moaning sound in his throat, and Centaine realized it was a sound of joy.

She rose beside him, and for the first time looked upon the continent of Africa.

Africa rose from the sea with tantalizing deliberation, and then almost shyly swathed herself in the velvet robes of night and retreated once more from their gaze.

The raft trundled on gently through the hours of darkness, and neither of them slept. Then the eastern sky began to soften and glow with the dawn, the stars paled out and there close before them rose the great purple dunes of the Narnibian Desert. How beautiful it is! Centaine breathed. It's a hard fierce land, miss, Ernie cautioned her. But so beautiful. The dunes were sculptured in mauve and violet, and when the first rays of the sun touched the crests, they burned red gold and bronze.

Beauty is as beauty does, mumbled Ernie. Give me the green fields of old blighty and bugger the rest, begging your pardon, Miss Sunshine.

The yellow-throated gannets came out in long formations from the land, flying high enough to be gilded by the sunlight, and the surf upon the beaches sighed and rumbled like the breathing of the sleeping continent. The wind that had stood steadily behind them for so long now felt the land and eddied and twisted. It caught their tiny sail aback, and the mast collapsed and fell overboard in a tangle of canvas and ropes.

They stared at each other in dismay. The land was so very close, it seemed that they might reach out and touch it, and yet they were forced to go through the whole weary business of restepping the mast. Neither of them had the energy for this new endeavour.

Ernie roused himself at last, wordlessly untied the lanyard of the clasp knife and handed it to Centaine. She fastened it around her own waist as the old man slid over the side of the raft once again and paddled to the peak of the stubby mast. On her knees, Centaine began to untangle the sheets and lines. The knots had all swollen with moisture and she had to use the spike of the clasp knife to break them open.

She coiled the ropes, and looked up as Ernie called, Are you ready, luv? Ready. She stood and balanced uncertainly on the tossing raft with the guide rope from the top of the mast in her hands taking up the slack, ready to assist Ernie to raise it back into position.

Then something moved beyond the old man's bobbing head, and she froze and lifted her hand to shade her eyes.

She puzzled over the strangely shaped object. It rode high on the green current, as high as a man's waist, and the early morning sun glinted upon it like metal. No, not metal, but like a lustrous dark velvet. It was shaped like the sail of a child's yacht, and with a nostalgic pang she remembered the little boys around the village pond on a Sunday afternoon, dressed in their sailor suits, sailing their boats.

What is it, luv? Ernie had seen her expectant pose and her puzzled expression.

I don't know, she pointed. Something strange, coming towards us, fast, very fasCErnie swivelled his head.

Where? I don't see– At that moment a swell lifted the raft high.

God help us! screamed Ernie, and flailed the water with his arms, tearing at it in an ungainly frenzy as he tried to reach the raft. What is it? Help me out! Ernie gulped, smothering in his own wild spray. It's a bloody great shark. The word paralysed Centaine.

She stared in stony horror at the beast, as another swell lifted it high, and the angle of the sunlight changed to pierce the surface and spotlight it.

The shark was a lovely slaty-blue colour, dappled by the rippling surface shadows, and it was immense, much longer than their tiny raft, wider across the back than one of the hogsheads of cognac from the estate at Mort Homme. The double-bladed tail slashed as it drove forward, irresistibly attracted by the wild struggles of the man in the water, and it surged down the face of the swell.

Centaine screamed and recoiled.

The shark's eyes were a catlike golden colour with black, spade-shaped pupils. She saw the nostril slits in its massive, pointed snout.

Help me! screamed Ernie. He had reached the edge of the raft and was trying to drag himself on board4 He was kicking up a froth of water and the raft rocked wildly and listed towards him.

Centaine dropped to her knees and grabbed his wrist.

She leaned back and pulled with all the strength of her terror, and Ernie slid halfway up on to the raft, but his legs still dangled over the side.

The shark seemed to hump out of the water, its back rose glistening blue, streaming with sea water, and the tall fin stood up like an executioner's blade. Centaine had read somewhere that a shark rolled on its back to attack, so she was unprepared for what happened now.

The great shark reared back and the grinning slit of its mouth seemed to bulge open. The lines of porcelain-white fangs, rank upon rank of them, came erect like the quills of a porcupine as the jaws projected outwards, and then they closed over Ernie's kicking legs. She clearly heard the grating rasp of the serrated edges of its fangs on bone, then the shark slid back, and Ernie was jerked backwards with it.

Centaine kept her grip on his wrist, although she was pulled down on to her knees and started to slide across the wet deck. The raft listed over steeply under their combined weight and the heavy drag of the shark on Ernie's legs.

Centaine could see its head under the surface for an instant. Its eye stared back at her with a fathomless savagery, and then the inner nictitating membrane slid across it in a sardonic wink, and quite slowly the shark rolled in the water with the irresistible weight of a teak log, exerting a shearing strain on to the jaws still clamped over Ernie's legs.

Centaine heard the bones part with a sound like breaking green sticks.

The drag on the old man's body was released so suddenly that the raft bobbed up and swung like a crazy pendulum in the opposite direction.

Centaine, still with her grip on Ernie's arm, fell backwards, dragging him up on to the raft after her. He was still kicking, but both his legs were grotesquely foreshortened, taken off a few inches below the knee, the stumps protruding from the torn cuffs of his duck trousers. The cuts were not clean, dangling ribbons of torn meat and skin flapped from the stumps as Ernie kicked, and the blood was a bright fountain in the sunlight.

He rolled over and sat up on the pitching raft, and stared at his stumps. Oh merciful mother, help me! he moaned. I'm a dead man. Blood spurted from the open arteries, dribbled and ran in rivulets across the white deck, cascaded to the surface of the sea and stained it cloudy brown. The blood looked like smoke in the water.

My legs! Ernie clutched at his wounds, and the blood fountained up between his fingers. My legs are gone. The devil has taken my legs. There was a huge swirl almost under the raft, and the dark triangular fin came up and knifed the surface, cutting through the discoloured water.

He smells the blood, Ernie cried. He won't give up, the devil. We are all dead men. The shark turned, rolling on his side, so they saw his snowy belly and the wide grinning jaws, and he came back, sliding through the bright clear water with majestic sweeps of his tail. He thrust his head into the blood clouds, and the wide jaws opened as he gulped at the taste. The scent and the taste infuriated him and he turned again; the waters roiled and churned at the massive movement below the surface, and this time he drove straight under the raft.

There was a crash as the shark struck the underside of the raft with his back, and Centaine was thrown flat with the force of the impact. She clung to the raft with clawed fingers. He is trying to capsize us, shouted Ernie. Centaine had never seen so much blood. She could not believe that the thin ancient body held so much, and still it spurted from Ernie's severed stumps.

The shark turned and came back. Again the heavy crash of rubbery flesh into the timbers of the raft and they were lifted up high. The raft hovered on the edge of capsizing and then fell back on to an even keel and bobbed like a cork.

He won't give up, Ernie was sobbing weakly. Here he comes again. The shark's great blue head rose out of the water, the jaws opened and then closed on the side of the raft. Long white fangs locked into the timber, and it crunched and splintered as the shark hung on.

It seemed to be staring directly at Centaine as she lay on her belly clinging to the struts of the raft with both hands. It looked like a monstrous blue hog, snuffling and rooting at the frail timbers of the little raft. Once again it blinked its eyes, the pale translucent membrane slipping over inscrutable black pupils was the most obscene and terrifying thing Centaine had ever seen, and then it began to shake its head, still gripping the side of the raft in its jaws. They were thrown about roughly, as the raft was lifted out of the water and swung from side to side.

Good Christ, he'll have us yet! Ernie dragged himself away from the grinning head. He'll never stop till he gets us! Centaine leapt to her feet, balancing like an acrobat, and she seized the thick wooden tiller and swung it high overhead. With all her strength she brought it down on the tip of the shark's hoglike snout. The blow jarred her arms to the shoulders, and she swung again and then again. The tiller landed with a rubbery thump, then bounced off the great head without even marking the sandpapery blue hide, and the shark seemed not to feel it.

He went on worrying the side of the raft, rocking it wildly, and Centaine lost her balance and fell half overboard, but instantly she dragged herself back and on her knees kept beating the huge invulnerable head, sobbing with the effort of each stroke. A section of the woodwork tore away in the shark's jaw's, and the blue head slipped below the surface again, giving Centaine a moment's respite.

He's coming back! Ernie cried weakly. He will keep coming back, he won't give up! And as he said it, Centaine knew what she had to do. She couldn't allow herself to think about it. She had to do it for the baby's sake. That was all that counted, Michel's son.

Ernie was sitting flat on the edge of the raft, those fearfully mutilated limbs thrust out in front of him, turned half away from Centaine, leaning forward to peer down into the green waters below the raft.

Here he comes again! he shrieked. His sparse grey hairs were slicked down over his pate by seawater and diluted blood. His scalp gleamed palely through this thin covering. Beneath them the waters roiled, as the shark turned to attack once more, and Centaine saw the dark bulk of him coming up from the depths, driving back at the raft.

Centaine came to her feet again, Her expression was stricken, her eyes filled with horror, and she tightened her grip on the heavy wooden tiller. The shark crashed into the bottom of the raft, and Centaine reeled, almost fell, then caught her balance.

He said himself he was a dead man. She steeled herself.

She lifted the tiller high and fixed her gaze on the naked pink patch at the back of Ernie's head and then with all her strength she swung the tiller down in an axe-stroke.

She saw Ernie's skull collapse under the blow.

Forgive me, Ernie, she sobbed, as the old man fell forward and rolled to the edge of the raft. You were dead already, and there was no of er way to save my baby. The back of his skull was crushed in, but he rolled his head and looked at her. His eyes were afire with some turbulent emotion and he tried to speak. His mouth opened, then the fire in his eyes died and his limbs stretched and relaxed.

Centaine was weeping as she knelt beside him.

God forgive me, she whispered, but my baby must live. The shark turned and came back, its dorsal fin standing higher than the deck of the raft, and gently, almost tenderly, Centaine rolled Ernie's body over the side.

The shark whirled. It picked up the body in its jaws and began to worry it like a mastiff with a bone, and as it did so the raft drifted away. The shark and its victim sank gradually out of sight into the green waters and Centaine found she still had the tiller in her hands.

She began to paddle with it, pushing the raft towards the beach. She sobbed with each stroke, and her vision was blurred. Through her tears she saw the kelp beds swaying and dancing at the edge of the ocean, and beyond them the surf humping and then hissing over a beach of brassy yellow sands. She paddled in a dedicated frenzy, and an eddy of the current caught the raft, assisting her efforts, and bore it in towards the beach. Now she could see the bottom, the corrugated patterns of sea-washed sands, through the limpid green water.

Thank you, God, oh thank you, thank you! she sobbed in time to her strokes, and then again there came that shattering impact of a huge body into the underside of the raft.

Centaine clung desperately to the strut again, her spirits plunging with despair. It's come back again.

She saw the massive dappled shape pass beneath the raft, starkly outlined against the gleaming sandy bottom.

It never gives up. She had won only temporary respite.

The shark had devoured the sacrifice she had offered it within minutes, then drawn by the odour of the blood that was still splattered over the raft, it had followed her into water barely as deep as a man's shoulder.

It came around in a wide circle and then raced in from the sea side to attack the raft again, and this time the impact was so shattering that the raft began to break up.

The planks bad been worked loose by the heavy flogging of the storm, and they opened now under Centaine, so her legs dropped through and she touched the horrid beast beneath the raft. She felt the rasping of its coarse hide across the soft skin of her calf, and screamed as she jackknifed her lower body up away from it.

Inexorably the shark circled and came back, but the slope of the beach forced it to come from the sea side and its next attack, murderous as it was, drove the raft in closer to the beach, and for a moment or two the colossal beast was stranded on the shelving sand. Then, with a swirl and a high splash, it pulled free and circled out into deeper water, but with its fin and broad blue back exposed-.

A wave hit the raft, completing the demolition that the shark had begun, and the raft shattered into a welter of planks and canvas and dangling ropes. Centaine was tumbled into the surging waters, and spluttering and coughing came to her feet.

She was breast-deep in the cold green surf, and through eyes streaming with salt water, she saw the shark come boring full at her. She screamed and tried to back up the shelving beach, brandishing the tiller she still had in her hands. Get away! she screamed. Get away! Leave me!

The shark hit her with his snout and threw her high in the air. She fell back on top of the huge black back, and it reared under her like a wild horse. The feel of it was cold and rough and unspeakably loathsome. She was thrown clear of it and then was struck a heavy blow by the flailing tail. She knew it had been a glancing blow a full sweep of that tail would have crushed in her ribcage.

The shark's own wild thrashing had churned up the sandy bottom, blinding it so that it could not see its prey, but it sought her with its mouth in the turbid water. The jaws champed like an iron gate slamming in a hurricane, and Centaine was beaten and hammered by the swinging tail and the massive contortions of the blue body.

Slowly she fought her way up the sloping beach. Every time she was knocked down, she struggled up, gasping and blinded and striking out with the tiller. The gnashing fangs closed on the thick folds of her skirt and ripped them away, and immediately her legs were freed. As she stumbled back a last few paces, the level of the water fell below her waist.

At the same moment, the surf drew back, sucking away from the beach, and the shark was stranded, suddenly powerless as it was deprived of its natural element. It wriggled and writhed on the sand, helpless as a bull elephant in a pitfall, and Centaine backed away from it, knee-deep in the dragging surf, too exhausted to turn and run, until miraculously she realized that she was standing on hard-packed sand above the waterline.

She threw the tiller aside and staggered up the beach towards the high dunes. She did not have the strength to go that far. She collapsed just above the high-water line and lay face down in the sand. The sand coated her face and body like sugar, and she lay in the sunlight and wept with the fierce gales of fear and sorrow and remorse and relief that racked her entire body.

She had no idea how long she lay in the sand, but after a while she became aware of the sting of the harsh sunlight on the backs of her bare legs, and she sat up slowly.

Fearfully she looked back to the edge of the surf, expecting still to see the great blue beast stranded there, but the flooding tide must have lifted it and it had escaped out into deep water. There was no sign of it at all. She let out her breath in an involuntary gasp of relief and stood up uncertainly.

Her body felt battered and crushed and very weak, and looking down at it she saw how contact with the rough abrasive hide of the shark had grazed her skin raw, and that already there were dark blue bruises spreading across her thighs. Her skirts had been torn off her by the shark, and she had discarded her shoes before she jumped from the deck of the hospital ship, so except for her sodden uniform blouse and a pair of silk carni-knickers, she was naked. She felt a rush of shame, and looked around her quickly. She had never been further from other human presence in her life.