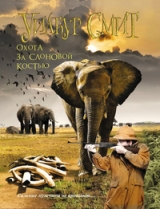

Текст книги "Elephant Song"

Автор книги: Wilbur Smith

Соавторы: Wilbur Smith

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Once again the camera crew climbed the steel ladder up to the central platform of the MOMU. Chetti Singh and Ning Cheng Gong had disappeared, and that made Daniel even more uneasy. From the height of the platform they could look down on to the tube mills. These were four massive steel drums, lying horizontally on the deck of the MOMU, and revolving like the spin-dryer in a domestic washing-machine. However, these drums were forty yards long, and each one was loaded with one hundred tons of cast-iron cannonballs. The red earth coming up from the excavated trench on the conveyor belts was

continually being dumped into the open mouths of the drums.

As the earth passed down the length of the drum, the clods and rocks were pounded to fine talcum by the tumbling iron balls.

The red powder that poured from the far end of the tube mills went directly into the separator tanks.

The film team moved down the steel catwalks until they were above the separators, and here Taffari continued his explanation for the benefit of Bonny's camera. The two valuable minerals that we are after are either very heavy or magnetic. The rare earth monazite is collected by powerful electromagnets. His voice was almost drowned by the roar of the machinery. That didn't worry Daniel. Later he would have Taffari make another clear recording of his speech and in the studio be would dub the tape to give it good sound. Once we have taken out the monazite, the remainder goes into the separator tanks in which we float out the light material and capture the heavy ore of platinum. Taffari went on, This is a very sensitive part of the operation. If we were to use chemical catalysts and reagents in the separator tanks we would be able to recover over ninety percent of the platinum. However, the chemical effluent from the tanks would be poisonous.

It would be absorbed into the earth and washed by rain into the rivers to kill everything that came in contact with it animals, birds, insects, fish and plant life. As president of the Democratic People's Republic of Ubomo, I have given an inviolable instruction that no chemical reagents of any kind are to be used during platinum mining operations in this country. Taffari paused and stared into the camera levelly. You have my absolute assurance on that point. Without using reagents, our recovery of ore drops to sixty-five percent. That means tens of millions of dollars are lost from the process. However, my government and I are determined to accept that loss, rather than to run any risk of chemical pollution of our environment.

We are determined to do all in our power to make this a safe and happy world for our children, and your children, to enjoy. He was utterly convincing. When you listened to that deep reassuring voice and looked at that noble face, you could not possibly doubt his sincerity. Even Daniel was moved, and his critical faculties were suspended for the moment. This bastard could sell pork pies in a synagogue. He tried to get his cynical professional judgement functioning again. Cut, he snapped. That's a wrap. That was marvelous, Mr. President. Thank you very much. If you'd like to go back to the mess for lunch, we'll finish up here. Then this afternoon we'll film the final sequences with the maps and models. Chetti Singh reappeared, like a turbaned genie from a lamp, to usher Taffari down from the MOMU and to drive him back to the base camp where Daniel knew a sumptuous buffet lunch was awaiting him.

The food and liquor had been flown up from Kahali in the Puma helicopter.

Once the others had left, Daniel and Bonny captured the last sequences on the MOMU which didn't require Taffari to be present. They filmed the heavy platinum concentrates pouring into the ore bins in a fine dark stream. Each bin had a capacity of a hundred tons and when it was full it dropped automatically on to the bed of a waiting trailer and was towed away.

It was three o'clock before they had wrapped up all the shots that Daniel wanted on the MOMU and by the time they got back to the base camp at Sengi-Sengi, the presidential lunch was just ending.

In the centre of the conference room of the headquarters hut was an elaborate scale model of a typical mining scenario, employing the MOMU unit. It was designed to illustrate the entire procedure. The model had been built by BOSS technicians in London. It was an impressive piece of work, complete in detail, authentic in scale.

Daniel planned to alternate between shots of the model and helicopter shots from the Puma of the actual forest terrain with the real MOMU in action. He believed that on the screen it would be difficult to tell the difference between them.

The scale model showed the mining track, sixty yards wide, cut and cleared through the forest by the team of loggers and bulldozers working ahead of the MOMU. Daniel planned to devote a few days filming to the logging operation itself. The felling of the tall trees would yield riveting footage. The ponderous arabesques of the yellow bulldozers dragging the logs out of the jungle, the gangs loading them on to the logging trucks, would all be good cinema.

In the meantime Daniel must take full advantage of the day's filming in which Taffari had agreed to participate. He watched Bonny fussing over him, whispering and giggling as she powdered his face. She was making it very obvious to anyone watching that they were lovers.

Taffari had drunk enough to lower his inhibitions and he caressed her openly, staring at the big breasts that she thrust only inches from his nose.

She really sees herself as First Lady of Ubomo, Daniel marveled.

She hasn't the least idea how the Hita treat their wives.

I'd love it to happen. She deserves anything that comes her way.

He stood up and interrupted the flagrant display. If you're ready, Mr.

President, I'd like you standing here, beside the table. Bonny, I want the shot from this side. Try to get both General Taffari and the model in focus.

Taffari moved to his mark and they rehearsed the shot. He got it right at the first attempt. Very good, sir. We'll go for it now. Are you ready, Bonny? Taffari's military swagger-stick was of polished ivory and rhino horn, the shaft topped by a miniature carving of an elephant. It looked more like a field marshal's baton than that of a general officer.

Perhaps he was anticipating the day when he would promote himself, Daniel thought wryly.

Now Taffari used the baton to point out the features of the model on the table in front of him. As you can see, the mining track is a narrow pathway through the forest, only sixty yards wide. It is true that along that track we are felling all the trees and removing the undergrowth for the MOMU to follow. He paused seriously, and looked up at the camera. This is not wanton destruction but a prudent harvest, like that of a farmer husbanding his fields. Less than one percent of the forest is affected by this narrow strip of activity, and behind the MOMU comes a span of bulldozers to refill the mining trench and to compact and consolidate the soil. The trench itself is painstakingly following the land contours to avoid soil erosion.

As soon as the trench is refilled, a team of botanists follows up to replant the open ground with seeds and saplings. These plants have been carefully selected. Some of them are quickgrowing to act as a ground cover; others are slower growing, but in fifty years from now will be fully mature and ready to be harvested. I will not be there when this happens, but my grandchildren will. The way that this operation has been planned, we will never harvest more than one single percent of the forest each year. You don't have to be a mathematician to realise that it will be the year AD 2090 before we have worked it all, and by that time the trees that we plant now, in 1990, will be a hundred years old and we can safely begin the whole cycle over again.

He smiled reassuringly into the lens, handsome and debonair. A thousand years from now the forests of Ubomo will still be yielding up their largesse to generations yet unborn, and offering a haven for the same living creatures that they do now. It all made sense, Daniel decided. He had seen the proof of it in operation. That narrow track through the forest could not seriously threaten any species with extinction. Taffari was proposing exactly the same philosophy in which Daniel himself believed so implicitly, the philosophy of sustained yield, the disciplined and planned utilisation of the earth's resources, so that they were always renewing themselves.

For the moment, his animosity towards Ephrem Taffari was forgotten.

He felt like applauding him.

Instead he cleared his throat and said, Mr. President, that was an extraordinary performance. It was inspirational. Thank you, sir.

Sitting on the tailboard of the Landrover, Chetti Singh smoothed the document over his own thigh. He had developed a remarkable dexterity with his left hand.

This scrap of paper takes all the fun out of it, he remarked. It is not meant to be fun, Ning Cheng Gong said flatly. It is meant to be a present for my honourable father. It is meant to be work. Chetti Singh glanced up at him and smiled blandly and insincerely. He did not like the change that was so apparent since Ning had returned from Taipei.

There was a new force and strength in him now, a new confidence and determination.

For the first time Chetti Singh found that he was afraid of him.

He did not enjoy the sensation. Still, work goes better when it is fun, Chetti Singh argued to bolster himself, but found he could not meet Ning's dark implacable stare. He dropped his eyes to the document and read, PEOPLE's DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF Ubomo Special Presidential Game Licence The bearer, Mr. Ning Cheng Gong, or his authorised agent, is hereby empowered by special presidential decree to hunt, trap or kill the following protected species of wild game anywhere in the Republic of Ubomo. To wit, five specimens of Elephant (Loxodonta Africana).

He is further empowered for reasons of scientific research to collect and have in his possession, to export or sell, any part of the aforesaid specimens including the skins, bones, meat and, or ivory tusks thereof.

Signed, Ephrem Taffari President of the Republic.

The licence was a rush job. There was no precedent for the form or wording of it and at Cheng's request the president had scribbled it out on a scrap of notepaper and the government printer had set it up under the coat of arms of the Republic of Ubomo, and delivered it within twelve hours for President Taffari to sign.

I am a poacher, Chetti Singh explained, the best in Africa.

This piece of paper turns me into a mere agent, an underling, a butcher's apprentice. . .

Cheng turned away impatiently. The Sikh was annoying him.

There were things other than this petty carping to occupy him.

He paced the forest clearing, lost in thought. The ground was muddy and rutted underfoot and the humidity steamed up the lenses of his sunglasses. He removed them and slipped them into the breast-pocket of his open-neck shirt. He glanced around him at the solid green wall of jungle that hemmed in the clearing. It was dark and menacing and he suppressed the sense of unease that it evoked and instead glanced at his wristwatch. He is late, he said sharply. When will he come?

Chetti Singh shrugged and folded the game licence with one hand. He does not have the same sense of time that we do. He is a pygmy. He will come when it suits him. Perhaps he is already here, watching us.

Perhaps he will come tomorrow or next week. I cannot waste any more time, Cheng snapped. There is other important work to do. More important than your honourable father's gift? Chetti Singh asked, and his smile was ironical. Damn these black people.

Cheng turned away again. They are so unreliable. They are monkeys, Chetti Singh agreed, but useful little monkeys. Cheng made another turn around the clearing, his feet squelching in the red mud, and then stopped in front of Chetti Singh again. What about Armstrong? he asked.

We have to deal with him. Ah, yes! Chetti Singh grinned. That will be fun, indeed. He massaged the stump of his missing arm. I have dreamed about Doctor Armstrong every night for nearly a year. And yet I never thought to have him delivered so neatly to Sengi-Sengi.

Like a trussed chicken, never mind. You will have to deal with him while he is still here, Cheng insisted. You can't allow him to leave here alive. Perish the thought, Chetti Singh agreed. I have been devoting much contemplation to the problem. I wish the good doctor's demise to be suitably symbolic and painful, and yet to be adequately explainable as a most unfortunate accident of fate. Don't wait too long, Cheng warned!

I have five more days, Chetti Singh pointed out complacently. I have seen the filming schedule. He cannot finish his work at Sengi-Sengi before that-Cheng cut in impatiently, What about the red-haired woman, his assistant? At the moment President Taffari is having some honking fun with her, but nevertheless I think it might be prudent to arrange for her to accompany Doctor Armstrong on the long journey– Chetti Singh broke off abruptly and stood up. He peered into the forest and when Cheng opened his mouth to speak he silenced him with an imperative gesture. For another minute he stood listening with his head cocked before he spoke again. I think he is here. How do you know?

Despite himself Cheng's voice was a cautious whisper and he cleared his throat nervously as he peered into the jungle. Listen, said Chetti Singh. The birds. I hear nothing. Precisely. Chetti Singh nodded.

They have fallen silent.

He stepped towards the green wall and raised his voice, calling in Swahili. Peace be with you, son of the forest. Come forward, so that we may greet each other as friends. The pygmy appeared like a trick of the light in a hole in the wall of vegetation. He was framed in a wreath of shining green leaves, and a ray of sunshine through the top branches that surrounded the clearing danced upon his glossy skin and threw each muscle of his powerful little body into high relief. His head was small and neat. His nose was broad and flat and he wore a goatee beard of soft curling black wool, laced with silvery grey. I see you, Pirri, the great hunter, Chetti Singh greeted him with flattery and the little man came into the clearing with a lithe and graceful step. Did you bring tobacco?

he asked in Swahili, with a childlike directness, and Chetti Singh chuckled and handed him a-tin of Uphill Rhodesian.

Pirri unscrewed the lid. He scooped out a loose ball of yellow tobacco and wadded it under his top lip and hummed with pleasure. He is not as small as I thought he would be, Cheng remarked as he studied him. Or as dark. He is not a full-blooded Bambuti, Chetti Singh explained. His father was a Hita, or so it is said. Can he hunt?

Cheng asked dubiously. Can he kill an elephant? Chetti Singh laughed.

He is the greatest hunter of all his tribe, but that is not all. He has other virtues, not possessed by his brethren, by reason of his mixed blood.

What are they? Cheng wanted to know.

He understands the value of money, Chetti Singh explained. Wealth and property mean nothing to the other Bambuti, but Pirri is different. He is civilised enough to know the meaning of greed. Pirri was listening to them. Not understanding the English words, his head turned to each of them as they spoke, and he sucked his wad of tobacco.

He was dressed only in a brief loincloth of bark cloth, his bow standing up behind his shoulder and his machete in a wooden scabbard at his waist. Abruptly he interrupted their discussion of him. Who is this wazungu? he asked in Swahili, indicating Cheng with his woolly bearded chin. He is a famous chief, and rich, Chetti Singh assured him, and Pirri strode across the clearing on muscular legs with bulging calves and looked up at Cheng curiously. His skin has the malaria colour and his eyes are the eyes of the mamba, he announced without guile. Cheng understood just enough Swahili to bristle. He may know greed, but he does not know respect. It is the Bambuti way, Chetti Singh tried to placate him. They are like children; they say whatever comes into their heads. Ask him about the elephant, Cheng instructed, and Chetti Singh changed his tone of voice and smiled ingratiatingly at Pirri. I have come to ask you about elephant, he said, and Pirri scratched his crotch, taking a large handful of the contents of his loin-cloth and joggling it thoughtfully.

Ah, elephant he said vaguely. What do I know about elephant? You are the greatest hunter of all the Bambuti, Chetti Singh pointed out.

Nothing moves in the forest but Pirri knows of it. That is true, Pirri agreed, and studied Cheng reflectively. I like the bracelet on this rich wazungu's wrist, he said. Before we talk of elephant he should give me a gift. He wants your watch, Chetti Singh told Cheng.

I understood! Cheng snapped. He is impertinent. What would a savage do with a gold Rolex? He would probably sell it to one of the truck-drivers for one hundredth of its value, Chetti Singh replied, enjoying Cheng's anger and frustration. Tell him I will not be blackmailed. I will not give him my watch, Cheng stated flatly, and Chetti Singh shrugged. I will tell him, he agreed, but that will mean no gift for your honourable father. Cheng hesitated and then unclipped the gold bracelet from his wrist and handed it to the pygmy. Pirri cooed with pleasure and held the wristwatch in both hands, turning it so that the small diamonds around the dial sparkled. It is pretty, he giggled.

So pretty that suddenly I remember about the elephant in the forest.

Tell me about the elephant, Chetti Singh invited. There were thirty elephant cows and calves in the forest near Gondola, Pirri said. And two large bulls with long white teeth. How long? Chetti Singh demanded, and Cheng who had followed the conversation thus far leaned forward eagerly.

One elephant is larger than the other. His teeth are this long, said Pirri, and unslung his bow from his shoulder and held it above his head and stood on tiptoe. This long, he repeated. As high as I can reach with my bow, from the tip of the tooth to the lip, but not counting the part concealed in the skull. How thick? Cheng asked in atrocious Swahili, his voice coarse with lust, and Pirri turned to him and halfcircled his own waist with his dainty childlike hands. This thick, he said. As thick as I am. That is a great elephant, Chetti Singh murmured with disbelief, and Pirri bridled. He is the greatest of all elephants and I have seen him with my own eyes. I, Pirri, say this thing and it is true. I want you to kill this elephant and bring me his tusks, Chetti Singh said softly, and Pirri shook his head. This elephant is no longer at Gondola. When the machines of yellow iron came into the forest, he ran from their smoke and noise. He has gone into the sacred heartland where no man may hunt. It is decreed by the Mother and the Father. I cannot kill this elephant in the heartland.

I will pay you a great deal for the teeth of this elephant, Chetti Singh whispered seductively, but Pirri shook his head firmly. Offer him a thousand dollars, Cheng said in English, but Chetti Singh frowned at him.

Leave this to me, he cautioned. We don't want to ruin the trade with impatience. He turned back to Pirri and said in Swahili, I will give you ten bolts of pretty cloth which the women love, and fifty handfuls of glass beads, enough to make a thousand virgins spread their thighs for you. Pirri shook his head. It is the sacred heartland, he said.

The Mother and the Father will be angry if I hunt there. in addition to the cloth and beads, I will give you twenty iron axe-heads and ten fine knives with blades as long as your hand. Pirri wriggled his whole body like a puppy. It is against law and custom. My tribe will hate me and drive me out. I will give you twenty bottles of gin, Chetti Singh said.

And as much tobacco as you can lift from the ground. Pirri massaged his crotch frantically and rolled his eyes. As much tobacco as I can carry!

His voice was hoarse. I cannot do it. They will call out the Molimo.

They will bring down the curse of the Mother and Father. And I will give you a hundred silver Maria Theresa dollars. Chetti Singh reached into the pocket of his bush jacket and brought out a handful of silver coins. He juggled them in one hand, jingling them together and making them sparkle in the sunlight.

For a long moment Pirri stared at them hungrily. Then he let out a shrill yelp and sprang in the air and drew his machete.

Chetti Singh and Cheng stepped back nervously, expecting him to attack them, but instead, Pirri whirled and, with the blade held high above his head, rushed at the wall of the forest and swung a hissing stroke at the first bush. Shouting with anger and temptation, he hacked and slashed at the forest growth.

Leaves and twigs flew, and branches were sliced through. Slabs of bark and white wood rained down from the bleeding trunks under his onslaught.

At last Pirri stopped and rested on his blade, his muscular chest heaving, sweat pouring down his face and dripping into his beard, sobbing with exertion and self-loathing. Then he straightened up and came back to where Chetti Singh stood and said, I will kill this elephant for you, and bring you his teeth. then you will give me all those things you promised me, not forgetting the tobacco. Chetti Singh drove the Landrover back along the rudimentary forest track. it took almost an hour for them to reach the main corduroy roadway on which the convict gangs were working, and over which the great ore-carriers and the logging trucks rumbled and roared.

As they left the overgrown logging track and joined the heavy flow of traffic towards Sengi-Sengi, Chetti Singh turned to grin at the man beside him. That takes care of the gift for your father. Now we must apply all our ingenuity and brains to a little gift for me, the head of Doctor Daniel Armstrong on a silver platter, with an apple in his mouth.

Daniel had been waiting for this moment, praying for it.

He was high on the command deck of the MOMU and it was raining. The air was blue and thick with falling rain, and visibility was down to fifty feet or less. Bonny was sheltering in the command cabin at the end of the platform, keeping her precious video equipment out of the rain. The two Hita guards had gone down to the lower deck and for a moment Daniel was alone on the upper deck.

Daniel had become hardened to the rain. Since arriving at Sengi-Sengi he seemed always to be wearing wet clothing. He was standing now in the angle of the steel wall of the command cabin and the flying bridge, only partially shielded from the driving rain.

Every now and then a harder gust would throw heavy drops into his face and force him to slit his eyes.

Suddenly the door to the command cabin opened and Ning Cheng Gong came out on to the flying bridge. He had not seen Daniel and he crossed to the forward rail under cover of the canvas sun awning and leaned on the rail, peering down at the great shining excavator blades that were tearing into the earth seventy feet below his perch.

It was Daniel's moment. For the first time they were alone and Cheng was vulnerable. This one is for Johnny, he whispered, and crossed the steel plates of the bridge on silent rubber soles. He came up behind Cheng.

All he had to do was stoop and seize his ankles. A quick lift and shove, and Cheng would be hurled over the rail and dropped into the deadly blades. It would be instantaneous and the chopped and dismembered corpse would be fed into the tube mills and pounded to paste and mixed with hundreds of tons of powdered earth.

Daniel reached out to do it, but before he could touch him he hesitated involuntarily, suddenly appalled at what he was about to do.

It was cold-blooded, calculated murder. He had killed before as a soldier, but never like this, and for a moment he was sick with self-loathing. For Johnny, he tried to convince himself, but it Was too late. Cheng whirled to face him.

He was quick as a mongoose confronted by a cobra. His hands came up, the stiff-fingered blades of the martial arts expert, and his eyes were dark and ferocious as he stared into Daniel's face.

For a moment they were poised on the edge of violence, then Cheng whispered, You missed your chance, Doctor. There will not be another.

Daniel backed away. He had let Johnny down with such weakness. In the old days it would not have happened. He would have taken Cheng out swiftly and competently and rejoiced at the kill. Now the Taiwanese was alerted and even more dangerous.

Daniel turned away, sickened by his failure, and then he started.

One of the Hita guards had come up the steel ladder silently as a leopard. He was leaning against the rear rail of the bridge with his maroon beret cocked over one eye and the Uzi submachine-gun on his hip pointed at Daniel's belly. He had been watching it all.

That night Daniel lay awake until after midnight, unnerved by the narrowness of his escape and sickened by the savage streak in himself that allowed him to pursue such a brutal vengeance. Yet even this attack of conscience did not shake his determination to act as the vehicle of justice and in the morning he awoke to find his lust for revenge undiminished, and only his temper and his nerves shaky and uncertain.

This led directly to his final bust-up with Bonny Mahon. It began when she was late to start the day's assignment, and kept him waiting in the teeming rain for almost forty minutes before she finally sauntered out to meet him. When I said five o'clock, I didn't mean in the afternoon, he snarled at her, and she grinned at him, all rosy and smug. What do you want me to do, commit hara-kiri, Master? she asked. He was about to let fly a verbal broadside, when he realised that she must have come directly from Taffari's bed without bathing, for he caught a whiff of the musky odour of their lovemaking on her, and had to turn away. He felt so furious that he could not trust himself not to strike her.

For Chrissake, Armstrong, get a hold on yourself, he cautioned himself silently, you're going to pieces.

They worked in brittle antagonism for the rest of the morning, filming the bulldozers and chainsaws as they cleared the mining track for the monstrous MOMU to waddle down.

It was heavy going in the mud and rain, and dangerous with falling tree trunks and powerful machinery working all around them. This did nothing to improve his mood but Daniel managed to keep a check on his tongue until just before noon when Bonny announced that she had run out of tape and had to break off to return to the main camp to fetch new stock from the cold rooms. What kind of half-baked cameraman runs out of stock in the middle of a shoot? Daniel wanted to know, and she rounded on him. I know what's eating you up, lover boy. It's not shortage of film, it's shortage of good rich fruitcake. You hate me for what Ephrem is getting and you're not. It's the old green-eyed monster.

You've got an inflated idea of the value of what you sit on, Daniel came back as angrily.

It escalated rapidly from there until Bonny yelled into his face, Nobody talks to me like that, Buster. You can stick your job and your insults up your left earhole, or in any other convenient orifice. And she sloshed and slipped in the red mud back to where the Landrover was parked. Leave the camera in the Landrover, Daniel shouted after her.

it was all hired video equipment. You've got your return ticket to London and I'll send you a cheque for what I owe you.

You're fired. No, I'm not, lover boy. You're way too late. I resigned! And don't you forget it. She slammed the door of the Landrover and raced the engine. All four wheels spinning wildly and throwing up sheets and clods of red mud, Bonny tore up the track and left him glaring after her. His had temper increased as he belatedly thought of a dozen other clever retorts that he should have thrown at her while he had the chance.

Bonny was as angry, but her mood was longer-lasting and more vindictive.

She racked her imagination for the cruellest revenge she could conjure up, and just before she reached the main camp at Sengi-Sengi it came to her in a creative flash. You are going to regret every single lousy thing you said to me, Danny boy, she promised aloud, grinning mercilessly. You aren't going to shoot another tape in Ubomo, not you, nor any other cameraman that you hire to replace me. I'm going to make damned double sure of that. His body was long and supple. In the dim light beneath the mosquito-net his skin shone like washed coal, still damp with the sweat of love.

Ephrem Taffari lay on his back on the rumpled White sheet and she thought he was probably the most beautiful man she had ever seen.

Slowly she lowered her head and laid her cheek against his naked chest.

it was smooth and hairless, and his dark skin felt cool. She blew softly on his nipple and watched it pucker and harden in response. She smiled.

She felt aglow with well-being.

He was a wonderful lover, better than any white man she had ever had.

There had never been anyone else like him. She wanted to do something for him. There is something I must tell you, she whispered against his chest, and with one lazy hand he stroked the thick glistening coppery bush of hair back off her face. What is it? he asked, is voice so and deep and replete, almost uninterested.

She knew she would have his complete attention again with her next statement, and she delayed the moment. It was too sweet to waste. She wanted to draw every last possible enjoyment from it. it was double pleasure, her revenge on Daniel Armstrong and her offering to Ephrem Taffari which would prove to him her loyalty and her worth. What is it?