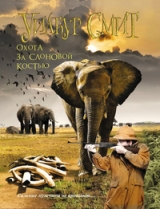

Текст книги "Elephant Song"

Автор книги: Wilbur Smith

Соавторы: Wilbur Smith

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

They would not follow the choked rivers upstream for fear of what they might find.

How many rivers are like this? Kelly demanded.

Many, many, Sepoo muttered, meaning moretban four. Name them for me, she insisted, and he reeled off the names of all the rivers she had ever visited in the region and some that she had only heard of. It seemed then that almost the entire drainage area of the Ubomo was affected.

This was notsome isolated local disturbance, but a large-scale disaster that threatened not only the Bambuti hunting areas but the sacred heartland of the forest as well. We must travel upstream, Kelly said with finality, and Sepoo, looked as though he might burst into tears.

They are waiting for you at Gondola, he squeaked, but Kelly did not make the mistake of beginning an argument. She had learned from the women of the tribe, from old Pamba in particular. She lifted her pack on to her back, adjusted the headband and started up the bank. For two hundred yards she was alone, and her spirits started to sink. The forest area ahead was completely unknown to her, and it would be folly to continue on her own if Sepoo could not be induced to accompany her.

Then she heard Sepoo's voice close behind her, protesting loudly that he would not take another step further. Kelly grinned with relief and quickened her pace.

For another twenty minutes Sepoo trailed along behind her, swearing that he was on the point of turning back and abandoning her, his tone becoming more and more plaintive as he realised that Kelly was not going to give in. Then quite suddenly he chuckled and began to sing.

The effort of remaining miserable was too much for him to sustain.

Kelly shouted a jibe over her shoulder and joined in the next refrain of the song. Sepoo slipped past her and took the lead.

For the next two days they followed the Tetwa River and with every mile its plight was more pitiful. The red clay clogged it more deeply.

The waters were almost pure mud, thick as Oatmeal porridge and there were dead roots and loose vegetation mixed into it already beginning to bubble with the gas of decay; the stink of it mingled with that of dead birds and small animals and rotting fish that had been trapped and suffocated by the mud. The carcasses were strewn upon the red banks or floated with balloon bellies upon the sullied waters.

Late in the afternoon of the second day they reached the far boundary of Sepoo's tribal hunting-grounds. There was no signpost or other indication to mark the line but Sepoo paused on the bank of the Tetwa, unstrung his bow and reversed his arrows in the rolled bark quiver on his shoulder, as a sign to the Mother and the Father of the forest that he would respect the sacred place and kill no creature, cut no branch nor light a fire within these deep forest preserves.

Then he sang a pygmy song to placate the forest, and to ask permission to enter its deep and secret place.

Oh, beloved mother of all the tribe, You gave us first suck at your breast And cradled us in the darkness.

Oh respected father, of our fathers You made us strong You taught us the ways of the forest And gave us your creatures as food.

We honour you, we praise you. . .

Kelly stood a little aside and watched him. It seemed presumptuous for her to join in the words, so she was silent.

In her book, The People of the Tall Trees, she had examined in detail the tradition of the forest heartland and discussed the wisdom of the Bambuti law. The heartland was the reservoir of forest life which spilled over into the hunting preserves, renewing and sustaining them.

It was also the buffer zone which separated each of the tribes from its neighbours, and obviated friction and territorial dispute between them.

This was only another example of the wisdom of the system that the Bambuti had evolved to regulate and manage their existence.

So, Kelly and Sepoo camped that night on the threshold of the sacred heartland. During the night it rained, which Sepoo proclaimed was a definite sign from the forest deities that they were aimenable to the two of them continuing their journey upstream.

Kelly smiled in the darkness. It rained, on average" three hundred nights a year in the Ubomo basin, and if it had not done so tonight Sepoo would probably have taken that as even more eloquent assent from the Mother and Father.

They resumed the journey at dawn. When one of the striped forest duiker trotted out of the undergrowth ahead of them and stood to regard them trustingly from a distance of five paces, Sepoo reached instinctively for his bow and then controlled himself with such an effort that he shook as though he were in malarial ague. The flesh of this little antelope was tender and succulent and sweet. Go! Sepoo yelled at it angrily. Away with you! Do not mock me! Do not tempt me! I am firm against your wiles.

The duiker slipped off the path and Sepoo turned to Kelly. Bear witness for me, Kara-Ki. I did not trespass. That creature was sent by the Mother and Father to test me. No natural duiker would be so stupid as to stand so close. I was strong, was I not, Kara-Ki? he demanded piteously, and Kelly squeezed his muscular shoulder. I am proud of you, old father. The gods love you.

They went on.

In the middle of that third afternoon Kelly paused suddenly in mid-stride and cocked her head to a sound she had never heard in the forest, before. It was still faint and intermittent, blanketed by the trees, but as she went on it became clearer and stronger with each mile until it resembled in Kelly's imagination the growling of lions on the kill, a terrible savage and feral sound that filled her with despair.

Now the River Tetwa no longer flowed, it was dammed with branches and debris, so that in places it had broken its banks and flooded the forest floor and they were forced to wade waist-deep through the stinking swamp.

Then abruptly, with a shock of disclosure, the forest ended and they were standing in sunlight where sunlight had not penetrated for a million years.

Ahead of them was such a sight as Kelly could not have conceived in her most hideous nightmares. She gazed upon it until night fell and mercifully hid it from her and then she turned away and went back.

In the night she came awake to find herself weeping aloud and Sepoo's hand stroking her arm to comfort her.

The return journey down the dying river was slower, as though she were burdened by her sadness and Sepoo shortened his stride to match her.

Five days later, Kelly and Sepoo reached Gondola.

Gondola was a site unique in this part of the forest. It was a glade of yellow elephant grass less than a hundred acres in extent. At the south end it rose to meet a line of forest-clad hills. For part of the day the tall trees threw a shadow across the clearing, keeping it cooler than if it had been exposed to the full glare of the tropical sun. Two small streams bounded this wedge of open ground, while the slope and elevation disclosed a sweeping vista over the treetops towards the northwest. It was one of the few vantage points in the Ubomo basin from which the view was not obscured by the great forest trees. The cool air in the open glade was less humid than that of the deep forest.

Kelly paused at the edge of the forest, as she always did, and looked out at the mountain peaks a hundred miles away.

Usually the Mountains of the Moon were bidden in their own perpetual clouds. This morning, as if to welcome her home, they had drawn aside the veil and stood clear in all their glistening splendour. The glaciated massif of Mount Stanley was forced upwards between the faults of the Great Rift Valley to a height of almost seventeen thousand feet.

It was pure icewhite and achingly beautiful.

She turned away from it reluctantly and looked across the clearing.

There was her homestead and laboratory, an ambitious building of log, clay plaster and thatch which had taken her almost three years to build, with a little help from her friends.

The gardens on the lower slopes were irrigated from the streams and fenced in to protect them from the forest creatures. There were no flowerbeds. The garden was not ornamental but provided the small community of Gondola with a large part of its sustenance.

As they left the forest, some of the women working in the garden spotted them and ran to greet Kelly, shrieking and laughing with delight. Some were Bambuti, but most were Uhah women in their traditional colourful long skirts. They surrounded her and escorted her up to the homestead.

The commotion brought a solitary figure out of the laboratory on to the wide verandah. He was an old man with hair as silver as the snows on Mount Stanley that faced him from a hundred miles away. He was dressed in a crisp blue safari suit and sandals. He shaded his eyes and recognized her and smiled.

His teeth were still white and perfect in his dark intelligent face.

Kelly. He held out both hands to her as she came up on to the verandah, and she ran to meet him. Kelly, he repeated, as he took her hands. I was beginning to worry about you. I expected you days ago.

it's good to see you. It's good to see you also, Mr. President. Come now, my child.

I am no longer that, at least not in Ephrem Taffari's view, and when did we last stand on ceremony, you and I? Victor, she corrected herself. I have missed you so, and I have so much to tell you. I don't know where to begin. Later. He shook his handsome grizzled head and embraced her.

She knew that he was over seventy years old but she could feel that his body had the strength and vigour of a man half that age. First let me show you how well I have taken care of your work during your absence. I should have remained a scientist rather than becoming a politician, he said. He took her hand and drew her into the laboratory, and immediately they were engrossed in technical discussion.

President Victor Omeru had studied in London as a young man. He had returned to Ubomo with a Master's degree in electrical engineering and for a short time had been employed in the colonial administration until he had resigned to lead the movement towards independence. Yet he had always retained his interest in the sciences and his learning and skills had always impressed Kelly.

When he had been overthrown in Ephrem Taffari's bloody coup, he had fled into the forest with a handful of loyal followers and sought sanctuary, with Kelly Kinnear at Gondola.

In the ten or so months since then, the settlement in the glade had become the headquarters of the Ubomo resistance movement against Taffari's tyranny, and Kelly had become one of his most trusted agents.

When he was not receiving visitors from outside the forest and planning the counter-revolution, he made himself Kelly's assistant and in a very short time had become invaluable to her.

For an hour the two of them were happily engrossed with slides and retorts and cages of laboratory rats. It was almost as though they were deliberately putting off the moment when they must discuss urgent and ugly reality.

Kelly's research was handicapped by inadequate equipment and shortage of expendable supplies. All of this had to be portered into Gondola, and since Kelly's field grant had been rescinded and Victor Omeru deposed, she had been even more restricted. Nevertheless, they had made some exciting discoveries. In particular they had been able to isolate an anti-malarial substance in the sap of the selepe tree. The selepe was a common plant of the forest that the pygmies used for the dual purposes of building their huts and treating fever.

Malaria was a resurgent menace in Africa where more and more frequently there appeared strains resistant to the synthetic prophylactics. Soon malaria might rank, once again, as the greatest killer on the continent, apart from AIDS. It seemed ironic that both these scourges should have their origin in the cradle of man himself, in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, where man had stood upright and taken his first uncertain footsteps into glory and infamy. Was it not possible that the ultimate cure for both these diseases might yet come from this same area of the globe? They both reasserted that hope, as they had done a thousand times before.

In addition to the malarial cure, there were the other possibilities that Kelly and Victor Omeru were considering. The one disease to which the Bambuti were susceptible was cancer of the pancreas. This was caused by some factor of their diet or environment in the forest. The women of the tribe used an infusion of the root of a vine that contained a bitter milky sap to treat the disease, and Kelly had witnessed some seemingly miraculous cures. She and Victor Omeru had isolated an alkaloid from the sap which they hoped was the active agent in the cure, and they were testing it with encouraging results.

They were using the same alkaloid to treat three of the Uhali men in camp who were suffering from AIDS. It was too soon to be certain, but once again the results were most encouraging and exciting. Now they discussed them avidly. This excitement and the pleasure of reunion lasted them through the frugal lunch of salads that they shared on the verandah of the thatched bungalow.

Kelly revelled in the joy of conversing with such a cultured and erudite man. Victor Omeru's presence had transformed her lonely isolated life at Gondola. She loved her Bambuti friends, but they came and went without warning, and though their simple happy ways were always a joy, they were no substitute for the stimulation of a superior educated mind.

Victor Omeru was a man she could respect and admire and love without reservation. As far as Kelly was concerned, he was without vice, overflowing with humanity and compassion for his fellow men, and at the same time with a deep and abiding respect and concern for the world in which they lived and the other creatures that shared it with them.

She saw in him the true patriot, completely devoted to his little nation. He was, in addition, the only African Kelly had ever met who was above tribalism. He had spent his entire political life trying to appease and ameliorate the terrible curse that was, in both their views, the single most tragic fact of the African reality. He should have been an example to the rest of the continent, and to his peers in the high councils of the Organisation of African Unity.

When, almost single-handed, he had obtained independence from the colonial administration, the preponderance of his fellow Uhah tribesmen had swept him into the presidential office and overturned at a single stroke the centuries of brutal domination by the proud Hita aristocracy.

The greatest crisis of his presidency had come within the very first days of independence. The Uhali tribe had turned upon the Hita in a savage orgy of retribution. In five terrible days, over twenty thousand Hita had perished. The mob had torched their manyattas.

Those Hita who survived the flames were hacked to death with hoes and machetes. The tools with which the enslaved Uhali had tilled the fields and hewn the firewood for their masters were turned upon them.

The proud Hita women, tall and stately and beautiful, were stripped of their traditional ankle-length robes, and the elaborately plaited locks in which they gloried were hacked roughly from their heads. They were herded naked before the jeering Ubali mob, and petted with excrement.

Some of the women were lifted struggling and naked and impaled upon the poles of the manyattas outer stockade.

The younger women and girls had been yoked between two of their own oxen, secured with rawhide thongs by each ankle.

Then the mob had urged the oxen forward and the girls had been torn apart.

Kelly had not been there to witness these atrocities. She had been a schoolgirl in England at the time, but the legend had become history of how Victor Omeru had gone out to plead with the mob and physically to interpose himself between them and their Hita victims. With the sheer force of his personality he had brought the slaughter to an end, and virtually saved the Hita tribe from genocide and extinction.

Nevertheless, thousands of Hita perished and fifty thousand fled for sanctuary into the neighbouring countries of Uganda and Zaire.

It had taken a major exercise of statesmanship over decades of wise government for Victor Omeru to cool the terrible tribal animosities of his people, to persuade the exiled Hita to return to Ubomo, to restore their herds and their grazing lands to them, and to bring their young men in from the traditional pastoral ways to education and advancement in the modern Ubomo nation he was trying to build.

In recompense for those terrible first days of independence Victor had always thereafter erred on the side of leniency towards the Hita tribe.

To demonstrate his trust and faith in them he allowed them gradually to take control of Ubomo's little army and police force. Ephrem Taffari himself had travelled abroad to complete his education on a special scholarship provided by Victor Omeru out of his own meagre presidential salary.

Victor Omeru was paying for that generosity now. Once again the Uhali tribe groaned beneath the Hita tyranny. As so often happens in Africa, the cycle of oppression and brutality had run its full course, but even now as they sat on the wide verandah of the bungalow, immersed in discussion, Kelly could still detect the suffering and concern for his nation and all his people in Victor Omeru's dark eyes.

It seemed cruel to add to his misery but she could no longer keep it from him. Victor, there is something awful happening up there, in the rivers of the forest, in the sacred Bambuti heartland. Something so terrible that I hardly know how to describe it to you. He listened without interruption, but when she had finished he said quietly, Taffari is killing our people and our land. The vultures smell death in the air and they are gathering, but we will stop them. Kelly had never seen him so angry before. His face was hard and his eyes were dark and terrible.

They are powerfUL, Rich and powerful. There is no power to match that of honest men and a just cause, he replied, and his strength and determination were contagious. Kelly felt her despair slough away, leaving her feeling renewed and confident. Yes, she whispered. We will find a way to stop them. For the sake of this land we must find a way.

beautiful. The name was appropriate, Tug Harrison conceded, as the RollsRoyce Silver Spirit left the littoral plain and climbed up into the green mountains. The road swept around a shoulder of one of the peaks and for a moment Tug gazed out across the broad Formosa Straits and fancied he saw the loom of mainland China lurking like a dragon a, hundred and more miles out there in the blue distance. Then the road turned again and they were back into the forests of cypress and cedar.

They were four thousand feet above the humid tropical plain and the bustle of Taipei, one of the busiest and most affluent cities in Asia.

The air up here was sweet and cool; there was no need of the Rolls's superb air-conditioning system.

Tug felt relaxed and clear-headed. It was one of the joys of having your own jet aircraft, he smiled. The Gulfstream flew when he was ready, wherever he wanted to go. There was none of the aggravation of large airports and throngs of the great unwashed multitude. No miles of corridors to traverse nor luggage carousels at which to play the guessing game of will it come or won't it, no surly customs officials and porters and taxi-drivers.

Tug had taken it in easy stages from London. Abu Dhabi, Bahrain, Brunei, Hong Kong, he had spent a day or two in each of those centres in all of which he had major games in play.

The stop-over in Hong Kong had been particularly worthwhile. The richest and more prudent of the Hong Kong businessmen were intent on moving out their assets and relocating ahead of the termination of the treaty and the reversion of the territory to mainland China. In the permanent suite which he kept at the Peninsula Hotel, Tug had signed two agreements which should net him ten million pounds over the next few years. When his chief pilot touched down at Taipei airport, ground control directed Tug's Gulfstream to taxi to a discreet parking billet behind the Cathay Pacific hangars and the Rolls-Royce was waiting on the tarmac, with the younest son of the Ning;

family to meet him.

Customs and Immigration, in the shape of two uniformed officials, were ushered aboard, bobbing and smiling, by his host.

They stamped Tug's red diplomatic passport and placed the in bond'seals on hisprivatebarand departed, all within five minutes.

In the meantime Tug's matched set of Louis Vuitton luggage was being transferred to the boot of the Rolls by a team of white-jacketed and gloved servants. Within fifteen minutes of touchdown, the Rolls whisked him out of the airport gates.

Tug felt so good that he was inclined to philosophise. He compared other journeys he had made when he was young and poor and struggling.

On foot and bicycle and native bus he had crossed and recrossed the African continent. He remembered his first motor vehicle, a Ford V-8

truck with front mudguards like elephant ears, smooth tyres that never ran fifty miles without puncturing, and an engine held together with balingwire and hope. He had been immensely proud of it at the time.

Even his first air flight on one of the old Sunderland flying boats that once plied the African continent, landing to refuel on the Zambezi, the great lakes, and finally the Nile itself, had taken ten days to reach London.

Truly to appreciate luxury it is necessary to have withstood severe hardship, Tug believed. The early days had been tough.

He had revelled in each one of them but, hell, the touch of silk against his skin and the Rolls upholstery under his backside felt wonderful and he was looking forward to the negotiations that lay ahead. They would be hard and without quarter, but that was the way he liked it.

He loved the cut and thrust of the bargaining table. He enjoyed changing his style to match each adversary he faced.

He could flash the cutlass or palm the stiletto as the occasion warranted. When called for he could shout and bang the table and curse with the same vigour as an Australian opal miner or a Texan rough-neck on an oil rig, or he could smile and whisper honeyed hemlock as skilfully as could the man he was now going to meet. Yes, he loved every moment of it. It was what kept him young.

He smiled genially and turned to discuss oriental nctsukes and ceramics with the young man who sat beside him on the pale green leather back seat of the Rolls. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek brought the cream of China's art treasures with him from the mainland inNing Cheng Gong was saying, and Tug nodded. All civilised men must be thankful for that, he agreed. if he had not done so, they would have been destroyed in Mao's cultural revolution.

As they chatted, Tug was studying his host's youngest son.

Even though he had not yet shown himself to be a force in the Ni g financial dynasty, and up until now had been overshadowed by his elder half-brothers, Tug had a full dossier on Cheng.

There was some indication that Cheng, even as the youngest son, was his father's favourite, the child of his old age, by his third wife, a beautiful English girl. As often happens, the admixture of oriental and Occidental blood seemed to have brought out the good traits of both parents. It seemed that Ning Cheng Gong had bred true, for he was clever, deviously ruthless, and lucky. Tug Harrison never discounted the element of luck. Some men had it and others, no matter how clever, did not.

It seemed that old Ning Heng H'Sui was bringing him on carefully, like a fine thoroughbred colt, preparing him for his first major race with patience and diligence. He had given Cheng all the advantages, without allowing him to grow up soft.

After his master's degree at Chiang Kai-shek University, Ning Cheng Gong had gone straight into the Taiwanese army for national service.

His father had made no effort to beat the draft on his behalf. Tug supposed that it was part of the toughening process.

Tug Harrison had a copy of the young man's military service record.

He had done well, very well, and had ended his call-up with the rank of captain and a job on the general staff. Of course, the commander of the Taiwanese army was a personal friend of Ning Heng H'Sui, but his selection would not have been entirely based on preferment rather than ability. There had been only one small shadow on Cheng's service record. A civilian complaint had been brought against Captain Ning, and investigated by the military police. It involved the death of a young girl in a Taipei brothel. The full report of the investigating officer had been carefully removed from Ning's service record and only the recommendation that there was no substance in the accusation remained, together with an endorsement by the Attorney-General that no charges be pursued.

Once again Tug Harrison scented the intervention of the Ning patriarch in this dossier. It increased Tug's respect for the power and influence of the family.

At the end of his national service, Ning Cheng Gong had gone into the Taiwanese diplomatic corps. Perhaps old Heng had not yet considered him ready to join the Lucky Dragon.

Once again young Cheng's progress had been meteoric, and he had been given an ambassadorship within four years, admittedly it was to a small and insignificant little African country, but by all accounts he had done well. Once again Tug had been able to obtain a copy of his service record from the Taiwanese foreign office. It had cost him ten thousand pounds sterling in bribes, but Tug considered it a bargain.

In this dossier he had again found some evidence of Cheng's unusual erotic tastes.

The body of a young black girl had been fished out of the Zambezi river only partially devoured by crocodiles. There was certain mutilation of the corpse's genital and mammary areas which had led the police to pursue further enquiries. They found that at the time the Chinese ambassador had been staying at a game lodge on the Zambezi south bank, near the girl's village. The missing girl had been seen entering Cheng's bungalow late on the evening before she disappeared.

She had not been seen again alive. This was as far as the enquiry had been allowed to run, before being quashed by a directive from the president's office.

Now the ambassador's term of office had run its course. He had resigned from the diplomatic service and returned to Taiwan to take up a position with the Lucky Dragon company, at last.

His father had given him the equivalent rank of vice-president, and Tug Harrison found him interesting. Not only was he clever but he was goodlooking to the Western eye. His mother's influence was discernible in his features; although his hair was jet black there were no epicanthic folds in his upper eyelids. His English was perfect. If Tug closed his eyes he could imagine he was conversing with a young upper-class Englishman. He was suave and urbane, with just the slightest perceptible streak of ruthlessness and cruelty in him. Yes, Tug decided, he was a young man with prospects. His father could be proud of him.

Tug felt the familiar stab of regret as he thought of his own feckless offspring, weaklings and wastrels all three. He could only console himself by believing that the fault must lie in their maternal line. They were the sons of three different women'all of whom he had chosen for their physical attractiveness. When you are young there is no reasoning with an erect penis, he shook his head regretfully, it seemed to inhibit the flow of the blood to the brain. He had married four women whom he would not have employed as, secretaries, and three of them had given him sons in their mirror image, beautiful and lazy and irresponsible.

Tug frowned at this shadow across his sunny mood. Most men give more thought and care to the breeding of their dogs and horses than they do to selecting a dam for their own children. Fatherhood was the only endeavour in his entire life in which Tug Harrison had failed dismally.

I am looking forward to viewing your father's collection of ivory, Tug told Cheng, putting unprofitable regret out of his mind.

My father will be pleased to show it to you, Cheng smiled. It is his chief delight, after the Lucky Dragon, of course. As he said it, the Rolls sailed around another hairpin and directly ahead stood the gates to the Ning estate. Tug had seen a photograph of them, but still he was not prepared for the actuality. They reminded him instantly of those gigantic garish sculptures in the Tiger Balm Gardens in Hong Kong.

The Lucky Dragon entwined itself around the gateway like a prehistoric monster, glittering with emerald-green ceramic tiles and gold leaf. Its talons were hooked and raised, its wings were spread fifty feet wide, its eyes glowed like live coals and its crocodile jaws were agape and lined with jagged fangs. My goodness!

said Tug mildly, and Cheng laughed lightly and deprecatingly. My father's little whimsy, he explained. The teeth are real ivory and the eyes are a pair of cabochon spinel-rubies from Sri Lanka. They weigh together a little over five kilos. They are unique and are valued at over a million dollars, hence the armed guards. The two guards came to attention as the Rolls slid through the gateway. They were dressed in paramilitary uniform with blancoed webbing and burnished stainless helmets similar to those worn by the honour guard at Chiang Kai-shek's tomb in Taipei. They carried automatic weapons and Tug Harrison guessed that they had other duties apart from guarding the Lucky Dragon's jewelled eyes. Tug had heard that young Cheng, using his military experience, had personally recruited these guards from the ranks of the Taiwanese marines, one of the elite regiments of the world, to protect his father.