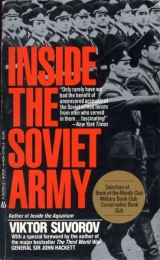

Текст книги "Inside The Soviet Army"

Автор книги: Viktor Suvorov

Жанр:

Публицистика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Each officer is responsible for the unit under his command from the very moment he takes it over. He is answerable for everything, even if he has only arrived four days – or three hours – earlier.

My company got the worst marks in the whole regiment. It did not matter that the next worst did not get many more – a wide rift appeared between us and all the other companies. The officers laughed at me, openly, and on the doors of the company's barrack-room there appeared the inscription `SUC = Suvorov's Uncontrolled Company'.

I reacted to all this mockery with a cheerful smile. Meanwhile, the companies which had taken between third and eighth places in the inspection were being put through `training' sessions by their officers. Ostensibly in order to correct the mistakes for which they had been marked down, they were taken off into open country and punished in the most brutal fashion, being made to run in gas masks and rubber protective clothing until they collapsed, unconscious. My company waited, mutely, for me to do the same. I did not delay. I drew up a training programme and had it approved by the regimental staff. I asked for the use of five armoured personnel carriers and for the help of a tank platoon, since my company had told me that they had had no instruction in working with tanks in action. Besides the tanks I applied for three blank rounds for the tanks' guns.

I took my company out to a training area and carried out ordinary training exercises with them. I explained anything they did not understand and then put them through their paces, but did not punish them in any way. Next I paraded them and called the oldest group of soldiers forward. `You have done your duty honourably, I said to them, `and you have followed a hard road. Today you have come to its end. Your last day of training in the Soviet Army is over. I thank you for all you have done. I cannot reward you in any way. Instead, allow me to shake you by the hand.

I went up to each man and shook him firmly by the hand. Next I went back to the centre of the parade and bowed stiffly to them – something which, according to the regulations, should only be done in front of a group of officers. Then, at my signal, the three tanks suddenly shattered the quiet of the autumn woods by firing the blank rounds, one after the other. This was so unexpected that it made the young soldiers flinch.

`The Army salutes you. Thank you. I turned to the sergeant-major and told him to march the company back to the barracks.

Some days after this, late one evening, dozens of rockets suddenly soared skywards over the camp, thunderflashes and practice grenades exploded and bonfires were lit. The demobilization order, signed by the Minister of Defence, had arrived. It had been expected for some days but it always arrives without warning. As soon as they hear about it, those who are to be demobilized treat themselves to a firework display. For several days before the order every regiment has a team searching for illegally held rockets, training grenades and anything which could be used for a bonfire. They find and confiscate a lot but they cannot discover everything, for each soldier has been carefully gathering and hiding materials which he can use for the `ceremonial salute'.

At the moment when the sky was suddenly lit up by blazing bonfires we, the officers, were in the middle of a Party meeting.

`Go and stop that! the regimental commander snapped. The company commanders leapt to their feet and ran off to stop the row which their unruly charges were making.

The only people left in the room were the regimental doctor, the finance officer, some technical and staff officers who had no soldiers under their direct command, and me. I stood quietly watching what was going on outside the window. The regimental commander looked at me in astonishment.

`The 4th Company are not involved, I said, in answer to his unspoken question.

`Is that so? he said, with some surprise and sent one of the other officers to check my claim.

It was indeed true that nothing was happening in the 4th Company. My tank salute had been a great deal more impressive than a few rockets and thunderflashes. The appreciation which I had shown had flattered the senior soldiers and had given them prestige and self-respect. While the barrack-rooms of all the other companies were being searched for anything which could be detonated or burned, they came to me to hand over a kit-bag full of odds and ends which they had collected and promised that they would not take part in the celebrations.

When the meeting was resumed, the regimental commander rebuked the other company commanders for their failure to prevent the outburst. Then he asked me to stand up and he commended me for the way I controlled my men and made them behave as I wanted. It was never his way to ask officers how they achieved results. However, his chief of staff could not restrain himself and he asked me to tell them how I had handled the senior soldiers in my company, so that everyone could learn from my example.

`Comrade Lieutenant-Colonel – I gave my orders and they were obeyed. From the outburst of good-natured laughter with which this was greeted, I knew that I had been accepted as an equal by the regiment's officers.

5

A Soviet officer is someone who has no rights whatsoever.

In theory, he knows, he must encourage those who are diligent and careful; he must punish the idle and the undisciplined. But the dictatorship of the proletariat has produced a state in which authority is too centralised to permit him to use either a stick or a carrot. He is allowed neither. He is not entitled either to punish or to reward.

On Sundays, the commander of a sub-unit is allowed to send 10 % of his NCOs and soldiers into town during daylight hours. This might seem to be a way of encouraging those who deserve it. In fact, however, although he may make a soldier a present of eight hours in this way, he cannot be sure that his battalion or regimental commander will not overrule him by stopping all leave. Besides, platoon and company commanders themselves are not enthusiastic about letting soldiers out of camp. If a soldier is checked by a patrol in the town and they find the slightest thing wrong, the officer who allowed the soldier to leave his barracks is held responsible. A commander, therefore, prefers to send soldiers off for the day in a group, under the eye of the political officer. This is the only way in which Soviet soldiers are allowed to go into a town in Eastern Europe and it is very frequently used in the Soviet Union, too. Since a Soviet soldier does not like being part of a convoy, he just does not bother to leave camp.

A company commander may hold a soldier under arrest for three days, but a platoon commander is not allowed to do so. However, by giving the company commander this right, the Soviet authorities have him by the throat; when the state of discipline in a unit is being assessed, the number of punishments is taken into account. For instance, arrests might average 15 in one company each month, but 45 in another. Clearly, say the powers that be, the first company must be the better one. Three soldiers might be punished in the first company and ten in the second. Again, this is a clear indication that the first company is in better shape. This attitude on the part of the authorities forces unit commanders to hush up or ignore disciplinary offences and even crimes, in order not to drop behind their competitors. As a soldier comes to understand the system, he begins to break the rules more and more frequently and ingeniously, confident that he will not be punished. Many attempts have been made to establish different criteria for assessing the state of discipline, but nothing has come of them. So long as the present system lasts, a commander will avoid handing out punishments, even when they are really called for.

Deprived of the right to punish or reward, an officer devises and imposes his own system. Thus, in one company, the soldiers will know that, if anything goes wrong, their night exercises will always be held when it is raining and will drag on for a long time. In another, they will know that they will have to spend a lot of time digging trenches in rocky ground.

Every commander gradually refines his system and he may eventually manage to avoid arrests and officially recognised punishments completely: he comes to be obeyed, without having to resort to them.

6

As well as denying the officer any legal method of controlling his charges, the system also forces him to develop his own methods of instructing them. Nor is he given any proper guidance in ways of ensuring the obedience of the men for whom he is responsible. Those who understand how to exercise power in the USSR guard their knowledge jealously: they certainly do not write textbooks on the subject. This is done for them by professors, who have never set eyes on a soldier in their lives. These professors have no power themselves – they may understand how it is acquired and retained, but their knowledge is entirely theoretical.

Nor will a young officer's colleagues pass on their experience on to him, for it has cost them too much to be handed out free. Anything which he learns at his military training college about relationships with his subordinates is the product of a professor's imagination and is of no practical value.

Once he graduates from his training college, the young officer suddenly finds himself in the position of a lion-tamer in a cage of lions, except that he knows no more about lions than that they belong to the cat family. Thereafter, the system of natural selection comes into operation – if you understand how to control your troops you will be accepted by the system; if not you will be relegated to the humblest of roles.

You learn the techniques of control from your own mistakes – and, unless you are a fool, from the mistakes of others. For there will be mistakes in plenty to be seen everywhere around you.

As an example, for several years the commander of the guard company of the 5th Army Staff punished any form of disobedience without mercy. His company was considered one of the best in the whole, huge Far Eastern Military District. His excellent record was noted and he was nominated for a place at an Academy, which would enable him to develop and to get ahead. With only a month left in command of the company, he found it impossible to retain his tight hold – his thoughts were centring more and more on the Academy. He changed his way of exercising command. One evening he invited all his sergeants to his office and gave them a tremendous party. The night turned out to be an unpleasant one for him – the sergeants, having had a lot to drink, nailed him to his office floor. The unfortunate man obviously had a poor knowledge of history; he had not grasped the simple fact that a revolution does not occur during a period of terror, but at the moment when that terror is suddenly relaxed. Historically, the examples of the French Revolution and of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 illustrate this principle; it will continue to operate.

A tough commander may take a disobedient soldier into the company office and beat him unmercifully. The soldier writhes on the floor for a while but then he gets to his feet, seizes a lamp from the table and hurls it in the officer's face. The soldier will be court-martialled but the officer will never again be able to control his company; the soldiers will laugh at him behind his back.

A young officer in front of his soldiers says to them, `If you get good marks at the inspection I promise you I'll… As an outside observer, you will see scepticism on the faces of the soldiers. You realise that the young Lieutenant is revealing one of his weaknesses, his desire to succeed. You can't always be kind to everyone, Lieutenant, and henceforth anyone whom you treat roughly will use this weakness against you. Everyone has a failing of some sort, but why let others realise it? They may prove to be anything but sympathetic. Just look at this scene and always try to remember the golden rule of controlling others – NEVER PROMISE ANYONE ANYTHING!

If you are able to do something for another person – do it, without having made any promises. From this first rule there follows a second – NEVER THREATEN ANYONE!

You can punish someone and, if you consider it necessary, you should do so. But promises and threats simply weaken your authority as a commander.

After some time you will come to understand the most important rules of all, one which you have never been taught – RESPECT YOUR SOLDIERS.

If a commander is invited by his soldiers to sit at their table, and if he accepts with the gratitude with which he would accept an invitation from his colonel, he is never likely to suffer at their hands. He can be sure that these soldiers will defend him in battle, even if it should cost them their lives. If a commander has learned to respect his soldiers (which means more than just showing them respect), he will suddenly realise, with some surprise, that he no longer needs informers in their ranks. His men will come forward of their own accord, tell him what is going on and ask for his help or protection.

A commander who respects a soldier can ask anything of him and can be confident that the soldier will carry out all his requests without pressure of any sort.

How Much Do You Drink In Your Spare Time?

1

The regimental parade takes place every day at 0800 hours. All the officers of the regiment must attend. Some of them will already have supervised reveille and morning PT, so they will have had to have arrived at the barracks before 0600. If it takes them an hour to get to the unit, they will have had to get up very early indeed. From 0800 to 1500 hours all officers take part in the training programmes. If you are a platoon commander you work with your platoon. If you are a company commander, you may work with your company sergeants or with one of the platoons – perhaps one of the platoon commanders is on leave, or perhaps you have no platoon commanders in your company. Battalion commanders, their deputies and battalion chiefs of staff, either work with platoons which have no commanders or check the training being carried out by platoon or company commanders. Checking training is a good deal easier than being checked yourself.

Officers have lunch between 1500 and 1600 hours. From 1600 until the late evening they are involved in officers' meetings or Party meetings, or they attend Komsomol meetings held in platoons, companies or battalions. During this period, after their lunch, officers also receive their own training – they pore over secret orders, they are shown classified films, and so forth. Meanwhile, the cleaning of weapons and combat equipment is being carried out in sub-units and, although this is supervised by sergeants, the officers are responsible for the condition of the equipment, and they therefore need to take a few minutes to keep an eye on what is going on. Finally, the officer will have to give seven hours of instruction next day and he must prepare for this. The colonel comes over from divisional headquarters to see what preparations we are making. He states that the preparation for a two-hour training period must include a trip out to the training area, the selection of a good spot for the work which is to be done there and briefing for the sergeants on the way the training is to be carried out. Thereafter, sub-unit commanders are to return to the camp and to work with their sergeants, studying manuals, regulations and recommendations. Next, they are to draw up plans listing the exercises which are to be carried out, to have these approved by their immediate superiors and targets, simulators, combat to prepare everything which will be needed – equipment, etc.

From what the colonel says, it appears that the preparations for a two-hour exercise should take at least five hours. We express agreement, of course, but to ourselves we think, `You can get stuffed, Colonel. I give seven hours' instruction a day. If I prepare for it in the way you are suggesting, I shan't even have time to go to the lavatory. No, my dear Colonel, I'm not going to spend five hours preparing this exercise. I'll spend five minutes. As quickly as I can, I write out the plan for the exercise and explain to my deputy how he must prepare for it. Everything will sort itself out tomorrow. If time is really pressing, during the Party meeting I get hold of the plans I prepared for last year's exercise and carefully alter the date. That means we can use last year's plan over again.

In the late evening comes the second regimental parade and by 2200 hours the officers who are not involved in night exercises have finished for the day.

What shall I do now? I am unmarried, of course. Anyone idiotic enough to get married while he is a lieutenant soon regrets it bitterly. He and his wife never see each other. The regiment has no married accommodation for junior officers and the relationship is doomed to failure. Any sort of private life is severely discouraged under Socialism, as a potential source of discontent and disunity. The resources available to the Armed Services are used to build tanks, not to put up married quarters for lieutenants. I realised this a long time ago and this was why I have not got married.

So, what shall I do with my spare time? The library is already closed, of course, and so is the cinema. I have no interest in going to the gymnasium – I have been rushing about so much today that I feel utterly exhausted. I'll just go back to the officers' quarters, where all the young bachelors live. There is a television set there but I already know that the whole of today's programme is about Lenin. Yesterday it was about the dangers of abortion and the excellence of the harvest, tomorrow it will be about Brezhnev and the harvest or Ustinov and abortion.

As I enter the living room, I am greeted with delighted cries. Around the table sit fifteen or so officers. They have just begun a game of cards and thick clouds of cigarette smoke hang over them already. I got no sleep last night so I decide to play just one round and then go to bed. A place is made for me at the table and a large glass of vodka put down beside me. I drink it, smiling at my companions, and push a large sum of money over to the bank. Here we go.

Some time after one o'clock, officers returning from night exercises burst noisily into the room, dirty, wet and worn out. They are found places at the table and someone brings them glasses of vodka. They got no sleep last night and decide to go to bed after just one round.

I lose money fast. This is a good sign – unlucky at cards, lucky in love. I assure the sceptics around me that losing is really a sign of good fortune.

Three hours later, the commander of a neighbouring company appears, having just inspected the night guard. He is greeted with delighted cries. Someone produces a full glass of vodka for him. We have already got through a good deal and we have begun to drink only half a glass at a time. The new arrival got no sleep last night, so he decides to leave after one round. The money flows quickly from his pockets – this is not a bad sign. At least anyone who loses money is not hiding it in his pockets. By tradition the loser buys drinks for everyone else. He does so. We decide to play one more round. A good sign… we've drunk all that… someone is coming… they're pouring out more drinks… another round… a good sign…

At six o'clock the clear notes of a bugle float out over the regiment-reveille for the soldiers. When we hear it we all get up, throw our cards on the table and go off to bed.

At 0700 hours a soldier, designated by me as the best in my company, has to wake me up. This is no easy task, but he manages it. I sit on my bed and gaze at the portrait of Lenin which hangs on the wall. What would our great Teacher and Leader say if he could see me in this state, my face puffy with drink and lack of sleep? My boots have been carefully cleaned, my trousers pressed. This is not part of the soldier's duties, but evidently the senior soldiers have given him orders of their own. They must like me, after all!

The doors and windows swim before my eyes. Here comes the door floating past. It is essential not to miss this and to choose the right moment to run through it, as it passes. Someone helpfully pushes me in the right direction. Along the corridor there are ten doors and they are all swimming past me. I must find the right one. Somehow I manage it and I step under the freezing, searingly cold shower. Then comes breakfast and by 0800 hours, glowing and rejuvenated, I am present at the regimental parade, in front of my Guards company. Hell, I've forgotten my map case, which has got the day's programme in it! But some one helpfully hangs it over my shoulder and the working day begins.

2

The Communist Party hopes that an unconquerable soldier can be produced – one who is more dedicated to Leninism than Lenin himself, who is an athlete of Olympic standards, who knows his tank, his gun or his armoured personnel carrier at least as well as its designer. But, for whatever reason this is not how things work out, so the Party comrades call for a detailed training programme for soldiers and NCOs to be prepared. This is presented to the Central Committee, but it does not produce better soldiers. Clearly, the junior commanders are not fulfilling their norms. Check up on them!

And check on us they do, each day and every day. Everything is checked and tested – by the staffs of the battalions, regiments. Armies and Military Districts, by the General Staff and by a whole mass of committees which it has set up, by the Inspectorate of the Soviet Army, by the Directorate of Combat Training of the Soviet Army, by similar directorates within Military Districts, Armies and divisions and by the Strategic Camouflage Directorate. In addition, tank crews are checked and tested by their own commanders, artillery personnel by theirs and so on. The first question any commanding officer is asked is – have you had experience of working with the infantry? If he has, he is sent off to test them, and then they come back to test his sub-unit.

Hardly a day passes without two or three checks. Every commission which arrives to carry out a check has its own pet subject. Can your men get into an APC in ten seconds and out again in the same time? Of course they can't, I reply.

That's bad, Lieutenant. Haven't you studied the plan? We'll make a note of that. Cursing, I take the one APC I have been allocated off to a clearing in the woods and make my first platoon climb in and out of it again and again as the plan requires. But soon another commission appears and wants to know whether my men can reach the standards laid down for high-speed crosscountry driving across broken terrain. No, I say, they can't. Well, Lieutenant, that's very bad. The assessors record this unsatisfactory finding and order me to begin training my drivers immediately, using the APC. I salute and recall the platoon which has been practising getting in and out of the APC, but I don't send the vehicle for driver-training. I'll keep the damned thing here with me, I decide. A new commission appears and asks their pet questions. How is your platoon getting on with firing automatic weapons from an APC? Not too well, I reply, but we are practising day and night. Here is the APC, there is the platoon and those are the machine-gun crews. The members of the commission smile and move on.

Two failures in one day. But no one is interested in the fact that I haven't got enough APCs. Even if I had, fuel would be short or there wouldn't be enough grenades or grenade launchers.

Two failures in one day – two failures to reach the norms prescribed in the programme for the training of NCOs and other ranks which has been approved by the Central Committee of the Communist Party!

I get back to my quarters late that evening, wet, dirty, tired and angry. I have had to do two night exercises, with two different platoons, straight off – two more teams have checked our performance and we've been awarded two more bad marks.

People make a place for me. Someone gives me a tumbler of vodka and tries to cheer me up – don't take it too seriously! I drink the vodka, but it is some time before it takes effect. So I have another. Now I'll play just one round of cards. But my anger does not evaporate. They pour me another drink. Another round of cards. A sure sign… Someone bursts through the door… they pour him a drink… they pour me a drink… another round… a good sign… At 0600 hours the bugle rouses us from the table. On it there are piles of cigarette ends, underneath it is a heap of bottles.

3

Gradually one gets used to checks and tests. One finds ways of dealing with the searching questions. I come gradually to the conclusion that it is quite impossible for me to meet the requirements of the training plan – for me or for anyone else. Its demands are too high and the training facilities are quite inadequate. Besides, the plan robs an officer of any initiative. I'm not allowed to give the company physical training if the plan shows that this is the period for technical training. During technical training I cannot show them how to replace the engine of a vehicle if, according to the plan, I should be teaching them its working principles. But I can't explain an engine's working principles because the soldiers don't understand Russian sufficiently well, so I am unable to do either one thing or the other. Meanwhile, the commissions keep arriving. In the evenings my friends tell me not to get upset. I do the same whenever I see signs that one of them is approaching breaking point. I hurry over and pour him a drink. I sit him next to me at table and thrust cards into his hand. Here, have a cigarette. Don't take it so hard…

After a few more months, I realise that it is essential for me to go through the motions of meeting the plan's requirements. However, I do not give all the drivers a chance at the wheel: instead I allow two or three of the best of them to use all the driving time which we are allocated. All the anti-tank rockets which we receive go to the three who perform best with the launchers; the other six will have to get by with theoretical training.

When a commission arrives, I tell them confidently that we are making progress in the right direction. Look at those drivers – they are my record-breakers – the champions of the company! The rest are coming along quite well, but they are still young and inexperienced. Still, we know how to bring them on. The commission is happy with this. And those are the rocket launchers. They could hit an apple with their anti-tank rockets (if you'd care to stand your son over there with an apple on his head). They are crack shots, the stars of our team! We'll soon have the others up to their standard, too. And these are our machine-gunners – three of them are quite superb! And this man is a marksman! And that section can get into an APC in seven seconds flat – which is faster than the official record for the Military District! How can the commission know that jumping into an APC is all that the section ever does, and that they have never been taught to do anything else?

People begin to notice me. They praise me. Then I am promoted to the staff. Now I walk about with a notebook, drawling comments – NOT very good! Have you not studied the Plan which the Party has approved? Occasionally I say – Not TOO bad. I know perfectly well that what I am seeing has been faked, that this is a handpicked team – and I also know the cost at which such results are achieved. But still I say Not TOO bad. Then I move off to the officers mess so that they can ply me with food and drink.

The difference between the work of a staff officer and that of a sub-unit commander is that on the staff you have no responsibility. You also get a chance to drink but don't have to drink too much. All you do is walk about giving some people good marks and others bad ones. And you eat better as a staff officer. Those pigs are meant for visiting commissions, after all – in other words, for us staff officers.

![Книга Soviet Military Power [Советская военная мощь] Издание шестое автора авторов Коллектив](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-soviet-military-power-sovetskaya-voennaya-mosch-izdanie-shestoe-284643.jpg)

![Книга Soviet Military Power [Советская военная мощь] Издание второе автора авторов Коллектив](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/no-cover.jpg)