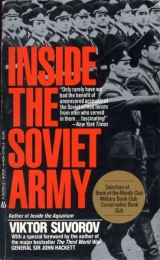

Текст книги "Inside The Soviet Army"

Автор книги: Viktor Suvorov

Жанр:

Публицистика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

If you can't, we'll teach you; if you don't want to, we'll make you

1

The column of recuits finally reaches the division to which it has been allocated. The thousands of hushed, rather frightened youths leave the train at a station surrounded by barbed wire, their heads are quickly shaven, they are driven through a cold bath, their filthy rags are burned on huge fires, they are issued with crumpled greatcoats, tunics and trousers that are too large or too small, squeaky boots and belts. With that the first grading process is completed. It does not occur to any of them that each of them has already been assessed, taking into account his political reliability, his family's criminal record (or absence of one), participation (or failure to participate) in Communist mass meetings, his height and his physical and mental development. All these factors have been taken into account in grading him as Category 0, 1, 2, and so forth and then allocating him to a sub-category of one of these groups. There will be no more than ten Category 0 soldiers in a whole motor-rifle division – they will go to the 8th department of the divisional staff. In each intake there will be two or three of them, who will replace others who are being demobilised, and who will themselves join the reserve. They have no idea that they are in this particular category or that files exist on them which have long ago been checked and passed by the KGB.

Category 1 soldiers are snapped up by the divisional rocket or reconnaissance battalions or by the regimental reconnaissance companies. Category 2 soldiers are those who are able to understand and to work with complicated mathematical formulae. They are grabbed by the fire-control batteries of the artillery regiment, of the anti-aircraft rocket regiment and of the self-propelled artillery battalions of the motor-rifle and tank regiments. And then there are the soldiers of my own arm of service, the tank crews – Category 6, thanks to the swine who do the planning in the General Staff. But nothing can be done about that – the army is enormous and bright soldiers are in demand everywhere. Everyone is after the strong, brave, healthy ones. Not everyone can be lucky.

A detachment is set up in each battalion, to handle the new intake. The battalion commander's deputy heads this and he is assisted by some of the platoon commanders and sergeants. Their task is to turn the recruits into proper soldiers in the course of one month. This is called a `Young Soldier's Course'. It is a very hard month in a soldier's life; during it he comes to realise that the sergeant above him is a king, a god and his military commander.

The recruits are subjected to a most elaborate and rigorous disciplinary programme; they clean out lavatories with their tooth-brushes, they are chased out of bed twenty or thirty times every night, under pressure to cut seconds off the time it takes them to dress, their days are taken up with training exercises which may last for sixteen hours at a stretch. They study their weapons, they are taught military regulations, they learn the significance of the different stars and insignia on their officers' shoulder boards. At the end of the month they fire their own weapons for the first time and then they are paraded to swear the oath of allegiance, knowing that any infringement of this will be heavily punished, even, perhaps, with the death-sentence. After this the recruit is considered to have become a real soldier. The training detachment is disbanded and the recruits are distributed among the companies and batteries.

2

Socialists make the lying claim that it is possible to create a classless society. In fact, if a number of people are thrown together, it is certain that a leading group, or perhaps several groups, will emerge – in other words different classes. This has nothing to do with race, religion or political beliefs. It will always happen, in every situation of this sort. If a group of survivors were to reach an uninhabited island after a shipwreck and you were able to take a look at them after they had been there only a week, you would undoubtedly find that a leader or leading group had already emerged. In the German concentration camps, no matter what sort of people were imprisoned together, they would always establish themselves in stratified societies, with higher and lower classes.

The division into leaders and followers occurs automatically. Take a group of children and ask them to put up a tent; do not put one of them in charge but stand aside and watch them. Within five minutes a leader will have emerged.

A group of short-haired recruits nervously enters an enormous barrack room, in which two, three or even five hundred soldiers live. They quickly come to realise that they have entered a class-dominated society. Communist theory has no place here. The sergeants split the young soldiers up by platoons, detachments and teams. At first everything goes normally – here is your bed, this is your bedside locker in which you can keep your washing-kit, your four manuals, brushes and your handbook of scientific communism and nothing else. Understand? Yes, sergeant.

But at night the barrack-room comes alive. The recruits need to understand that it contains four classes – the soldiers who will be leaving the army in six months, those who will go after a year, a third class who have eighteen months still to serve and, lastly, they themselves, who have a full two years to go. The higher castes guard their privileges jealously. The lower castes must acknowledge their seniors as their elders and betters, the seniors refer to inferiors as `scum'. Those who still have eighteen months to serve are the superiors of the new recruits, but scum, naturally, to those who have only a year to go.

The night after the new intake has arrived is a terrible one in every barracks: the naked recruits are flogged with belts, and ridden, bareback, by their seniors, who use them as horses to fight cavalry battles and then they are driven out to sleep in the lavatories while their beds are fouled by their elders and betters.

Their commanders know what is going on, of course, but they do not interfere; it is in their interests that the other ranks should be divided among themselves by barriers of real hatred.

The lowest class have no rights whatsoever. They, the scum, clean the shoes and make the beds of their seniors, clean their weapons for them, hand over their meat and sugar rations, sometimes even their bread to them. The soldiers who are soon to be released appropriate the recruits' new uniforms, leaving them with their own worn-out ones. If you are in command of a platoon or a company you are quite content with the situation. You order your sergeants to get something done – digging tank pits, for instance. The sergeants give the senior soldiers this job to do and they in turn hand it on to the scum. You can be confident that everything will be finished in good time. The senior soldiers will do nothing themselves but they will make each of the scum do enough for two or three men. You can take your sergeants off into the bushes and hand out your cigarettes; whatever you do, don't fuss. Wait until someone comes to report that the job has been done. This is your moment: appear like the sun from behind the clouds, and thank the senior soldiers for their hard work. I assure you – both the senior soldiers and the scum will love you for it….

Six months pass and a new consignment of scum joins your sub-unit. Now those who suffered yesterday have a chance to vent their rage on someone. All the humiliations and insults which they have suffered for six months can now be heaped on the newcomers. Meanwhile those who still insult and beat them up continue to be regarded as scum by their own superiors.

These are the circumstances in which a soldier begins to master the rudiments of the science of war.

1,441 Minutes

1

`Roll on my demob! `I wish you all a speedy demob – make sure you deserve it! They've taken everything else away, but they can't take my demob! `Demobilization is as inevitable as the collapse of capitalism. These are sentences you will see scribbled on the wall of any soldiers' lavatory. They are cleaned off every day but they are soon back again, in paint which is still wet.

Demobilization comes after two years' service. It is the day-dream of every soldier and NCO. From the moment a recruit joins the army, he begins to cross off the days to his demob. He lists the days left on the inside of his belt or ticks them off on a board, a wall, or on the side of his tank's engine compartment. In any military camp, on the backs of the portraits of Marx, Lenin, Brezhnev, Andropov and Ustinov you will find scores of inscriptions such as `103 Sundays left to my demob', accompanied by the appropriate number of marks, carefully ticked off one by one in ink or pencil. Or `730 dinners to my demob' and more marks. Or, frequently `17,520 hours to my demob' or, even more often, `1,051,200 minutes to my demob'.

A soldier's day is split up into a number of periods of so many minutes each and this makes it most convenient for him to calculate in minutes. The Soviet soldier reckons that his day lasts just a little bit longer than it does for any other inhabitant of the planet, so in his calculations he reckons that a day contains 1,441 minutes – a minute longer than it does for the rest of us.

A minute is the most convenient division of time for him, although he has to count in seconds, too.

2

The soldier's second day-dream, after his demobilization, is to be allowed to sleep for 600 minutes. Theoretically, he is allowed 480 minutes for sleep. Of course, one of the scum gets only half this: as he moves into a higher caste and becomes more senior he sleeps longer and longer. A month before his demobilization a senior soldier hangs a note above his bed `Do Not Tilt! To be Carried Out First In Case Of Fire.

Reveille is at 0600 hours. Wake up, jump out of bed, trousers and boots on, run outside for a rapid visit to the lavatory, sprint to the door, which is jammed with people, another sprint and you are on the road outside, past the sergeants who are lying in wait for the `last on parade'. By 0605 the company is already moving briskly along the roads of the military camp. In rain and wind, in hail and snow – just boots and trousers, chests bare. Running and PT until 0640 – 35 minutes of really hard physical exercise.

Then the company goes back to the barrack-room with 20 minutes to wash and make beds. During this time the scum have to make both their own beds and those of the senior soldiers. At 0700 there is morning inspection; the sergeant-major spends half an hour on a rigorous check of the company's general tidiness, haircuts, contents of pockets, etc. After this, the company falls in and moves off, bawling a song and marching in time to it, to the dining hall. An attentive observer would notice that the number of soldiers in the company is now greater by a quarter than it was during the PT parade. Actually, when the orderly first shouted, `Company. On your feet! at reveille, by no means everyone jumped hastily out of bed. The most senior of the soldiers, those with only six months to go before their demob, get up unwillingly and slowly, stretching, swearing quietly to themselves, not joining in the rush to the lavatory or tearing off to the parade. While the rest of the company marches round the corner, they go quietly about their own affairs. One may stretch out under his bed to sleep for another half hour, others doze behind the long row of greatcoats, which hang from pegs by the wall, and the rest may tuck themselves away somewhere at the back of the barrack-room by a warm pipe from the furnace-room. Whatever they choose to do, they don't turn out for PT with the rest of the company. They keep an eye out for the patrolling duty officers, quietly changing their hiding places if he approaches. Eventually they go and wash, leaving their beds to be made by the scum.

The Soviet Army serves a meagre breakfast. A soldier is allowed 20 grammes of butter a day, but since, theoretically, 10 of these are used for cooking, there are only 10 grammes on his plate. With this, for breakfast, he receives two slices of black bread, one of white, a bowl of kasha and a mug of tea, with one lump of sugar.

Butter and sugar are used as a sort of currency, with which to placate one's seniors for yesterday's mistakes or for some piece of disrespectful behaviour. They are also used as stakes for bets so that many of the soldiers have to hand over their breakfast butter or sugar – or both – to those who have been luckier than them at guessing the results of football or hockey matches.

There is not much bread, either, but if a soldier somehow manages to get hold of an extra slice, he will always try to make his tiny portion of butter cover it too, so that it is bread and butter rather than just bread that he is eating. Several soldiers from my company once spent a day working in the bakery and, of course, they helped themselves to a few loaves, which they shared with the other members of their platoon. Each of them had ten or fifteen slices of bread to spread his butter on and was able to eat as much as he wanted, for the first time for months. But there was very little butter indeed for each slice. I was not far away, and, seeing how they were enjoying themselves, I went over and asked how they could tell which of the slices had butter on them. They laughed and one held a piece of bread above his head and gently tilted it towards the sun. The answer became clear – a slice on which there was even the smallest scraping of butter reflected the sunlight.

3

At 0800 hours there is a regimental parade. The deputy regimental commander presents the regiment for inspection by the commander. Then the day's training, which lasts for seven hours, begins. The first hour is a review period, during which officers from the regimental or divisional staffs test the extent to which officers, NCOs and soldiers are ready to proceed with the forthcoming day's work. Soldiers are questioned on what they learned during the previous day, what training they received and what they have memorized. For me, as for any commander, this was a most uncomfortable hour. During this review period, too, orders by senior commanders from regimental level up to that of the Minister of Defence himself are read out, together with the sentences imposed on the previous day by Soviet Army military tribunals – outlines of cases involving five to ten years' imprisonment, and sometimes death sentences.

If the review period ends early, the rest of the hour is used for drill. After this come three periods, each of two hours. During these each platoon works in accordance with a training schedule which covers the following subjects:

Political training

Tactics

Weapon training

Drill

Technical training

Weapons of mass destruction and

Defence against these

Physical training

The number of hours spent on each subject varies considerably, depending on the arm of service and the Armed Service in which the soldiers are serving. However, the general plan of work is the same everywhere – a review period, drill and then six hours of work on the subjects listed above in accordance with individually arranged training schedules.

Ninety-five per cent of all work, except for political training, is done out of doors, rather than in classrooms – in the open country on ranges, in tank training areas, in tank depots, etc. All periods, except for political training, involve physical work, which is often very strenuous.

For instance, tactical training may involve six hours digging trenches in blazing sun or in a hard frost, high-speed crossings of rivers, ravines, ditches and barricades, rapid erection of camouflage – and everything is done at the double. Instruction in tactics is always given without equipment. Thus, a tank crew is told to imagine that they are in a tank, attacking the enemy `on the edge of the wood over there'. Having run to the wood, the crew returns and the tank commander explains the mistakes they made – they should have attacked not on the crest of the hill but in the gully. Now, once again… Using this system of instruction, you can quickly teach a crew, who may be unable to understand complicated explanations, how an enemy should be attacked, and how to use every hollow in the ground to protect their own tank in battle. If they don't, well they just run off again, and again, and again for the whole six hours if necessary.

Weapon training involves study of weapons and of combat equipment. But you should not imagine that a platoon sits in a classroom, while the instructor describes the construction of tanks, guns and armoured personnel carriers.

The sergeant shows a young soldier an assault rifle. This is your personal weapon. You strip it like this. You are allowed 15 seconds to do this. I will show you and then we will practise it – do it again – and again – now do it with this blindfold. And again… This is our tank. It carries 40 shells, each of which weighs between 21 and 32 kilogrammes, according to type. All the shells are to be loaded from these containers through this hatch into the tank's ammunition store. You've got 23 minutes to do this. Go! Now do it again – and again – and again.

Any process, from changing a tank's tracks or its engine to running in rubber protective clothing during CW training, is always learned by practical experience and practised again and again until it becomes entirely automatic, every day, every night for two years. So many seconds are allowed for each part of the operation. Make sure you do it this time: if you don't you'll have to practise it again and again and again, at night, on Sundays, on Sunday nights.

Exceptional physical strain is put upon Soviet soldiers. During his first days in the army a young recruit loses weight, then, despite the revolting food, he begins to put it on, not as fat, but as muscle. He starts to walk differently, with his shoulders back, a mischievous twinkle appears in his eye and he begins to acquire self-confidence. After six months, he begins to develop considerable aggression, and to dominate the scum. In his battles with the latter, he wins not only because of tradition, or the support of his seniors, his NCOs and officers – he is also physically stronger than they are. He knows that recruits coming into the army are far weaker than he is – he has six months of service behind him. Within a year he has become a real fighting-man.

A Soviet soldier is forced to adapt to circumstances. His body needs rest and he will find a thousand ways to get it. He learns to sleep in any position and in the most unlikely places. Don't ever think of giving an audience of Soviet soldiers a lecture with any theory in it – they would fall asleep at your very first words.

At 1500 hours the platoon, exhausted and dripping with sweat, returns from training, and tidies itself up. Hastily, everyone cleans boots, washes, puts things right – at the double, all the time. Dinner parade – they march off, singing, to the dining hall and spend 30 minutes there over disgusting, thin soup, semi-rotten potatoes with over-salted fish and three slices of bread. Hurry, hurry. `Company, on your feet! Fall in! Dinner is over. They march off, singing, to the barrack-room. From 1600 to 1800 they clean weapons, service equipment, clean the barracks and tidy the surrounding area. From 1800 to 2000 `self-tuition'. This means training which is devised not by the divisional staff but by the sergeants. `50 press-ups. Now do it again… You didn't make much of a job of loading those shells. Try it again… Now once more… The time you took to run three kilometres in your respirator was poor. Go and do it again.

From 2000 to 2030 – supper. Kasha or potatoes, two slices of bread, tea, a lump of sugar. `Butter? – you had that this morning. After supper a soldier has 30 minutes of free time. Write a letter home, read a paper, sew up a senior soldier's collar-lining for tomorrow's inspection, clean his boots until they gleam, iron his trousers.

At 2100 hours there is a formal battalion, regimental or divisional parade. Evening roll-call, a run-through of the time-table for tomorrow and of the results of today's training, more sentences imposed by military tribunals and then an evening stroll. This takes the form of 30 minutes of drill, with time kept by drum-beat, and training songs, yelled out by several thousand voices. At 2145 the soldier reaches the barracks again, washes, cleans his teeth, polishes and cleans everything for next morning. At 2200-lights out. For those, that is, who are not on night exercises. The timetable makes provision for 9 hours of night training each week. No allowance is made for loss of sleep. These night exercises can, of course, go on for any length of time. And those who are not on night exercises may be got out of bed at any moment by a practice alert.

4

Saturday is a working-day in the Soviet Army. What makes it different from other days of the week is that the soldiers have a film-show in the evening. No – not about James Bond, but about Lenin or Brezhnev.

Sunday is a rest-day. So reveille is at 0700 hours, instead of 0600. Then, as always, morning toilet, PT, breakfast. And then free time. This is what the political officer has been waiting for. There is one of these `Zampolits', as they are called, in each company, battalion, regiment and so on. The Zampolit can only work with the soldiers on Sundays, so his whole energy is devoted to that day. He arranges tug-of-war competitions and football matches – more running! He also gives lectures about how bad things were before the Revolution, how good life is nowadays, how the peoples of the world groan under the yoke of capitalism and how important it is to work hard to free them. In some regiments the soldiers are allowed to sleep after dinner. And how they sleep – all of them! On a bright sunny Sunday, sometimes, a division looks like a land of the dead. Only very occasionally is a single figure – the duty officer – to be seen walking around. The silence is astonishing and unimaginable at any other time. Even the birds stop singing.

The soldiers sleep on. They are tired. But the Zampolits are not tired. They have been resting all week and now they are bustling about, wondering what to organise next for the soldiers. How about a cross-country run?

Sunday does not belong to the Soviet soldier, and so he reckons, reasonably enough, that this day, too, lasts 1,441 minutes instead of 1,440.

![Книга Soviet Military Power [Советская военная мощь] Издание шестое автора авторов Коллектив](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-soviet-military-power-sovetskaya-voennaya-mosch-izdanie-shestoe-284643.jpg)

![Книга Soviet Military Power [Советская военная мощь] Издание второе автора авторов Коллектив](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/no-cover.jpg)