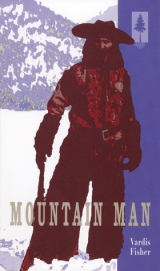

Текст книги "Mountain Man"

Автор книги: Vardis Fisher

Жанры:

Вестерны

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Suddenly Sam turned from a beast he was skinning, and standing straight and tall, looked at the woman, his face a wonder to behold. It was as if there had suddenly entered his mind the words of various wise men, for whom there had been in the human female a natural superiority—her greater compassion, for one thing, that strove to succor the helpless and defenseless; her greater devotion, for another, that could oblige her mother-heart to sit for days and nights by the graves of her children, without food or drink, and probably (Sam would have said) without sleep. The wonder in his face was this larger view of women, to which this woman had brought him. Did she intend to sit here all fall, winter, and spring? he asked her. Would she go with him to find a boat or a wagon train? Did she not think that the Almighty up there, looking at her, would want her to shake out of this, and eat and sleep and go on living? "I’ll tell you," he said. "I’ll boil a pot of this fat buck and have a cup of broth with you."

In a few minutes he had ten pounds of venison steaming over one fire and a whole loin slowly roasting in the embers of another. When the boiled meat was tender he took to her a tin cupful of broth and a slice of hot loin on a tin plate; and these, kneeling, he offered to her, saying. "You have to eat. These hot deer drippins will warm your innards and make the world look better." He drank broth and ate raw liver and about three pounds of loin. He then filled his pipe and scanned the earth around him. It was foolish to think that this woman could long endure here, if the redmen resolved to take her scalp and weapons; it would be best to spread the word to all the free trappers that she was here, who would then spread it among all the Indian tribes, with the warning that if a redman took her scalp the vengeance of the mountain men would demand ten scalps for every hair of her head. The skulls out there on the stakes were the only language the redmen could read.

While Sam puffed his pipe and looked over the scene his contempt for the red people and some of their ways fanned his emotions until he was in a red heat of anger. The contempt, on both sides, had its beginning in the earliest association of redmen and white, and became a law of their lives as fixed as the redman’s death chant or the whiteman’s fatalism. The redmen could not understand why the whitemen gave priceless treasure for the pelts of beaver and otter, which for them had little value in a land where beaver were as thick as trees. The whitemen could not understand why the redmen were eager to trade a pile of pelts for a piddling trifle—a handful of blue beads, a piece of glittering metal. "He’s like the coon," Windy Bill said. "If it shines he’s gotta git his paw on it." Each thought the other fantastically stupid, and his low opinion of the other’s mind and values gave zest to slaughter and scalping. If redmen had set four white skulls on stakes mountain men would have laughed loud in the heavens. If Wind River Bill had been here to view Sam’s handiwork he would have said, "I reckon that-air will send them heller-skelter torst their tipees." To the pine and juniper hills and the wind rising in the north Sam said he guessed it would, and was satisfied with his labor.

It was time to be off but he was reluctant to go. In a moment of mad male gallantry he had considered digging a well by the shack, but knew that he would have to dig to river level, a depth of a hundred feet. Should he ask her to go on a journey with him, not to be his night woman (he was not a lustful man, nor one to take advantage of the female’s helplessness) but to get her mind off her grief. But so far as he could tell, she had not accepted him as a friend. He was not sure that she was conscious of him, or of the wolves howling in the night, or of the flowing-through-mountains sound of the river’s waters. He was put out with himself because he lingered: it was the Almighty’s problem, not his. The evening of his eighth day here he forced himself to face her; and after looking down at her bowed head for several minutes he knelt and kissed her dusty brown hair, and said, close to her ear, "There’s a lot of meat for you in the house. I’m off to get a wife now, but I’ll be back soon."

He mounted his stallion and headed south up the river, but four times he stopped and looked back. In this situation a man simply didn’t know what to do. If she was determined to sit by the graves and die he guessed she had the right to die alone. No beast, no man, would molest her. His journey lay not over to the Bighorns, the Powder, Tongue, and Wind rivers, but to the Gallatin Gateway, the Beaverhead, and Chief Tall Mountain, whose oldest daughter, blooming into womanhood, was as lovely as the spring song of the bluebird or the alpine lily at the edge of a melting snowbank. A wife, he knew, was a huge armful of responsibility, and responsibility was the disease in man. But he was lonely, and twice as lonely after leaving the

woman by the graves.

The fourth time he looked back he saw her come through the doorway and, stand by the cabin. She seemed to be looking round her. If the lark at heaven’s gate had sung for him alone he could have been no more gladdened. She would be all right! She had only been waiting for him to go away! Dear God, be kind to her! He saw her go over and sink to the earth between the graves. Dear God, be kind to her! Feeling that all was well, he waved to her, knowing that she could not see him, and then rode till midnight, and was thirty miles from her and her gruesome sentinels when he found a thicket in which to hide and sleep. Dear God, he thought, kissing his hand and pretending that it was this mother’s cheek, dear God, be kind to her.

4

HB WAS TEN miles beyond the woman’s sight when she heard her name called. "Kitty!" the voice said. It was her husband’s voice and that was her husband’s name for her. Getting to her feet, she looked round her with wild staring eyes and then began to run toward the massacre site. "John!" she called as she ran. After two hundred yards she stopped and looked in all directions, and listened; and called again: "John!" She felt that he was present and not far away. She was staring at the tree where she had seen him bloody and bent when she thought of her children. Turning, she ran back up the hill, expecting to find them sitting by the graves; and when she saw only the two mounds she looked at them, listening, her heart in her throat. "John?" she said. She went to the shack and looked inside. She looked toward the river, and remembering that their camp was down there, she ran toward it, in the ungainly wavering way of one who had had no food and water and almost no sleep for many days and nights. She looked back under the lean-to that her husband and sons had built but nothing was there. She looked round her and softly called: "John?" She listened, but there was only the river’s waters. Like a woman waiting for the man who would surely come, she stood by the lean-to for an hour, looking and listening.

She had no weapon with her, not even a knife. It was as if in that hour of utter loneliness and loss she gave up to heaven all weapons and all sense of weapons for she would now go defenseless to the river for water, to the bottomlands to look for food, to the hilltops to look for her husband. Standing by the lean-to and trembling with hope, her eyes wide open and staring, her ears open to all things between earth and heaven, she went back up the hill and stood by the graves. She had seen but had not recognized the four skulls; and an hour later, when she walked north and east over the hills, looking for her husband, she passed close to one of the Indian heads but seemed not to see it. Her sense of what had happened since that morning was only a faint pallor; it had all been dimmed by sorrow and fatigue and soul sickness. She went almost a mile into the hills, pausing now and then to call softly, to look round her and. listen; and then returned to the graves. She would go again, and again—to the lean-to, to the massacre tree; for he would call to her again and again, in the weeks to come. In the dead of night his voice would arouse her from shallow sleep and she would sit up, saying, "John?" He would call to her as August passed and September came in, and the aspens and cottonwoods turned golden.

Now and then she saw him in the distance and ran toward him. She knew that someday she would find him. A rational mind would have seen here a world unlike the one Kate saw. Standing by the graves, he would have looked north or south and seen the long irregular line of trees that hid the river. In the west, beyond the line, he would have seen hills that looked empty and dead, but for their thin dress of stunted cedar. Looking the other way, to the east, he would have seen the same kind of hills, and sky pallor and thin gray loneliness; and in all directions he would have sensed an expanse of silence and emptiness. Kate saw none of all that, or saw it so indistinctly that it was only the haze upon the clear world in which she lived.

The world in which she was to live her senses did not build at once; it was evoked by prayer and longing and hope, by dreams and visions, and it came into being slowly, out of heaven. For God was kind to her. There had to be this evocation, or there had to be madness that would have thrust her down to the level of beasts. Without her vision she would have wandered away and been killed, by wolf or Indian; or she would have starved or died of cold when winter came. Within a few months the roaming free trappers, having learned her name, would be talking by campfires of that crazy Bowden woman. She would never go home, she would live and die there by the graves. It was enough to make a man feel cut loose from himself and pulled down in deep water like a gone beaver. It was enough to make a man crawl into a deep thicket and cry like a child.

Legend was to say that John Bowden was there. His wife knew he was there; she saw him now and then, always at a distance, always smiling at her, his smile and his eyes saying that he was all right, all of them were all right, and someday they would be together again, with God. The time was to come when she would no longer call to him or run toward him. With a smile she would answer his smile, her eyes saying yes, it was so, they would be together again, they were together now.

Her most remarkable transformation of loss and loneliness enveloped her children. About three weeks after Sam rode away she looked at the graves and thought they needed a loveliness. Up and down the river she searched for wild flowers and found a few, but the plant that caught her eye was a species of sage, with a soft greenish-gray beauty all its own. With the shovel she took up a few of these plants without disturbing the earth that hugged the roots, and set them in holes at the south end of her tiny cemetery. She carried water from the river to give them drink. They flourished, and the time came when she had a garden, there on the barren hillside. The time came when she no longer knew exactly where the graves were. The time was to come when there would pass from her soul all memory of them and all need of them; for her children would no longer be in the earth but above it, smiling at her use—their father smiled.

The first vision was in a cold moonlit night, before the fading memory of the graves had completely left her. She had come from the shack and walked over to the graves, to kneel there and pray, when suddenly she was transfixed by the dim heavenly figure kneeling behind a clump of sage, or within it, or of it—she would never be able to tell where it was. This vision was of her daughter. It was not her daughter as she had actually been in life: this girl in the sage, or behind it, was so ethereal, so like a filmy moonglow, so dreamlike, so like a pale and delicate part of heaven, that Kate, looking at her, held her breath and thought how sweet it was to die. After long moments she moved toward it, only to see it fade and pass away, not quickly, but as a moving cloud dissolves and fades. Horrified, she retreated, and as slowly as it had vanished the vision returned, coming out of nothing into an exquisite apparition that was looking at her and smiling, and gently inclining its head, as though moved by a breeze. Kate had eyes only for her until, looking at other plants, she saw her sons; and they were exactly of the same heavenly moonglow radiance, behind a sage, or in it or of it. Like the daughter, they were looking at her and smiling, and gently moving their heads a little up and down.

All night until the moon was gone Kate filled her soul with the three faces. She would have been worse than mad to doubt that her children were there. If she shut her eyes she did not see them. If she advanced too far toward them they simply dissolved into the night and there were before her only the sage plants. But every time without fail they returned when she withdrew and they smiled at her in the same angelic way. They looked to her like exquisitely scented and clothed beings just down from heaven. The eyes of all three smiled steadily into her eyes, not to probe her soul but only to reassure her. "My darlings!" she would whisper to them, smiling, and like them moving her head up and down.

They did not come in the daytime or when there was no moon; and if the moon was only a slice or a quarter, or was wan, they did not come. Her husband came at any time of day or night in any season. She might see him riding a horse and leading a packhorse, going up or down the river; and he always waved to her and she waved to him. She knew that he had a man’s work to do. Or he might come at night when she was asleep; in the morning she would End by her door, or just inside it, a leather sack filled with things for her, and in another skin, jerked elk or buffalo. She would find powder and ball, needles, thread, flower seeds, sugar, salt, coffee, flour; and once there was a shining new knife, and time and again there were tanned skins, medicines, such as camphor, aloes, salves, demulcents, baking soda, and a dress or a pair of shoes.

She never fired her gun to frighten away the killers. She came to think of her world as a world without hunters and hunted, though the wolves now and then forced her to take another view of it. It was in early November of her first autumn here that she was awakened one night by piteous crying. Her first thought was for her children; seizing the axe, which she kept by her bed, she rushed outside. There was no moon but it was not a dark night. She listened. The cry came again; it was continuous now, a bleating begging cry of pain and torment, and it was not toward the river but somewhere back of her house. Running toward it, she stopped when she saw the three large tawny forms. On the long journey with her husband and children she had seen the big gray wolf; during the past weeks she had seen these beasts, insolent, fearless, tongues lolling, sharp eyes looking for something to kill.

Convinced that they were killing out there in the night, she did not hesitate but ran against them as she had run against the Blackfeet warriors; and she was so strong and agile, and so borne up by rage, that she was on the wolves and had half severed a head before they knew she was there. The other two then leapt away, incredibly swift, and with a cry wilder than their own Kate chased them into the night. Returning, she saw that the victim was a buffalo calf: the wolves had been eating from the top of the flanks, where they had made a gaping hole to get at the liver, loin, and kidneys. The poor thing was not dead and it was still crying for its mother.

Kate did not know—and God would spare her the knowledge—that the wild-dog family ate its victims alive, if the victims had the stoutness and pluck to keep breathing until the enemy’s hunger was appeased. Many a buffalo still walked the prairies that had had a wolf’s meal taken out of it. Depending on the strength of his hunger, or his mood, the wolf would rip and tear with its long sharp teeth, usually into the side or back to get at the liver; and often it devoured all the tender flesh along the lower spine before its victim died. Or it might open a hole in the belly. If it had a taste for hams it might eat most of the flesh off a hindquarter. Many a buffalo or elk calf or yearling survived the rending of its flesh and the drinking of its blood, and lived as a cripple, hideously scarred. Kate would never know that this deadly killer which, in a pack, could put the monstrous male grizzly to flight, often teased and tortured, or killed, for the wanton sport of it. Three or four of them would isolate a buffalo yearling from the herd and chase the terrified and bawling creature back and forth in the tall prairie grass, nipping at it, tearing gaping wounds in it, spending perhaps an hour or more in frolic and sport, before the beast’s agony was ended.

The calf at which Kate looked was not dead but she knew it must die. Pulling the dead wolf away and kicking savagely at it, she examined the calf’s wounds. When she saw that a flank had been torn open and a part of the guts pulled out she smote the forehead a hard blow and put a compassionate hand on the shuddering flesh as it died.

Kate’s new world was indeed a world of the hunters and the hunted. She saw hawks strike and kill ducks in mid-air. In the river bottom when looking for roots and berries she saw the nestlings of thrush and wren, bluebird, mourning dove, and lark impaled on thorns in a shrike’s old butcher shop. She came to imagine things which she never actually saw or heard, and after a while it became a habit with her to seize the axe and rush into the night, and tremble with outrage while listening and looking. She would hear, as time passed, other animal children crying under the rending teeth, and none more frequently than the rabbit. Her life would be haunted by the scream of the cottontail, seized by a falcon, or of the big hare, overtaken by a wolf.

She would never fully understand that she lived in a world of wild things, many of which were killers—the weasel, mink, hawk, eagle, wolf, wolverine, cougar, grizzly, bobcat—these were ferocious and deadly; but the rabbit, deer, elk, buffalo, antelope, and many of the birds killed nothing, but themselves were slain and eaten by the thousands. In her life in a small Pennsylvania town Kate had barely known that there was this kind of world. She had known that there were creatures that killed other creatures, men who killed men, for either God or passion; but the world here was one in which to kill or to escape from the killer was the first law of life.

Her female feelings about these things would have astonished most of the mountain men. Windy Bill might have said, "Well, cuss my coup! Does she think Chimbly Rock is a church steeple?" Bill Williams, looking sly and secretive in all the seams and hollows of his long lean face, might have tongued his quid a time or two, before saying, "Pore ole soul. I reckon that woman ain’t never figgered out the kind of world the Almighty made." Three Finger McNees would have been laconic: "Why don’t she go home?"

The mountain men rumbled with astonishment on learning that Kate sat in moonlight reading aloud from the Bible to her children. It was a very old Bible that had belonged to her mother’s mother; and because many verses had been emphasized in the margin with blue ink she had only to turn the pages and look for the signals. When she came to one that had been marked she would read it, her lips moving but making no sound; and if she thought it was something her smiling and nodding darlings would like she would read it to them: " 'I the Lord have called thee in righteousness, and will hold thine hand, and will keep thee, and give thee for a covenant of the people; to open the blind eyes, to bring out the prisoners from the prison, and them that sit in darkness out of the prison house.'

After reading such verses she would look at her children and smile and nod; and like long-stemmed flowers they would nod and smile. She did not have a cultivated voice but it was clear and strong; ever since they were old enough to understand she had read to her children from the holy book. Sometimes she closed the book and let it open where it would. It might be on a psalm: " 'O my God, I trust in thee, let not mine enemies triumph over me.’ " Smiling at them, she would say, "Your father left us some things last night. He is very busy these days; he wants us to wait here, for he will come to us sometime."

In the dark of her senses she knew her husband was not dead, for if he were, he would be an angel here, with his children. She wondered why he rode up and down the river. She would have said he was not trapping, for he had never trapped; he had been a farmer for a while, then a small merchant. Why he never hitched his team to a wagon she did not know; he was doing his work in ways he thought best, and when all things were fulfilled he would come to them.

She knew that, being angels, her children could give no answers, except the heavenly smiles and the gentle assents. In time of full moon, when she could see them most clearly, Kate did not go to bed until the moon was down. For how could she have left them there, kneeling in the sage and smiling at her? Sometimes the moon did not go down till morning, or did not go down at all but just faded away into the day sky; only after her children had slipped back to their blue home did she rise from the buffalo robe that had been left by her husband. If after her children had left her her loneliness was too bitter to bear she would not enter the shack but would stand by it. In such moments she came closest to a realization of where she was—no, not of where she was, for since leaving the Big Blue she had never known where she was; but of her aloneness and helplessness and enemies. She might then step over to look almost curiously at the spots where her children had knelt; it was then that she came closest to an impulse to search the earth for footprints.

But in a few moments it all passed. She would then become conscious of the book in her hands, and there would come to her, infinitely sweet and tender, memory of her three angels, who would be there again after the moon had risen. During the long empty days she had this to look forward to and it sustained her. Her deeper emotions, of which she had no awareness, and which seldom looked out of her features, she revealed in curious ways. Instead of making her bed back in the cabin, away from the door, she made it right by the door, so that she had to step over it; so that, lying in it, she could put a hand out of the ugly little prison and touch the big world. Against a wall at either end of the bed were piled her food and utensils; and there her rifle stood. When she was not carrying water to her plants she might sit on the bed, with needle and skins, and sew on leather jackets or skirts or moccasins. She would look over innumerable times to see if her children had come, or up at the sky to see if the moon was there. Sometimes when coming from the river she would think she heard a son calling, and she would run like a wild woman, trembling in every nerve. Coming to the yard and finding that her children were not there, she would be a tragic picture of loss and hopelessness, too stricken to look or listen.

Or if when reading to her darlings and answering their smiling angel-faces she heard the sound of an enemy—the snarling challenge of a wolf almost at her door or the shriek of a descending hawk—she was instantly transformed into a tigress; and seizing the axe, she would rush blind and screaming against the challenge. No beast was ever to withstand her charge.

It was this sort of thing that spread in legends. In a moonlit night, a year or two after the massacre, Windy Bill was passing by when he heard wild screams and on a hill against the sky saw a woman rushing round and round, the blade of her axe flashing. "I took plum off fer the tall timber," he said. "My hair it stood up like buffler grass and my blood was like the Yallerstun bilins John Colter saw." He improved, or in any case embellished, his tale with each retelling, until what he saw was la witch riding a broom in the sky and shrieking into the winds. Other men were to see Kate, when passing her way, and to tell tales about her, and the legend of her would grow in an area of more than a million square miles; but while it was still in its innocent beginnings, other legends, to be still more awesome and incredible, were being born, and one of them would enfold the huge figure of Samson John Minard.

It had its origin in his decision to take a wife.

5

THE FREE TRAPPERS were the most rugged and uncompromising individualists on earth. Only now and then did one think of an Indian mate as a wife, even after accepting her in the marriage ceremony of the red people; but Sam Minard had a sentimental attachment to his mother and to an older sister, and under his bluff and reticent surface were emotional channels in which feeling ran heavy and warm. His closest friends were never to know it. Hank Cady, Windy Bill, Jim Bridger, George Meek, Mick Boone, and others who knew him and were to know him best thought that a red woman was for Sam what she was for them, a member of a subhuman species that a man might wish one day to take to bed and the next day to tomahawk. Dadburn his possibles, one of them said; there warn’t no human critters except the white. The red ones and the black ones were what the Almighty had in leftovers after making the twelve tribes. Most of the white trappers thought nothing at all of the redman’s habit of kicking his old wife-squaws into the hills, to die of disease, starvation, old age, or to fall prey to the wolves.

Sam had a different view of it but he kept it to himself. Last spring he had seen an Indian lass who took his fancy. Since then he had dreamed about her, and using some thrush and meadow-lark phrases, had tried to compose lyrics to her. The logical part of his mind saw objections to taking a wife. He wondered, for instance, if the physical mating of a girl weighing a hundred and fifteen pounds with a man of his size was the kind an all-wise Father would smile on. Sam was sensitive about his size. His mother had told him that at birth he was so huge that his father, after one appalled look, had said he guessed they’d have to name him Samson. It was no fun being so big and it was a lot of bother. A second objection was her age; she was only about fourteen or fifteen (he thought), and though he was only twenty-seven he seemed to himself middle-aged compared to her. A third objection, he had decided after much thought, was really no objection at all: he suspected that she was not all Indian; the Lewis and Clark men had left white blood running in Indian nations all the way from St. Louis to the ocean.

Sam had been surprised to learn the origin of the Flathead name. Formerly (they had now abandoned the custom) they had hollowed out a chunk of cedar or cottonwood and spent hours dressing it, carving it, and making it buckskin fancy. This cradle or pig’s trough or anoe or canim they then lined with cattail down, the fluffy inner bark of old cedar trees, the wool of bighorn sheep; and when it was nicely lined and looked cozy they slapped it on the poor baby’s skull almost the instant it was born, and swaddled its head over with tanned deerskins as soft as the underflank of a baby antelope. Laid out on its back, its black eyes staring at the red wise men, the babe then had a feather or wool shawl drawn across its forehead and around. Finally a long flat board, attached at one end to the canim, was forced down on the shawl and the forehead and bound with leather strings, thus putting considerable pressure on the soft bone of the foreskull. The luckless babe was then so securely wrapped and bound that it was unable to move a hand or foot, and did well to wiggle a linger and blink its eyes. In such horrible confinement it remained a year or more, except in those moments when it was unbound and washed clean of its filth and bounced up and down for exercise. The steady pressure on the skull caused the head to expand and flatten, like a big toad stepped on by a grizzly paw, so that the aspect of the upper face became abnormally broad and the skull flat.

The girl of whom Sam was enamored had not had her skull flattened; she was, he thought, the loveliest human female he had ever seen; she was lovelier, even, than the gorgeous alpine lilies, or the columbine with its five white petals in a cup framed by five deep-blue sepals. She was a golden brown all over, but for her hair, eyes, and lips. Her hair and eyes were raven-black, and her inner lips were of a luscious dark pink that he wanted to bite. Whether she was full-grown he had not been able to tell, but she had already had, at her early age, the womanly form, with the kind of full breasts, firm and sitting high; that a man saw on Indian girls only now and then. The quality of her that had most entranced him was what he might have called, had he found words for it, a vivacious surfacing of her emotions, like tossing water spindrift flashing with the jewels of sunlight; and she had a way of looking at a man as though she wished to tease and excite and bewitch him. It had been mighty good to look at and he was now on his way over to buy her.

That would be the most unpleasant part. An Indian chief, whether Flathead, Crow or Sioux, or even the lowly Digger, began to itch all over with avarice the moment he sensed that a paleface coveted one of his females. If it were not for the redman’s fantastic love of trinkets and trifles which the Whiteman could buy for a song, the cost of a red wife would have been too much for the trapper’s purse. Sam had learned that those who said the redman was not a canny bargainer simply did not know him. This girl’s father, Chief Tall Mountain, had put her up for sale outside her tribe; this proclaimed to every person who knew Indian ways that the greedy rascal thought she was worth a hundred times an ordinary red lilly. The chief would expect handsome gifts for himself. Then there would be her mother, stepmothers, aunts and uncles and brothers and sisters, step-aunts and step-uncles, step-brothers and step-sisters, and so many cousins that she would appear to be related to every person in the tribe, all hoping for nothing less than a fast horse, a Hawken rifle with a hundred rounds, a brace of Colts, a Bowie, a barrel of rum, a keg of sugar and another of Hour, a bushel of beads, and a small mountain of tobacco. The dickering would take weeks if you could put up with it. You’d have to let it drag out for several days, for the reason that a part of the redman’s joy in life came from prolonging anticipation of what he knew he could never get.