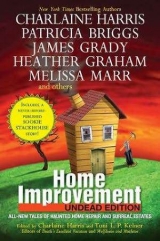

Текст книги "Home Improvement: Undead Edition"

Автор книги: Сьюзан Маклеод

Соавторы: Seanan McGuire,Rochelle Krich,Toni Kelner,Simon R. Green,E. e. Knight,S. J. Rozan,Charlaine Harris,Melissa Marr,Stacia Kane

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“I know what you mean,” Johnny Jay said diffidently. “I won’t go back to London. I just won’t. Ever since I won that damned talent contest, the television people and the tabloids have been making my life a misery. I never wanted to be a national icon; I just wanted to sing, and make people happy. The tabloids have been doorstopping all my family and friends, and anyone who ever spoke to me, looking for interestingstories; and when they don’t find any, they just make some up! I’ve never even been to Spearmint Rhino!”

“I am not leaving!” said Leanan-Sidhe. “I have claimed Sanctuary, and I know my rights! I demand that you protect me from this unwelcome outside interference!”

Peter looked at Jubilee. “The rules of the House say we have to give Guests Sanctuary. No one ever said we had to like them.”

“We can still give them a good slap,” said Jubilee.

“Can I watch?” said Johnny Jay, brightening up a little.

“We have to do something,” said Peter. “If the nature of the House is compromised, if the two worlds can no longer be kept separate . . . Could that actually happen, princess?”

“I don’t think the matter has ever arisen before,” said Jubilee, frowning thoughtfully. “The House exists in a state of spiritual grace, of perfect balance between the two worlds of being. Shift that balance too far either way, and this House could cease to function. A new House would have to be created somewhere else, with new management. We would not be considered. We would have failed our duty. After all these centuries, we would be the first to fail the House . . .”

“It hasn’t come to that yet, princess,” said Peter, laying one hand comfortingly over hers. “Can the House really be threatened so easily? I thought the House was created and protected by Higher Powers.”

“We’re supposed to solve our own problems,” said Jubilee. “That’s the job.”

“Cuthbert might not know what he’s doing,” said Lee, “but you can bet that bloody Elf does. He must understand the implications of what he’s saying.”

“Of course he does!” said Jubilee. “He knows exactly what he’s doing. Our usual avoidance fields didn’t just happen to fail, revealing us to the normal world, at exactly the same time the Unseeli Court decides to take an interest in us. This was planned. I think somebody targeted us, set this all in motion for a reason.”

“To destroy the House?” said Lee.

“Who would want to do that?” said Johnny Jay.

“Or . . . are they doing this to get at someone who thought they were safe, inside the House?” Lee scowled, and something of her darker persona was briefly present in the kitchen with them. They all shuddered briefly. Lee politely pretended not to notice. “I thought anyone who claimed Sanctuary here was entitled to full privacy and protection? If any of those demanding little poets have followed me here to make trouble . . .”

“Your safety in all things is guaranteed, for as long as you care to stay here,” Jubilee said coldly. “It isn’t always about you, you know. I think . . . this is all about me, and Peter. It’s all about us.”

“Your family never was that keen on our marriage, princess,” Peter said carefully.

“It wasn’t their place to say anything,” said Jubilee. “It’s the tradition, that the House’s management should be a married couple, one from each world. I was happy to marry you, and happy to come here; they should have been happy for me.”

“I was never happier than when you joined your life to mine,” said Peter. “You’re everything I ever wanted. The House was just a wonderful bonus. But . . . if our marriage is threatening the House . . . I’m here because I wanted to be part of something greater, something important. I won’t let that be threatened because of me. We can’t let the House be destroyed because of us, princess. Not when it’s in our power to save it.”

“It’s my family,” Jubilee said grimly. “Has to be. My bloody family. They’d be perfectly ready to see this House destroyed, just to have me back where they think I belong. Because they can’t bear to believe that they might be wrong about something. Maybe . . . If I were to go back, they might call this off . . . But no. No . . . I could leave this House to protect it, but I couldn’t leave you, Peter. My love.”

“And they’d never accept me,” said Peter. “You know that. I’d have to agree to leave you before they’d take you back.”

“Could you do that?” said Jubilee.

“The House is bigger than either of us,” said Peter. “We’ve always known that, princess. I could not love thee half so much . . .”

“. . . Loved I not honor more,” said Jubilee. “We both love this House: what it represents, and the freedoms it preserves.”

“That’s why we got the job,” said Peter. “Because we’d do anything to protect this place. And now that’s being turned against us.”

“I could leave,” Lee said abruptly. “If I thought it would help. If only because you two clearly serve a Higher Power than me.”

“Same here,” said Johnny Jay.

“No!” Peter said flatly. “Either the House is Sanctuary for everyone, or it’s Sanctuary for no one. You mustn’t go, or everything we might do would be for nothing.”

“And we can’t go either!” Jubilee slammed her hands down flat on the tabletop, her eyes alight with sudden understanding. “Because that’s what they want! They’re depending on our sense of duty and responsibility to outweigh our love for each other. That we’d be ready to break up to preserve the House! I’m damned if I’ll let my arrogant bloody family win! There has to be a way . . .”

“It’s not as though we’re defenseless,” said Lee, her bloodred mouth stretching wide, revealing far too many teeth for one mouth. “Let us lure them in here, and I will teach them all the horror that lurks in the dark.”

“Do you sing, oh muse of psychologically challenged poets?” said Johnny. “Because I’ll wager good money that between us we could whip up a duet that would rattle the bones and trouble the soul of everyone who heard it, whatever world they came from.”

“We will chase them, we will chase them, we will eat them up with spoons!” chanted the small furry things in the doorway, while the ball bounced excitedly up and down between them.

“I could throw things at people,” Walter said diffidently from the fridge. “If they got close enough.”

There was a low steady rumbling, from up in the attic, as Grandfather Grendel stirred. When he spoke, his words hammered on the air like storm clouds slamming together.

“Let all the worlds tremble, if I must come forth again. There have been many powers worse than Elves, and I have slaughtered and feasted on them all, in my time.”

“No!” Jubilee said sharply. “This House was created by the Greatest of Powers to put an end to conflicts, to give hope and comfort to those who wanted only peace. If we defend the House with violence, we betray everything it stands for. There has to be another way.”

“There is.” Peter leaned forward across the table, taking both of Jubilee’s hands in his. “The House exists . . . because it is necessary. It was brought into being, and is protected by, Powers far greater than your damned family, princess. Even your people wouldn’t dare upset those Powers—so call their bluff! Tell them that if this House’s function is destroyed because of them, we’ll make sure everyone knows it’s all their fault! Tell them; it’s all about rendering unto Caesar. Let both sides perform whatever home improvements they feel necessary . . . as long as they don’t interfere with each other, or the running of the House! Or else! Your family might have raised arrogance to an art form, but even they’re not dumb enough to anger the Powers That Be.”

“Peter, my love, you’re brilliant!” said Jubilee. “I think this is why I love you most. Because you save me from my family.”

“Any time, princess,” said Peter.

THE NEXT DAY,bright and early, but not quite as early as the day before, there was a very polite knocking at the House’s front door. When Peter went to open it, he found Mister Cuthbert standing there, looking very grim. He nodded stiffly to Peter—or at the very least, in Peter’s direction.

“It seems . . . there may have been a misunderstanding,” he said, reluctantly. “It has been decided in Council that this residence is exempt from all health and safety regulations and obligatory improvements. Because it is a Listed and Protected building. No changes can be made, without express permission from on high.” Mister Cuthbert glared impotently at Peter. “I should have known the likes of you would have friends in high places!”

“Oh yes,” said Peter. “Really. You have no idea.”

And he shut the door politely but very firmly in Mister Cuthbert’s face.

Meanwhile, at the back door, Jubilee was speaking with the Elven Prince Airgedlamh, of the Unseeli Court.

“So it was you,” she said.

“Yes,” said the Elven Prince. “All things have been put right; no improvements will be necessary. The Unseeli Court has withdrawn its interest in this place. The House shall endure as it always has; and so shall you, and so shall we.”

“Go back to the family,” said Jubilee. “Tell them I’m happy here.”

“Of course. But there are those of us who do miss you at Court,” said the Elven Prince. “Good-bye, princess.”

In Brightest Day

TONI L. P. KELNER

I’d thought I’d have most of the day free for Internet surfing—a mixed blessing resulting from not having any clients in the offing—but the phone rang just as I was finishing the weekly lolcat roundup. I let it ring twice before answering, hoping that would demonstrate promptness without the betraying stench of desperation.

“Rebound Resurrections,” I said in my best business voice. “How can I help you?”

“Dodie? It’s Shelia Hopkins. Gottfried is dead.”

“Well, yeah.” He’d been dead for a couple of weeks.

“I mean he’s dead again.”

I could have corrected her once more—technically Gottfried was dead still, not dead again—but I figured it would go faster if I let her explain. The problem was that Gottfried was no longer moving or responding. That might be normal behavior for most dead people, but no matter what some of my fellow houngans might think, I’m pretty good at what I do.

I raise the dead for a living.

* * *

THIS PARTICULAR JOBhad started out well enough. The work crew had nearly unearthed the coffin by the time I got to the cemetery the day before, so I just said hello-how’s-it-going and let them keep digging. A foursome—two women and two men—showed up a few minutes later, and I voted the distinguished woman in a navy skirt suit and sensible heels most likely to be my client.

“Mrs. Hopkins?” I asked. “I’m Dodie Kilburn.”

I know she was surprised—she and I had handled all the advance work via phone and e-mail—but she was too well bred to comment on the fact that I don’t look much like a typical houngan.

As soon as I got my ring and license from the Order of Damballah—the houngan version of a professional organization—I’d dumped the wannabe voudou queen look: hair dyed jet-black, loose cotton skirts, low-cut peasant blouses, and a tan-in-a-can. That meant I was back to my natural strawberry-blond hair and freckles and was wearing jeans and a turtleneck sweater.

Mrs. Hopkins introduced the other three, and they all shook my hand somewhat reluctantly, but I didn’t take it personally. A lot of people freak when they meet a houngan, and it’s even worse when said houngan is about to raise a revenant. So it was no surprise that they stuck with weather-related chitchat while we waited. For the record, it was unseasonably cool for fall in Atlanta.

Once the workers got the coffin out of the ground and next to the open grave, they had me sign their paperwork and took off. Unlike Mrs. Hopkins and company, they weren’t bothered about what I was about to do—they just wanted to get home in time to catch the Falcons game. They’d be back the next day to take the coffin to a storage shed and temporarily fill in the grave.

Once they were gone I said, “I’m ready to get started.”

“Already?” asked Elizabeth Lautner, the other woman in the group. When Mrs. Hopkins had said she was the dead man’s assistant, Elizabeth corrected her—she’d been his associate. Elizabeth’s dark brown hair was in a short, asymmetric cut, and she was wearing more mascara than I use in a year. “I thought that you had to wait until midnight to raise a zombie.”

“Number one, we don’t like to call them zombies. Revenantis the PC word. And honestly, it doesn’t matter what time of day it is. We only work nights because the cemetery managers don’t want us working while they’re trying to have funerals. Go figure. By the time a cemetery shuts down for the day and the crew gets the coffin out of the ground, it’s usually close to midnight anyway. We just lucked out tonight.” Not only was there the football game, but the man hadn’t been buried very long, so the ground was fairly soft.

One of the men nervously asked, “Do you open the coffin now?” He was Welton Von Doesburg, and I think he’d picked his suit to live up to the name. He’d identified himself as Von Doesburg Realty, giving the impression that anyone in the known universe would know what that meant.

“I won’t open it until I’ve brought Mr. Gottfried back,” I said.

“Just Gottfried,” Elizabeth said.

“Right, like Cher or Gallagher.” I didn’t get so much as a snicker in response. “Anyway, the coffin doesn’t affect the ritual.”

“I read about that,” said C. W. Ford, a man with a solid build and worn jeans. “Loas can go right through a coffin.” Mrs. Hopkins had said he was Gottfried’s construction chief.

I said, “I don’t really have much to do with the loas. I’m more of a force-of-will kind of gal. You know, like the Green Lantern—I’ve got the power ring and everything.” I held up my right hand with the golden signet ring. The engraving was of an ornate cross, the vévé of Baron LaCroix, the Order’s mascot. “ ‘In brightest day, in blackest night, no evil shall escape my sight.’ ”

I waited a second to see if anybody would finish the Green Lantern oath, but all I got were blank stares. “Green Lantern from the comic book?” I prompted. “Or the Ryan Reynolds movie?”

“We should let you get to work,” Mrs. Hopkins said with a hint of impatience.

“You bet. If you folks wouldn’t mind stepping back a bit . . .”

They did so, and I got my carton of Morton’s salt out of my satchel and started walking around the coffin, pouring it as I went. “Be sure not to break this line.”

“What happens if we do?” Von Doesburg asked.

“Nothing dire. I just won’t be able to raise Gottfried. Now I’ll need the sacrifice.”

“I’ve got it,” Mrs. Hopkins said, reaching into a leather briefcase.

“I read that houngans used to cut the throat of a rooster,” C.W. said.

“They do still do in some parts of the world, but it doesn’t work here. If sacrificing a chicken meant that you were going to go hungry for a week, that would be meaningful. But giving up a chicken isn’t a big deal for you or me. We need a real sacrifice. It could be anything valuable, even just sentimental value, but it’s handier to use something with a known price tag.” If for no other reason than because it made it easier for the Order to set standard rates.

“Here you go,” Mrs. Hopkins said, handing me a velvet pouch. I poured a quarter-carat diamond onto my hand, and even in the dim evening light, I could see the sparkle. I slipped it back into the pouch and then put it on top of the coffin.

Von Doesburg said, “What’s to keep you—I mean, an unscrupulous houngan from pocketing the diamond when nobody is looking and then pretending that the loas took it?”

I wanted to tell him that if I’d pocketed a diamond every time I raised a body, I’d have a better car than my six-year-old Toyota, but he wasn’t the first one to ask, so I restrained myself. “Tell you what, why don’t you come over here next to the coffin? Just be sure to step over the salt line.”

His eyes got wide, and I think he’d have made an excuse if C.W. hadn’t snickered. That was when he stomped over. “Now what?”

“Hold out your hand.”

He obeyed.

I reopened the pouch and let the diamond fall onto his palm. “Now make a fist and hold it over the coffin while I do the ritual. If that rock is still there when I’m done, you can keep it.”

Papa Philippe, my sponsor at the Order, wouldn’t have approved of my letting a civilian get involved, but I figured it was the best way to prove my point.

Once Von Doesburg was in place, I began the ritual, which really isn’t that much to see unless you throw in the voudou special effects and dance numbers some of my fellow houngans favor. First I knocked on the coffin three times. With some jobs, I add a knock-knock joke at that point, but this didn’t seem like the right crowd. Then I gathered my will and reached into the body of the man in the coffin, though to the onlookers it probably just looked like I had a real bad headache. That was pretty much it.

When I felt Gottfried stirring, I started unscrewing the fasteners holding the lid shut.

Von Doesburg stepped back in such a hurry that he broke the salt line, but I didn’t need it anymore anyway. It would have been nice if he’d helped me get the lid open, but I managed on my own and looked inside. The mortician had done a good job with Gottfried. He looked fairly natural.

The revenant blinked up at me, and when I held my hand out toward him, he let me help him out of the coffin. His skin was cold to the touch, of course, but I’m used to that. Fortunately he was wearing a real suit, not one of those backless things. A dead man’s ass isn’t particularly appealing to me.

“Gottfried?” I said.

“Yes, I’m Gottfried,” he said, showing the usual amount of new revenant confusion.

“Do you know where you are?”

“I’m . . .” He looked around the cemetery, then at the coffin he’d climbed out of. “Am I dead?”

“Yes, you are.” Back when houngans first went public, it had been tricky to convince a fresh revenant that he was actually dead, but I’d never resurrected anybody who hadn’t already known it could happen to them. That made it easier for everybody concerned. “I brought you back to finish your last job. Do you remember what that is?”

It’s important for a revenant to know why he’s back in this world. Houngans, at least licensed ones, don’t just bring people back for fun. First off, we need the permission of the next of kin. Second, there has to be a compelling reason for us to take on a job. It was okay to bring back Grandma to tell the family where she’d hidden the Apple stock certificates, or Dr. Bigshot to finish a research project, but not to bring back Marilyn Monroe for a reality show. Third, the revenant has to be willing to take on that task. Once Gottfried’s was done, he’d have to go back to the grave.

It’s like Papa Philippe says: we just raise the dead, we can’t bring ’em back to life.

Gottfried hesitated just long enough to worry me, but then said, “The house. I was renovating a house. I’ve never done a house before. It’s special. It’s going to be my famous house, like Frank Lloyd Wright had Fallingwater.”

It wasn’t the explanation I’d been expecting. According to Mrs. Hopkins, the house was special because after Gottfried fixed it up, it was going to be sold to raise money for the Stickler Syndrome Research Foundation, of which she was the chairman. But as long as it was important to him, the ritual would work.

“Are you willing to stay long enough to finish the house? Because if you’re not, I’ll lay you back to rest right now.” I could tell Mrs. Hopkins didn’t like it when I said that, but I’d explained to her that no houngan could make a revenant walk the earth if he didn’t want to.

So we both relaxed when Gottfried said, “I want to finish the house.”

“Awesome. Now do you remember these people?”

That was another test: to be sure Gottfried had come back with enough of his faculties to finish his work.

Gottfried focused on them, his reactions getting closer to normal every second. “Yes, of course. Hello, Shelia.”

“I’m glad to see you, Gottfried,” Mrs. Hopkins said, but she didn’t come any closer. No surprise there. No matter how determined my clients are, they still tend to freak when they see a dead man walking.

Gottfried went on. “C.W. Elizabeth. Von Doesburg.” He looked at me. “I don’t know you, do I?”

“No, I haven’t had the pleasure. I’m Dodie Kilburn. I’m going to help you get that house finished.”

“Good. I want to finish the house.”

Revenants aren’t known for their conversational skills—once one has focused on a task, that’s all he’s interested in. Gottfried must have had a strong focus even while living to have already fixated on his.

I said, “Gottfried, I’m going to take you to a special hotel for the night.”

“Because I can’t go home anymore.”

“That’s right.” We started down the path to the cemetery exit, and I said, “Mrs. Hopkins, I’ll bring Gottfried to the work site tomorrow.”

“That’ll be fine.”

“And Mr. Von Doesburg, you can open your hand now.”

He did so, then stared at his empty palm. The diamond was long gone.

THERE WAS NOneed for me to stick around once I’d checked Gottfried in at the Order’s Revenant House. It was the job of the apprentice houngans working there to explain what he’d need to know about being a revenant: stuff like him not having to eat or go to the bathroom, though drinking water would help him speak; how his sense of touch wouldn’t come back completely, which meant that he wouldn’t feel much pain but would have to be careful to keep from damaging himself, since he couldn’t heal anymore. Of course, he’d likely seen a revenant at some point, so he might remember how it worked, but it was different when you were the dead one.

I was walking back to the parking lot when I saw a shadowy figure waiting for me. I stopped, and a man dressed in a shabby top hat and a tailcoat worn over a bare chest sauntered toward me. He was carrying a cane with a silver skull for a knob, and there was a chicken foot sticking out of his hatband. His black skin gleamed as if it had been oiled, which it probably had been.

“Dude,” I said.

He didn’t respond.

I sighed, then said, “I see you, Papa Philippe.”

“Dodie Kilburn,” he said in a husky voice, “I hear you raised a man for no good reason.”

“Says who?”

“The loa be telling me.”

“Don’t the loa have better things to do?”

“They do,” Philippe said, dropping out of his voudou patois, “but Margery doesn’t.”

“I should have known.” Margery, the woman who ran the office of the Order, knew the business of every houngan in the Atlanta area. “Then she should also have told you that I had an excellent reason to bring Gottfried back.”

“Actually, I should have heard it from you, what with being your sponsor.”

“Since when do I have to get approval for a job?”

“Since you took one that three other houngans turned down.”

I had wondered about that—it wasn’t like I had clients busting down my door. Most newer houngans get referrals from established ones, but most older houngans think I’m a flake. “I don’t know what their problem was, but I did my homework. The next of kin signed off on it, and the job fits Order guidelines.”

“Bringing back a world-famous architect to fix a house?”

“It’s a special house, like one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses.”

He didn’t look impressed.

“And it’s for charity.”

No response.

“Am I in trouble with the Council?”

“There’s been some talk, which could have been avoided if I’d known ahead of time.”

“I’m sorry—the client was in a hurry, and—”

“And you haven’t had much work this month.”

“No, not so much.” I hadn’t had much the month before, either. If things didn’t improve, I was going to have to either go work with my father’s insurance agency or go work for another houngan, which would probably mean doing the whole voudou queen thing, including trying to make Dodie sound appropriately exotic. If I’d had any dealings with the loa, I’d have sacrificed my autographed photo of the cast of The Big Bang Theoryto get them to throw more work my way.

Philippe said, “Just give me the details.”

I told him what Mrs. Hopkins had told me, that a supporter had left a dilapidated mansion to the Stickler Syndrome Research Foundation in his will, and how she’d gotten the idea of reimagining the place in order to sell it for mucho bucks. Somebody knew somebody who knew somebody who knew Gottfried the architect and talked him into taking on the job pro bono. Unfortunately, midway through the project, Gottfried fell down a flight of stairs at his condo and broke his neck, which left the project in limbo.

“Couldn’t somebody else finish the job from his plans?” Philippe asked.

“Gottfried wasn’t big on planning. They had some rough sketches, but Gottfried is famous for adding things as he goes, and without all those special touches, they won’t be able to get nearly as much money. Not to mention the fact that Gottfried started the crew doing some things without telling them what he was aiming for, so there’s all kinds of work half-finished. They really do need him.”

“And he’s willing to do the job? You asked him?”

“Duh!”

“Okay, I think I can spin it the right way. But if you get another job like this one, please run it past me first.”

“You bet.”

“ ’Cause Papa Philippe think you make master houngan someday if even it kill you—if it do, he be bringing you back hisself.”

THE APPRENTICES HADGottfried all ready to go when I got back to Revenant House the next morning, and they had found him a pair of khakis and a polo shirt to wear instead of his burying suit. Though he told me good morning when he got in, he didn’t say anything else for most of the drive. I took that to mean that he was ready to hunker down and work.

The house he was working on was part of a gated community in Dunwoody, one of the pricier Atlanta suburbs, and the security guard didn’t look impressed by my beat-up car. Then he saw Gottfried and did a double take before letting me drive into the Emerald Lake development.

The town houses and lawns looked nauseatingly perfect, and Gottfried must have agreed, because he blurted out, “Cookie-cutter crap.” I saw several signs proudly proclaiming that Emerald Lake was a Von Doesburg development, which explained why the man had been at the cemetery the night before.

The mansion being renovated was at the end of a road, right on the lake, and obviously predated the cookie-cutter crap. It had three stories, wide white columns, a balcony on the second floor, and a veranda that stretched all across the front of the building. There were tarps and piles of supplies everywhere and a Dumpster in the middle of the front yard, but I could see it was going to be a showplace. No wonder Gottfried had been willing to come back to finish.

As soon as I parked, Gottfried got out and started walking toward a trailer parked on the edge of the lot, so I followed along. A sign on the door said CONSTRUCTION OFFICE, and when Gottfried opened it, we saw the four people from the previous night plus another guy.

“Good morning, Gottfried,” Mrs. Hopkins said, but Gottfried went right past her to go to the desk and start flipping through papers.

“Well!” said the newcomer, a scrawny man with his nose hiked up in the air.

“Dodie,” Mrs. Hopkins said, “this is Theo Scarpa, the president of the Emerald Lake Homeowners’ Association.”

I said pleased-to-meet-you.

“Mr. Scarpa has some questions about . . .” She glanced at Gottfried. “About your work.”

Scarpa sniffed, and at first I thought it was a comment on me, but then realized he was checking to see if Gottfried stank of rotting flesh.

I said, “No, he doesn’t smell. In fact, revenants smell better than most living people.”

“I see,” he said, as if suspecting a hidden insult. “Sorry, but this is my first experience with this kind of thing. Can you tell me how you expect him to be able to finish a renovation this complex? It’s my understanding that a revenant has limited mental capacity.”

“It’s not that his capacity is limited—it’s just very focused. Gottfried is just as capable of finishing this house as he was when he was alive. The difference is that he no longer has any interest in anything other than this task.”

“But he’s got to modify his plans to fit into our development,” he said, waving a handful of papers at me. “How can he do that?”

“This house predates the development,” Gottfried’s assistant, Elizabeth, said. “You should be modifying those trashy houses to match his work.”

The two of them started in on each other, ignoring Von Doesburg when he tried to calm them down. I said, “Mrs. Hopkins, if you want my advice, I’d say to let Gottfried get to work.”

“That’s an excellent idea,” she said. “C.W., why don’t you take him out to the house?”

The construction chief nodded and said, “Come on, boss, and I’ll show you what we’ve done while you were gone.”

“Gottfried, I’ll be back this evening to take you back to Revenant House,” I said, but he didn’t even pause. As I’d told Scarpa, his attention was all on the house. I checked with Mrs. Hopkins to see what time I should pick him up, and left her to handle the bickering.

It was at about three thirty that afternoon when I got that panicked call about Gottfried being dead. Again.

FOR ONCE Iwas glad I didn’t have any other jobs going so I could drive over there right away. A bunch of men wearing tool belts were standing around, and when I got out of my car, Elizabeth came running over to nearly drag me inside the house.

Just past the front door was a gorgeous set of stairs, the kind made for sweeping down in a ball gown. The image was spoiled by the sight of Gottfried’s body at the bottom. And it was a body, not a revenant—he didn’t even look a little bit alive anymore, and the smell of formaldehyde was strong. Mrs. Hopkins and C.W. were looking down at him.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Your damned spell wore off,” Elizabeth snapped, “and he fell down the stairs.”

“Wait. He died before falling? You saw that?”

“No, I didn’t see it—I was in the trailer—but what else could have happened?”

I pushed past her and went up the stairs. The floor up there was covered with a sheet of sturdy paper that must have been taped down to protect the wood from the workers, and the tape at the very edge had peeled off, leaving a fat curl of paper.

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 04] - The Cornish Pixie Affair автора Peter Leslie](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-04-the-cornish-pixie-affair-199172.jpg)