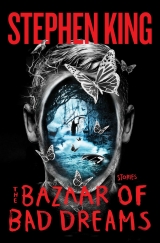

Текст книги "The Bazaar of Bad Dreams"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

No, Ardelle, the bike and the pool ain’t particularly important to the story, but if you want it, you’ll have to take it my way. And I find it interestin. There was even a home theater set up in the basement. Jeezly Crow, I felt like movin in.

The fireworks was in his garage under a tarp, all stacked up in wooden crates, and there was some pretty awesome stuff. ‘If you get caught with it,’ he said, ‘you never heard of Howard Gamache. Isn’t that right?’

I said it was, and because he seemed like an honest enough fella who wouldn’t screw me – at least not too bad – I asked him what five hundred dollars would buy. I ended up gettin mostly cakes, which are blocks of rockets with a single fuse. You light it, and up they go by the dozen. There was three cakes called Pyro Monkey, another two called Declaration of Independence, one called Psycho-Delick that shoots off big bursts of light that look like flowers, and one that was extra-special. I’ll get to that.

‘You think this stuff will shut down those dagos?’ I asked him.

‘You bet,’ Howard said. ‘Only as someone who prefers to be called a Native American rather than a redskin or a Tomahawk Tom, I don’t care much for such pejorative terms as dagos, bog-trotters, camel jockeys, and beaners. They are Americans, even as you and I, and there’s no need to denigrate them.’

‘I hear you,’ I said, ‘and I’ll take it to heart, but those Massimos still piss me off, and if that offends you, it’s a case of tough titty said the kitty.’

‘Understood, and I can fully identify with your emotional condition. But let me give you some advice, paleface: keep-um to speed limit going home. You don’t want to get caught with that shit in your trunk.’

When Ma saw what I’d bought, she shook her fists over her head and then poured us a couple of Dirty Hubcaps to celebrate. ‘When they experience these, they’re gonna shit nickels!’ she said. ‘Maybe even silver dollars! See if they don’t!’

Only it didn’t turn out that way. I guess you know that, don’t you?

Come the Fourth of July last year, Abenaki Lake was loaded to the gunwales. Word had got around, you see, that it was the McCausland Yankees against the Massimo Dagos for the fireworks blue ribbon. Must have been six hundred people on our side of the lake. Not so many over on their side, but there was a bunch, all right, more than ever before. Every Massimo east of the Mississippi must have shown up for the oh-fourteen showdown. We didn’t bother with piddling stuff like firecrackers and cherry bombs that time, just waited for deep dusk so we could shoot the big stuff. Ma n me had boxes with Chinese characters stacked on our dock, but so did they. The east shorefront was lined with little Massimos waving sparklers; looked like stars that had fallen to earth, they did. I sometimes think sparklers are enough, and this morning I sure wish we’d stuck to em.

Paul Massimo waved to us and we waved back. The idiot with the trumpet blew a long blast: Waaaaaah! Paul pointed to me, as if to say you first, monsewer, so I shot off a Pyro Monkey. It lit up the sky and everyone went aahhhh. Then one of Massimo’s sons lit off something similar, except it was brighter and lasted a little longer. The crowd went ooooh, and off went the fuckin trumpet.

‘Never mind the Funky Monkeys, or whatever they are,’ Ma said. ‘Give em the Declaration of Independence. That’ll show em.’

I did, and it was some gorgeous, but those goddam Massimos topped that one too. They topped everything we shot off, and every time theirs went brighter n louder, that asshole blew his trumpet. It pissed off Ma n me no end; hell, it was enough to piss off the pope. The crowd got one hell of a fireworks show that night, probably as good as the one they have in Portland, and I’m sure they went home happy, but there was no joy on the dock of the Mosquito Bowl, I can tell you that. Ma usually gets happy when she’s in the bag, but she wasn’t that night. It was full dark by then, all the stars out, and a haze of gunpowder driftin across the lake. We was down to our last and biggest item.

‘Shoot it,’ Ma said, ‘and see if they can beat it. Might as well. But if he blows that friggin trumpet one more time, my head’s gonna explode right off my shoulders.’

Our last one – the extra-special – was called the Ghost of Fury, and Howard Gamache swore by it. ‘A beautiful thing,’ he told me, ‘and totally illegal. Stand back after you light it, Mr McCausland, because it goes a gusher.’

Goddam fuse was thick as your wrist. I lit it and stood back. For a few seconds after it burned down there was nothin, and I thought it was a dud.

‘Well, don’t that just impregnate the family dog,’ Ma said. ‘Now he’ll blow that bastardly trumpet.’

But before he could, the Ghost of Fury went off. First it was just a fountain of white sparks, but then it shot up higher and turned rose-pink. It started blowin off rockets that exploded in starbursts. By then the fountain of sparks on the end of our dock was at least twelve feet high and bright red. It shot off even more rockets, straight up into the sky, and they boomed as loud as a squadron of jets breakin the sound barrier. Ma covered her ears, but she was laughin fit to split. The fountain went down, then spurted up one last time – like an old man in a whorehouse, Ma said – and shot off this gorgeous red n yella flower into the sky.

There was a moment of silence – awed, don’t you know – and then everybody on the lake started applaudin like crazy. Some people who was in their campers tooted their horns, which sounded mighty thin after all those bangs. The Massimos was applaudin too, which showed they was good sports, which impressed me, because you know folks who have to win at everything usually ain’t. The one with the trumpet never took the damn thing out of its holster.

‘We did it!’ Ma shouted. ‘Alden, give your Ma a kiss!’

I did, and when I looked across the lake, I seen Paul Massimo standin at the end of his dock, in the light of those electric torches they had. He put up one finger, as if to say, ‘Wait and watch.’ It gave me a bad feelin in the pit of my stomach.

The son without the trumpet – the one I judged might have a lick of sense – put down a launcher cradle, slow and reverent, like an altar boy puttin out the Holy Communion. Settin in it was the biggest fuckin rocket I ever seen that wasn’t on TV at Cape Canaveral. Paul dropped down on one knee and put his lighter to the fuse. As soon as it started to spark, he grabbed both his boys and ran em right off the dock.

There was no pause, like with our Ghost of Fury. Fucker took off like Apollo 19, trailin a streak of blue fire that turned purple, then red. A second later the stars was blotted out by a giant flamin bird that covered the lake almost from one side to the other. It blazed up there, then exploded. And I’ll be damned if little birds didn’t come out of the explosion, shootin off in every direction.

The crowd went nuts. Them grown boys was huggin their father and poundin him on the back and laughin.

‘Let’s go in, Alden,’ Ma said, and she never sounded so sad since Daddy died. ‘We’re beat.’

‘We’ll get em next year,’ I said, pattin her shoulder.

‘No,’ she said, ‘them Massimos will always be a step ahead. That’s the kind of people they are – people with CONNECTIONS. We’re just a couple of poor folks livin on a lucky fortune, and I guess that’ll have to be enough.’

As we went up the steps of our shitty little cabin, there come one final trumpet blast from the fine big house across the lake: Waaaaaaaah! Made my head ache, it did.

Howard Gamache told me that last firework was called the Rooster of Destiny. He said he’d seen videos of em on YouTube, but always with people talkin Chinese in the background.

‘How this Massimo gentleman got it into this country is a mystery to me,’ Howard said. This was about a month later, toward the end of last summer, when I finally got up enough ambition to make the drive up to his two-story wigwam on Indian Island and tell him what happened – how we give em a good battle but still come off on the short end when all was said and told.

‘It’s no mystery to me,’ I said. ‘His friends in China prob’ly threw it in as an extra with his last load of opium. You know, a little gift to say thanks for doin business with us. Have you got anything that’ll top it? Ma’s awful depressed, Mr Gamache. She don’t want to compete next year, but I was thinkin if there was anything … you know, the topper to top all toppers … I’d pay as much as a thousand dollars. It’d be worth it just to see my ma smilin on Fourth of July night.’

Howard sat on his back steps with his knees stickin up around his ears like a couple of boulders – God, what a mighty man he was – and thought about it. Cogitated on it. Judged his way around it. At last he said, ‘I have heard rumors.’

‘Rumors about what?’

‘About a special something called Close Encounters of the Fourth Kind,’ he said. ‘From a fellow I correspond with on the subject of gunpowder amusements. His native name is Shining Path, but mostly he goes by Johnny Parker. He’s a Cayuga Indian, and he lives near Albany, New York. I could give you his email address, but he won’t reply unless I email him first, and tell him you’re safe.’

‘Will you do that?’ I asked.

‘Of course,’ he said, ‘but first you must pay heap big wampum, paleface. Fifty bucks should do it.’

Money passed from my small hand to his big one, he emailed Johnny Shining Path Parker, and when I got back to the lake and sent him an email of my own, he answered right back. But he wouldn’t talk about what he called CE4 except in person, claimed the government read all Native American emails as a matter of course. I didn’t have no argument with that; I bet those suckers read everyone’s email. So we agreed to meet, and along about the first of October last year, I went up.

Accourse Ma wanted to know what sort of errand would take me all the way to upstate New York, and I didn’t bother tellin her no made-up story, because she always sees through em and has since I was knee-high to a collie. She just shook her head. ‘Go on, if it’ll make you happy,’ she said. ‘But you know they’ll come back with somethin even bigger, and we’ll be stuck listenin to that Eye-Tie cock-knocker blow his trumpet.’

‘Well, maybe,’ I said, ‘but Mr Shining Path says this is the firework to end all fireworks.’

As you now see, that turned out to be nothing but the truth.

I had a pretty drive, and Johnny Shining Path Parker turned out to be a nice fella. His wigwam was in Green Island, where the houses are almost as big as the Massimos’ Twelve Pines, and his wife made one hell of an enchilada. I ate three with that hot green sauce and got the shits on the way home, but since that ain’t part of the story and I can see Ardelle’s gettin impatient again, I’ll leave it out. All I can say is thank God for Handi-Wipes.

‘CE4 would be a special order,’ Johnny said. ‘The Chinese make only three or four a year, in Outer Mongolia or someplace like that, where there’s snow nine months of the year and the babies are purportedly raised with wolf cubs. Such explosive devices are usually shipped to Toronto. I guess I could order one and bring it in from Canada myself, although you’d have to pay for my gas and my time, and if I got caught, I’d probably end up in Leavenworth as a terrorist.’

‘Jesus, I don’t want to get you in no trouble like that,’ I said.

‘Well, I’m exaggerating a bit, maybe,’ he said, ‘but CE4’s one hell of a firework. Never been one like it. I couldn’t give you your money back if your pal across the lake happened to have something to beat it, but I’d give you back my profit on the deal. That’s how sure I am.’

‘Besides,’ Cindy Shining Path Parker said, ‘Johnny loves an adventure. Would you like another enchilada, Mr McCausland?’

I passed on that, which probably kep me from explodin somewhere in Vermont, and for awhile I almost forgot the whole thing. Then, just after New Year’s – we’re gettin close now, Ardelle, don’t that make you happy? – I got a call from Johnny.

‘If you want that item we were discussing last fall,’ he said, ‘I’ve got it, but it’ll cost you two thousand.’

I sucked in breath. ‘That’s pretty steep.’

‘I can’t argue with you there, but look at it this way – you white folks got Manhattan for twenty-four bucks, and we’ve been looking for payback ever since.’ He laughed, then said, ‘But speaking seriously now, and if you don’t want it, that’s fine. Maybe your buddy across the lake would be interested.’

‘Don’t you ever,’ I said.

He laughed harder at that. ‘I have to tell you, this thing is pretty awesome. I’ve sold a lot of fireworks over the years, and I’ve never seen anything remotely like this.’

‘Like what?’ I asked. ‘What is it?’

‘You have to see for yourself,’ he said. ‘I have no intention of sending you a pitcher over the Internet. Besides, it doesn’t look like much until it’s … uh … in use. If you want to roll on up here, I can show you a video.’

‘I’ll be there,’ I said, and two or three days later I was, sober and shaved and with my hair combed.

Now listen to me, you two. I ain’t gonna make excuses for what I done – and you c’n leave Ma out of it, I was the one that got the damn thing, and I was the one who set it off – but I am gonna tell you that the CE4 I saw in that video Johnny showed me and the one I set off last night wasn’t the same. The one in the video was a lot smaller. I even remarked on the size of the crate mine was in when Johnny and me put it in the back of the truck. ‘They sure must have put a lot of packing in there,’ I said.

‘I guess they wanted to make sure nothing would happen to it in shipping,’ Johnny said.

He didn’t know either, you see. Cindy Shining Path asked if I didn’t want to at least open the crate and have a look, make sure it was the right thing, but it was nailed up tight all over, and I wanted to get back before dark, on account of my eyes ain’t as good as they used to be. But because I come here today determined to make a clean breast of it, I have to tell you that wasn’t the truth. Evenin is my drinkin time, and I didn’t want to miss any of it. That’s the truth. I know that’s kind of a sad way to be, and I know I have to do somethin about it. I guess if they put me in jail, I’ll get a chance, won’t I?

Me n Ma unnailed the crate the next day and took a look at what we’d bought. This was at the house in town, you understand, because we’re talkin January, and colder than a witch’s tit. There was some packin material, all right, Chinese newspapers of some kind, but not nearly so much as I expected. The CE4 was probably seven feet on the square, and looked like a package done up in brown paper, only the paper was kind of oily, and so heavy it felt more like canvas. The fuse was stickin out the bottom.

‘Do you think it will really go up?’ Ma asked.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘if ours don’t, what’s the worst that can happen?’

‘We’ll be out two thousand bucks,’ Ma said, ‘but that ain’t the worst. The worst’d be it rises up two or three feet and then fizzles into the lake. Followed by that young Eye-talian who looks like Ben Afflict blowin his trumpet.’

We put it in the garage and there it stayed until Memorial Day, when we took it out to the lake. I didn’t buy nothing else of a firework nature this year, not from Pop Anderson and not from Howard Gamache, either. We was all in on the one thing. It was CE4 or bust.

All right; here we are at last night. Fourth of July of oh-fifteen, never been nothin like it on Abenaki Lake and I hope there never will be again. We knew it had been a goddam dry summer, accourse we knew, but that never crossed our minds. Why would it? We were shootin over the water, weren’t we? What could be safer?

All the Massimos was there and havin fun – playin their music and playin their games and cookin weenies on about five different grills and swimmin near the beach and divin off the float. Everyone else was there, too, on both sides of the lake. There was even some at the north and south ends, where it’s all swampy. They were there to see this year’s chapter of the Great Fourth of July Arms Race, Eye-Ties versus Yankees.

Dusk drew down and finally the wishin star come out, like she always does, and those electric torches at the end of the Massimo dock popped on like a couple of spotlights. Out onto it struts Paul Massimo, flanked by his two grown sons, and goddam if they weren’t dressed like for a fancy country club dance! Father in a tuxedo, sons in white dinner jackets with red flowers in the lapels, the Ben Afflict-lookin one wearin his trumpet down low on his hip, like a gunslinger.

I looked around and seen the lake was lined with more folks than ever before. Must have been at least a thousand. They’d come expectin a show, and those Massimos was dressed to give em one, while Ma was in her usual housedress and I was in a pair of old jeans and a tee-shirt that said KISS ME WHERE IT STINKS, MEET ME IN MILLINOCKET.

‘He ain’t got no boxes, Alden,’ Ma said. ‘Why is that?’

I just shook my head, because I didn’t know. Our single firework was already at the end of our dock, covered with an old quilt. Had been there all day.

Massimo held out his hand to us, polite as always, tellin us we should start. I shook my head and held out mine right back, as if to say nope, after you this time, monsewer. He shrugged and made a twirlin gesture in the air, sort of like when the ump is sayin it’s a home run. About four seconds later, the night was filled with uprushin trails of sparks, and fireworks started to explode over the lake in starbursts and sprays and multiple canister blasts that shot out flowers and fountains and I don’t know what-all.

Ma gasped. ‘Why, that dirty dog! He went and hired a whole fireworks crew! Professionals!’

And yes, that’s just what he done. He must’ve spent ten or fifteen thousand dollars on that twenty-minute sky-show, what with the Double Excalibur and the Wolfpack that come near the end. The crowd on the lake was whoopin and hollerin to beat the band, bammin on their car horns and cheerin and screamin. The Ben Afflict-lookin one was blowin his trumpet hard enough to give him a brain hemorrhage, but you couldn’t even hear him over the gunnery practice goin on in the sky, which was lit up bright as day, and in every color. Sheets of smoke rose from where the fireworks crew was settin off their goods down on the beach, but none of it blew across the lake. It blew toward the house instead. Toward Twelve Pines. You could say I should have noticed that, but I didn’t. Ma didn’t, either. Nobody did. We was too gobsmacked. Massimo was sendin us a message, you see: It’s over. Don’t even think about it next year, you poor-ass Yankees.

There was a pause, and I was just decidin he’d shot his load when up goes a double gusher of sparks, and the sky filled with a great big burnin boat, sails n all! I knew from Howard Gamache what that one was too: an Excellent Junk. That’s a Chinese boat. When it finally went out and the crowd around the lake stopped goin bananas, Massimo signaled to his fireworks boys one last time and they sparked up an American flag on the beach. It burned red white n blue and threw off fireballs while someone played ‘America the Beautiful’ through the sound system.

Finally, the flag burned out to nothin but orange cinders. Massimo was still at the end of his dock, and he held his hand out to us again, smiling. As if to say, Go on n shoot whatever paltry shit you got over there, McCausland, and we’ll be done with it. Not just this year but for good.

I looked at Ma. She looked at me. Then she slatted whatever was left of her drink – we was drinkin Moonquakes last night – into the water and said, ‘Go on. It probably won’t amount to a pisshole in the snow, but we bought the damn thing, might as well set her off.’

I remember how quiet it was. The frogs hadn’t started up again yet, and the poor old loons had packed it in for the night, maybe for the rest of the summer. There was still plenty of people standin at the water’s edge to see what we had, but a lot more was goin back to town, like fans will when their team is gettin blown out and has no chance of comin back. I could see a chain of lights all the way down Lake Road, that hooks up with Highway 119, and to Pretty Bitch, the one that eventually takes you to TR-90 and Chester’s Mill.

I decided if I was gonna do it, I ought to make a fair show of it; if it misfired, the ones that were left could laugh as much as they wanted. I could even put up with the goddam trumpet, knowin I wouldn’t have to listen to it blowed at me next year, because I was done, and I could see from her face that Ma felt the same. Even her boobs seemed to be hangin their heads, but maybe that was just because she left off her bra last night. She says it pinches her terrible.

I whipped off that piece of quilt like a magician doin a trick, and there was the square thing I’d bought for two thousand dollars – prob’ly half what Massimo paid for just his Excellent Junk alone – all wrapped in its heavy canvasy paper, with the short thick fuse stickin out the end.

I pointed to it, then pointed to the sky. Them three dressed-up Massimos standin at the end of their dock laughed, and the trumpet blew: Waaaa-aaaaah!

I lit the fuse and it started to spark. I grabbed Ma and pulled her back, in case the friggin thing should explode on the launchin pad. The fuse burned down to the box, then disappeared. Fuckin box just sat there. The Massimo with the trumpet raised it to his lips, but before he could blow it, fire kind of squashed out from under the box and up she rose, slow at first, then faster as more jets – I guess they was jets – caught fire.

Up n up. Ten feet, then twenty, then forty. I could just make out the square shape against the stars. It made fifty, everyone cranin their necks to look, and then it exploded, just like the one in the YouTube video Johnny Shining Path Parker showed me. Me n Ma cheered. Everyone cheered. The Massimos only looked perplexed, and maybe – hard to tell from our side of the lake – a little contemptuous. It was like they was thinkin, an exploding box, what the fuck is that?

Only the CE4 wasn’t done. When people’s eyes adjusted, they gasped in wonder, for the paper stuff was unfoldin and spreadin even as it began to burn every color you ever saw and some you never did. It was turnin into a goddam flyin saucer. It spread and spread, like God was openin his own holy umbrella, and as it opened it began shootin off fireballs every whichway. Each one exploded and shot off more, makin a kind of rainbow over that saucer. I know you two have seen cell phone video of it, probably everybody who had a phone was makin movies of it which I don’t doubt will be evidence at my trial, but I’m tellin you you had to be there to fully appreciate the wonder of it.

Ma was clutchin my arm. ‘It’s beautiful,’ she said, ‘but I thought it was only eight feet across. Isn’t that what your Indian friend said?’

It was, but the thing I’d unleashed was twenty feet across and still growin when it popped a dozen or more little parachutes to keep it elevated while it shot off more colors and sparklers and fountains and flash bombs. It was maybe not so grand as Massimo’s fireworks show in the altogether, but grander than his Excellent Junk. And, accourse, it came last. That’s what people always remember, don’t you think, what they see last?

Ma seen the Massimos starin up at the sky, their jaws hung down like doors on busted hinges, lookin like the purest goddam ijits that ever walked the earth, and she started to dance. The trumpet was danglin down Ben Afflict’s hand, like he’d forgotten he had it.

‘We beat em!’ Ma screamed at me, shakin her fists. ‘We finally did it, Alden! Look at em! They’re beat and it was worth every fuckin penny!’

She wanted me to dance with her, but I seen something I didn’t much care for. The wind was pushin that flyin saucer east’rds across the lake, toward Twelve Pines.

Paul Massimo seen the same thing and pointed at me, as if to say, You put it up there, you bring it down while it’s still over the water.

Only I couldn’t, accourse, and meanwhile the goddam thing was still blowin its wad, shootin off rockets and cannonades and swirly fountains like it would never stop. Then – I had no idea it was gonna happen, because the video Johnny Shining Path showed me was silent – it started to play music. Just five notes over and over: doo-dee-doo-dum-dee. It was the music the spaceship makes in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. So it’s toodlee-dooin and toodlee-deein, and that’s when the goddam saucer caught afire. I don’t know if that was an accident or if it was s’posed to be the final effect. The parachutes holdin it up, they caught, too, and the whoremaster started to sink. At first I thought it’d go down before it ran out of lake to land in, maybe even on the Massimos’ swimmin float, which would’ve been bad, but not the worst. Only just then a stronger gust of wind blew up, as if Mother Nature herself was tired of the Massimos. Or maybe it was just that fuckin trumpet the old girl was tired of.

Well, you know how their place got its name, and them dozen pines was plenty dry. There was two of em on either side of the long front porch, and those were what our CE4 crashed into. Them trees went up right away, lookin sort of like the electric torches at the end of Massimo’s dock, only bigger. First the needles, then the branches, then the trunks. Massimos started runnin every whichway, like ants when someone kicks their hill. A burnin branch fell on the roof over the porch, and pretty soon that was burnin merry hell, too. And all the while that little tootlin tune went on, doo-dee-doo-dum-dee.

The spaceship tore in two pieces. Half of it fell on the lawn, which wasn’t s’bad, but the other half floated down on the main roof, still shootin off a few final rockets, one of which crashed through an upstairs window, lightin the curtains afire as it went.

Ma turned to me and said, ‘Well, that ain’t good.’

‘No,’ I said, ‘looks pretty poor, don’t it?’

She said, ‘I guess you better call the fire department, Alden. In fact, I guess you better call two or three of em, or there’s gonna be cooked woods from the lake to the Castle County line.’

I turned to run back to the cabin and get my phone, but she caught my arm. There was this funny little smile on her face. ‘Before you go,’ she said, ‘take a glance at that.’

She pointed across the lake. By then the whole house was afire, so there wasn’t no trouble seein what she was pointin at. There was no one on their dock anymore, but one thing got left behind: the goddam trumpet.

‘Tell em it was all my idea,’ Ma said. ‘I’ll go to jail for it, but I don’t give a shit. At least we shut that friggin thing up.’

Say, Ardelle, can I have a drink of water? I’m dry as an old chip.

Officer Benoit brought Alden a glass of water. She and Andy Clutterbuck watched him drink it down – a lanky man in chinos and a strap-style tee-shirt, his hair thin and graying, his face haggard from lack of sleep and the previous night’s ingestion of sixty-proof Moonquakes.

‘At least no one got hurt,’ Alden said. ‘I’m glad of that. And we didn’t burn the woods down. I’m glad of that, too.’

‘You’re lucky the wind died,’ Andy said.

‘You’re also lucky the fire trucks from all three towns were standing by,’ Ardelle added. ‘Of course they have to be on Fourth of July nights, because there are always a few fools setting off drunken fireworks.’

‘This is all on me,’ Alden said. ‘I just want you to understand that. I bought the goddam thing, and I was the one who fired it up. Ma had nothing to do with it.’ He paused. ‘I just hope Massimo understands that, and leaves my Ma alone. He’s CONNECTED, you know.’

Andy said, ‘That family has been summering on Abenaki Lake for twenty years or more, and according to everything I know, Paul Massimo is a legitimate businessman.’

‘Ayuh,’ Alden said. ‘Just like Al Capone.’

Officer Ellis knocked on the glass of the interview room, pointed at Andy, cocked his thumb and little finger in a telephone gesture, and beckoned. Andy sighed and left the room.

Ardelle Benoit stared at Alden. ‘I’ve seen some tall orders of shit flapjacks in my time,’ she said, ‘and even more since I got on the cops, but this takes the prize.’

‘I know,’ Alden said, hanging his head. ‘I ain’t makin any excuses.’ Then he brightened. ‘But it was one hell of a show while it lasted. People won’t never forget it.’

Ardelle made a rude noise. Somewhere in the distance, a siren howled.

Andy eventually came back and sat down. He said nothing at first, just looked off into space.

‘Was that about Ma?’ Alden asked.

‘It was your ma,’ Andy said. ‘She wanted to talk to you, and when I told her you were otherwise occupied, she asked if I would pass on a message. She was calling from Lucky’s Diner, where she just finished having a nice sit-down brunch with your neighbor from across the lake. She said to tell you he was still dressed in his tuxedo and it was his treat.’

‘Did he threaten her?’ Alden cried. ‘Did that sonofabitch—’

‘Sit down, Alden. Relax.’

Alden settled slowly from a half-risen crouch, but his hands were clenched into fists. They were big hands, and looked capable of doing damage, if their owner felt provoked.

‘Hallie also said to tell you that Mr Massimo isn’t going to press any charges. He said that two families got into a stupid competition, and consequently both families were at fault. Your mother says Mr Massimo wants to let bygones be bygones.’

Alden’s Adam’s apple bobbed up and down, reminding Ardelle of a monkey-on-a-stick toy she’d had as a child.

Andy leaned forward. He was smiling in the painful way folks do when they don’t really want to smile but just can’t help it. ‘She said Mr Massimo also wants you to know he was sorry about what happened with the rest of your fireworks.’

‘The rest of em? I told you we didn’t have nothing this year except for—’

‘Hush while I’m talking. I don’t want to forget any of the message.’