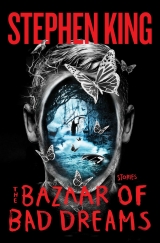

Текст книги "The Bazaar of Bad Dreams"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

‘Yuh,’ he says, like a man confirming something he was pretty sure of in the first place. ‘Billy can hit here.’

‘Good,’ I tell him. It’s all I can think of to say.

‘Good,’ he says back. Then – I swear – he says, ‘Do you think those guys need help with them hoses?’

I laughed. There was something strange about him, something off, something that made folks nervous … but that something made people take to him too. Kinda sweet. Something that made you want to like him in spite of feeling he wasn’t exactly all there. Joe DiPunno knew he was light in the head right away. Some of the players did too, but that didn’t stop them from liking him. I don’t know, it was like when you talked to him what came back was the sound of your own voice. Like an echo in a cave.

‘Billy,’ I said, ‘groundskeeping ain’t your job. Your job is to put on the gear and catch Danny Dusen this afternoon.’

‘Danny Doo,’ he said.

‘That’s right. Twenty and six last year, should have won the Cy Young, didn’t. Because the writers don’t like him. He’s still got a red ass over that. And remember this: if he shakes you off, don’t you dare flash the same sign again. Not unless you want your pecker and asshole to change places after the game, that is. Danny Doo is four games from two hundred wins, and he’s going to be mean as hell until he gets there.’

‘Until he gets there.’ Nodding his head.

‘That’s right.’

‘If he shakes me off, flash something different.’

‘Yes.’

‘Does he have a changeup?’

‘Does a dog piss on a fire hydrant? The Doo’s won a hundred and ninety-six games. You don’t do that without a changeup.’

‘Not without a changeup,’ he says. ‘Okay.’

‘And don’t get hurt out there. Until the front office can make a deal, you’re what we got.’

‘I’m it,’ he says. ‘Gotcha.’

‘I hope so.’

Other players were coming in by then, and I had about a thousand things to do. Later on I saw the kid in Jersey Joe’s office, signing whatever needed to be signed. Kerwin McCaslin hung over him like a vulture over roadkill, pointing out all the right places. Poor kid, probably six hours’ worth of sleep in the last sixty, and he was in there signing five years of his life away. Later I saw him with Dusen, going over the Boston lineup. The Doo was doing all the talking, and the kid was doing all the listening. Didn’t even ask a question, so far as I saw, which was good. If the kid had opened his head, Danny probably would have bit it off.

About an hour before the game, I went in to Joe’s office to look at the lineup card. He had the kid batting eighth, which was no shock. Over our heads the murmuring had started and you could hear the rumble of feet on the boards. Opening Day crowds always pile in early. Listening to it started the butterflies in my gut, like always, and I could see Jersey Joe felt the same. His ashtray was already overflowing.

‘He’s not big like I hoped he’d be,’ he said, tapping Blakely’s name on the lineup card. ‘God help us if he gets cleaned out.’

‘McCaslin hasn’t found anyone else?’

‘Maybe. He talked to Hubie Rattner’s wife, but Hubie’s on a fishing trip somewhere in Rectal Thermometer, Wisconsin. Out of touch until next week.’

‘Hubie Rattner’s forty-three if he’s a day.’

‘Tell me somethin I don’t know. But beggars can’t be choosers. And be straight with me – how long do you think that kid’s gonna last in the bigs?’

‘Oh, he’s probably just a cup of coffee,’ I says, ‘but he’s got something Faraday didn’t.’

‘And what might that be?’

‘Dunno. But if you’d seen him standing behind the plate and looking out into center, you might feel better about him. It was like he was thinking “This ain’t the big deal I thought it would be.”’

‘He’ll find out how big a deal it is the first time Ike Delock throws one at his nose,’ Joe said, and lit a cigarette. He took a drag and started hacking. ‘I got to quit these Luckies. Not a cough in a carload, my ass. I’ll bet you twenty goddam bucks that kid lets Danny Doo’s first curve go right through his wickets. Then Danny’ll be all upset – you know how he gets when someone fucks up his train ride – and Boston’ll be off to the races.’

‘Ain’t you the cheeriest Cheerio,’ I says.

He stuck out his hand. ‘Twenty bucks. Bet.’

And because I knew he was trying to take the curse off it, I shook his hand. That was twenty I won, because the legend of Blockade Billy started that very day.

You couldn’t say he called a good game, because he didn’t call it. The Doo did that. But the first pitch – to Frank Malzone – was a curve, and the kid caught it just fine. Not only that, though. It was a cunt’s hair outside and I never saw a catcher pull one back so fast, not even Yogi. Ump called strike one and it was us off to the races, at least until Williams hit a solo shot in the fifth. We got that back in the sixth, when Ben Vincent put one out. Then in the seventh, we’ve got a runner on second – I think it was Barbarino – with two outs and the new kid at the plate. It was his third at bat. First time he struck out looking, the second time swinging. Delock fooled him bad that time, made him look silly, and the kid heard the only boos he ever got while he was wearing a Titans uniform.

He steps in, and I looked over at Joe. Seen him sitting way down by the water cooler, just looking at his shoes and shaking his head. Even if the kid worked a walk, The Doo was up next, and The Doo couldn’t hit a slowpitch softball with a tennis racket. As a hitter that guy was fucking terrible.

I won’t drag out the suspense; this ain’t no kids’ sports comic. Although whoever said life sometimes imitates art was right, and it did that day. Count went to three and two. Then Delock threw the sinker that fooled the kid so bad the first time and damn if the kid didn’t suck for it again. Except Ike Delock turned out to be the sucker that time. Kid golfed it right off his shoetops the way Ellie Howard used to do and shot it into the gap. I waved the runner in and we had the lead back, two to one.

Everybody in the joint was on their feet, screaming their throats out, but the kid didn’t even seem to hear it. Just stood there on second, dusting the seat of his pants. He didn’t stay there long, because The Doo went down on three pitches, then threw his bat like he always did when he got struck out.

So maybe it’s a sports comic after all, like the kind you probably read behind your history book in junior high school study hall. Top of the ninth and The Doo’s looking at the top of the lineup. Strikes out Malzone, and a quarter of the crowd’s on their feet. Strikes out Klaus, and half the crowd’s on their feet. Then comes Williams – old Teddy Ballgame. The Doo gets him on the hip, oh and two, then weakens and walks him. The kid starts out to the mound and Doo waves him back – just squat and do your job, sonny. So sonny does. What else is he gonna do? The guy on the mound is one of the best pitchers in baseball and the guy behind the plate was maybe playing a little pickup ball behind the barn that spring to keep in shape after the day’s bovine tits was all pulled.

First pitch, goddam! Williams takes off for second. The ball was in the dirt, hard to handle, but the kid still made one fuck of a good throw. Almost got Teddy, but as you know, almost only counts in horseshoes. Now everybody’s on their feet, screaming. The Doo does some shouting at the kid – like it was the kid’s fault instead of just a bullshit pitch – and while Doo’s telling the kid he’s a lousy choker, Williams calls time. Hurt his knee a little sliding into the bag, which shouldn’t have surprised anyone; he could hit like nobody’s business, but he was a leadfoot on the bases. Why he stole a bag that day is anybody’s guess. It sure wasn’t no hit-and-run, not with two outs and the game on the line.

So Billy Anderson comes in to run for Teddy and Dick Gernert steps into the box, .425 slugging percentage or something like it. The crowd’s going apeshit, the flag’s blowing out, the frank wrappers are swirling around, women are goddam crying, men are yelling for Jersey Joe to yank The Doo and put in Stew Rankin – he was what people would call the closer today, although back then he was just known as a short-relief specialist.

But Joe crossed his fingers and stuck with Dusen.

The count goes three and two, right? Anderson off with the pitch, right? Because he can run like the wind and the guy behind the plate’s a first-game rook. Gernert, that mighty man, gets just under a curve and beeps it – not bloops it but beeps it – behind the pitcher’s mound, just out of The Doo’s reach. He’s on it like a cat, though. Anderson’s around third and The Doo throws home from his knees. That thing was a fucking bullet.

I know what you’re thinking, Mr King, but you’re dead wrong. It never crossed my mind that our new rookie catcher was going to get busted up like Faraday and have a nice one-game career in the bigs. For one thing, Billy Anderson was no moose like Big Klew; more of a ballet dancer. For another … well … the kid was better than Faraday. I think I sensed that as soon as I saw him sitting on the bumper of his beshitted old Hiram Hoehandle truck with his wore-out gear stored in the back.

Dusen’s throw was low but on the money. The kid took it between his legs, then pivoted around, and I seen he was holding out just the mitt. I just had time to think of what a rookie mistake that was, how he forgot that old saying two hands for beginners, how Anderson was going to knock the ball loose and we’d have to try to win the game in the bottom of the ninth. But then the kid lowered his left shoulder like a football lineman. I never paid attention to his free hand, because I was staring at that outstretched catcher’s mitt, just like everyone else in Old Swampy that day. So I didn’t exactly see what happened, and neither did anybody else.

What I saw was this: the kid whapped the glove on Anderson’s chest while he was still three full steps from the dish. Then Anderson hit the kid’s lowered shoulder. Anderson went ass over teakettle and landed behind the left-hand batter’s box. The umpire lifted his fist in the out sign. Then Anderson started to yell and grab his ankle. I could hear it from the third-base coach’s box, so you know it must have been good yelling, because those Opening Day fans were roaring like a force-ten gale. I could see that Anderson’s left pants cuff was turning red, and blood was oozing out between his fingers.

Can I have a drink of water? Just pour some out of that plastic pitcher, would you? Plastic pitchers is all they give us for our rooms, you know; no glass pitchers allowed in the zombie hotel.

Ah, that’s good. Been a long time since I talked so much, and I got a lot more to say. You bored yet? No? Good. Me neither. Having the time of my life, awful story or not.

Billy Anderson didn’t play again until ’58, and ’58 was his last year – Boston gave him his unconditional release halfway through the season, and he couldn’t catch on with anyone else. Because his speed was gone, and speed was really all he had to sell. The docs said he’d be good as new, the Achilles tendon was only nicked, not cut all the way through, but it was also stretched, and I imagine that’s what finished him. Baseball’s a tender game, you know; people don’t realize. And it isn’t only catchers who get hurt in collisions at the plate.

After the game, Danny Doo grabs the kid in the shower and yells: ‘I’m gonna buy you a drink tonight, rook! In fact, I’m gonna buy you ten!’ And then he gives his highest praise: ‘You hung the fuck in there!’

‘Ten drinks, because I hung the fuck in there,’ the kid says, and The Doo laughs and claps him on the back like it’s the funniest thing he ever heard.

But then Pinky Higgins comes storming in. He was managing the Red Sox that year, which was a thankless job; things only got worse for Pinky and for Sox as the summer of ’57 crawled along. He was mad as hell, chewing a wad of tobacco so hard and fast the juice squirted from both sides of his mouth and splattered his uniform. He said the kid had deliberately cut Anderson’s ankle when they collided at the plate. Said Blakely must have done it with his fingernails, and the kid should be put out of the game for it. This was pretty rich, coming from a man whose motto was ‘Spikes high and let em die!’

I was sitting in Joe’s office drinking a beer, so me and DiPunno listened to Pinky’s rant together. I thought the guy was nuts, and I could see from Joe’s face that I wasn’t alone.

Joe waited until Pinky ran down, then said, ‘I wasn’t watching Anderson’s foot. I was watching to see if Blakely made the tag and held onto the ball. Which he did.’

‘Get him in here,’ Pinky fumes. ‘I want to say it to his face.’

‘Be reasonable, Pink,’ Joe says. ‘Would I be in your office doing a tantrum if it had been Blakely all cut up?’

‘It wasn’t spikes!’ Pinky yells. ‘Spikes are a part of the game! Scratching someone up like a … a girl in a kickball match … that ain’t! And Anderson’s in the game seven years! He’s got a family to support!’

‘So you’re saying what? My catcher ripped your pinch runner’s ankle open while he was tagging him out – and tossing him over his goddam shoulder, don’t forget – and he did it with his nails?’

‘That’s what Anderson says,’ Pinky tells him. ‘Anderson says he felt it.’

‘Maybe Blakely stretched Anderson’s foot with his nails, too. Is that it?’

‘No,’ Pinky admits. His face was all red by then, and not just from being mad. He knew how it sounded. ‘He says that happened when he came down.’

‘Begging the court’s pardon,’ I says, ‘but fingernails? This is a load of crap.’

‘I want to see the kid’s hands,’ Pinky says. ‘You show me or I’ll lodge a goddam protest.’

I thought Joe would tell Pinky to shit in his hat, but he didn’t. He turned to me. ‘Tell the kid to come in here. Tell him he’s gonna show Mr Higgins his nails, just like he did to his first-grade teacher after the Pledge of Allegiance.’

I got the kid. He came willingly enough, although he was just wearing a towel, and didn’t hold back showing his nails. They were short, clean, not broken, not even bent. There were no blood blisters, either, like there might be if you really set them in someone and raked with them. One little thing I did happen to notice, although I didn’t think anything of it at the time: the Band-Aid was gone from his second finger, and I didn’t see any sign of a healing cut where it had been, just clean skin, pink from the shower.

‘Satisfied?’ Joe asked Pinky. ‘Or would you like to check his ears for potato-dirt?’

‘Fuck you,’ Pinky says. He got up, stamped over to the door, spat his cud into the wastepaper basket there – splut! – and then he turns back. ‘My boy says your boy cut him. Says he felt it. And my boy don’t lie.’

‘Your boy tried to be a hero with the game on the line instead of stopping at third and giving Piersall a chance. He’d tell you the shitstreak in his skivvies was chocolate sauce if it’d get him off the hook for that. You know what happened and so do I. Anderson got tangled in his own spikes and did it to himself when he went whoopsy-daisy. Now get out of here.’

‘There’ll be a payback for this, DiPunno.’

‘Yeah? Well, it’s the same game time tomorrow. Get here early while the popcorn’s hot and the beer’s still cold.’

Pinky left, already tearing off a fresh piece of chew. Joe drummed his fingers beside his ashtray, then asked the kid: ‘Now that it’s just us chickens, did you do anything to Anderson? Tell me the truth.’

‘No.’ Not a bit of hesitation. ‘I didn’t do anything to Anderson. That’s the truth.’

‘Okay,’ Joe said, and stood up. ‘Always nice to shoot the shit after a game, but I think I’ll go on home and fuck my wife on the sofa. Winning on Opening Day always makes my pecker stand up.’ He clapped our new catcher on the shoulder. ‘Kid, you played the game the way it’s supposed to be played. Good for you.’

He left. The kid cinched his towel around his waist and started back to the locker room. I said, ‘I see that shaving cut’s all better.’

He stopped dead in the doorway, and although his back was to me, I knew he’d done something out there. The truth was in the way he was standing. I don’t know how to explain it better, but … I knew.

‘What?’ Like he didn’t get me, you know.

‘The shaving cut on your finger.’

‘Oh, that shaving cut. Yuh, all better.’

And out he sails … although, rube that he was, he probably didn’t have a clue where he was going.

Okay, second game of the season. Dandy Dave Sisler on the mound for Boston, and our new catcher is hardly settled into the batter’s box before Sisler chucks a fastball at his head. Would have knocked his fucking eyes out if it had connected, but he snaps his head back – didn’t duck or nothing – and then just cocks his bat again, looking at Sisler as if to say, Go on, Mac, do it again if you want.

The crowd’s screaming like mad and chanting RUN IM! RUN IM! RUN IM! The ump didn’t run Sisler, but he got warned and a cheer went up. I looked over and saw Pinky in the Boston dugout, walking back and forth with his arms folded so tight he looked like he was trying to keep from exploding.

Sisler walks twice around the mound, soaking up the fan-love – boy oh boy, they wanted him drawn and quartered – and then he went to the rosin bag, and then he shook off two or three signs. Taking his time, you know, letting it sink in. The kid all the time just standing there with his bat cocked, comfortable as your gramma squatting on the living room sofa. So Dandy Dave throws a get-me-over fastball right down Broadway and the kid loses it in the left-field bleachers. Tidings was on base and we’re up two to nothing. I bet the people over in New York heard the noise from Swampy when the kid hit that home run.

I thought he’d be grinning when he came around third, but he looked just as serious as a judge. Under his breath he’s muttering, ‘Got it done, Billy, showed that busher and got it done.’

The Doo was the first one to grab him in the dugout and danced him right into the bat rack. Helped him pick up the spilled lumber, too, which was nothing like Danny Dusen, who usually thought he was above such things.

After beating Boston twice and pissing off Pinky Higgins, we went down to Washington and won three straight. The kid hit safe in all three, including his second home run, but Griffith Stadium was a depressing place to play, brother; you could have machine-gunned a running rat in the box seats behind home plate and not had to worry about hitting any fans. Goddam Senators finished over forty back that year. Jesus fucking wept.

The kid was behind the plate for The Doo’s second start down there and damn near caught a no-hitter in his fifth game wearing a big-league uniform. Pete Runnels spoiled it in the ninth – hit a double with one out. After that, the kid went out to the mound, and that time Danny didn’t wave him back. They discussed it a little bit, and then The Doo gave an intentional pass to the next batter, Lou Berberet (see how it all comes back?). That brought up Bob Usher, and he hit into a double play just as sweet as you could ever want: ball game.

That night The Doo and the kid went out to celebrate Dusen’s one hundred and ninety-eighth win. When I saw our newest chick the next day, he was very badly hungover, but he bore that as calmly as he bore having Dave Sisler chuck at his head. I was starting to think we had a real big leaguer on our hands, and wouldn’t be needing Hubie Rattner after all. Or anybody else.

‘You and Danny are getting pretty tight, I guess,’ I says.

‘Tight,’ he agrees, rubbing his temples. ‘Me and The Doo are tight. He says Billy’s his good luck charm.’

‘Does he, now?’

‘Yuh. He says if we stick together, he’ll win twenty-five and they’ll have to give him the Cy Young even if the writers do hate his guts.’

‘That right?’

‘Yessir, that’s right. Granny?’

‘What?’

He was giving me that wide blue stare of his: twenty-twenty vision that saw everything and understood almost nothing. By then I knew he could hardly read, and the only movie he’d ever seen was Bambi. He said he went with the other kids from Ottershow or Outershow – whatever – and I assumed it was his school. I was both right and wrong about that, but it ain’t really the point. The point is that he knew how to play baseball – instinctively, I’d say – but otherwise he was a blackboard with nothing written on it.

‘Tell me again what’s a Cy Young?’

That’s how he was, you see.

We went over to Baltimore for three before going back home. Typical spring baseball in that town, which isn’t quite south or north; cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey the first day, hotter than hell the second, a fine drizzle like liquid ice the third. Didn’t matter to the kid; he hit in all three games, making it eight straight. Also, he stopped another runner at the plate. We lost the game, but it was a hell of a stop. Gus Triandos was the victim, I think. He ran headfirst into the kid’s knees and just lay there as stunned, three feet from home. The kid put the tag on the back of his neck just as gentle as Mommy patting oil on Baby Dear’s sunburn.

There was a picture of that putout in the Newark Evening News, with a caption reading Blockade Billy Blakely Saves Another Run. It was a good nickname, and caught on with the fans. They weren’t as demonstrative in those days – nobody would have come to Yankee Stadium in ’57 wearing a chef’s hat to support Garry Sheffield, I don’t think – but when we played our first game back at Old Swampy, some of the fans came in carrying orange road-signs reading DETOUR and ROAD CLOSED.

The signs might have been a one-day thing if two Indians hadn’t got thrown out at the plate in our first game back. That was a game Danny Dusen pitched, incidentally. Both of those putouts were the result of great throws rather than great blocks, but the rook got the credit, anyway, and in a way he deserved it. The guys were starting to trust him, see? Also, they wanted to watch him slap the tag. Baseball players are fans too, and when someone’s on a roll, even the most hard-hearted try to help.

Dusen got his hundred and ninety-ninth that day. Oh, and the kid went three-for-four, including a home run, so it shouldn’t surprise you that even more people showed up with those signs for our second game against Cleveland.

By the third one, some enterprising fellow was selling them out on Titan Esplanade, big orange cardboard diamonds with black letters: ROAD CLOSED BY ORDER OF BLOCKADE BILLY. Some of the fans’d hold em up when Billy was at bat, and they’d all hold them up when the other team had a runner on third. By the time the Yankees came to town – this was going on to the end of April – the whole stadium would flush orange when the Bombers had a runner on third, which they did often in that series.

Because the Yankees kicked the living shit out of us and took over first place. It was no fault of the kid’s; he hit in every game and tagged out Bill Skowron between home and third when the lug got caught in a rundown. Skowron was a moose the size of Big Klew, and he tried to flatten the kid, but it was Skowron who went on his ass, the kid straddling him with a knee on either side. The photo of that one in the paper made it look like the end of a Big Time Wrestling match with Pretty Tony Baba for once finishing off Gorgeous George instead of the other way around. The crowd outdid themselves waving those ROAD CLOSED signs around. It didn’t seem to matter that the Titans had lost; the fans went home happy because they’d seen our skinny catcher knock Mighty Moose Skowron on his ass.

I seen the kid afterward, sitting naked on the bench outside the showers. He had a big bruise coming on the side of his chest, but he didn’t seem to mind it at all. He was no crybaby. He was too dumb to feel pain, some people said later; too dumb and crazy. But I’ve known plenty of dumb players in my time, and being dumb never stopped them from bitching over their ouchies.

‘How about all those signs, kid?’ I asked, thinking I would cheer him up if he needed cheering.

‘What signs?’ he says, and I could see by the puzzled look on his face that he wasn’t joking a bit. That was Blockade Billy for you. He would have stood in front of a semi if the guy behind the wheel was driving it down the third base line and trying to score on him, but otherwise he didn’t have a fucking clue.

We played a two-game series with Detroit before hitting the road again, and lost both. Danny Doo was on the mound for the second one, and he couldn’t blame the kid for the way it went; he was gone before the third inning was over. Sat in the dugout whining about the cold weather (it wasn’t cold), the way Harrington dropped a fly ball out in right (Harrington would have needed stilts to get to that one), and the bad calls he got from that sonofabitch Wenders behind the plate. On that last one he might have had a point. Hi Wenders didn’t like The Doo any more than the sportswriters did, never had, ran him in two ball games the year before. But I didn’t see any bad calls that day, and I was standing less than ninety feet away.

The kid hit safe in both games, including a home run and a triple. Nor did Dusen hold the hot bat against him, which would have been his ordinary behavior; he was one of those guys who wanted fellows to understand there was one big star on the Titans, and it wasn’t them. But he liked the kid; really seemed to think the kid was his lucky charm. And the kid liked him. They went barhopping after the game, had about a thousand drinks and visited a whorehouse to celebrate The Doo’s first loss of the season, and showed up the next day for the trip to KC pale and shaky.

‘The kid got laid last night,’ Doo confided in me as we rode out to the airport in the team bus. ‘I think it was his first time. That’s the good news. The bad news is that I don’t think he remembers it.’

We had a bumpy plane ride; most of them were back then. Lousy prop-driven buckets, it’s a wonder we didn’t all get killed like Buddy Holly and the Big Fucking Bopper. The kid spent most of the trip throwing up in the can at the back of the plane, while right outside the door a bunch of guys sat playing acey-deucey and tossing him the usual funny stuff: Get any onya? Want a fork and knife to cut that up a little? Then the next day the kid goes five-for-five at Municipal Stadium, including a pair of jacks.

There was also another Blockade Billy play; by then he could have taken out a patent. The latest victim was Cletus Boyer. Again it was Blockade Billy down with the left shoulder, and up and over Mr Boyer went, landing flat on his back in the left batter’s box. There were some differences, though. The rook used both hands on the tag, and there was no bloody foot or strained Achilles tendon. Boyer just got up and walked back to the dugout, dusting his ass and shaking his head like he didn’t quite know where he was. Oh, and we lost the game in spite of the kid’s five hits. Eleven to ten was the final score, or something like that. Ganzie Burgess’s knuckleball wasn’t dancing that day; the Athletics feasted on it.

We won the next game, and lost a squeaker on getaway day. The kid hit in both games, which made it sixteen straight. Plus nine putouts at the plate. Nine in sixteen games! That might be a record. If it was in the books, that is.

We went to Chicago for three, and the kid hit in those games, too, making it nineteen straight. But damn if we didn’t lose all three. Jersey Joe looked at me after the last of those games and said, ‘I don’t buy that lucky charm stuff. I think Blakely sucks luck.’

‘That ain’t fair and you know it,’ I said. ‘We were going good at the start, and now we’re in a bad patch. It’ll even out.’

‘Maybe,’ he says. ‘Is Dusen still trying to teach the kid how to drink?’

‘Yeah. They headed off to The Loop with some other guys.’

‘But they’ll come back together,’ Joe says. ‘I don’t get it. By now Dusen should hate that kid. Doo’s been here five years and I know his MO.’

I did, too. When The Doo lost, he had to lay the blame on somebody else, like that bum Johnny Harrington or that busher bluesuit Hi Wenders. The kid’s turn in the barrel was overdue, but Danny was still clapping him on the back and promising him he’d be Rookie of the Goddam Year. Not that The Doo could blame the kid for that day’s loss. In the fifth inning of his latest masterpiece, Danny had hucked one to the backstop in the fifth: high, wide, and handsome. That scored one. So then he gets mad, loses his control, and walks the next two. Then Nellie Fox doubled down the line. After that The Doo got it back together, but by then it was too late; he was on the hook and stayed there.

We got a little well in Detroit, took two out of three. The kid hit in all three games and made another one of those amazing home-plate stands. Then we flew home. By then the kid from the Davenport Cornholers was the hottest goddam thing in the American League. There was talk of him doing a Gillette ad.

‘That’s an ad I’d like to see,’ Si Barbarino said. ‘I’m a fan of comedy.’

‘Then you must love looking at yourself in the mirror,’ Critter Hayward said.

‘You’re a card,’ Si says. ‘What I mean is the kid ain’t got no whiskers.’

There never was an ad, of course. Blockade Billy’s career as a baseball player was almost over.

We had three scheduled with the White Sox, but the first one was a washout. The Doo’s old pal Hi Wenders was the umpire crew chief, and he gave me the news himself. I’d got to The Swamp early because the trunks with our road uniforms in them got sent to Idlewild by mistake and I wanted to make sure they’d been trucked over. We wouldn’t need them for a week, but I was never easy in my mind until such things were taken care of.

Wenders was sitting on a little stool outside the umpire’s room, reading a paperback with a blond in fancy lingerie on the cover.

‘That your wife, Hi?’ I asks.

‘My girlfriend,’ he says. ‘Go on home, Granny. Weather forecast says that by three it’s gonna be coming down in buckets. I’m just waiting for DiPunno and Lopez to call the game.’