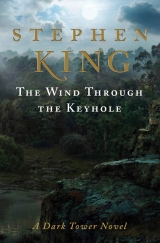

Текст книги "The Wind Through the Keyhole"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

We tethered our mounts away from the wind and sat on the floor inside the lean-to with our backs against the wall. I had dried beef wrapped in leaves in my saddlebag. The meat was salty, but my waterskin was full. The boy ate half a dozen chunks of the meat, tearing off big bites and washing them down with water.

A strong gust of wind shook the lean-to. Millie blatted a protest and fell silent.

“It’ll be a full-going simoom by dark,” Young Bill said. “You watch and see if it ain’t.”

“I like the sound of the wind,” I said. “It makes me think of a story my mother read to me when I was a sma’ one. ‘The Wind Through the Keyhole,’ it was called. Does thee know it?”

Young Bill shook his head. “Mister, are you really a gunslinger? Say true?”

“I am.”

“Can I hold one of your guns for a minute?”

“Never in life,” I said, “but you can look at one of these, if you’d like.” I took a shell from my belt and handed it to him.

He examined it closely, from brass base to lead tip. “Gods, it’s heavy! Long, too! I bet if you shot someone with one of these, he’d stay down.”

“Yes. A shell’s a dangerous thing. But it can be pretty, too. Would you like to see a trick I can do with this one?”

“Sure.”

I took it back and began to dance it from knuckle to knuckle, my fingers rising and falling in waves. Young Bill watched, wide-eyed. “How does thee do it?”

“The same way anyone does anything,” I said. “Practice.”

“Will you show me the trick?”

“If you watch close, you may see it for yourself,” I said. “Here it is . . . and here it isn’t.” I palmed the shell so fast it disappeared, thinking of Susan Delgado, as I supposed I always would when I did this trick. “Now here it is again.”

The shell danced fast . . . then slow . . . then fast again.

“Follow it with your eyes, Bill, and see if you can make out how I get it to disappear. Don’t take your eyes off it.” I dropped my voice to a lulling murmur. “Watch . . . and watch . . . and watch. Does it make you sleepy?”

“A little,” he said. His eyes slipped slowly closed, then the lids rose again. “I didn’t sleep much last night.”

“Did you not? Watch it go. Watch it slow. See it disappear and then . . . see it as it speeds up again.”

Back and forth the shell went. The wind blew, as lulling to me as my voice was to him.

“Sleep if you want, Bill. Listen to the wind and sleep. But listen to my voice, too.”

“I hear you, gunslinger.” His eyes closed again and this time didn’t reopen. His hands were clasped limply in his lap. “I hear you very well.”

“You can still see the shell, can’t you? Even with your eyes closed.”

“Yes . . . but it’s bigger now. It flashes like gold.”

“Do you say so?”

“Yes . . .”

“Go deeper, Bill, but hear my voice.”

“I hear.”

“I want you to turn your mind back to last night. Your mind and your eyes and your ears. Will you do that?”

A frown creased his brow. “I don’t want to.”

“It’s safe. All that’s happened, and besides, I’m with you.”

“You’re with me. And you have guns.”

“So I do. Nothing will happen to you as long as you can hear my voice, because we’re together. I’ll keep thee safe. Do you understand that?”

“Yes.”

“Your da’ told you to sleep out under the stars, didn’t he?”

“Aye. It was to be a warm night.”

“But that wasn’t the real reason, was it?”

“No. It was because of Elrod. Once he twirled the bunkhouse cat by her tail, and she never came back. Sometimes he pulls me around by my hair and sings ‘The Boy Who Loved Jenny.’ My da’ can’t stop him, because Elrod’s bigger. Also, he has a knife in his boot. He could cut with it. But he couldn’t cut the beast, could he?” His clasped hands twitched. “Elrod’s dead and I’m glad. I’m sorry about all the others . . . and my da’, I don’t know what I’ll do wi’out my da’ . . . but I’m glad about Elrod. He won’t tease me nummore. He won’t scare me nummore. I seen it, aye.”

So he did know more than the top of his mind had let him remember.

“Now you’re out on the graze.”

“On the graze.”

“Wrapped up in your blanket and shinnie.”

“Shaddie.”

“Your blanket and shaddie. You’re awake, maybe looking up at the stars, at Old Star and Old Mother—”

“No, no, asleep,” Bill said. “But the screams wake me up. The screams from the bunkhouse. And the sounds of fighting. Things are breaking. And something’s roaring.”

“What do you do, Bill?”

“I go down. I’m afraid to, but my da’ . . . my da’s in there. I look in the window at the far end. It’s greasepaper, but I can see through it well enough. More than I want to see. Because I see . . . I see . . . mister, can I wake up?”

“Not yet. Remember that I’m with you.”

“Have you drawn your guns, mister?” He was shivering.

“I have. To protect you. What do you see?”

“Blood. And a beast.”

“What kind, can you tell?”

“A bear. One so tall its head reaches the ceiling. It goes up the middle of the bunkhouse . . . between the cots, ye ken, and on its back legs . . . and it grabs the men . . . it grabs the men and pulls them to pieces with its great long claws.” Tears began to escape his closed lids and roll down his cheeks. “The last one was Elrod. He ran for the back door . . . where the woodpile is just outside, ye ken . . . and when he understood it would have him before he could open the door and dash out, he turned around to fight. He had his knife. He went to stab it. . . .”

Slowly, as if underwater, the boy’s right hand rose from his lap. It was curled into a fist. He made a stabbing motion with it.

“The bear grabbed his arm and tore it off his shoulder. Elrod screamed. He sounded like a horse I saw one time, after it stepped in a gompa hole and broke its leg. The thing . . . it hit Elrod in the face with ’is own arm. The blood flew. There was gristle that flapped and wound around the skin like strings. Elrod fell against the door and started to slide down. The bear grabbed him and lifted him up and bit into his neck and there was a sound . . . mister, it bit Elrod’s head right off his neck. I want to wake up now. Please.”

“Soon. What did you do then?”

“I ran. I meant to go to the big house, but sai Jefferson . . . he . . . he . . .”

“He what?”

“He shot at me! I don’t think he meant to. I think he just saw me out of the corner of his eye and thought . . . I heard the bullet go by me. Wishhh! That’s how close it was. So I ran for the corral instead. I went between the poles. While I was crossing, I heard two more shots. Then there was more screaming. I didn’t look to see, but I knew it was sai Jefferson screaming that time.”

This part we knew from the tracks and leavings: how the thing had come charging out of the bunkhouse, how it had grabbed away the four-shot pistol and bent the barrel, how it had unzipped the rancher’s guts and thrown him into the bunkhouse with his proddies. The shot Jefferson had thrown at Young Bill had saved the boy’s life. If not for that, he would have run straight to the big house and been slaughtered with the Jefferson womenfolk.

“You go into the old hostelry where we found you.”

“Aye, so I do. And hide under the tack. But then I hear it . . . coming.”

He had gone back to the now way of remembering, and his words came more slowly. They were broken by bursts of weeping. I knew it was hurting him, remembering terrible things always hurts, but I pressed on. I had to, for what happened in that abandoned hostelry was the important part, and Young Bill was the only one who had been there. Twice he tried to come back to the then way of remembering, the ago. This was a sign that he was trying to struggle free of his trance, so I took him deeper. In the end I got it all.

The terror he’d felt as the grunting, snuffling thing approached. The way the sounds had changed, blurring into the snarls of a cat. Once it had roared, Young Bill said, and when he heard that sound, he’d let loose water in his trousers. He hadn’t been able to hold it. He waited for the cat to come in, knowing it would scent him where he lay—from the urine—only the cat didn’t. There was silence . . . silence . . . and then more screaming.

“At first it’s the cat screaming, then it changes into a human screaming. High to begin with, it’s like a woman, but then it starts to go down until it’s a man. It screams and screams. It makes me want to scream. I thought—”

“Think,” I said. “You think, Bill, because it’s happening now. Only I’m here to protect you. My guns are drawn.”

“I think my head will split open. Then it stops . . . and it comes in.”

“It walks up the middle to the other door, doesn’t it?”

He shook his head. “Not walks. Shuffles. Staggers. Like it’s hurt. It goes right past me. He. Now it’s he. He almost falls down, but grabs one of the stall doors and stays up. Then he goes on. He goes on a little better now.”

“Stronger?”

“Aye.”

“Do you see his face?” I thought I already knew the answer to that.

“No, only his feet, through the tack. The moon’s up, and I see them very well.”

Perhaps so, but we wouldn’t be identifying the skin-man from his feet, I felt quite sure. I opened my mouth, ready to start bringing him up from his trance, when he spoke again.

“There’s a ring around one of his ankles.”

I leaned forward, as if he could see me . . . and if he was deep enough, mayhap he could, even with his eyes closed. “What kind of ring? Was it metal, like a manacle?”

“I don’t know what that is.”

“Like a bridle-ring? You know, a hoss-clinkum?”

“No, no. Like on Elrod’s arm, but that’s a picture of a nekkid woman, and you can hardly make it out nummore.”

“Bill, are you talking about a tattoo?”

In his trance, the boy smiled. “Aye, that’s the word. But this one wasn’t a picture, just a blue ring around his ankle. A blue ring in his skin.”

I thought, We have you. You don’t know it yet, sai skin-man, but we have you.

“Mister, can I wake up now? I want to wake up.”

“Is there anything else?”

“The white mark?” He seemed to be asking himself.

“What white mark?”

He shook his head slowly from side to side, and I decided to let it go. He’d had enough.

“Come to the sound of my voice. As you come, you’ll leave everything that happened last night behind, because it’s over. Come, Bill. Come now.”

“I’m coming.” His eyes rolled back and forth behind his closed lids.

“You’re safe. Everything that happened at the ranch is ago. Isn’t it?”

“Yes . . .”

“Where are we?”

“On Debaria high road. We’re going to town. I ain’t been there but once. My da’ bought me candy.”

“I’ll buy you some, too,” I said, “for you’ve done well, Young Bill of the Jefferson. Now open your eyes.”

He did, but at first he only looked through me. Then his eyes cleared and he gave an uncertain smile. “I fell asleep.”

“You did. And now we should push for town before the wind grows too strong. Can you do that, Bill?”

“Aye,” he said, and as he got up he added, “I was dreaming of candy.”

* * *

The two not-so-good deputies were in the sheriff’s office when we got there, one of them—a fat fellow wearing a tall black hat with a gaudy rattlesnake band—taking his ease behind Peavy’s desk. He eyed the guns I was wearing and got up in a hurry.

“You’re the gunslinger, ain’tcha?” he said. “Well-met, well-met, we both say so. Where’s t’other one?”

I escorted Young Bill through the archway and into the jail without answering. The boy looked at the cells with interest but no fear. The drunk, Salty Sam, was long gone, but his aroma lingered.

From behind me, the other deputy asked, “What do you think you’re doing, young sai?”

“My business,” I said. “Go back to the office and bring me the keyring to these cells. And be quick about it, if you please.”

None of the smaller cells had mattresses on their bunks, so I took Young Bill to the drunk-and-disorderly cell where Jamie and I had slept the night before. As I put the two straw pallets together to give the boy a little more comfort—after what he’d been through, I reckoned he deserved all the comfort he could get—Bill looked at the chalked map on the wall.

“What is it, sai?”

“Nothing to concern you,” I said. “Now listen to me. I’m going to lock you in, but you’re not to be afraid, for you’ve done nothing wrong. ’Tis but for your own safety. I have an errand that needs running, and when it’s done, I’m going to come in there with you.”

“And lock us both in,” said he. “You’d better lock us both in. In case it comes back.”

“Do you remember it now?”

“A little,” said he, looking down. “It wasn’t a man . . . then it was. It killed my da’.” He put the heels of his hands against his eyes. “Poor Da’.”

The deputy with the black hat returned with the keys. The other was right behind him. Both were gawking at the boy as if he were a two-headed goat in a roadshow.

I took the keys. “Good. Now back to the office, both of you.”

“Seems like you might be throwing your weight around a little, youngster,” Black Hat said, and the other—a little man with an undershot jaw—nodded vigorously.

“Go now,” I said. “This boy needs rest.”

They looked me up and down, then went. Which was the correct thing. The only thing, really. My mood was not good.

The boy kept his eyes covered until their bootheels faded back through the arch, then he lowered his hands. “Will you catch him, sai?”

“Yes.”

“And will you kill him?”

“Does thee want me to kill him?”

He considered this, and nodded. “Aye. For what he did to my da’, and to sai Jefferson, and all the others. Even Elrod.”

I closed the door of the cell, found the right key, and turned it. The keyring I hung over my wrist, for it was too big for my pocket. “I’ll make you a promise, Young Bill,” I said. “One I swear to on my father’s name. I won’t kill him, but you shall be there when he swings, and with my own hand I’ll give you the bread to scatter beneath his dead feet.”

* * *

In the office, the two not-so-good deputies eyed me with caution and dislike. That was nothing to me. I hung the keyring on the peg next to the jing-jang and said, “I’ll be back in an hour, maybe a little less. In the meantime, no one goes into the jail. And that includes you two.”

“High-handed for a shaveling,” the one with the undershot jaw remarked.

“Don’t fail me in this,” I said. “It wouldn’t be wise. Do you understand?”

Black Hat nodded. “But the sheriff will hear how you done with us.”

“Then you’ll want to have a mouth still capable of speech when he gets back,” I said, and went out.

* * *

The wind had continued to strengthen, blowing clouds of gritty, salt-flavored dust between the false-fronted buildings. I had Debaria high street entirely to myself except for a few hitched horses that stood with their hindquarters turned to the wind and their heads unhappily lowered. I would not leave my own so—nor Millie, the mule the boy had ridden—and led them down to the livery stable at the far end of the street. There the hostler was glad to take them, especially when I split him off half a gold knuck from the bundle I carried in my vest.

No, he said in answer to my first question, there was no jeweler in Debaria, nor ever had been in his time. But the answer to my second question was yar, and he pointed across the street to the blacksmith’s shop. The smith himself was standing in the doorway, the hem of his tool-filled leather apron flapping in the wind. I walked across and he put his fist to his forehead. “Hile.”

I hiled him in return and told him what I wanted—what Vannay had said I might need. He listened closely, then took the shell I handed him. It was the very one I’d used to entrance Young Bill. The blackie held it up to the light. “How many grains of powder does it blow, can’ee say?”

Of course I could. “Fifty-seven.”

“As many as that? Gods! It’s a wonder the barrel of your revolver don’t bust when’ee pull the trigger!”

The shells in my father’s guns—the ones I might someday carry—blew seventy-six, but I didn’t say so. He’d likely not have believed it. “Can you do what I ask, sai?”

“I think so.” He considered, then nodded. “Aye. But not today. I don’t like to run my smithhold hot in the wind. One loose ember and the whole town might catch ablaze. We’ve had no fire department since my da’ was a boy.”

I took out my bag of gold knuckles and shook two into the palm of my hand. I considered, then added a third. The smith stared at them with wonder. He was looking at two years’ wages.

“It has to be today,” I said.

He grinned, showing teeth of amazing whiteness within the forest of his ginger beard. “Tempting devil, get not aside! For what you’re showin me, I’d risk burning Gilead herself to her foundations. You’ll have it by sundown.”

“I’ll have it by three.”

“Aye, three’s what I meant. To the shaved point of the minute.”

“Good. Now tell me, which restaurant cooks the best chow in town?”

“There’s only two, and neither of em’ll make you remember your mother’s bird puddin, but neither’ll poison’ee. Racey’s Café is probably the better.”

That was good enough for me; I thought a growing boy like Bill Streeter would take quantity over quality any day. I headed for the café, now working against the wind. It’ll be a full-going simoom by dark, the boy had told me, and I thought he was right. He had been through a lot, and needed time to rest. Now that I knew about the ankle tattoo, I might not need him at all . . . but the skin-man wouldn’t know that. And in the jail, Young Bill was safe. At least I hoped so.

* * *

It was stew, and I could have sworn it had been seasoned with alkali grit instead of salt, but the kid ate all of his and finished mine as well when I put it aside. One of the not-so-good deputies had made coffee, and we drank that from tin cups. We made our meal right there in the cell, sitting cross-legged on the floor. I listened for the jing-jang, but it stayed quiet. I wasn’t surprised. Even if Jamie and the High Sheriff came near one at their end, the wind had probably taken the wires down.

“I guess you know all about these storms you call simooms,” I said to Young Bill.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “This is the season for em. The proddies hate em and the pokies hate em even more, because if they’re out on the range, they have to sleep rough. And they can’t have a fire at night, accourse, because of—”

“Because of the embers,” I said, remembering the blacksmith.

“Just as you say. Stew all gone, is it?”

“So it is, but there’s one more thing.”

I handed over a little sack. He looked inside it and lit up. “Candy! Rollers and chocker-twists!” He extended the bag. “Here, you have the first.”

I took one of the little chocolate twists, then pushed the bag back to him. “You have the rest. If it won’t make your belly sick, that is.”

“It won’t!” And he dived in. It did me good to see him. After the third roller went into his gob, he cheeked it—which made him look like a squirrel with a nut—and said, “What’ll happen to me, sai? Now that my da’s gone?”

“I don’t know, but there’ll be water if God wills it.” I already had an idea where that water might be. If we could put paid to the skin-man, a certain large lady named Everlynne would owe us a good turn, and I doubt if Bill Streeter would be the first stray she’d taken in.

I returned to the subject of the simoom. “How much will it strengthen?”

“It’ll blow a gale tonight. Probably after midnight. And by noon tomorrow, it’ll be gone.”

“Does thee know where the salties live?”

“Aye, I’ve even been there. Once with my da’, to see the races they sometimes have up there, and once with some proddies looking for strays. The salties take em in, and we pay with hard biscuit for the ones that have the Jefferson brand.”

“My trailmate’s gone there with Sheriff Peavy and a couple of others. Think they have any chance of getting back before nightfall?”

I felt sure he would say no, but he surprised me. “Being as it’s all downhill from Salt Village—which is on this side of Little Debaria—I’d say they could. If they rode hard.”

That made me glad I’d told the blacksmith to hurry, although I knew better than to trust the reckoning of a mere boy.

“Listen to me, Young Bill. When they come back, I expect they’ll have some of the salties with em. Maybe a dozen, maybe as many as twenty. Jamie and I may have to walk em through the jail for you to look at, but you needn’t be afraid, because the door of this cell will be locked. And you don’t have to say anything, just look.”

“If you’re thinking I can tell which one killed my da’, I can’t. I don’t even remember if I saw him.”

“You probably won’t have to see them at all,” I said. This I truly believed. We’d have them into the sheriff’s office by threes, and have them hike their pants. When we found the one with the blue ring tattooed around his ankle, we’d have our man. Not that he was a man. Not anymore. Not really.

“Wouldn’t you like another chocker, sai? There’s three left, and I can’t eat nummore.”

“Save them for later,” I said, and got up.

His face clouded. “Will you come back? I don’t want to be in here on my own.”

“Aye, I’ll come back.” I stepped out, locked the cell door, then tossed the keys to him through the bars. “Let me in when I do.”

* * *

The fat deputy with the black hat was Strother. The one with the undershot jaw was Pickens. They looked at me with care and mistrust, which I thought a good combination, coming from the likes of them. I could work with care and mistrust.

“If I asked you fellows about a man with a blue ring tattooed on his ankle, would it mean anything to you?”

They exchanged a glance and then Black Hat—Strother—said, “The stockade.”

“What stockade would that be?” Already I didn’t like the sound of it.

“Beelie Stockade,” Pickens said, looking at me as if I were the utterest of utter idiots. “Does thee not know of it? And thee a gunslinger?”

“Beelie Town’s west of here, isn’t it?” I asked.

“Was,” Strother said. “It’s Beelie Ghost Town now. Harriers tore through it five year ago. Some say John Farson’s men, but I don’t believe that. Never in life. ’Twas plain old garden-variety outlaws. Once there was a militia outpost—back in the days when there was a militia—and Beelie Stockade was their place o’ business. It was where the circuit judge sent thieves and murderers and card cheats.”

“Witches n warlocks, too,” Pickens volunteered. He wore the face of a man remembering the good old days, when the railroad trains ran on time and the jing-jang no doubt rang more often, with calls from more places. “Practicers of the dark arts.”

“Once they took a cannibal,” Strother said. “He ate his wife.” This caused him to give out with a foolish giggle, although whether it was the eating or the relationship that struck him funny I couldn’t say.

“He was hung, that fellow,” Pickens said. He bit off a chunk of chew and worked it with his peculiar jaw. He still looked like a man remembering a better, rosier past. “There was lots of hangings at Beelie Stockade in those days. I went several times wi’ my da’ and my marmar to see em. Marmar allus packed a lunch.” He nodded slowly and thoughtfully. “Aye, many and many-a. Lots o’ folks came. There was booths and clever people doing clever things such as juggling. Sometimes there was dogfights in a pit, but accourse it was the hangins that was the real show.” He chuckled. “I remember this one fella who kicked a regular commala when the drop didn’t break ’is—”

“What’s this to do with blue ankle tattoos?”

“Oh,” Strother said, recalled to the initial subject. “Anyone who ever did time in Beelie had one of those put on, y’see. Although I disremember if it was for punishment or just identification in case they ran off from one o’ the work gangs. All that stopped ten year ago, when the stockade closed. That’s why the harriers was able to have their way with the town, you know—because the militia left and the stockade closed. Now we have to deal with all the bad element and riffraff ourselves.” He eyed me up and down in the most insolent way. “We don’t get much help from Gilead these days. Nawp. Apt to get more from John Farson, and there’s some that’d send a parlay-party west to ask him.” Perhaps he saw something in my eyes, because he sat up a little straighter in his chair and said, “Not me, accourse. Never. I believe in the straight law and the Line of Eld.”

“So do we all,” Pickens said, nodding vigorously.

“Would you want to guess if some of the salt-miners did time in Beelie Stockade before it was decommissioned?” I asked.

Strother appeared to consider, then said: “Oh, probably a few. Nummore’n four in every ten, I should say.”

In later years I learned to control my face, but those were early times, and he must have seen my dismay. It made him smile. I doubt if he knew how close that smile brought him to suffering. I’d had a difficult two days, and the boy weighed heavily on my mind.

“Who did’ee think would take a job digging salt blocks out of a miserable hole in the ground for penny wages?” Strother asked. “Model citizens?”

It seemed that Young Bill would have to look at a few of the salties, after all. We’d just have to hope the fellow we wanted didn’t know the ring tattoo was the only part of him the kid had seen.

* * *

When I went back to the cell, Young Bill was lying on the pallets, and I thought he’d gone to sleep, but at the sound of my bootheels he sat up. His eyes were red, his cheeks wet. Not sleeping, then, but mourning. I let myself in, sat down beside him, and put an arm around his shoulders. This didn’t come naturally to me—I know what comfort and sympathy are, but I’ve never been much good at giving such. I knew what it was to lose a parent, though. Young Bill and Young Roland had that much in common.

“Did you finish your candy?” I asked.

“Don’t want the rest,” he said, and sighed.

Outside the wind boomed hard enough to shake the building, then subsided.

“I hate that sound,” he said—just what Jamie DeCurry had said. It made me smile a little. “And I hate being in here. It’s like I did something wrong.”

“You didn’t,” I said.

“Maybe not, but it already seems like I’ve been here forever. Cooped up. And if they don’t get back before nightfall, I’ll have to stay longer. Won’t I?”

“I’ll keep you company,” I said. “If those deputies have a deck of cards, we can play Jacks Pop Up.”

“For babies,” said he, morosely.

“Then Watch Me or poker. Can thee play those?”

He shook his head, then brushed at his cheeks. The tears were flowing again.

“I’ll teach thee. We’ll play for matchsticks.”

“I’d rather hear the story you talked about when we stopped in the sheppie’s lay-by. I don’t remember the name.”

“‘The Wind Through the Keyhole,’” I said. “But it’s a long one, Bill.”

“We have time, don’t we?”

I couldn’t argue that. “There are scary bits in it, too. Those things are all right for a boy such as I was—sitting up in his bed with his mother beside him—but after what you’ve been through . . .”

“Don’t care,” he said. “Stories take a person away. If they’re good ones, that is. It is a good one?”

“Yes. I always thought so, anyway.”

“Then tell it.” He smiled a little. “I’ll even let you have two of the last three chockers.”

“Those are yours, but I might roll a smoke.” I thought about how to begin. “Do you know stories that start, ‘Once upon a bye, before your grandfather’s grandfather was born’?”

“They all start that way. At least, the ones my da’ told me. Before he said I was too old for stories.”

“A person’s never too old for stories, Bill. Man and boy, girl and woman, never too old. We live for them.”

“Do you say so?”

“I do.”

I took out my tobacco and papers. I rolled slowly, for in those days it was a skill yet new to me. When I had a smoke just to my liking—one with the draw end tapered to a pinhole—I struck a match on the wall. Bill sat cross-legged on the straw pallets. He took one of the chockers, rolled it between his fingers much as I’d rolled my smoke, then tucked it into his cheek.

I started slowly and awkwardly, because storytelling was another thing that didn’t come naturally to me in those days . . . although it was a thing I learned to do well in time. I had to. All gunslingers have to. And as I went along, I began to speak more naturally and easily. Because I began hearing my mother’s voice. It began to speak through my own mouth: every rise, dip, and pause.

I could see him fall into the tale, and that pleased me—it was like hypnotizing him again, but in a better way. A more honest way. The best part, though, was hearing my mother’s voice. It was like having her again, coming out from far inside me. It hurt, of course, but more often than not the best things do, I’ve found. You wouldn’t think it could be so, but—as the oldtimers used to say—the world’s tilted, and there’s an end to it.

“Once upon a bye, before your grandfather’s grandfather was born, on the edge of an unexplored wilderness called the Endless Forest, there lived a boy named Tim with his mother, Nell, and his father, Big Ross. For a time, the three of them lived happily enough, although they owned little. . . .”