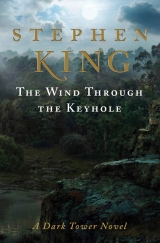

Текст книги "The Wind Through the Keyhole"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

She lifted her skirts to her knee, and we saw a butcher’s knife in a rawhide scabbard strapped to the outside of her calf.

“So let it come for Everlynne, daughter of Roseanna.”

“You said you saw something else,” I said.

She considered me with her bright black eyes, then turned to the women. “Clemmie, Brianna, serve out. Fortuna, you will say grace, and be sure to ask God forgiveness for your blasphemy and thank Him that your heart still beats.”

Everlynne grasped me above the elbow, drew me through the gate, and walked me to the well where the unfortunate Fortuna had been attacked. There we were alone.

“I saw its prick,” she said in a low voice. “Long and curved like a scimitar, twitching and full of the black stuff that serves it for blood . . . serves it for blood in that shape, any-ro’. It meant to kill her as it had Dolores, aye, right enough, but it meant to fuck her, too. It meant to fuck her as she died.”

* * *

Jamie and I ate with them—Fortuna even ate a little—and then we mounted up for town. But before we left, Everlynne stood by my horse and spoke to me again.

“When your business here is done, come and see me again. I have something for you.”

“What might that be, sai?”

She shook her head. “Now is not the time. But when the filthy thing is dead, come here.” She took my hand, raised it to her lips, and kissed it. “I know who you are, for does your mother not live in your face? Come to me, Roland, son of Gabrielle. Fail not.”

Then she stepped away before I could say another word, and glided in through the gate.

* * *

The Debaria high street was wide and paved, although the pavement was crumbling away to the hardpan beneath in many places and would be entirely gone before too many years passed. There was a good deal of commerce, and judging from the sound coming from the saloons, they were doing a fine business. We only saw a few horses and mules tied to the hitching-posts, though; in that part of the world, livestock was for trading and eating, not for riding.

A woman coming out of the mercantile with a basket over her arm saw us and stared. She ran back in, and several more people came out. By the time we reached the High Sheriff’s office—a little wooden building attached to the much larger stone-built town jail—the streets were lined with spectators on both sides.

“Have ye come to kill the skin-man?” the lady with the basket called.

“Those two don’t look old enough to kill a bottle of rye,” a man standing in front of the Cheery Fellows Saloon & Café called back. There was general laughter and murmurs of agreement at this sally.

“Town looks busy enough now,” Jamie said, dismounting and looking back at the forty or fifty men and women who’d come away from their business (and their pleasure) to have a gleep at us.

“It’ll be different after sundown,” I said. “That’s when such creatures as this skin-man do their marauding. Or so Vannay says.”

We went into the office. Hugh Peavy was a big-bellied man with long white hair and a droopy mustache. His face was deeply lined and careworn. He saw our guns and looked relieved. He noted our beardless faces and looked less so. He wiped off the nib of the pen he had been writing with, stood up, and held out his hand. No forehead-knocking for this fellow.

After we’d shaken with him and introduced ourselves, he said: “I don’t mean to belittle you, young fellows, but I was hoping to see Steven Deschain himself. And perhaps Peter McVries.”

“McVries died three years ago,” I said.

Peavy looked shocked. “Do you say so? For he was a trig hand with a gun. Very trig.”

“He died of a fever.” Very likely induced by poison, but this was nothing the High Sheriff of the Debaria Outers needed to know. “As for Steven, he’s otherwise occupied, and so he sent me. I am his son.”

“Yar, yar, I’ve heard your name and a bit of your exploits in Mejis, for we get some news even out here. There’s the dit-dah wire, and even a jing-jang.” He pointed to a contraption on the wall. Written on the brick beneath it was a sign reading DO NOT TOUCH WITHOUT PERMIZION. “It used to go all the way to Gilead, but these days only to Sallywood in the south, the Jefferson spread to the north, and the village in the foothills—Little Debaria, it’s called. We even have a few streetlamps that still work—not gas or kerosene but real sparklights, don’tcha see. Townfolk think such’ll keep the creature away.” He sighed. “I am less confident. This is a bad business, young fellows. Sometimes I feel the world has come loose of its moorings.”

“It has,” I said. “But what comes loose can be tied tight again, Sheriff.”

“If you say so.” He cleared his throat. “Now, don’t take this as disrespect, I know ye are who ye say ye are, but I was promised a sigul. If you’ve brought it, I’d have it, for it means special to me.”

I opened my swag-bag and brought out what I’d been given: a small wooden box with my father’s mark—the D with the S inside of it—stamped on the hinged lid. Peavy took it with the smallest of smiles dimpling the corners of his mouth beneath his mustache. To me it looked like a remembering smile, and it took years off his face.

“Do’ee know what’s inside?”

“No.” I had not been asked to look.

Peavy opened the box, looked within, then returned his gaze to Jamie and me. “Once, when I was still only a deputy, Steven Deschain led me, and the High Sheriff that was, and a posse of seven against the Crow Gang. Has your father ever spoken to you of the Crows?”

I shook my head.

“Not skin-men, no, but a nasty lot of work, all the same. They robbed what there was to rob, not just in Debaria but all along the ranchlands out this way. Trains, too, if they got word one was worth stopping. But their main business was kidnapping for ransom. A coward’s crime, sure—I’m told Farson favors it—but it paid well.

“Your da’ showed up in town only a day after they stole a rancher’s wife—Belinda Doolin. Her husband called on the jing-jang as soon as they left and he was able to get himself untied. The Crows didn’t know about the jing-jang, and that was their undoing. Accourse it helped that there was a gunslinger doing his rounds in this part of the world; in those days, they had a knack of turning up when and where they were needed.”

He eyed us. “P’raps they still do. Any-ro’, we got out t’ranch while the crime was still fresh. There were places where any of us would have lost the trail—it’s mostly hardpan out north of here, don’tcha see—but your father had eyes like you wouldn’t believe. Hawks ain’t even in it, dear, or eagles, either.”

I knew of my father’s sharp eyes and gift for trailing. I also knew that this story probably had nothing to do with our business, and I should have told him to move along. But my father never talked about his younger days, and I wanted to hear this tale. I was hungry to hear it. And it turned out to have a little more to do with our business in Debaria than I at first thought.

“The trail led in the direction of the mines—what Debaria folk call the salt-houses. The workings had been abandoned in those days; it was before the new plug was found twenty year ago.”

“Plug?” Jamie asked.

“Deposit,” I said. “He means a fresh deposit.”

“Aye, as you say. But all that were abandoned then, and made a fine hideout for such as those beastly Crows. Once the trail left the flats, it went through a place of high rocks before coming out on the Low Pure, which is to say the foothill meadows below the salt-houses. The Low is where a sheepherder was killed just recent, by something that looked like a—”

“Like a wolf,” I said. “This we know. Go on.”

“Well-informed, are ye? Well, that’s all to the good. Where was I, now? Ah, I know—those rocks that are now known in these parts as Ambush Arroyo. It’s not an arroyo, but I suppose people like the sound. That’s where the tracks went, but Deschain wanted to go around and come in from the east. From the High Pure. The sheriff, Pea Anderson it was back then, didn’t want none o’ that. Eager as a bird with its eye on a worm he was, mad to press on. Said it would take em three days, and by then the woman might be dead and the Crows anywhere. He said he was going the straight way, and he’d go alone if no one wanted to go with him. ‘Or unless you order me in the name of Gilead to do different,’ he says to your da’.

“‘Never think it,’ Deschain says, ‘for Debaria is your fill; I have my own.’

“The posse went. I stayed with your da’, lad. Sheriff Anderson turned to me in the saddle and said, ‘I hope they’re hiring at one of the ranches, Hughie, because your days of wearing tin on your vest are over. I’m done with’ee.’

“Those were the last words he ever said to me. They rode off. Steven of Gilead squatted on his hunkers and I hunkered with him. After half an hour of quiet—might have been longer—I says to him, ‘I thought we were going to hook around . . . unless you’re done with me, too.’

“‘No,’ he says. ‘Your hire is not my business, Deputy.’

“‘Then what are we waitin for?’

“‘Gunfire,’ says he, and not five minutes later we heard it. Gunfire and screams. It didn’t last long. The Crows had seen us coming—probably nummore’n a glint of sun on a bootcap or bit o’ saddle brightwork was enough to attract their attention, for Pa Crow was powerful trig—and doubled back. They got up in those high rocks and poured down lead on Anderson and his possemen. There were more guns in those days, and the Crows had a good share. Even a speed-shooter or two.

“So we went around, all right? Took us only two days, because Steven Deschain pushed hard. On the third day, we camped downslope and rose before dawn. Now, if ye don’t know, and no reason ye should, salt-houses are just caverns in the cliff faces up there. Whole families lived in em, not just the miners themselves. The tunnels go down into the earth from the backs of em. But as I say, in those days all were deserted. Yet we saw smoke coming from the vent on top of one, and that was as good as a kinkman standing out in front of a carnival tent and pointing at the show inside, don’tcha see it.

“‘This is the time,’ Steven says, ‘because they will have spent the last nights, once they were sure they were safe, deep in drink. They’ll still be sleeping it off. Will you stand with me?’

“‘Aye, gunslinger, that I will,’ I tells him.”

When Peavy said this, he unconsciously straightened his back. He looked younger.

“We snuck the last fifty or sixty yards, yer da’ with his gun drawn in case they’d posted a guard. They had, but he was only a lad, and fast asleep. The Deschain holstered his gun, swotted him with a rock, and laid him out. I later saw that young fellow standing on a trapdoor with tears running out of his eyes, a mess in his pants, and a rope around his neck. He wasn’t but fourteen, yet he’d taken his turn at sai Doolin—the kidnapped woman, don’tcha know, and old enough to be his grandmother—just like the rest of them, and I shed no tears when the rope shut off his cries for mercy. The salt ye take is the salt ye must pay for, as anyone from these parts will tell you.

“The gunslinger crep’ inside, and I right after him. They was all lying around, snoring like dogs. Hell, boys, they were dogs. Belinda Doolin was tied to a post. She saw us, and her eyes widened. Steven Deschain pointed to her, then to himself, then cupped his hands together, then pointed to her again. You’re safe, he meant. I never forgot the look of gratitude in her face as she nodded to him that she understood. You’re safe—that’s the world we grew up in, young men, the one that’s almost gone now.

“Then the Deschain says, ‘Wake up, Allan Crow, unless you’d go into the clearing at the end of the path with your eyes shut. Wake up, all.’

“They did. He never meant to try and bring them all in alive—’twould have been madness, that I’m sure you must see—but he wouldn’t shoot them as they slept, either. They woke up to varying degrees, but not for long. Steven drew his guns so fast I never saw his hands move. Lightning ain’t in it, dear. At one moment those revolvers with their big sandalwood grips were by his sides; at the next he was blazing away, the noise like thunder in that closed-in space. But that didn’t keep me from drawing my own gun. It was just an old barrel-shooter I had from my granda’, but I put two of them down with it. The first two men I ever killed. There have been plenty since, sad to say.

“The only one who survived that first fusillade was Pa Crow himself—Allan Crow. He was an old man, all snarled up and frozen on one side of his face from a stroke or summat, but he moved fast as the devil just the same. He was in his longjohns, and his gun was stuck in the top of one of his boots there at the end of his bedroll. He grabbed it up and turned toward us. Steven shot him, but the old bastard got off a single round. It went wild, but . . .”

Peavy, who could have been no older in those days than we two young men standing before him, opened the box on its cunning hinges, mused a moment at what he saw inside, then looked up at me. That little remembering smile still touched the corners of his mouth. “Have you ever seen a scar on your father’s arm, Roland? Right here?” He touched the place just above the crook of his elbow, where a man’s yanks begin.

My father’s body was a map of scars, but it was a map I knew well. The scar above his inner elbow was a deep dimple, almost like the ones not quite hidden by Sheriff Peavy’s mustache when he smiled.

“Pa Crow’s last shot hit the wall above the post where the woman was tied, and richocheted.” He turned the box and held it out to me. Inside was a smashed slug, a big one, a hard caliber. “I dug this out of your da’s arm with my skinning knife, and gave it to him. He thanked me, and said someday I should have it back. And here it is. Ka is a wheel, sai Deschain.”

“Have you ever told this story?” I asked. “For I have never heard it.”

“That I dug a bullet from the flesh of Arthur’s true descendant? Eld of the Eld? No, never until now. For who would believe it?”

“I do,” I said, “and I thank you. It could have poisoned him.”

“Nar, nar,” Peavy said with a chuckle. “Not him. The blood of Eld’s too strong. And if I’d been laid low . . . or too squeamy . . . he would have done it himself. As it was, he let me take most of the credit for the Crow Gang, and I’ve been sheriff ever since. But not much longer. This skin-man business has done for me. I’ve seen enough blood, and have no taste for mysteries.”

“Who’ll take your place?” I asked.

He seemed surprised by the question. “Probably nobody. The mines will play out again in a few years, this time for good, and such rail lines as there are won’t last much longer. The two things together will finish Debaria, which was once a fine little city in the time of yer grandfathers. That holy hencoop I’m sure ye passed on the way in may go on; nothing else.”

Jamie looked troubled. “But in the meantime?”

“Let the ranchers, drifters, whoremasters, and gamblers all go to hell in their own way. It’s none o’ mine, at least for much longer. But I’ll not leave until this business is settled, one way or another.”

I said, “The skin-man was at one of the women at Serenity. She’s badly disfigured.”

“Been there, have ye?”

“The women are terrified.” I thought this over, and remembered a knife strapped to a calf as thick as the trunk of a young birch. “Except for the prioress, that is.”

He chuckled. “Everlynne. That one’d spit in the devil’s face. And if he took her down to Nis, she’d be running the place in a month.”

I said, “Do you have any idea who this skin-man might be when he’s in his human shape? If you do, tell us, I beg. For, as my father told your Sheriff Anderson that was, this is not our fill.”

“I can’t give ye a name, if that’s what you mean, but I might be able to give ye something. Follow me.”

* * *

He led us through the archway behind his desk and into the jail, which was in the shape of a T. I counted eight big cells down the central aisle and a dozen small ones on the cross-corridor. All were empty except for one of the smaller ones, where a drunk was snoozing away the late afternoon on a straw pallet. The door to his cell stood open.

“Once all of these cells would have been filled on Efday and Ethday,” Peavy said. “Loaded up with drunk cowpunchers and farmhands, don’tcha see it. Now most people stay in at night. Even on Efday and Ethday. Cowpokes in their bunkhouses, farmhands in theirs. No one wants to be staggering home drunk and meet the skin-man.”

“The salt-miners?” Jamie asked. “Do you pen them, too?”

“Not often, for they have their own saloons up in Little Debaria. Two of em. Nasty places. When the whores down here at the Cheery Fellows or the Busted Luck or the Bider-Wee get too old or too diseased to attract custom, they end up in Little Debaria. Once they’re drunk on White Blind, the salties don’t much care if a whore has a nose as long as she still has her sugar-purse.”

“Nice,” Jamie muttered.

Peavy opened one of the large cells. “Come on in here, boys. I haven’t any paper, but I do have some chalk, and here’s a nice smooth wall. It’s private, too, as long as old Salty Sam down there doesn’t wake up. And he rarely does until sundown.”

From the pocket of his twill pants the sheriff took a goodish stick of chalk, and on the wall he drew a kind of long box with jags all across the top. They looked like a row of upside-down V ’s.

“Here’s the whole of Debaria,” Peavy said. “Over here’s the rail line you came in on.” He drew a series of hashmarks, and as he did so I remembered the enjie and the old fellow who’d served as our butler.

“Sma’ Toot is off the rails,” I said. “Can you put together a party of men to set it right? We have money to pay for their labor, and Jamie and I would be happy to work with them.”

“Not today,” Peavy said absently. He was studying his map. “Enjie still out there, is he?”

“Yes. Him and another.”

“I’ll send Kellin and Vikka Frye out in a bucka. Kellin’s my best deputy—the other two ain’t worth much—and Vikka’s his son. They’ll pick em up and bring em back in before dark. There’s time, because the days is long this time o’ year. For now, just pay attention, boys. Here’s the tracks and here’s Serenity, where that poor girl you spoke to was mauled. On the High Road, don’tcha see it.” He drew a little box for Serenity, and put an X in it. North of the women’s retreat, up toward the jags at the top of his map, he put another X. “This is where Yon Curry, the sheepherder, was killed.”

To the left of this X, but pretty much on the same level—which is to say, below the jags—he put another.

“The Alora farm. Seven killed.”

Farther yet to the left and little higher, he chalked another X.

“Here’s the Timbersmith farm on the High Pure. Nine killed. It’s where we found the little boy’s head on a pole. Tracks all around it.”

“Wolf?” I asked.

He shook his head. “Nar, some kind o’ big cat. At first. Before we lost the trail, they changed into what looked like hooves. Then . . .” He looked at us grimly. “Footprints. First big—like a giant’s, almost—but then smaller and smaller until they were the size of any man’s tracks. Any-ro’, we lost em in the hardpan. Mayhap your father wouldn’t’ve, sai.”

He went on marking the map, and when he was done, stepped away so we could see it clearly.

“Such as you are supposed to have good brains as well as fast hands, I was always told. So what do you make of this?”

Jamie stepped forward between the rows of pallets (for this cell must have been for many guests, probably brought in on drunk-and-disorderly), and traced the tip of his finger over the jags at the top of the map, blurring them a little. “Do the salt-houses run all along here? In all the foothills?”

“Yar. The Salt Rocks, those hills’re called.”

“Little Debaria is where?”

Peavy made another box for the salt-miners’ town. It was close to the X he’d made to mark the place where the woman and the gambler had been killed . . . for it was Little Debaria they’d been headed for.

Jamie studied the map a bit more, then nodded. “Looks to me like the skin-man could be one of the miners. Is that what you think?”

“Aye, a saltie, even though a couple of them has been torn up, too. It makes sense—as much as anything in a crazy business like this can make sense. The new plug’s a lot deeper than the old ones, and everyone knows there are demons in the earth. Mayhap one of the miners struck on one, wakened it, and was done a mischief by it.”

“There are also leftovers from the Great Old Ones in the ground,” I said. “Not all are dangerous, but some are. Perhaps one of those old things . . . those what-do-you-callums, Jamie?”

“Artyfax,” he said.

“Yes, those. Perhaps one of those is responsible. Mayhap the fellow will be able to tell us, if we take him alive.”

“Sma’ chance of that,” Peavy growled.

I thought there was a good chance. If we could identify him and close on him in the daytime, that was.

“How many of these salties are there?” I asked.

“Not s’many as in the old days, because now it’s just the one plug, don’tcha see it. I sh’d say no more’n . . . two hundred.”

I met Jamie’s eyes, and saw a glint of humor in them. “No fret, Roland,” said he. “I’m sure we can interview em all by Reaptide. If we hurry.”

He was exaggerating, but I still saw several weeks ahead of us in Debaria. We might interview the skin-man and still not be able to pick him out, either because he was a masterful liar or because he had no guilt to cover up; his day-self might truly not know what his night-self was doing. I wished for Cuthbert, who could look at things that seemed unrelated and spot the connections, and I wished for Alain, with his power to touch minds. But Jamie wasn’t so bad, either. He had, after all, seen what I should have seen myself, what was right in front of my nose. On one matter I was in complete accord with Sheriff Hugh Peavy: I hated mysteries. It’s a thing that has never changed in this long life of mine. I’m not good at solving them; my mind has never run that way.

When we trooped back into the office, I said, “I have some questions I must ask you, Sheriff. The first is, will you open to us, if we open to you? The second—”

“The second is do I see you for what you are and accept what you do. The third is do I seek aid and succor. Sheriff Peavy says yar, yar, and yar. Now for gods’ sake set your brains to working, fellows, for it’s over two weeks since this thing showed up at Serenity, and that time it didn’t get a full meal. Soon enough it’ll be out there again.”

“It only prowls at night,” Jamie said. “You’re sure of that much?”

“I am.”

“Does the moon have any effect on it?” I asked. “Because my father’s advisor—and our teacher that was—says that in some of the old legends . . .”

“I’ve heard the legends, sai, but in that they’re wrong. At least for this particular creatur’ they are. Sometimes the moon’s been full when it strikes—it was Full Peddler when it showed up at Serenity, all covered with scales and knobs like an alligator from the Long Salt Swamps—but it did its work at Timbersmith when the moon was dark. I’d like to tell you different, but I can’t. I’d also like to end this without having to pick anyone else’s guts out of the bushes or pluck some other kiddie’s head off’n a fencepost. Ye’ve been sent here to help, and I hope like hell you can . . . although I’ve got my doubts.”

* * *

When I asked Peavy if there was a good hotel or boardinghouse in Debaria, he chuckled.

“The last boardinghouse was the Widow Brailley’s. Two year ago, a drunk saddletramp tried to rape her in her own outhouse, as she sat at business. But she was always a trig one. She’d seen the look in his eye, and went in there with a knife under her apron. Cut his throat for him, she did. Stringy Bodean, who used to be our Justice Man before he decided to try his luck at raising horses in the Crescent, declared her not guilty by reason of self-defense in about five minutes, but the lady decided she’d had enough of Debaria and trained back to Gilead, where she yet bides, I’ve no doubt. Two days after she left, some drunken buffoon burned the place to the ground. The hotel still stands. It’s called the Delightful View. The view ain’t delightful, young fellows, and the beds is full of bugs as big as toads’ eyeballs. I wouldn’t sleep in one without putting on a full suit of Arthur Eld’s armor.”

And so we ended up spending our first night in Debaria in the large drunk-and-disorderly cell, beneath Peavy’s chalked map. Salty Sam had been set free, and we had the jail to ourselves. Outside, a strong wind had begun to blow off the alkali flats to the west of town. The moaning sound it made around the eaves caused me to think again of the story my mother used to read to me when I was just a sma’ toot myself—the story of Tim Stoutheart and the starkblast Tim had to face in the Great Woods north of New Canaan. Thinking of the boy alone in those woods has always chilled my heart, just as Tim’s bravery has always warmed it. The stories we hear in childhood are the ones we remember all our lives.

After one particularly strong gust—the Debaria wind was warm, not cold like the starkblast—struck the side of the jail and puffed alkali grit in through the barred window, Jamie spoke up. It was rare for him to start a conversation.

“I hate that sound, Roland. It’s apt to keep me awake all night.”

I loved it myself; the sound of the wind has always made me think of good times and far places. Although I confess I could have done without the grit.

“How are we supposed to find this thing, Jamie? I hope you have some idea, because I don’t.”

“We’ll have to talk to the salt-miners. That’s the place to start. Someone may have seen a fellow with blood on him creeping back to where the salties live. Creeping back naked. For he can’t come back clothed, unless he takes them off beforehand.”

That gave me a little hope. Although if the one we were looking for knew what he was, he might take his clothes off when he felt an attack coming on, hide them, then come back to them later. But if he didn’t know . . .

It was a small thread, but sometimes—if you’re careful not to break it—you can pull on a small thread and unravel a whole garment.

“Goodnight, Roland.”

“Goodnight, Jamie.”

I closed my eyes and thought of my mother. I often did that year, but for once they weren’t thoughts of how she had looked dead, but of how beautiful she had been in my early childhood, as she sat beside me on my bed in the room with the colored glass windows, reading to me. “Look you, Roland,” she’d say, “here are the billy-bumblers sitting all a-row and scenting the air. They know, don’t they?”

“Yes,” I would say, “the bumblers know.”

“And what is it they know?” the woman I would kill asked me. “What is it they know, dear heart?”

“They know the starkblast is coming,” I said. My eyes would be growing heavy by then, and minutes later I would drift off to the music of her voice.

As I drifted off now, with the wind outside blowing up a strong gale.

* * *

I woke in the first thin light of morning to a harsh sound: BRUNG! BRUNG! BRUNNNNG!

Jamie was still flat on his back, legs splayed, snoring. I took one of my revolvers from its holster, went out through the open cell door, and shambled toward that imperious sound. It was the jing-jang Sheriff Peavy had taken so much pride in. He wasn’t there to answer it; he’d gone home to bed, and the office was empty.

Standing there bare-chested, with a gun in my hand and wearing nothing but the swabbies and slinkum I’d slept in—for it was hot in the cell—I took the listening cone off the wall, put the narrow end in my ear, and leaned close to the speaking tube. “Yes? Hello?”

“Who the hell’s this?” a voice screamed, so loud that it sent a nail of pain into the side of my head. There were jing-jangs in Gilead, perhaps as many as a hundred that still worked, but none spoke so clear as this. I pulled the cone away, wincing, and could still hear the voice coming out of it.

“Hello? Hello? Gods curse this fucking thing! HELLO?”

“I hear you,” I said. “Lower thy voice, for your father’s sake.”

“Who is this?” There was just enough drop in volume for me to put the listening cone a little closer to my ear. But not in it; I would not make that mistake twice.

“A deputy.” Jamie DeCurry and I were the farthest things in the world from that, but simplest is usually best. Always best, I wot, when speaking with a panicky man on a jing-jang.

“Where’s Sheriff Peavy?”

“At home with his wife. It isn’t yet five o’ the clock, I reckon. Now tell me who you are, where you’re speaking from, and what’s happened.”

“It’s Canfield of the Jefferson. I—”

“Of the Jefferson what?” I heard footsteps behind me and turned, half-raising my revolver. But it was only Jamie, with his hair standing up in sleep-spikes all over his head. He was holding his own gun, and had gotten into his jeans, although his feet were yet bare.

“The Jefferson Ranch, ye great grotting idiot! You need to get the sheriff out here, and jin-jin. Everyone’s dead. Jefferson, his fambly, the cookie, all the proddies. Blood from one end t’other.”

“How many?” I asked.

“Maybe fifteen. Maybe twenty. Who can tell?” Canfield of the Jefferson began to sob. “They’re all in pieces. Whatever it was did for em left the two dogs, Rosie and Mozie. They was in there. We had to shoot em. They was lapping up the blood and eating the brains.”

* * *

It was a ten-wheel ride, straight north toward the Salt Hills. We went with Sheriff Peavy, Kellin Frye—the good deputy—and Frye’s son, Vikka. The enjie, whose name turned out to be Travis, also came along, for he’d spent the night at the Fryes’ place. We pushed our mounts hard, but it was still full daylight by the time we got to the Jefferson spread. At least the wind, which was still strengthening, was at our backs.

Peavy thought Canfield was a pokie—which is to say a wandering cowboy not signed to any particular ranch. Some such turned outlaw, but most were honest enough, just men who couldn’t settle down in one place. When we rode through the wide stock gate with JEFFERSON posted over it in white birch letters, two other cowboys—his mates—were with him. The three of them were bunched together by the shakepole fence of the horse corral, which stood near to the big house. A half a mile or so north, standing atop a little hill, was the bunkhouse. From this distance, only two things looked out of place: the door at the south end of the bunkie was unlatched, swinging back and forth in the alkali-wind, and the bodies of two large black dogs lay stretched on the dirt.