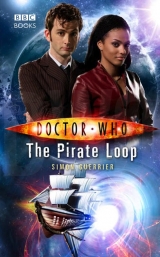

Текст книги "Doctor Who- The Pirate Loop"

Автор книги: Simon Guerrier

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

ELEVEN

The human crew continued to eat canapés, chat and ignore their inevitable doom. Martha couldn't bear even to watch them. She could feel her own heart beating, a sudden sense of herself being alive, of wanting to be alive.

She looked round at the Doctor, busy at the controls of the transmat booth, trying to make it do anything that might help them. He'd used the sonic screwdriver, he'd also used his fists. Nothing seemed to be working. But he kept at it, and she started to think he was just trying to keep himself busy. So he wouldn't have time to think about being trapped. So he wouldn't have to meet her eye.

Martha couldn't help but think back to what the Doctor had said in the TARDIS, when she'd been begging him to bring them here. He'd said there were rules, that they couldn't get involved and they couldn't change anything. And now the two of them were caught up in the same fate as everyone else.

It could be brilliant, flitting through all time and space meeting all kinds of people. But Martha had seen enough people killed, enough terrible, awful things, to know their travels came with a price. And she'd known there was going to be trouble on the Brilliant – that it was going to disappear. The humans and badgers and Mrs Wingsworth had been doomed even before the Doctor set the controls of the TARDIS... And now she and the Doctor were doomed with them.

She made her way over to him. 'You can't get us out of this,' she said. 'Even if you get that thing working.'

He looked up at her. 'Can't I?'

'It would change history,' said Martha. 'And you can't do that. You said there were rules.'

'Rules?' asked Captain Georgina, coming to join them. She seemed to be taking everyone's certain deaths quite easily. Perhaps, thought Martha, it would make her look less effortlessly beautiful if she allowed herself to panic. Or perhaps she just knew there was nothing she could do. Martha's dad always said you should only worry about stuff you actually had any control over. The other stuff would just happen anyway. It was what he usually said when he was arguing with Martha's mum.

'Well, not rules as such,' said the Doctor. 'We have responsibilities. You see, we're sort of from the future and the Brilliant disappeared.'

'I see,' said Captain Georgina.

'You do?' said the Doctor. Martha knew he enjoyed it when people freaked out about time travel.

'I'm fully briefed on the implications of the experimental drive,' said the captain. 'It stands to reason where this technology was leading. I assume you've come back to fix the problem for us.'

'Um,' said the Doctor. 'Yeah, well I was gonna see what we could do.'

Captain Georgina nodded. 'Then we sit and wait it out,' she said.

'Well, yes,' said the Doctor. 'But that's not what Martha was asking. Not can we get out of this, but if we could, then should we?'

'You're telling us it's wrong?' asked Captain Georgina.

'Wrong is bad,' said Archibald, coming over with a tray of blinis.

'So is it wrong to tamper with reality like that?' said the Doctor. 'To come back from the dead?'

'The experimental drive causes problems with causality anyway,' said Captain Georgina. 'Even just starting it up affects what we think of as reality.'

'That's right,' said the Doctor. 'But that's not just true of your clever engine. Look, you change history just by doing anything. Or not doing anything. What you do, what you strive for, every choice you ever make. That's what builds the future.'

'But you only get one go at it,' said Martha. 'Normally, I mean. If you get it wrong, that's tough.'

'You have to deal with the consequences of what you do,' said the Doctor.

'Aw,' said Archibald. 'Do we 'ave to?'

'Yes,' said the Doctor. 'It's called being a grown-up.'

'Sounds really boring,' said Archibald.

'Sometimes it would be good to be able go back and do things again,' admitted Martha.

'You'd think so, wouldn't you?' said the Doctor gravely. 'But it doesn't work like that. It's like telling lies. You can never just tell the one fib, can you? Sooner or later you've got to tell another, just to back up the first one. A week later, you're juggling a whole intricate patchwork of lies on lies on lies. You can't remember what you've told different people, and you're probably not entirely sure what the real version is any more. So it's only a matter of time before someone catches you out or you just plain forget something and it all collapses, boom!'

'I've an ex-boyfriend you should explain that to,' said Martha.

'Before or after he's an ex?' he said.

For a moment Martha could see the Doctor turning up on a rainy night in 2005 and sorting out one particular row. 'OK,' she said, unsettled by what she'd just been offered. 'It's just a world of messy and complicated, yeah?'

'That's it,' said the Doctor. 'I hate all that tricky continuity stuff.'

'We just have to accept the hand we're dealt,' said Captain Georgina.

'No cheating,' said Archibald.

'Well...' said the Doctor, and his eyes glittered. 'Our real problem is how we get out of this mess without changing history. Which needs us to be very clever indeed. If only we had someone with an innate understanding of the space-time continuum. Someone with several lifetimes' experience doing this sort of thing.'

'Oh,' said Martha laughing. 'You mean like the last of the Time Lords?'

'Yeah, I think he'd do,' grinned the Doctor. 'If only we could find him.'

'I see,' said Captain Georgina. 'You can help us, can you?'

'Can you?' added Martha.

The Doctor met her eye. 'I'm working on it,' he said.

He continued to work on the transmat booth for hours. Archibald and Captain Georgina eventually left him to it and went back to the canapé-scoffing party. Martha felt torn between joining them and staying with the Doctor.

'You want anything to eat?' she said. He didn't even seem to hear her.

She made her way over to the human crew and badgers. They all seemed to be having fun, chatting, telling jokes and stories, and generally not giving a stuff about the problems facing them. Thomas made an unsubtle effort to impress Martha with a story about how fast he liked to drive. Archibald, grinning with new confidence, told the old joke about why pirates are called pirates. And Captain Georgina responded to this with a light and tinkling laugh. Martha smiled to herself. Was Archibald flirting? Was Captain Georgina? Did they even know themselves?

Only she and the Doctor seemed bothered that the ship might explode at any moment. Or maybe they were all just making the most of whatever time they had left. She felt glad for the three badgers, so clearly loving every minute of it. But she was also envious of them, and their ability to fit in. It wasn't just being from Earth that made her an outsider. Now she'd met the Doctor she couldn't just stand idle.

And that was when it struck her. They had a chance. Or at least, they had a choice. A choice between just waiting for the Brilliant to explode and daring to brave the pirates.

Archie,' she said.

Archibald grinned at her. 'What you get,' he said, 'if you cross a robot with a pirate?'

'Never mind that now,' she told him. 'I need your help.'

'OK,' he said.

'What do you think the rest of your lot would make of the canapés?' she asked him.

'Huh,' he said. 'They'd like the cheese ones best.'

'What is it?' asked Captain Georgina. 'Have you thought of something we can do?' Around her, other people's conversations died down. The party had been a pretence; they were all desperate to escape.

'Yeah, I think so,' said Martha. 'I think we have a chance. If we can get out of the loop, we just need Archie, Joss and Dash to tell their friends what they found here. The food, the drink, a whole different way of living.'

'But they want the experimental drive!' said Thomas.

'No,' said Martha. 'Whoever's hiring them does. And while they do what they're told, the badgers are just slaves.'

'No one,' said Dashiel slowly, 'owns anyone.'

'Exactly!' said Martha. 'That's what you have to tell them!'

No one said anything. The badgers looked at one another, the humans watched with bated breath. And then Martha jumped at a voice that came from right behind her.

'I think that's brilliant,' said the Doctor.

'Yeah?' said Martha, swelling with pride.

'Oh yeah,' said the Doctor. 'Double A-star and probably a badge.'

'But will it work?' asked Captain Georgina.

'Oh,' said the Doctor, 'who knows? But you've got a choice between certain death and a small hope of surviving. You're a clever lady, you work out the maths.'

And you can get us out of the loop?' she asked.

'Oh yeah,' said the Doctor. 'Easy. I just need to get down to the engine rooms and swap some stuff around. I've got some equipment down there which can help.'

'But how will you get there when the transmat isn't working?' asked Martha.

'Well, it's not working quite like it should be,' admitted the Doctor. 'But I've been talking to it. And I think we've reached an accommodation.'

'Doctor,' said Martha, carefully. 'You're not going to do anything dangerous, are you?'

'Of course I am,' he said.

'If anything goes wrong...' said Martha.

'Then we take the consequences,' he finished for her. 'That's how it works.'

'You can program the engines from here,' Captain Georgina told him.

'I already have done,' said the Doctor quickly. He seemed pleased to move on from Martha's concern for his safety. 'But I need the systems up here and the stuff down there to be doing slightly different things. That's how we jump-start the ship. It's quite clever, really.'

'So we're going down to the engine rooms?' asked Martha, already making her way over to the transmit booth.

'Er,' said the Doctor. 'I am,' he said. 'I kind of need you to stay here.'

'Oh,' said Martha. 'OK, whatever you want.'

'Really?' he said, surprised.

'Well it's going to be important, isn't it?' she asked.

'Oh yeah,' said the Doctor, a little too quickly. 'I need you to be up here watching.'

'Watching what?' she said, looking back at the horseshoe of computers. 'I don't know how these controls work.'

'Not the controls. I don't wholly trust the badgers. And I really don't trust the crew.' He grinned. 'I quite liked Mrs Wingsworth.'

But something in his eyes didn't feel quite right. She folded her arms. 'What?' she said.

'What?' he said back at her, feigning innocence.

'There's something, isn't there?' she said. 'You're going to tell me.'

'All right,' he sighed. 'The transmat might not be much fun. It's meant to be instantaneous but we know there's some kind of delay. And if I'm lucky I won't notice while I'm inside it...'

'But if you do?' asked Martha, her eyes wide in horror. She didn't know quite how a transmat worked but imagined him scrambled like the eggy material that still blocked the doorway.

'Oh, I'll pull together,' he said lightly. Before she could stop him he'd opened the door of the transmat, was inside and at the controls. 'Play nicely while I'm gone,' he said.

'But Doctor,' she said, tugging on the door which refused to open. 'I don't even know what you're going to do!'

'You know what?' said the Doctor. 'Neither do I.' He grinned. 'Ah well. Sure I'll think of something.' And with a pop he vanished from the booth.

TWELVE

It didn't hurt quite as much as he'd expected. Yes, it hurt a lot. And yes, a human being would never have survived. A transmat machine takes you apart and puts you back together again, but the whole thing is over so quickly you shouldn't even notice. This one had taken its time. The Doctor had felt himself being slowly reassembled, an agonising torture where there was not enough of him to scream. But as he emerged from the transmat booth into the dark, noisy engine rooms, he felt pretty much OK.

His legs buckled underneath him, and he fell face first onto the floor.

He struggled to get up again and found his limbs weren't quite responding. His arms and legs tingled with pins and needles, like they did when he regenerated. Perhaps that's what he'd done, his body responding automatically to being pulled apart. He struggled to reach a hand up to his face. His fingers prodded familiar skin, tight over prominent bones. He had the same thick hair and long, furry sideburns and, though his mouth tasted all peculiar, his teeth seemed to be the same shape they'd been before. So, he was still the same man for the moment. But it said a lot about what he'd just been through that he'd not been sure.

As feeling came back to him, he heard hesitant, shuffling footsteps. It took effort to sit up, but going slowly he managed it. A group of mouthless men in leather aprons and Bermuda shorts huddled a short distance from him, in the narrow alleyway between the huge, dark machines. One mouthless man gestured and pointed to the far end of the engine rooms. The Doctor looked, squinting to make sense of what he saw. A tall, skinny man in a fetching pinstriped suit was stepping into a wall of scrambled egg.

'Huh thuh,' said the Doctor, watching him vanish. He had meant to say, 'Is that really what my hair looks like from the back?'

He sat there, recovering and, after a while, the mouthless men brought him a mug of tea with a picture of a sheep on it. His hands shook as he held the mug, but with each sip he felt better and better. The engines around him filled his head with noise and his skin felt itchy with grime. Yet the dark and solid machinery seemed immaculate, the air rich with the stink of detergent; he just imagined the dirt.

'Thank you,' he said as the mouthless men helped him up on his feet. They let him walk unaided but kept close in case he fell. The Doctor made his way to the wall-mounted controls for the experimental drive. A small porthole let him look into the machine itself, and he gazed in on the eerie light. The light was just the same as that inside the TARDIS's central column. It swirled and murmured, restless and alive.

'OK,' said the Doctor, checking over the engine controls. He made a mental note of the readings and how they differed from those upstairs on the bridge. The trick was then to get the TARDIS to make up for the difference. That would, he hoped, break them from the loop. Adjusting dials and switching levers, he felt the old speed and dexterity returning to his fingers. His thoughts were starting to speed up, too.

He spun on his heel, surprising the mouthless men, and hurried down the alleyway between the large machines to where the TARDIS waited. It took a moment to find the key and then he was inside. As always, stepping over the threshold filled him with sudden ease. His head felt clearer, his body less sore.

The console still sparked and smoked from where the ship had crashed into the Brilliant. The Doctor hurried over, swatting away the smoke and working the various controls. Yes, he could see it clearly now. They'd crashed because the Brilliant sat just outside space and time. Like jumping onto a moving bus, only it turned out to be rushing towards you.

The gravitic anomaliser protested as he wound it round to eight. He keyed in the values of the Brilliant's two different Kodicek readings, and fired up the TARDIS's temporal shields. The idea was that he could give the Brilliant a nudge at the right angle and the starship's own systems would do the rest. He wouldn't even need to use the TARDIS's own reality-warping talents.

And then a thought struck him. A brilliant one.

He hurried round the console, pulling up the floor grating to expose the thick black cables coiling underneath. A bit of sonic screwdriver action, and he'd separated one of the connections. Bits of what might have been scrambled egg dripped from the open ends of cable.

He hurried back out of the TARDIS, bringing the cable so that it spooled out behind him, still connected at one end to the machinery of the TARDIS. It took a bit of negotiating the cable through the alleyway between the Brilliant's huge and noisy engines, like getting the flex from a vacuum cleaner to fit round chairs and tables. But he reached the controls of the experimental drives, and then just had to find something that he might connect the cable to. The control desk of the experimental drive had input ports, but none quite fitted.

'Ah,' said the Doctor. 'Should have thought of that.'

He looked quickly all around for something that might help, but he knew there was little he could do. And then one of the mouthless men came forward with what looked like a squeezy bottle of ketchup. The Doctor tried plugging the TARDIS cable into each of the different ports, and once he'd identified the best fit the mouthless man sealed it in with the jelly-like sealant that oozed from the squeezy bottle. It was the same fast-acting, impossibly strong stuff that had sealed the hole in the side of the ship when Archibald's capsule had torn through it.

'Well done you,' said the Doctor to the mouthless man as he tested the join was secure. In fact, the join was stronger than the cable was itself. The Doctor hurried back to the TARDIS.

A group of mouthless men huddled at the doorway, peering into the huge interior but not daring to venture any further.

'Well?' said the Doctor. 'Aren't you going to say how it's bigger on the inside?' The mouthless men turned to look at him. 'No, I guess not,' he said. 'Look, you can ride with me but it's going to be bumpy. Or you can stay here, which will probably be the same. Your choice.'

It was a little disappointing, but none of the mouthless men would come with him. He shrugged, ducked between them into the TARDIS and dashed over to the controls. The mouthless men watched him from the open doorway, the thick black cable snaking between their legs back to the controls of the experimental drive. He could see them wanting to ask him what he had just done. 'I've bolted your ship to mine,' he said. 'And now I can run your systems from here. But my ship can also compensate for some of the loopy stuff happening. So I might even be able to control aspects of the loop itself. And then we're laughing. Ha ha!'

The mouthless men nodded, though not as keenly as he'd have liked. Still, there was little he could do about that now.

'You probably want to stand back a bit,' he told them. They retreated in fear as he worked the controls in front of him. It had been a while since he'd last tried to take off with the doors still open, he thought. Probably because it was such a dangerous thing to do. Dangerous and reckless. Dangerous and reckless and irresponsible. Just his thing, really.

He released the TARDIS handbrake.

With the familiar low rasping, grating from deep within its own strange engines, the TARDIS began to warp the material of space-time around it. The Doctor stood resolute at the controls as what might have been a tornado tore through the open doors and sent papers, sweets and his 1966 Martin Rowlands trimphone whirling all around him. Where before the open TARDIS doors had looked out into the engine rooms, the way was now blocked by a wall of pulsing, straining scrambled egg. The tornado whirled ever faster round and round him, howling and shrieking in time to the noise of the TARDIS's engines.

And then it was suddenly over, the sweets and paper and designer telephone crashing to the floor.

'Said it was easy,' said the Doctor, though only to himself. And he bounded through the open, eggless TARDIS doors and back into the Brilliant's engine rooms. 'Oh,' he said, stopping suddenly. 'I don't think that's quite right.'

Outside, the engine rooms lay silent. The huge machinery stood perfectly still. There was no one about.

'Hello?' called the Doctor. No one responded. 'I know you can't speak,' he called out. 'But maybe you could hit something, make some kind of noise.'

Again there was nothing but silence.

Moving slowly, warily, the Doctor followed the thick black cable from the TARDIS as it wended along the alleyway between the still machines. The cut-off end of the cable lay on the floor in front of where the controls for the experimental drive had been. It had been cut off with a knife.

'Ah,' said the Doctor. 'That shouldn't have happened.'

He examined the empty space, and it was clear the experimental drive had been torn from the housing in which it had been secured. For a moment, he wondered if perhaps realigning the Brilliant had made the drive implode, which would be quite a neat solution to everything. But in his hearts he knew that that couldn't have been what had happened.

The walls of the engine room were a mishmash of car-sized patches of red-jelly sealant. The Doctor could see that at least six or seven pirate capsules had torn their way aboard the ship and then torn their way off again. Any of the mouthless men who'd been in the engine rooms when the pirate ships tore through the hull would have been quickly sucked out into space.

'Ah,' said the Doctor. 'I must be running late again.'

Desperate to find out what had happened to Martha, he grabbed the cut-off end of the cable, and quickly gathered it back up into the TARDIS. He'd repair the link later, when he knew Martha was OK. Locking the door of the TARDIS, he made for the transmat booth. With the ship realigned it should be working properly once again.

He keyed the controls and nothing happened. Annoyed, he checked over the transmat systems. The booth he was in seemed to be in good working order, but it couldn't reach the booth upstairs.

A chill ran through the Doctor.

He dashed down the alleyway between the huge machines, to the door that he'd only ever seen before blocked by scrambled egg. There was no egg now, and he ran out into the plush-carpeted passageway. The wood-panelled walls were patched with more car-sized holes where pirate capsules had punched through.

He ran left, left again and then right, and took the stairs three at a time. Halfway up the staircase to the ballroom, he saw the first dead body.

A blue Balumin man lay sprawled at the top of the stairs, a terrible, blank expression on his face. Further into the ballroom lay two more blackened bodies.

The Doctor made his way into the cocktail lounge, expecting to see more dead. But the cocktail lounge was empty, the whole bay window that looked out onto the Ogidi Galaxy now a great long patch of jelly sealant. Most of the Balumin would have died in space, the pirates had shot the rest.

Upstairs, the walls were likewise patched with red jelly sealant. The Doctor made his way along the crew's small quarters and through to the door to the bridge. There was no wall of scrambled egg blocking his way, and he stepped through quickly. The horseshoe of computers had been smashed apart. And in the gap lay the dead body of Captain Georgina Wet-Eleven of the Second Mid Dynasty.

There were a few other corpses around, but there was nothing to be done for them now. Instead, the Doctor moved quickly past them to examine the sparking remains of the computers, but they could tell him nothing. He had no idea how long it had been since the loop had come apart, nor where the pirate ship had got to now. He had lost Martha to them again. But, as he'd promised himself before, he would do whatever it took to find her.

He rummaged in the pockets of his suit jacket for a bit of paper and a pen, and almost cut himself on the dagger he'd confiscated from the unconscious Dashiel all that time ago. When they'd still been enemies and people couldn't die.

'Doctor?'

He spun round on the heel of his trainer. The egg-shaped, orange and tentacled Mrs Wingsworth stood in the doorway of the bridge. She no longer had any of her extravagant jewellery and her flimsy dress had been spattered with muck and blood.

'Hi,' said the Doctor.

'Whatever are you doing, dear?' she asked.

'Writing a note in case there were any survivors,' he said. He left the note on the wreck of the horseshoe of computers and hurried over to her. 'Are you all right?' he asked.

'Oh, we soldier on, dear,' she said. 'But you know there's nothing to drink downstairs.'

'Shocking,' he said. 'I'd complain.'

'I did!' said Mrs Wingsworth, laughing. 'Only there's no one here to take the slightest bit of notice!' The laugh died in her throat, but the Doctor could see her refusing to let him see how scared she'd been, how much she'd suffered.

'It's going to be all right,' he said. 'I promise you.'

Mrs Wingsworth reached out her tentacles to him. 'Martha!' she said, a tremor in her voice. 'She said I had to find you!'

'And you have,' said the Doctor kindly. 'It's going to be all right. I'm here now. You just have to tell me what I missed.'

Mrs Wingsworth, tears streaming down her egg-shaped orange body, did her best to explain.

'The pirates,' she said. 'They came. They killed everybody. And no one's coming back.'