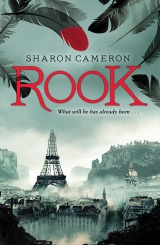

Текст книги "Rook"

Автор книги: Sharon Cameron

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

“Idon’t know, Tom. What should I have done?” Sophia leaned back into the pillows, having just vomited for the second time into the bowl Orla held out for her. She was glad she had at least waited until now for that humiliation.

“Let her alone,” Orla chided. “She’ll rip that cut open if she keeps this up.”

Tom stopped limping about his room and sat down in the armchair, thumping his stick to take out his frustration. His room was on the ground floor, in the oldest part of the house, thick-walled, gloomy, and away from the nicer apartments. Which was the way he liked it. It was as far as Sophia had gotten after she left the sanctuary.

“It is well sewn,” said Orla, peeking beneath the blanket, where Tom could not see. She handed Sophia a wet cloth for her face.

“I’m shocked a man like that would know how to do it,” Tom commented. “And how in the name of the holy saints is he getting out of the north wing?”

Sophia shook her head. She didn’t know. There was much, she now realized, that they did not know about René Hasard. They might not know anything about him at all. “And where is the other one?” Tom continued. “What’s his name?”

“Benoit,” Orla replied.

Tom turned to Sophia. “Did Hasard mention where he was?”

She shook her head. They’d been careless about Benoit—watching René, or trying to, but not his manservant, misjudging Benoit’s potential in the same way they had always depended on others underestimating Orla. A stupid mistake. The kind that could get someone’s head cut off.

“Then the question is,” Tom said, “how soon might there be a hue and cry over his missing master?”

Sophia sighed. “Orla, go to the north wing and see if you can find Benoit. Tell him that René sends word that he’s with his fiancée, and might not return until just before dinner. Make it seem … you can make it seem as if he’s in my rooms, if you want. I doubt Benoit will question you then.” Sophia ignored the soft swearing coming from Tom’s chair. “We’ll think of some other excuse before dinner. Perhaps Monsieur will be ill.” Likely he already was. She looked to Tom. “Do you agree?”

He nodded. Orla, grim as ever, patted her head once and hurried out Tom’s door. Tom leaned back in his chair, rubbing a rough chin. “LeBlanc knew the Red Rook would come. It was a trap.”

“But I think,” Sophia ventured, “that he did not expect the window.”

“Perhaps not.”

Sophia closed her eyes, trying not to remember the way it had felt to pull a knife out of a dead man. “Is there news from the Holiday?”

“Oh, yes. It’s all over the countryside. Burglary and murder. They’re tracking the scent west. Spear is with them. He was worried sick when you didn’t come back. I thought he was going to tear the house down.” Tom waited, but Sophia didn’t say anything. “And the dead man was a stranger to you?”

“Yes. Was he LeBlanc’s?”

“Must’ve been. He was a stranger to everyone. And who do you think killed him?”

Sophia’s eyes opened. “Wasn’t it me?”

“Did you clean your knife?”

“No.” Sophia thought back to the fuzzy dark with the foxes barking and the unnatural silhouette of a knife sticking out of a chest. “It wasn’t my knife,” she said suddenly. “The handle was too thick. Did I have two knives when I came in here?”

“No, only your own. Where is the other knife, then?”

“I don’t know.”

“And more to the point, whose knife was it, who put it into the stranger’s chest, and who else might have seen you climbing out a window of the Holiday?”

They were questions neither of them could answer.

Tom said, “We are in a fix, my lovely sister.”

She nodded.

“But I am very glad you’re not dead.”

She smiled wanly from his pillow. She had considered long ago what might happen on one of the Rook’s missions, what was sure to happen if she was caught. She had thrown her death on the scale, weighed it out against her future, and made a choice. And that choice had been a secret shame to her. It hadn’t been that many generations since the chaotic centuries following the Great Death, when all that could be expected from life was feuding, war, and the struggle to survive it. Personal fulfillment just wasn’t one’s top priority when the children were starving or raiders were cresting the hill. But Sophia Bellamy had not been born into those dark times. She had been born into an enlightenment, an age of privilege, art, education, living in a way that her Bellamy ancestors would not have dared to dream. And she’d been more than willing to risk it, everything her forebears had struggled to achieve, for nothing better than adventure and a challenge to her wits. When it came down to it, Sophia Bellamy simply feared boredom more than she feared death.

But all of that had changed the first time she crawled into the Tombs. Being the Red Rook hadn’t been about adventure then. Suddenly it was about blood and disease and death and the children who watched their parents’ heads being tossed into coffins. It was about injustice and a city possessed. It was about stealing from Allemande and cheating the Razor. And knowing that, in her opinion, only made her actions all the more reprehensible.

What sort of person went to the lengths she did to dam a flood of evil, and then lay awake at night dreading when there would be no more evil behind the dam? Without the Red Rook, she would be nothing but the girl she was before and the girl she would become: a wife, doing just as her mother and grandmother had, doomed to managing a house and dinners with Mrs. Rathbone until the end of her days.

The truth was that Sophia Bellamy went to the Sunken City because she didn’t know who she’d be anymore if she didn’t. If she was caught, she wouldn’t be sorry. She would only be sorry that the people she loved most would bear the pain of it.

“Tonight,” Tom said, “let’s go on with this dinner as planned. Can you do it?”

Sophia nodded. She had to.

“Hasard will be sick, and we’ll send Benoit for Dr. Winnow just before dinner begins.”

She nodded again. Winnow lived fifteen miles away and was nearly deaf.

“Then, after dinner, we can go to the sanctuary and deal with your fiancé.” Tom sighed. “A shame, really. He seemed so harmless at first.”

He was not harmless now. Sophia stared at the finely woven fibers of Tom’s linen sheets. Either the motion of her head or Tom’s words were making her ill.

“Blimey, Sophie,” Tom said suddenly. “Don’t look like that. I wasn’t planning on murdering the man. I definitely prefer to bribe him. What do you think he wants?”

Sophia let out her breath. What did René Hasard want? She remembered the way his words had moved the curls near her ear. Had he wanted her to turn her head? That the thought had even crossed her mind seemed like treachery; that she was thinking it yet again was a capital offense. She’d never kissed anyone before. Had never wanted to. And the peck she’d given Spear Hammond when she was six definitely did not count. She felt her face flushing and blinked long, in case Tom could see her thoughts. She said, “I have no idea what René Hasard wants.”

“Then that’s what we have to find out tonight. What will be enough to get him to betray his cousin and his city? And to drop this marriage contract.”

Sophia looked up sharply. “What about Father?”

“Father may just have to face up to it, Sophie. I wish we could’ve kept things going until I could prove for the inheritance, though God knows how I was going to do it …” Tom glanced once at his leg. “And this fee is mental, anyway. It’s supposed to keep us from marrying outside the Commonwealth, when really it just makes certain that every strapped-for-cash father on the island gets in a ruddy boat to go find a son-in-law.”

Sophia shut her eyes, heart aching like her head. If René was working with LeBlanc, then maybe there would have never been a marriage fee in the first place. But the letter had said he might go through with it. She thought about Bellamy House, every beloved and cobwebbed inch of it, and the money she would have given Tom, for a business. What price would she have paid for those things? “Tom …”

“Please, Sophie. It’s one thing for Father to sell you off to a prat. It’s another to sell you off to spend your holidays with the likes of LeBlanc. All in all,” Tom said, “if it’s between the land and my sister, I’d much rather keep my sister.”

She didn’t know what she wanted anymore. “And so Father will go to prison.”

Tom played with the head of his walking stick. “For five years he did little, and for three years he’s done nothing. I know he’s lost without Mother, but … they’re his mistakes, Sophie. Not mine, and not yours.”

Sophia sighed. Then her fiancé would just have to be bribed. But if she pulled out those scales again, weighing the things René Hasard might wish for against what she and Tom could give, she was very afraid that the Bellamys were going to come up wanting.

They were going to come up wanting no matter what.

The waiting hall outside the Bellamy dining room was small but formal, awash with soft, mirrored light that did not show the shabbiness of the upholstery. They only used this room when important guests came to dinner, and when Sophia entered, that guest was already there.

Albert LeBlanc was again in his blue jacket, a white shirt and meticulously arranged necktie beneath it. Sophia smiled brilliantly over his offered hand. All of her was brilliant; she and Orla had made sure of that.

It had been tedious and exhausting to get all the mud and blood off her skin and hair, especially without soaking her still-oozing cut. She’d spent a good part of the day in bed. But she was back in the dark hair now, black paint around her eyes and plenty of powder to cover paleness and shadowed circles. Her dress was a rich burgundy, a color originally chosen to set off her skin, tonight chosen to not immediately show a bloodstain. She’d never been more grateful for a tightly tied corset, though there was nothing she could do about the terrible ache in her head.

“Good dusk, Miss Bellamy,” said LeBlanc.

“You look quite pretty tonight, Sophia,” said her father. He seemed sad about it, and a little surprised, as if he’d just remembered that she was not a child, and that he was marrying her off to a stranger. Sophia kept her manufactured smile in place, raised her eyes, and saw that Spear stood just beyond Bellamy, filling one corner of the waiting room like a blond and marble statue.

“Hello, Spear. I thought you were away on the hunt. After a criminal, wasn’t it?”

He came to take her hand. “The chase was called off.” His eyes bore back into hers, as if he would tell her something, but couldn’t.

“Didn’t the foxes have the scent?” she asked.

“They did,” LeBlanc answered. “But I chose not to pursue the matter, and so left the chase. Petty thievery is not worth my time.”

“But …” Sophia glanced at Spear, and then back to LeBlanc. “I thought Tom said that a man had been killed?”

LeBlanc gave a dismissive wave. “Nothing was taken, Mademoiselle, and why should I be concerned with a quarrel among thieves?”

“The dead man was a thief, then?”

“Really, Sophia,” said Bellamy. “I wonder at Tom putting these stories in your head. It’s not decent conversation. I should speak with him, I’m sure …”

While her father talked, Sophia leaned just a little toward Spear, to catch his low, quick words. “He rode straightaway from the hunting party on the flatlands. No way to follow without being seen. Missing from just after highsun until now. And are you all right? I …”

“And where is Monsieur Tomas Bellamy?” LeBlanc was inquiring. “I was disappointed not to be greeted by him. I had wished to …”

Tom came into the room then, his stick tapping, brown hair curling against the scarlet of his uniform, and if Sophia had not happened to glance at LeBlanc at that very moment, she would have missed it. LeBlanc’s colorless eyes had widened just slightly, the forehead betraying a crinkle of surprise before shifting back to its unruffled exterior.

Sophia turned her head, frowning, causing a nauseating ache in her skull. She found the nearest chair and sat. Obviously, LeBlanc had been surprised to see Tom. But why? Why would he think Tom wasn’t going to come? Because Tom wouldn’t be able to attend? Because Tom was wounded, perhaps? She drew a sharp breath. Wounded last night, while searching LeBlanc’s room at the Holiday?

She heard LeBlanc giving Tom an overly polite, very Parisian welcome. She must have left blood on the ground. Or something had been seen. But surely LeBlanc could not think her brother capable of climbing up through that window? The rope, the height, and the scent moving west, all of it should have exonerated Tom. Unless LeBlanc thought Tom’s bad leg a ruse? One of the few things about the Bellamys that wasn’t!

“Sophie?” It was Spear’s voice, whispering from behind her chair. He had a hand on her shoulder. “Are you sure you’re all right?”

Sophia lifted her eyes to LeBlanc, his face smug as he gazed languidly at her chatting brother. How careful they had been all day, planning every detail to give her an alibi, to protect her from René’s dangerous knowledge, and all the while doing nothing for Tom because they’d thought it was done already. Sophia set her mouth. She was at peace with paying for the crimes of the Red Rook with her life, but she would never allow them to be paid for with Tom’s. LeBlanc was just going to have to think again about the identity of the Rook.

“… my young cousin?”

Sophia’s gaze jumped up, Spear straightening just behind her. She had lost the thread of the conversation.

“Oh,” said Tom. “I believe Monsieur Hasard is …” He looked to Sophia.

“Sick,” Sophia finished for him. “Not feeling well at all. Such a … tiring day, and he was looking so—” She struggled for a word that wasn’t “knackered.” “—so overcome, I convinced him to stay in bed. I was concerned he might have …”

She paused, eyes darting to the door. Fast footsteps were coming down the corridor.

“… that he might have … caught something …”

Someone was running down the hall, the clack of shoes distinct against the multicolored floor tiles. She sensed Spear’s sword hand move. He must have a knife somewhere in his clothes. Then the door to the waiting room burst open, the resulting space filled with a green coat, complete with silver buttons.

“Ah! Here you all are!”

Sophia held her face still, hoping at least she hadn’t made LeBlanc’s mistake of showing her shock. René Hasard stood in the doorway, unshaven, unpowdered hair pulled back into a hasty tail, but with the heavy Parisian voice and smooth manners in full force, brimming with that oblivious cheerfulness she found so annoying. But it didn’t matter now if René vexed every nerve she had. Not anymore. Not when the game was over. No time to discover how he might be bribed, no way to bring him to their side. The Bellamys had just lost. Utterly and completely.

“Tell me I am not late?” he said.

Sophia let the realization settle. Maybe this was for the best. This way it would be her neck bared for the Razor, not Tom’s. And any proof LeBlanc needed was standing in rather handsome dishevelment in the waiting hall doorway, and bleeding just a bit into the bandage beneath her corset. Why could René Hasard never, ever be where he was supposed to be? Sophia threw her shoulders back. Despair made her angry.

“I was just telling your cousin I thought you were sick,” she said to René. “Why, exactly, aren’t you sick?” He must have the constitution of an ox; he should have been sleeping until the middlemoon. Tom cleared his throat, but Sophia just narrowed her eyes at René, daring him to answer. A grin quirked at the corner of his mouth.

“Such a darling,” René said to the room. “And so considerate of my health. You’d have me abed all day, wouldn’t you, my love?”

The discomfort this statement left behind had everyone frowning except Bellamy, who was still trying to work it out, and Sophia, who had been obliged to press her mouth tight against an unreasonable urge to laugh. What a parting shot.

“Always,” she replied slowly, “my love.” Though the look she sent clearly added her preference that he be in an unconscious or perhaps a non-breathing state. It made his grin leap onto both sides of his mouth. She saw Tom’s scowl deepen, felt Spear’s resentment in the air behind her. Then LeBlanc laughed, a sound like snakes slithering across a carpet.

“Well, isn’t that nice,” said Bellamy finally, fidgeting with his coattails. “Young people, so nice …”

Nancy, the cook, appeared in the doorway. “Your dinner is on the table, Miss Bellamy,” she said.

Sophia jumped to her feet, as if she had nothing on her that could hurt, ignoring all the things that did. “Thank you so much, Nancy.” She faced their little party. “Shall we all go through?”

The dining room was Sophia’s favorite in Bellamy House, and she pointed out all its details with minute attention, since it was likely to be the last time she ever saw it. The ceiling and one wall were made entirely of metal and triangular panes of glass, very old—though it did not have the telltale lack of bubbles to make it truly Ancient—the pattern of triangles spreading up and out like a fan, curving to create the ceiling. At some point a singularly uninspired Bellamy had built more of the house right over and around the glass wall, ruining the room with darkness. But her mother had had lights installed into the empty spaces behind the glass, with sconces and hooks for oil lamps, so that on nights like tonight, points of light glittered from every direction, reflecting again and again through the triangular panes.

“Please find a seat, everyone,” Sophia told them. They arranged themselves, Bellamy on one end of the rectangular table, Sophia on the other. René and Spear to her immediate right and left, LeBlanc beside Spear and Tom beside René. Lovely.

She shook out her napkin, then reached over her plate and passed a heavy platter of sea bass and potatoes to Spear, a move that hurt her side intensely. She gave the pain none of her attention. René Hasard had her well and truly on a hook, but she was in no mood to let him watch her wriggle.

“Monsieur Hasard,” she said. “I am so curious about how you’re feeling, and how you spent your time today. No more teasing now. Please tell us all about it.”

“Yes, tell us, Hasard,” said Spear in the resulting pause. “I’d like to know that myself.” Sophia thrust a bowl of carrots at Spear. He was like St. Just at her heels, always the faithful friend. Only this time he had no idea what she was trying to do. If he had, he definitely would not be helping.

“But the answer is so dull, my love,” René replied, as if Spear had not spoken. “Did you not think the night before so much more … stimulating?”

So, Sophia thought, he was getting straight to the point: her whereabouts last night. It was just as well, because she was tiring of the games. She glanced at Tom for the first time and met his startled eyes. This was going to hurt him, but better this pain than the Razor. She gave her gaze back to René.

“Tell them,” she said.

“Sophie …” Spear reached for her arm but she put it under the table.

“Go on,” she encouraged, holding her back straight against the throbbing in her head and side. “Tell your cousin what I was doing last night. He will be so interested.”

There was a soft clank as LeBlanc set down his fork. Again she exchanged a glance with Tom, and there was an expression on his face that she’d never had occasion to see. Her heart slammed rhythmically in her chest, so hard she feared that it was breaking. That look on Tom’s face made her sure that it was. She turned again to René. “Well?”

René’s smile had gone, his lips opening slowly to speak below two very blue, very inscrutable eyes. She didn’t look away this time.

“Well, do tell, Mr. Hasard,” said Bellamy. “A father should never be the last to know.” He chuckled to himself in the silence.

“Miss Bellamy was out of her room last night …,” René began.

A sharp twinge shot through Sophia’s head, but she met René’s gaze without flinching.

“She was out of her room because …”

That corner of his mouth was quirking. How odd that she could be sitting in the Bellamy dining room, her life crumbling into ruins at her feet, wishing just a bit that the person doing the ruining had kissed her after all.

René broke into a sudden smile. “Sophia was out of her room all night … because she was with me.”

Sophia blinked. René ate a carrot. She looked to Tom, who seemed to have deflated in his chair, while Bellamy, having paid attention to the conversation for once, set down his wineglass, distinctly miffed. Spear had not moved a chiseled muscle.

“Oh,” René said, bringing a napkin to his mouth. “Oh, I beg your pardon!” He was playing Parisian magazine René now, minus the hair powder. “But, please, do not misunderstand!” He leaned over his plate to look down the table at Sophia’s father. “Monsieur Bellamy, I would never wish to stain the reputation of my betrothed. Sophia and I were up all night …” His face turned back to hers. “… playing chess.”

“Chess?” Spear repeated.

“Why, yes,” Sophia replied. “Chess.” She offered Spear a bowl. “Creamed peas?”

Spear took the bowl, visibly confused, though not nearly as confused as she was. René was very deliberately removing her from the hook, and she could not fathom why. But by pulling her off, he was also sticking another straight through the chest of her brother. LeBlanc had lost interest in their conversation, his pale eyes watching every bite that went into Tom’s mouth.

“Yes,” Sophia said again, addressing René and the whole table at once. “You have caught me out, I’m afraid. I couldn’t wait to tell them. It must have been humiliating to be beaten so many times. And so thoroughly.”

René smiled. “Except for that once.”

“Yes,” she agreed, meeting the blue fire of his eyes, “except for that once. Isn’t that right, Tom?” Her brother looked up from his plate, where he had been deep in thought. “Tom was acting as chaperone, poor man.”

“He has always been an excellent son,” said Bellamy.

“Thank you, Father,” Tom said.

“Did you ever get any sleep, Tom?” Sophia continued. “There was that one game, it must have been just before nethermoon?”

“Just after, I think,” Tom replied. He looked from Sophia to LeBlanc, who had stopped eating his own creamed peas and was now intent on the conversation. Tom’s brows came down, and Sophia knew he had just seen his danger.

“Yes, just after nethermoon,” Sophia agreed. “Tell them about it, René.”

René launched into an explanation of a game that Sophia recognized to be the only one they had ever actually played, after dinner in the sitting room. This speech was so boring in its precise description of every piece and move, and at the same time such a perfect homage to René’s own cleverness, that Sophia had to admit the whole thing was a stroke of genius. She watched Spear’s face go from incredulous to blank, saw LeBlanc cutting his potatoes into painstaking fourths, her father yawning behind his napkin. She wasn’t sure anyone even remembered what they’d been talking about.

Sophia pushed the food around her plate, trying to pretend she had eaten some of it. The pain in her skull was increasing, the smell of the fish making her ill. And she had no idea what was happening.

“That is all so very instructive, René,” LeBlanc interrupted suddenly, dabbing at his mouth. “But as a member of your family, I think I must point out to you the bad manners of bragging, especially at the expense of your fiancée. You would be sorry, I’m sure, if I had to speak to your mother about it.”

It was the first time Sophia had ever known Spear and LeBlanc to be in agreement. But when she turned to René, she was surprised to see that this mild threat had actually carried weight. René’s smile had tightened, like the grip on his fork.

“My apologies, Cousin,” he said quietly, “and Miss Bellamy.”

His gaze ran once over hers. He looked away again, but not before she had noticed his look linger pointedly for just a moment on her side, the side closest to him. Sophia wrapped her arms around herself, as if she were chilly, squirming her fingers around until she felt a wet patch. Blood. Not much, but it was soaking through. She wiped her fingers discreetly on her napkin and folded it inward, smiling at them all, her head full of words she could not politely utter.

“Though I am glad you brought the particular subject to mind, Cousin,” LeBlanc was saying. “Because I wished to ask—”

“Monsieur Hammond,” René interrupted. Spear looked up, scowling. “Would you find a shawl for Miss Bellamy? She is coming all out in …” He turned to her. “What is the word, my love? Swan skin?”

“Gooseflesh, I believe he means,” Sophia explained. “I’m afraid I didn’t dress warmly enough.” She ignored the instant glances this statement caused to be directed at her bosom; she was too busy trying and failing to understand why René was shielding her. A shawl would cover the spreading bloodstain at her side.

“I have always thought my daughter should dress more warmly,” Bellamy muttered.

René was still talking to Spear. “Perhaps the woman Nancy, or …”

Sophia supplied the name. “Orla. Would you mind finding Orla, Spear? She’ll know which shawl to send.”

“Of course,” Spear said, looking much less thunderous now that Sophia was the one asking. He left the room in a fast, booted stomp.

“I was saying,” LeBlanc continued, taking in every moment of their little drama, “that I would also like to discuss last night.” He took a sip of wine, his signet ring with the seal of the city flashing in the light. “I would like to discuss the person who was in my room.”

The clink of plate and glass stopped. Tom spoke first. “But I thought you weren’t interested in that, Monsieur LeBlanc. You called off the hunt.”

“So I did,” he replied. “But that is because we were hunting the wrong man.”

“How so?”

“Because the man I am looking for is wounded, Monsieur, and there was no blood trail to go with the scent.”

“Wounded?” said René incredulously. “Really, Cousin.”

“And what makes you say this man was hurt?” Tom asked.

LeBlanc’s grin curled. “Because there was blood on the dead man’s sword. And I do not think this man stabbed his own sword into his own lung, do you, Monsieur Bellamy?”

“I don’t like such conversation,” Sophia’s father said, frowning. “Especially at dinner …”

Sophia watched Tom set down his glass, a little smile playing over his face. Of course he had already thought of this. And of course there was blood on the man’s sword. Her blood. The blood that was seeping through her dress at that very moment. She should’ve taken care of the sword at the time. Would have, had she been in a fit state. But she had not been in a fit state. Blimey, she was tired. Her head was pounding to a beat of its own.

“Am I right in thinking this man, this thief who was killed, was a Parisian, Cousin?” René was asking.

LeBlanc nodded. “You are correct.”

“Then perhaps you are the victim of a plot from our city, and should be looking for another Parisian? A traitor to Allemande?”

“Why, yes, René. It is indeed an enemy of Allemande that I seek. But it is a Commonwealth enemy, I think, not a Parisian one. Which brings me to an uncomfortable question, Monsieur Bellamy.”

This time he was addressing their father, who Sophia was certain had not been paying attention since the talk of a stabbing. She leaned back in her chair. The lights behind the glass were wavering, blurring her vision.

“I apologize for asking during your excellent dinner,” LeBlanc continued, “especially as we are to be family. But I have a witness who will swear to a Bellamy horse riding away from the inn after the murder of the Parisian. And this witness will also swear to a Bellamy being on the back of this horse.”

More silence at the table. Sophia’s pain multiplied, a persistent pressure trying to split open her forehead. Not Tom. Anything but Tom. She knew she had to do something, but she couldn’t think what.

“A horse …,” said Bellamy, voice trailing away in confusion.

“Sophie, are you all right?” Tom said, at the same time that René spoke something soft and harsh beneath his breath. The word had been “liar.”

LeBlanc leaned forward. “What did you say, Cousin?”

“I said I believe your witness to be a liar, Monsieur. I have already said that both Monsieur and Mademoiselle Bellamy were with me last night. Unless you are accusing their father, of course?”

Spear’s boots came back into the glowing dining room, their noise an extra ache in Sophia’s head.

“I think, young René,” said LeBlanc, “that we should be very careful who we are calling a liar here. And I also think you should perhaps look to your fiancée. She appears to be in distress.”

Sophia felt herself sliding from her chair. The world had shrunk to little pinpoints of glass and light, fear and fractured thoughts. Then there were arms around her.

“No, Hammond. I have her. Put that shawl over her.”

She smelled wood and resin. Good. René knew not to rip her stitches. Not to show the bloodstain. No one could see the bloodstain.

“Women,” LeBlanc said from some distant place, “are always prone to such things when upset …”

The starry pinpoints of light behind her eyes shrank, brightening once before they went out.

One of the flames behind the glass over LeBlanc’s head went out, a puff of smoke glazing the triangular pane with a thin film of black. Tom watched René carry Sophia out of the dining room, Spear and their father following close behind. Tom kept his hands beneath the table. Then he turned back to LeBlanc.

“We should have a conversation, I think,” Tom said.

LeBlanc’s smile came slow. “Indeed.”

“Here?”

“There is no such time as the present. And there is someone I would wish for you to meet. Paul!” LeBlanc called loudly. “Paul! You may come in now.”

The other, seldom-used door to the Bellamy dining room opened. Out of a long-abandoned pantry came a large man dressed in rough cloth, and he was dragging a girl behind him. Her short blond hair was bedraggled, freckled face tear-streaked, blood running down both her lower arms and dripping onto the rug. Paul ripped the gag from her mouth, her sobs becoming louder as four more men came into the dining room, swords drawn.