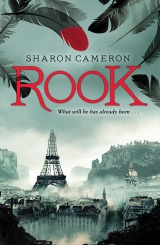

Текст книги "Rook"

Автор книги: Sharon Cameron

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

“What is your opinion, Benoit? Do we find out who he is? Or do we move?”

Benoit sat down in the chair. “It is my belief that men show more truth when they do not know they are showing it. When they know they are caught they will tell you all lies, everything lies. I have told René that I think we should go on as we are, aware that there are eyes, give them nothing to see, and see what they show us. And I will be watching back, of course. He is unhappy with this course, I think.”

Sophia turned her head. “Are you?”

“Yes. But that does not mean I think Benoit is wrong, because he is not.”

Sophia looked at him carefully. “Unhappy” was not near as accurate as her assessment of “ticked.” Then a letter caught her eye, on top of the pile of things René had rescued from the sight of Mr. Halflife. It was that day’s post, freshly fetched from Bellamy House. She snatched the envelope, tore it open, glanced through the contents, and looked up.

“I have the numbers of the prison holes.”

“That has not been posted straight to here?” René sat forward to look at the address.

“Of course not. There’s a … Never mind. It’s forwarded twice.” She read on. “And it’s no wonder it took so long. Jennifer and Tom aren’t in the normal tunnels. They’re deep, in a separate shaft.” Sophia bit her lip. That was a complication. She’d never been down to those cells. “And Madame Hasard is in a cell alone,” she continued, “on the first level …”

“Have they seen her?” René asked, voice very calm. A certain sign, Sophia was learning, that he wasn’t.

“They don’t say. Probably not.”

She watched him frown. He was elbows on knees now, rubbing a hand hard over his rough jaw. He’d been much gentler with hers, she thought. She looked back at her letter.

“We have two days before we sail for the city. I need to go to the sanctuary to get the last odds and ends, and it will take a good part of a night to mix up all the Bellamy fire.” René leaned against the headboard, flipping his coin. “So,” she said, looking back and forth between them. “Do either of you know when Spear will be back?”

The coin flipped, and René cursed softly at the minted silhouette of the premier’s building in the Sunken City. Facade.

“I know you had him followed,” she added.

Benoit replied vaguely, “I do not think we should be worried about Hammond.”

Sophia sighed. That was all the answer she was going to get. And since she didn’t quite think Benoit a murderer, she decided to be satisfied.

René said, “For now, none of us should be alone outside of the house.” A thought of a smile hovered around that corner of his mouth. “And that means no more climbing out of the windows, Mademoiselle.”

So he knew she’d gone out the window, did he? And what was it about her that he hadn’t noticed? She said, “No more climbing out of windows, or just no more climbing out of them all by myself, Monsieur?”

That made him grin. A real one, and it gave her a secret little thrill.

“As for your tasks, we will all go,” said Benoit. “A walk to Bellamy House for some of your things should not give anyone watching much to think on.”

“And what about Mr. Halflife?” she asked.

“Ah,” René said. The coin flipped to face. “We should not go until highmoon. Your member of Parliament will be sleeping well by that time, do you not agree?”

“I have no idea. Where is he sleeping?”

“Did I not tell you?” The grin widened. “Monsieur Halflife has invited himself to sleep at Bellamy House tonight.”

It was strange to see the sanctuary—a place Sophia had always associated with secrets and shadows—so brightly lit and filled with people. The room was deep under Bellamy House, no danger of Mr. Halflife knowing they were there, unless he’d seen them coming across the lawn, which he hadn’t. René had skirted around to Nancy’s flat at the back of the house and found that Mr. Halflife was on the opposite side, near her father’s wing. They hadn’t spotted anyone watching their progress on the road, either, though it was impossible to know who might be wandering the woodlands. Mr. Halflife could be wandering, too, she supposed, but nighttime guests of Bellamy House tended to favor locked doors, an extra candle, and a blanket pulled up to their chins.

Sophia bit her lip, rolling her thick paper into a tube, ready for filling with her brother’s recipe of powders. She wondered what Mr. Halflife expected to accomplish by staying there. If he hoped to find the deed to the Bellamy land lying about on her father’s desk, he would not, as it was currently tucked into the hidden drawer in hers. Or perhaps he was waiting for her to appear one day at the breakfast table, where he could courteously convince her not to marry the man who could save her family and sign away her home instead. She might undo the Bellamys when she blew up the Tombs, but she was fairly certain she would not ruin them out of polite obligation over middlesun scones. And it was hard to seriously fear a man who was afraid of fleas.

She rolled another tube. Tom had left everything written down so they were able to work quickly and almost in silence, Orla waxing and gumming the tubes together, Benoit trimming and greasing the fuses, while René measured the powders and salts carefully per Tom’s instructions. A good job for him, Sophia thought, considering how careful and precise he was being with her. Making sure they were not long in the same room, walking just a little back as they made their wary trip down the road. And he’d chosen the opposite end of the tall worktable now, sleeves rolled up and brows drawn down. It wasn’t very different from the way she’d behaved their first days in the farmhouse, and somehow this seemed to make her paper tubes more uncooperative.

“Tom,” Sophia commented, scowling at her unrolling paper, “is much better at this.”

“These kegs are nearly empty, child,” said Orla. “Go and fill them.” She shoved two small kegs toward Sophia and went back to waxing the tube ends. Sophia knew exactly what this meant. It was, “We’ll go faster without you, so go do something useful instead of something that isn’t.”

She took the kegs and went to the dim end of the room where KINGS CROSS ST. PANCRAS glistened in white and red, the bigger barrels of saltpeter and charcoal lined up beneath it. She ducked behind one of the concrete columns near the wall, taking advantage of a small sliver of privacy from the people across the room, and leaned back her head. Making Bellamy fire was the last thing she’d done with Tom before the Red Rook crossed the sea to rescue the Bonnards. It made her plans, the acknowledged and unacknowledged, seem very tangible.

Then she realized there were booted footsteps coming across the broken tiles. Too heavy for Orla, and Benoit she wouldn’t have heard in the first place. She straightened as René came around the corner of concrete, ceramic bowl in his hand, though not in time to look as if she had some purpose for standing still in the near dark behind a column. He paused, looking her up and down.

“You are not in pain?”

She shook her head, failing to think of a single thing to say. His gaze moved away to the ground at her feet.

“If we are to make more I will need the sulfur as well.” He waited. “Do you know which …”

“Oh, yes. Over here.” She led him to the small cask of sulfur, sitting on top of the saltpeter, and pried open the lid.

“How did your brother learn this?” he asked, wrinkling his nose at the smell.

“Tom? He didn’t. My father did.” She glanced up as she poured a spoonful of yellow powder into the bowl. “Hard to imagine, I know. He must have been like Tom, I think.”

There was silence before René said, “In what way?” She heard the caution in his tone. Interested, when he knew it would be better if he wasn’t. She knew the feeling.

“They were both curious about the Time Before,” she replied. “But for Father, it was the stories of guns that interested him, and the noises they were supposed to have made. He thought they must have needed an explosion of some kind to work. He didn’t believe they were just stories.”

“Sometimes legends can be true, I have found.”

This made her smile. But she was afraid to look up, in case it might scare him away. She talked quick and spooned slow.

“Father studied about it in the Scholars Hall in the city every summer, and he experimented. Down here, I would think …” She hadn’t really considered that before, her father in Tom’s place in the sanctuary, actually striving for something. “And finally … he did it. He made a powder that would explode. He said it was what made a gun work, and that enough of it could blow Bellamy House right off the cliff. That’s what he told Tom, anyway. When we were young.”

René looked back over his shoulder at the worktable.

“That’s why the lamps are covered,” she said. “But it was Tom who learned how to make the explosions smaller, to mix the salts in for sparks and color.”

“But, Mademoiselle.” René had set down the bowl of sulfur and picked up one of her casks, moving to the open barrel of saltpeter as he talked. She followed him. “Would the Commonwealth not pay your father well for such a discovery? A weapon that is not a machine?”

“I think any country still honoring the Anti-Technology Pact would. But Father thought about what could be done, what had been done with such things and … he didn’t want to tell anyone what he’d found. It’s part of what torments him, I think. That if he had gone against his conscience, that maybe … that we wouldn’t be in the predicament we are.”

“I see.” For a moment there was no sound but the dry, grainy swish of the black powder pouring into the wooden cask. René said, “But Tom could sell what his father did not wish to, is that not so?”

“Tom agrees with Father. He thinks the world is better off without it. And I agree, too, actually.”

“But, Mademoiselle …,” René said again. She could see his curiosity. It was in the intensity of his gaze and the way he held his body, in the way he angled toward her, forgetting to fill the barrel. “Tell me this. What if the powder is the true thing, but it is the weapons that are the legend? What if a gun is a … a story my grand-mère would have told?”

“You mean the one who was a liar?”

He cracked a sudden half grin. “You did not have as much concussion as I thought. But how do you answer the question? How do you know what is real, and what is not?”

And wasn’t that the matter of the moment, Sophia thought wryly, eyes on his. They were the same color as that tiny bit of blue in the bottom of her candle flame. She glanced over at Orla and Benoit on the other side of the room, working with perfect understanding despite the lack of a common language, and then back to René.

“If I asked you to go somewhere with me, would you come?”

He hesitated, as she’d thought he might.

“You don’t have to, of course. But if you don’t …” She smiled. “Just think of the curiosity you will suffer.”

René followed her up the long, winding stair, out the door of the sanctuary, and onto the starlit lawns. She’d felt Orla’s surprise when they’d gone, her excuse of “getting something upstairs” evidently not carrying much weight. And she’d seen the look exchanged between Benoit and René, reinforcing their agreement that no one was to go anywhere alone. She looked at the amount of light, and then at René.

“Long way, or the short?” she whispered.

René glanced at the expanse of wall they would have to walk around to get to a door, then the distance up, questioning.

“I’ve been doing some climbing already,” she said. She didn’t choose to tell him why. “My cut hasn’t bothered me, and it’s bound tight.”

She watched him consider the presence of Mr. Halflife, but he only waved a hand. “After you, then.”

Sophia took hold of the window ledge and was up on it like a cat. She scooted across, grabbed the drainpipe, and shinnied up, using the toeholds she and Tom had placed there as children. As soon as she was off the drainpipe and on the roof, René came up after her from the window ledge, taking every other toehold. Sophia crossed the flat roof over her father’s study and started up the latticework that would get her to the more angular sloping gable below her window. She always jumped from the gable to the study roof on her way down, but gravity didn’t allow for such an easy approach from the other direction.

At the top of the lattice she got a knee over the gutter at the edge of the roof, and only just bit back a scream. A hand had come out of the darkness, very near her face. She looked up and there was René, sitting on the sloping tiles, grinning like he’d just nicked her purse. She took his hand and let him pull her the rest of the way up. When she was on her feet she looked back down to the study roof. He must be able to jump to the eaves, she thought. Cheater.

“It is good to be tall, Mademoiselle.” He was still grinning.

“Unfair, you mean.” But she smiled when she said it.

They walked carefully up the gable. Sophia crouched before her dormer window, took a sliver of metal from a small hook under the gutter, and used it to trip her latch. She pushed open both windowpanes, swung her legs through, and hopped inside, René after her. Her room was very dark, and with that slightly stale smell that meant no one had been living inside it for a few days; she hated it when a place that was hers smelled that way. She went to the mantel over the hearth—a formal thing of white marble, glowing ghostly in the starlight from the window—took the tinderbox, and put it in René’s hands.

He accepted it without comment, and she walked across her rugs to the tune of flint on steel. She knelt and pulled a wooden box from beneath the bed. By the time she had brought it to the hearth there was a small fire just kindling, the mantel candles brightening their end of the room. René held one of them up.

“This is your room?”

“Yes.” They were holding their voices low. The quiet seemed to dictate it, even though there were two levels and many layers of hallways and stairs between themselves and Mr. Halflife. She put the box on the hearth rug, settling herself down beside it. René was gazing at everything, turning a half circle with the candle, his hair coming loose from its tie. “What?” she said.

He looked down. “There are little blue flowers. Painted on the walls.”

“Yes,” she said slowly. “Did you forget that I’m a girl? Is it the breeches?”

“No, Mademoiselle, I had not forgotten.” One corner of his mouth lifted. “And that is the fault of the breeches, I think.”

Sophia decided not to ask him what he meant by that. She busied herself with the box, so her hair would hide her telltale flush. “My mother painted the walls, so I don’t want to have them changed. And the curtains are lace, too, by the way. I thought I’d point that out first and save you the astonishment.” When she peeked up, both corners of his mouth were turned up. “Sit with me,” Sophia said, “and I’ll show you what I made you climb a roof for.”

He sat on the opposite side of the box from her, as if suddenly remembering caution, setting the candle on the safer surface of the hearthstone. What had she hoped to accomplish by bringing him up here? What she wanted was to understand him, and this was only going to reveal herself. He pulled up his long legs, waiting.

She brushed the dust from the box—her room was not as immaculate as Spear’s—and opened the lid. Packed inside in soft cloth were pieces of clear glass, square, about the size of a windowpane, leaded together in sets of two. Trapped between the pieces were fragments of paper.

René lifted a pane, holding it near the candlelight. The paper inside the glass was brown, in bits and cracking. “There is writing,” he said. “Printed.” He turned the glass over. “On both sides. How old is this? Did the Bellamys print it?”

“No. It’s much older than that. It’s as old as Bellamy House, we think. My grandfather found them in the walls.”

“They are from Before?” He touched the glass over the paper with a finger, as if he could coax it into speaking. Sophia felt her smile break free at his expression.

“Can you read them?” she asked. “It’s a story.”

He held the glass closer to the light. “St. Just! Is that why …”

She nodded.

“And Marguerite! It was my mother’s mother’s name.”

“The one who was such a liar?”

“No, the other one.” He grinned. “Who was also a liar.”

“There are only bits of the story, but …” Sophia searched through the pieces until she found the one she wanted, scooting around the box to show him. He leaned in to see, caution lost. “This is what I wanted to show you. It says, ‘The dull boom of the gun was heard from out at sea.’ ”

René took the glass in his hands, reading it himself, soft Parisian beneath his breath. “It is real, then,” he said, more to himself than her.

“And look, they call it ‘firing’ the gun.”

“Like Bellamy fire?”

She smiled. “Maybe. I don’t know.”

He gazed at the words. “Does it makes you wonder … what else …”

“What else your grand-mère said that might be true? Like hidden pictures on mirror disks and flying through the air and machines on the moon?”

“Yes,” he said, “just so.” Sophia watched him running reverent fingers over the glass, his hair such an extraordinary color in the candlelight. If he was an actor, he was the best in history.

“This is my favorite.” She pointed at the words. “It says, ‘The walls of Paris,’ and right here, she calls someone ‘Monsieur …’ ” She felt René’s eyes dart up at that. “It’s even spelled the same. And here, she—whoever she is—talks of being condemned to death, and that someone has hidden her children—and herself, I think—beneath some … things in a cart and helped her escape. And the driver is in disguise. He uses tricks to smuggle them out, you see, and he leaves something behind him …” She hunted through the tiny, dim words and pointed.

“What is a ‘pimpernel’?” René asked.

“I’m not sure. Tom thought it might be a flower, or a drawing of one. But I think he uses it like a signature, so no one else will be accused of his crimes, which is rescuing the people from a prison before they can die. No one knows his real name, only the sign of the ‘scarlet pimpernel.’ That’s about all Tom and I could make out, and it took us ages. It’s very hard to read.”

René’s body had gone very still, the little pulse beyond his collar the only movement. The intensity of his gaze on the glass was something she could feel. “And so now,” he said, voice low, “you go to the Sunken City, which was Paris, and you bring the people out of the Tombs before they die. And you leave a rook feather painted red behind you.”

She nodded. He leaned forward, and then all the energy of his gaze was on her.

“Why?” he said. “Tell me why you do it.”

Sophia looked down. Their small fire was already smoldering in the hearth, making the room even darker.

“Come,” he said, almost a whisper. “Tell me.”

Without looking up she said, “Every summer we went to the city to stay with Aunt Francesca, my mother’s aunt. She was Upper City, near the Montmartre Gate, about halfway up,” she explained, referring to the level of the apartment flat, “one of the first women to teach history at the Scholars Hall. And she was busy, and Father absorbed, and Orla never came to the city, because she is afraid of boats. Tom always teases her about that, about her luck being born on an island …” She smiled just a little. “And so Tom, Spear, and I, we ran about like wild things, I guess. We climbed into the Lower City every day it wasn’t raining.” She ran a hand through her tangle of hair. “I loved it there. The rules were different, not so polite, and it was like a whole secret life, something that no one knew about but the three of us. I went with Mémé Annette to Blackpot Market, and Tom and Spear taught Mémé’s son Justin to read, even though he was grown. They felt very important about that. And no one cared that we were Upper City. Maybe because we were young, or Commonwealth, or maybe they’d just gotten used to us. But that last summer before Allemande …” She paused. “That last summer everything changed. Our first day back we scaled the cliff wall. I’d brought grapes from the greenhouses for Mémé …”

She gathered her thoughts, and again the power of his focus was something she could feel on her face.

“Do you remember when the old premier broke the Anti-Technology Pact and lifted the embargo on simple machines, and a mill owner tried to install a waterwheel? How he told the grindstoners he’d sacked that they would be better off without their jobs, because the wheel would lower the price of their bread?”

“You were not in the Lower City during the Grindstoners’ Riot?” he asked.

“The place had gone mad, like looking out a window at a view you see every day, only on this day the glass has warped, or been colored red. It was the place I knew, and then it was not. Tom was nearly killed, would’ve been if Spear hadn’t fought so well. And gendarmes were everywhere, and they were just … hacking at everyone, rioters or no … We had to jump the bodies in the streets. I cut Tom’s and Spear’s hair with a knife behind the weaver’s shop, just so we could get back to the cliffs.”

“What happened to the woman Annette? Mémé?”

Sophia looked up. “She died. The night of the Grindstoners’. How did you know to ask?”

“I heard it. In the way you said her name.”

She nodded. “And within a year there was revolution, the premier was dead, and Allemande was in power. People I’d called friends in the Lower City hated me because I was Upper. And the people I knew from Upper were going to the Tombs, to the Razor, students from the Scholars Hall, our neighbors, Aunt Francesca. They set fire to the chapel with the rook paintings on the walls, on Rue de Triomphe, where Father used to stop and leave coins. Everything was changed.”

It was the sadness that had made her so angry, she supposed. Started her pressure cooker of rage.

“And so that whole first winter of Allemande, while Tom was nursing his leg, I dreamed up outrageous plans to break people out of the Tombs. It kept Tom’s mind from the pain. But Tom said they weren’t bad plans. In fact, he thought one might work, and then I remembered the pieces of the Ancient story, and I wondered exactly what I was doing that was so worthwhile, anyway.”

“And so you did it.”

“We got Aunt Francesca. She’s Mrs. Ellington, now, living up west.”

“And you did it again.”

“And again, and again.”

“And you loved it,” he said.

She looked at her hands, dirty with dust and black powder, and felt the little line appear between her eyes.

“Of course you did what was right,” he said, as if she’d argued. “They were innocents. It was justice. But justice was not the only reason you went back.” He tried to make her look at him, his voice lowering further. “Come, Sophia.” She lifted her gaze. “You loved taking them from the Tombs because you loved the challenge. You loved outwitting the ones who would destroy so much. And you love it now. Tell me I am wrong.”

She bit her lip. She couldn’t tell him he was wrong.

René breathed out a small laugh. “You act as if you have just confessed a crime. Why should you not love it? Do you not think I love snatching artifacts from the hands of the melters? Smuggling them to safety under the very nose of the gendarmes?” He looked down at the Ancient paper in his lap, touching the words “bloodthirsty revolution” behind the glass.

“Have you ever thought,” he said after a moment, “that perhaps … all of this could have happened before? That the people of the Time Before, no matter how weak we think them, that they were only making the mistakes of their ancestors, and that we, in turn, are only making the same mistakes as them? Technology or no? That the time changes but people do not, and so we are never really moving forward, only around a bend? That the world only ever turns in circles. Do you think that could be so?”

She met his gaze, fascinated. “I don’t know,” she said. “But even if that’s true, then don’t you think there is always someone who can change it? Who could break the pattern? Or who could try? If they chose to. Don’t you think that has to be true as well?”

“Yes,” he said, “I do think that.” The tiny fire went out, leaving only the candles. “And I would help you.”

“You are helping me,” she said, voice small. “Isn’t that our agreement?”

“You know that is not what I mean. I would help you.”

She did know. She knew exactly what he meant, and it was loud inside her, like the shattering of glass, like the shifting of the poles, swinging the world into a new alignment. He thought she was someone who could break the pattern of history. And he was offering to break it with her.

And just like that, there were no more questions about games or what was real or whether René Hasard was telling the truth. She just knew he meant what he said. She chose to believe, and with her belief came a pull to him, such an irresistible force, that she wondered if this was how it would feel to be an Ancient satellite, forever circling in the sky. Always kept from flying away by that magnetic draw, always kept from drifting too near by the uncertainties of the atmosphere. She clutched her knees, breathing deep, and breathing deep again, afraid to look at him, this time because she didn’t know what would happen when she did.

Then René said, “I owe you an apology again, Miss Bellamy.”

Her head jerked up. René had gone rigid, expression hard, careful as he set the glass panes back into their crate. He’d completely misinterpreted her silence.

“I have thought of what you said,” he continued, voice still very low, “or what you did not say in Hammond’s kitchen, and I want you to know that I think you are right. This arrangement is … insecure at best, and if another marriage fee can be had, of course you will be obligated. Of course you will do what is needed for your family.”

Sophia stared at him, dumbstruck. Was he really talking about the money? She was sick to death of the money. “I don’t …”

“No. Let me say. We agreed to leave these matters until after the Rook’s mission is done, and it is wrong of me to … to put you in such a position. And the situation, it is … ridiculous, is it not? We do not even know each other.”

They didn’t? In some ways, he seemed to know her better than Tom. “But …”

“Do not concern yourself. You are right. There is no reason to discuss it again.”

The glass with the Ancient fragments had all been replaced inside the box now. He reached out, lifted her hand, and kissed it, a frown on his forehead. She could feel the heat in her face, a pricking sting behind her eyes. If she’d been a satellite before, then maybe this was how it would be to fall through the sky in a blazing ball of fire.

“We should go and help the others. That would be best, no?”

No. No, that would not be best at all. He was setting her hand gently back in her lap, but she did not let go. The frown on his forehead deepened, she opened her mouth to speak, and then the back of her neck prickled, tingling with the pressure of a gaze. Sophia’s head whipped around.

“Spear!”

René sprang to his feet as Spear pushed her bedroom door open a little wider and ducked inside. Sophia stood more slowly, that guilty, uncomfortable feeling in her middle warring with all her newly freed truths. How long had he been standing there? René slid his hands into his pockets, looking at Spear with the blue eyes heavy-lidded.

“When did you get back?” she asked. “I’ve been expecting you.”

“I was on my way to the farmhouse now.” His face was like a metal casting. “I just stopped for … Tom had oil in the sanctuary.” He held out a bundle wrapped in sacking. “I’ve brought you our project.” He’d looked at René when he said it, a particular emphasis on the word “our,” before his cool eyes went back to Sophia.

“They’re done downstairs, Sophie. Don’t you think we should go now …” He nodded toward the dark corridor. “Before you run into someone you shouldn’t?”

LeBlanc stepped carefully around the filth of the street, turned the corner, and was almost immediately confronted by the guard of Allemande. They surrounded their premier, swords drawn, standing at one end of an Upper City boulevard that no longer resembled a boulevard. Barricades that were equal parts scrap wood and pieces of fine furniture had been piled across either end of the block, one of them still ablaze, illuminating the bodies and broken glass that lay on the pavement.

The drawn swords parted, and Allemande stepped through. “Premier,” LeBlanc said. “I have only just arrived. Could I ask for a few moments to assess the situation? And I would prefer to have you wait in my office.”

Allemande’s eyes blinked beneath the glasses, a few of the guards showing surprise.

“For your safety, of course, Premier. I would like to be certain the area is secure.”

“Yes,” said Allemande slowly. He looked about, and then chuckled. “I would like to be present for your interview with the commandant of the Upper City, I think. He has much to answer for. As do you.” The premier put his hands behind his back. When LeBlanc had bowed he strode away with his jangling men, looking a bit like the runt of a litter. A very cunning runt.

LeBlanc watched him go. He had no need of a guard; he was in the hands of Fate. He put his pale eyes on a gendarme standing before a little stone and concrete chapel, unbroken, vibrant red glass showing behind the boarded-up windows. The greatest concentration of the dead were piled before its door, city blue scattered among the other varying colors of cloth. LeBlanc approached cautiously, holding his robes above the blood and muck.

“They tried to take back a chapel, Ministre,” the gendarme said. He was young, voice a little high.

“Are there any live ones?”

“I don’t think so, Ministre. They fought to the last.”

How wise of them, LeBlanc thought. “And who are they?” He looked down at the body in a stained brown shirt near his feet and pushed gingerly with the toe of his shined shoe. The body turned, the man’s eyes wide open and vacant, a gaping sword wound in his chest. Beneath the bloody grime on his face, painted on one of his cheeks, was a red and black feather. LeBlanc looked at the man for a long time, then raised his eyes to the shaking gendarme.