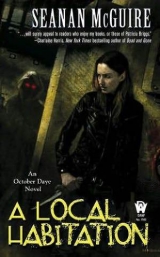

Текст книги "A local habitation"

Автор книги: Seanan McGuire

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

FOURTEEN

“STOP SQUIRMING,” GORDAN SNAPPED, dabbing at my cheek with a cotton swab. She was holding a pair of stainless steel tweezers in her other hand. I eyed them warily. “You’ve got glass ground pretty deep in here. Do you want me to get it out, or do you want to spend the rest of your life looking like an order of meatloaf surprise?”

I glared at her, struggling to hold still. It was turning into a pitched battle between my nerves and the pain. The pain was winning. “That hurts.”

“Suck it up,” Quentin said. Gordan had already treated him, snickering about how much fun it was to watch a pretty boy mop the road with his face. It didn’t seem to have affected her work; she’d sterilized and bound his wounds quickly, even while she was mocking him. He was sitting on the counter, a cup of soup in his hands and a swath of gauze taped across his forehead, pushing his bangs up in a jagged line. He looked like he was recovering from his first bar fight.

I didn’t care; I was just glad he was awake. “Don’t make me come over there.”

“Gordan wouldn’t let you.”

“He’s right for once; I wouldn’t.” She smiled, showing the points of her teeth. “And you should be glad this hurts. The only way it wouldn’thurt is if you were already dead.”

“Just be careful,” I said, hunching my shoulders. I still suspected her; I had no logical reason not to, save for the fact that I couldn’t figure out why she’d have killed her own best friend.

“I am,” she said. She put down the tweezers, selecting a strip of gauze. Her fingers were gentle as she bandaged my cheek, avoiding the spots where the skin was torn. For all her hostility, she knew what she was doing. “You’ll heal, but I don’t recommend sliding down any more driveways on your face.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” I said, dryly.

“Good. This was fun and all, but I don’t want to do it again.” She started to pack the kit with neat, rapid motions, tucking away gauze, ointment, and those awful sharp-edged tweezers. “Get some coffee or something. You look like the dead.”

“The soup’s good,” Quentin said, hefting his mug.

“You’re that worried about my welfare all of a sudden?” I looked at Gordan.

“Stuff it,” she said, not unkindly. “I just don’t want you upsetting Jan even more.”

“Right,” I said, standing and crossing to the coffeemaker. The pot was half– full; good. I didn’t want to bother brewing more. The bandages on my hands were light enough that I could handle it easily—I hadn’t lost any manual dexterity, and that was even better.

We were alone in the cafeteria, and the doors were locked with a warding charm of Jan’s design. I’d tried to open the door once, just out of curiosity, and found myself pushed gently but firmly back into the room. The seal was good. After dropping us off with Gordan, Jan and Terrie had disappeared to find Elliot and take care of the mess blocking the front gate.

“Toby?”

“Yeah?” The coffee was hot enough to be worth drinking. I took a long swallow and topped the cup off again. I was sure to need the caffeine.

“What are they going to do with the car?”

“Small questions, small minds,” Gordan muttered.

Ignoring her, I said, “Well, either they’re going to put up a really bigillusion while they search for a giant can opener—”

“Yeah, right,” Quentin said, wrinkling his nose. Gordan snorted.

I settled next to him. “Like I said, either it’s giant can opener time, or they’ve got themselves a forklift.” My poor car.

“Will they call the cops?”

Gordan snorted again as I said, “Jan’s not going to call the police when she has a basement full of bodies.” That was good, since none of us wanted to be arrested for murder or carted off for dissection by the nice government men. That’s the kind of hospitality I can skip.

“Oh.” Quentin considered this. “What about our stuff?”

“Fireballs aren’t generally polite enough to leave everyone’s spare jeans intact.”

He sighed. “Great.”

“I know this is hard for you,” I said, fighting to keep from smiling, “but human teenagers wear the same clothes two days in a row all the time and it hasn’t killed any of them yet.” Quentin was doing the impossible: he was cheering me up. Well, him and the coffee.

Quentin wadded up his napkin and threw it at me. “Jerk.”

“Completely,” I said. “Besides. I spoke to Sylvester, and he said he was going to send someone to help.” And to take Quentin back to Shadowed Hills, although that could wait until he wasn’t still riding the adrenaline high of his very first auto accident. “So whoever it is, they’ll have a car, and they can get you some fresh clothes.”

“That won’t make trouble with Duchess Riordan?”

“Kid, at this point, she can cope.”

Gordan glared, opening her mouth. Whatever she was going to say was lost as the wards dissolved and the door swung open, letting Jan, Elliot, and Terrie into the room. Jan’s shoulders were squared and her chin was up; she looked like every other hero in Faerie, getting ready to strap on her shining armor and ride off to fight the dragon. That might be a problem, because the world has changed, and the heroes haven’t. Oh, they’re still the perfect solution when you’re dealing with dragons or damsels in distress—I figure that’s why Faerie keeps making heroes—but there’s a distinct shortage of problems that straightforward. Giants and witches, fairy-tale monsters . . . those are for heroes. For everything else, they have people like me.

All of us, even Gordan and Quentin, fell silent as we watched Jan walk to the coffeepot and fill a large mug, draining it dry before she turned toward me. Elliot tapped the top of the machine, which promptly started refilling the pot. Hearth magic has its uses, even if I couldn’t quite see how “making magic coffee” fell under the usual Bannick suite of abilities.

“So you think it’s one of us,” Jan said, without preamble.

How far can we push you before you snap, little hero?I wondered. Aloud, I said, “It’s the only answer that makes sense.” I felt Gordan’s glare on the back of my neck. Sorry, kid. Sometimes you have to tell the truth, even when you’re talking to heroes. Maybe especially when you’re talking to heroes.

Jan’s expression was bitter. I’ve seen that mixture of resignation and hopelessness before; it’s usually in my mirror. “You’re sure?”

“As sure as I can be.” I stood. I knew I was falling into a subservient posture, but I couldn’t help it. Half of me is fae, and the fae know how to obey their lords. “Monsters don’t lay that kind of trap.”

“I see.” She looked down at her hands. Her nails were bitten to the quick. “I trust everyone that works for me. I can’t imagine who would do this.”

What was I supposed to say? I exchanged a glance with Quentin. Jan built herself an ivory tower to keep the wolves out; she never dreamed they were already inside.

“I’m sorry,” I said. I meant it: no matter how much of an idiot she’d been, none of them deserved this. “We’ll do what we can.”

“I know.”

“And we’ll figure out what to do about the bodies.” I shook my head. “I still don’t understand what’s going on with them.”

“The night-haunts always come,” said Quentin.

“Maybe they aren’t really dead.” Jan looked at me, suddenly hopeful. “Can you bring them back? Wake them up?”

“No.” I didn’t know how to tell her how dead they really were. Jan hadn’t tried riding their blood; she hadn’t tasted the absence of life like sour wine. Quentin and I did, and we knew they were gone. Worse than gone: their blood was empty. Blood is never empty. It remembers all the little triumphs and tragedies of a lifetime, and it keeps them for as long as it continues to exist. Their blood remembered nothing. Whatever lives they’d lived and whoever they’d been, it was lost when they died. They took it into the darkness with them, out of Faerie forever.

Jan sighed. “I see. I . . . oak and ash, Toby, I’m sorry. You should never have gotten wrapped up in all of this.”

“My liege sent me, so I came.” I shrugged. “I’m not leaving until this is over.”

“And Quentin?” asked Terrie, biting her lip.

Quentin shot me a worried look. Clearly, he’d been wondering the same thing.

It was going to come out eventually. “Sylvester is sending someone to get him. Until then, we just need to keep him safe.”

“Toby—”

“She’s right,” said Terrie. “This isn’t your fight, Quentin. You don’t have to stay.”

“I want to,” he said.

“Hey, I say we let him,” said Gordan. “At least if the killer picks him, we get to live a little longer. Call it a learning experience.” You have to respect self-interest that focused. Most people at least try to pretend your welfare matters as much as their own.

“Gordan, that isn’t fair,” said Jan.

“Fair isn’t the point, and this isn’t a discussion. Sylvester’s calling him home. He’s going,” I said. Quentin’s expression was one of sheer betrayal. Tough. I wasn’t going to be responsible for getting him killed. “I’ll be here until this is over. You can’t get rid of me that easily.”

“I don’t think anyone ever has,” Gordan muttered. She’d given up glaring: now she just looked sullen.

“In the meantime,” I said, ignoring her, “we’re going to need all the things I asked for. The information on the victims, access to their work spaces, everything. I don’t want any of you going anywhere alone. Is it possible for you to go somewhere else in the County until this is fixed? Someplace outside the knowe?”

Jan shook her head. “No.”

“Jan—”

“April can’t leave.” The words were simple, quietly said, and utterly without hope. “I don’t have a portable server set up for her. If we went, we’d have to leave her behind. She’d be defenseless. I won’t leave my daughter.”

“And we won’t leave our liege,” said Elliot.

“If everyone dies, you lose the County. Let me call Sylvester. Let him help.”

“Dreamer’s Glass will see it as a threat.”

I eyed Jan. “Is there anyway for us to get help without going to war?”

“No,” she said, simply. “There isn’t.”

“Maybe that’s what they want.” Gordan stood, crossing her arms over her chest. “How do we know Sylvester sent them? Maybe they’re here to make surewe don’t figure things out.”

“Gordan—” Jan began, and stopped, glancing toward me. They didn’t know. With the lines down between them and Shadowed Hills, there was no way they could. Much as I was coming to dislike her, I almost had to admire the way Gordan’s mind worked. She wanted us out, and she’d found one of the fastest ways to get what she wanted: calling our credentials into question. She was smirking now, visibly pleased.

“That’s crap,” snapped Quentin.

“He’s right,” I said. “If you want to work yourselves into a paranoid frenzy, go for it. Whatever. Just understand that it’s not my damn problem. The dead are my problem.”

Elliot had the grace to look embarrassed. “I’m sorry. It’s just that politically . . .”

“Politically, it would be a good idea to send saboteurs. We’re not them.”

“I believe you,” said Jan. Behind her, Gordan scowled.

“Good.” I walked to the coffee machine, aware of the eyes on my back. Let them stare. I needed to regroup before I started screaming at them. I’d been trying to ignore the political aspects, but they still mattered. No one should die for land. Oberon believed that: he fought to keep the playing field even. Some people say that’s why he disappeared—he saw what Faerie was becoming and couldn’t bear to watch. I wasn’t sure I could bear it, either. I didn’t have a choice.

“One way or another, I guess we’ll know your motives soon,” said Terrie.

I toasted her with my coffee cup. “Same to you.”

“We know the risks,” said Jan. Before the fae grew soft and secretive, the look in her eyes would have sent armies to die. There’s no stopping that kind of look; all you can do is stand back and hope the casualties will be light. “So where do we go from here?”

I met her eyes, and sighed. She wasn’t going to back down; we both knew it. The people that were going to leave were already gone, leaving only the loyal ones, the heroes, and the murderer. I’m not a hero; if I’m lucky, I never will be. I just do my job.

“You’re going to have to do everything I say,” I said.

“Of course,” she said, and smiled. It was a victor’s smile, and she was right to smile that way. We were staying at ALH, and they were counting on me to win their war. I just didn’t see a single way to do it.

FIFTEEN

“ANY ANSWER?”

A “None.” Quentin dropped the phone back into the cradle, looking disgusted. “I’ve tried calling eight times, and no one’s picking up.”

“Sylvester said he’d keep someone by the phone. So we’ve got two choices. Either he forgot . . .”

Quentin snorted.

“My thoughts exactly. Which means something’s stopping the calls from going through. How much do you know about the phones at Shadowed Hills?”

Quentin shrugged, putting down the folder he’d been pretending to read. “They’re ALH manufacture. They were installed shortly before I was fostered with Duke Torquill.”

“Uh-huh. Ever had any problems with them?”

“No. Never.”

“But no one’s picking up, and none of Jan’s messages got through, even though we were able to call just fine from the hotel.” A nasty image was starting to form in my mind. “Give me the phone.”

“What?”

“Give me the phone.” I held out my hand. “And keep reading. We need to know whatever there is to know about these people.”

“I don’t understand why I have to do this,” he grumbled, handing me the receiver. “You’re making me go home.”

“Because I said so. Now shut up, and read.” Half-holding my breath, I punched in the number for the Japanese Tea Gardens, and waited. Shadowed Hills was a knowe. Shadowed Hills had a Summerlands– based phone system. The Tea Gardens . . . didn’t.

After our discussion in the cafeteria, Elliot had taken us to what had been Colin’s office, where I could get started on the investigative side of things while keeping Quentin out of trouble. It was a small, boxy room, with surfing posters on the walls and Happy Meal toys cluttering the shelves. The single window looked out on an improbably perfect, moonlit beach. That was a Selkie for you. He’d found a way to work inland and still be close to home.

We searched the office thoroughly, but found nothing to justify murdering the man. There was a small Ziploc bag of marijuana behind the fish tank, and a large collection of nudie magazines which caused Quentin to forget he was mad at me for almost ten minutes while he snickered. A herd of miniature Hippocampi swam from side to side in the tank, eyeing us suspiciously. The largest was no more than eight inches long, a stallion whose perfect equine upper half melded seamlessly into the scales and fins of his bright blue tail. His mares came in half a dozen colors, as brilliantly patterned as tropical fish.

The phone kept ringing. I sighed, and was about to hang up. There was a clatter and a shout of, “Dammit!” as the receiver was slapped out of the cradle on the other end. Breathless, Marcia said, “Hello?”

“Marcia?”

“Toby? Oh, thank Oberon. I found Tybalt for you. He’s—”

“Marcia, I don’t have time for this right now. I need you to do me a favor, okay? I need you to go to Shadowed Hills, and tell Sylvester I need help. I’m in Fremont, and there’s something wrong with the phones here. I can’t call Shadowed Hills.”

“Fascinating. Do go on.” The voice was dry, amused, and distinctly notMarcia’s.

I paused. “Tybalt?”

“Did you expect that you would call for me, and I would refuse? Perhaps you did. Much as I appreciate your deciding to provide me with an afternoon’s amusement, I must say . . . ‘here, kitty, kitty’? Did you really expect this to have any positive result?”

“Tybalt, this is really not the time.”

“What did you want to discuss with me that was so vital you had to send a handmaid begging at the bushes?” His tone sharpened, turning dangerous. “I don’t take kindly to being toyed with.”

I rubbed my forehead with one hand. “All right, look, my methods were maybe not the best, but they got you to wait on my call, didn’t they? I’m guessing you didn’t do anything to Marcia?”

“She assured me her activities were entirely your fault.”

“Good.” Quentin was giving me a quizzical look. I turned away from him before he could distract me, and said, “Did she tell you why I’m in Fremont?”

“No. I assume that honor was being left for you. I do hope you’re giving my counterpart the troubles you normally reserve for me.”

Oh, oak and ash. That was what I’d been hoping not to hear. Keeping my tone light, I said, “Your counterpart. I assume you mean Barbara Lynch, the local Queen of Cats?”

“None other.” The danger bled out of his voice, replaced by amusement. “She must not know you’ve elected to phone me. We’re not precisely on good terms, she and I. Silly little thing should never have taken a throne. Why, with her delicate sensibilities—”

“She’s dead, Tybalt.”

Silence.

“She died last month.”

Now he spoke, voice a low, harsh rasp that was closer to a snarl: “How?”

“We don’t know. That’s the problem.” I closed my eyes. “You didn’t know.”

“How would I have known?” The bitterness and anger in his tone were undisguised. “She held a crown without a kingdom, thanks to that Riordan bitch.”

That was new information. “What do you mean, ‘a crown without a kingdom’?”

“There were no true Cait Sidhe in her domain, only our feline cousins and their changeling children. The others left long ago, when it became clear that Riordan held no respect for Oberon’s word.”

Oberon established the Court of Cats, gave them a political structure outside the standard Faerie Courts and Kingdoms. They ruled themselves, and no political power in Faerie had any say over them. There have always been rulers who didn’t want to listen to that ancient declaration. They try to tax the Cait Sidhe, subvert them, recruit them into their political reindeer games. It wasn’t much of a surprise to hear that Riordan was one of those.

Still . . . “You can talk to my cats.”

“Your cats are my subjects, and subject to my laws. The cats of Barbara’s Court weren’t. They couldn’t reach me.”

“Where did all the other Cait Sidhe go?”

“My fiefdom. Others. But Barbara remained, stubborn to the end.” His tone turned more bitter still. “I think she liked the perversity of it. Bowing at the knee to a daughter of Titania.”

“She’s not bowing anymore,” I said, with a sigh. “I’m sorry to be the one who told you. And I’m sorry about the ‘here kitty, kitty’ thing. It just seemed like the best . . .”

“Wait. She died in Fremont, and you don’t know what killed her.”

“Yes.”

“And you’re still there.”

“Yes.”

“Are you in danger?”

I considered lying. Only for a few seconds, but still, the urge was there. Pulling his jacket closer around me, I said, “People are dying. Sylvester’s sending someone to get Quentin out, but I’m staying until we know what’s going on. I can’t run out on them.”

Again, silence.

“Tybalt?”

“You really are a little fool, aren’t you?” His tone was distant, almost reflective. “You still have the jacket I left with you?”

“I do,” I admitted.

“Good. I’ll be wanting it back.”

“I’ll try to stay alive long enough to return it. Can you put Marcia on? I need to ask her for a favor.”

His tone sharpened. “What favor?”

“Something’s wrong with the phones, and I can’t get through to Shadowed Hills. Someone needs to tell Sylvester we’re in trouble. Big trouble. Someone just tried to kill us, and they came pretty close to succeeding.” I paused. “He can probably call me from the pay phone in the parking lot. He should station someone there.”

“Consider the message relayed,” said Tybalt, in that same distant, thoughtful tone.

“What are you—”

The phone buzzed in my ear. The line was dead; he’d hung up on me.

Groaning, I turned and dropped the receiver back into the cradle. “Whatever’s wrong with the phones, it’s specific to Shadowed Hills. I got through to the Tea Gardens just fine.”

Quentin was once more pretending to review the employee files. He slanted a sidelong look my way, and asked, “What did Tybalt want?”

“To give me a headache. Still, he wouldn’t take the message if he wasn’t planning to deliver it.” I leaned over to take the folder from his hands, scanning the first page, and wrinkled my nose. Maybe the company dietitian cared about the fact that Barbara liked her field mice alive, but I didn’t. “Change of subjects. Does it say anything in here about where her office is?”

“Nope. Did you know that Colin had a doctorate in philosophy?”

I looked up. “What year, and where from?”

“Nineteen sixty-two. Newfoundland.”

“Any of the others have degrees from Canadian colleges?” I flipped through Barbara’s folder, stopping at the sheet labeled “education.” “Babs didn’t—her degree’s from UC Berkeley. Women’s Studies and English.”

“Peter taught History at Butler University in Indianapolis, and Yui’s file says she used to be a courtesan in the court of King Gilad.”

I looked up again, eyeing Quentin. “ Pleasetell me you know what that means.” He turned red. “Good. I didn’t want to explain it. So we have basically no connections.”

“None.”

“And of the four victims, two have offices that don’t seem to exist.” We’d done Peter’s office before Colin’s. It was almost empty, containing a desk and an assortment of office supplies. The few personal touches we found dealt with football—a Butler University pennant on one wall and a foam– rubber football that he probably tossed around when he was bored. There was nothing that provided us with a visible motive for murder, and that worried me.

“One at least—I mean, no one’s actually said Barbara had an office.”

“Right.” I dropped myself into the chair by the fish tank. The Hippocampi fled to the far end, the tiny stallion swimming back and forth in front of the rest as he “protected” them from me. “Maybe she worked out of a broom closet, I don’t know. No offices means no leads. Not that we’re getting much from this place unless you like weed.”

“What?”

“Never mind.” I shook my head. “So they were telling the truth about the turnover rates. It doesn’t look like they’d lost an employee in a long time before this started.”

“So where does that leave us?”

“It leaves ‘us’ nowhere, Quentin. You’re leaving as soon as your ride gets here.”

“And what if I won’t go?” He crossed his arms, jaw set.

“Sylvester’s orders, kid. You’ll go.”

“Why are you so determined to get me out of here? I want to help. I want to—”

I grabbed the collar of my shirt and pulled it down, exposing the scar on my left shoulder. Quentin stopped talking, and gaped. I held the collar down long enough to make sure he got a good look before tugging it back into place, glaring at him.

“That was made with iron.” His eyes were wide, and scared.

“Good to see they’ve taught you what iron damage looks like.”

“How did you—”

“I lived because I got lucky, and because someone was willing to pay a lot to keep me around a little bit longer. Most people don’t get lucky.”

He swallowed, and stood. “I’m going to feed the Hippocampi.”

“Good idea,” I said, and reached for the stack of folders. I didn’t want to scare him—he was making more of an effort to do the right thing than most purebloods twice his age would bother with—but he needed to realize that this wasn’t a game. This was real, and he was going home.

The Hippocampus food was on the shelf beneath the fish tank. Giving me one last sidelong glance, Quentin opened it, shaking bits of dried kelp and barley into the water. The tiny horses flocked to the food, their wariness forgotten as they chased it around the tank. I smiled faintly and flipped the first folder open.

They liked records at ALH: everything from employment history to diet and heritage was recorded, like they were trying to paint portraits of their employees on paper. Even though was it helping us research, I couldn’t figure out why they’d bothered in the first place.

The first page of Colin’s file included a listing of family members. I found myself wondering who was going to have to tell them he was gone. Disgusted by the thought, I slammed the folder down on the desk and pushed it away. “This isn’t helping.”

Quentin looked up from feeding the Hippocampi. “What do you mean?”

“They were normal.” I indicated the folder. “All were purebloods less than three hundred years old, all lived human at some point without cutting their ties to the Summerlands—nothing out of the ordinary. Barbara was local, and Yui was from Oregon, so there’s a West Coast pattern . . . only Colin was from Newfoundland, and Peter’s last listed residence was in Indiana.”

“So what connects them?” Quentin asked, returning the Hippocampus food to the shelf where he’d found it.

He was obviously expecting some ingenious, Sherlock Holmes-like gem of wisdom, and I hated to disappoint him. Unfortunately, I had no other options. “Nothing but ALH.” That worried me. Unless our killer was basing his moves on a factor I couldn’t see, we were dealing with someone whose only motive was “here.” That didn’t bode well. For one thing, it was a strong indicator that we might be looking for a crazy person.

Insanity is dangerous. All fae living in the mortal world are at least a little nuts; it’s a natural consequence of being what we are. We have to convince ourselves that we can function in a place that’s run by people whose logic looks nothing like our own. When we do it well enough, we’re even right. The problem is that eventually, the lies stop working, and by that point, it’s generally too late to run.

“Oh,” said Quentin, sounding disappointed.

“Yeah,” I agreed, “oh.”

Something crackled in the air behind me. I didn’t pause to think; I just whirled, scattering file folders in my rush to put myself between Quentin and any potential threats. April’s outline flickered as the papers passed through her, fluttering to the floor. She watched impassively as they fell, finally asking, “Are you well?”

“Don’t dothat!” I said, dropping shakily back into my seat. Quentin looked as shocked as I felt. Good. That made him less likely to laugh at me later.

“Why not?” She tilted her head, showing a flicker of curiosity. The fact that I’d just thrown several sheets of paper through her upper torso didn’t seem to bother her. Dryads are weird, but April was going for the grand prize.

“Because it’s not polite to startle people.”

“I see.” April looked to Quentin. “Is she correct?”

Wordlessly, he nodded.

“I see,” April repeated. After a moment’s consideration, she asked, “Is it my materialization you object to, or my doing so outside your immediate range of vision?”

Quentin and I stared at her. She gazed back, bland curiosity in her yellow eyes. Now that I was looking more closely, I could see that her irises lacked normal variation; they looked almost painted-on. Her lack of small detail was making her seem more and more like something that was created, not born. That probably explained a lot about her, even if it didn’t change the fact that she’d just tripled my heart rate by deciding not to use the door like everybody else.

“I object to having you appear behind me without warning,” I said.

Quentin nodded. “That’s, um, pretty much my problem, too.”

April smiled, an expression that looked entirely artificial. “Acceptable. I will refrain from abrupt materialization in your immediate vicinity without prior notification of my arrival.”

It took me a moment to puzzle through that one. “So you won’t appear suddenly?” I guessed. I wasn’t going to make assumptions with someone who seemed to view silly things like “physics” as a mere convenience.

“Yes.”

“Good.” I glanced back toward Quentin, and saw that he was starting to relax again. “Can I help you with something?”

“Mother says you are going to assist us.”

“We’re going to try.”

“Mother says you are here about the disconnection of the residents of this network.”

Silence was becoming a major punctuation in this conversation. I looked to Quentin, who shook his head and spread his hands to show that he hadn’t understood it either. “What?”

“The ones that have gone off– line. You will determine what has caused them to remain isolated from the network.”

Oh. She was talking about the murders. “Yes. We’re going to find out why people are being killed.”

She frowned, looking puzzled. Then the expression faded, and she asked, “Why?”

I shrugged. “Somebody has to.”

“That makes no sense,” she said, frowning again.

“I rarely do. It’s one of my best traits.”

Quentin snorted, trying not to laugh.

“Gordan does not trust you,” April said.

“I knew that, actually.”

“Mother trusts you.” She shook her head. “I still do not know whether I trust you.”

“I’m glad you can be honest about that,” I said. She was starting to unnerve me. There were too many little inconsistencies in the way she behaved and the way she was made, and it was getting harder to resist the urge to wave my hand through the space her body appeared to occupy just to find out whether or not she was there.

“Honesty is the only sensible option.”

Maybe for computer-powered Dryads, but the rest of Faerie seemed to be having a bit more of a problem with it. Slowly, I asked, “Why are you here?”

“Mother requested that I notify you if any company personnel exited the presence of their assigned partners.”

“And?”

“Gordan and Terrie have departed from one another’s company.”

Swell. “Message received. Where are they?”

“Gordan is located in her cubicle. Terrie is located in the cafeteria.”

“All right. Why don’t you go take care of whatever else you need to do, and I’ll see if I can explain to them why this isn’t okay, all right?”

April gave me a long, measuring look, expression alien as ever. It was like watching an anthropologist trying to figure out a foreign culture—and who knows? Maybe that’s what she was doing. “Understood,” she said finally, and vanished in a flicker of static and ozone.

“Right,” I said, eyeing the space where she’d been before turning to pull the keys out of my pocket and toss them to Quentin. He caught them without pausing to think; good reflexes.

He gave me a bewildered look. “What are you giving me these for?”

“I need to go knock some heads together. Repeatedly. I want you to lock yourself in.”

“Uh.” Quentin’s eyebrows rose, expression turning dubious. “Have you never seen a horror movie in your entire life? Splitting the party is never a good idea.”