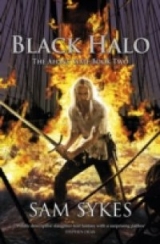

Текст книги "Black Halo"

Автор книги: Sam Sykes

Соавторы: Sam Sykes

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 41 страниц)

Asper opened her mouth to retort, but found precious little to say by way of refuting the accusation, and even less to say to pull her hand back.

‘I suppose,’ she said, pressing her back up against the shict’s again. ‘It can be a frightening thing, combat.’

‘But you don’t run,’ Kataria continued. ‘You don’t back away.’

‘Neither do you,’ Asper replied.

‘Well, obviously. But it’s different with me. I know how to fight. If I cankill it, and I usually can, I do kill it. If I can’t kill it, and sometimes I can’t, I run away until I cankill it and then I come back, shoot it in the face, tear off its face and then wear its face as a hat … if I can.’

‘Uh …’

‘But you,’ Kataria said, her body trembling. ‘ Youlook so terrified, so uncertain … and really, sometimes, I’m uncertain when the fight breaks out. I don’t know if you’ll make it out of this one or that one and I expect you to run. I would, were I you.’

‘But,’ Asper said softly, ‘you’re not.’

‘No, I’m not. I don’t stick around if it’s not certain.’ The shict leaned back, sighing. ‘It was all certain when I left the forest to follow Lenk, you know? I knew I couldn’t stay there because I didn’t know what was going to happen. But everyone knows what a monkey will do. Even one with silver fur just fights, screams, hoards gold and tries to convince himself he’s not a monkey.’

‘Fighting, screaming and hoarding gold is all we’ve done since we left on the Riptide,’ Asper said. ‘Come to think of it, it’s all we’ve done since I met you.’

‘So why doesn’t it make senseanymore,’ Kataria all but moaned as she slumped against the priestess’ back. ‘This was all so much funwhen we started. But now we’re just sitting around in furs, talkinginstead of killing people.’

‘And … that’s bad?’ Asper asked. ‘I’m sorry, I really can’t tell with you.’

‘That’s bad,’ Kataria confirmed. ‘I should be running.’

‘But you’re not.’

‘And whyam I not? Why don’t yourun when you feel like it?’ The shict scratched herself contemplatively. ‘Duty?’

She swallowed the question, and Asper wondered if Kataria could feel her own tension as it plummeted down to rest like an iron weight in her belly. Why didshe stay? she wondered. Certainly not to protect her friends. I need it more than they do. To survive, then? Maybe, but why get involved at all with them, then?Duty?

That must be it.

Yeah, she told herself, that’s it. Duty to the Healer. That’s why you fight … that’s why you kill. It’s certainly not because you’ve got an arm that kills people that you can’t possibly run away from. No, it’s duty. Tell her that. Tell her it’s duty and she’ll say ‘oh’ and leave and then there will be two people who hate themselves and don’t have answers and you won’t be alone anymore.

‘Is it your god?’ Kataria asked, snapping the priestess from her reverie. ‘Does he command you to stay and fight?’

‘Not exactly,’ Asper replied hesitantly, the question settling uneasily on her ears. ‘He asks that we heal the wounded and comfort the despairing. I suppose being on the battlefield lends itself well to that practice, no?’

Is that it, then? Are you meant to be here to help people? That’s why you joined with them, isn’t it? But then … why do you have the arm?

‘You have your own god, don’t you?’ Asper asked, if only to keep out of her own head. ‘A goddess, anyway.’

‘Riffid, yeah,’ Kataria replied. ‘But Riffid doesn’t ask, Riffid doesn’t command, Riffid doesn’t give. She made the shicts and gave us instinct and that’s it. We live or die by those instincts.’

And what of a god who gives you a curse?Asper asked herself. Does he love or hate you, then?

‘So we don’t have signs or omens or whatever. And I’ve never looked for them before,’ Kataria continued with a sigh. ‘I’ve never needed to. Instinct has told me whether I could or I couldn’t. I’ve never had to look for a different answer.’

Is there a different answer? What else could there be, though? How many ways can you interpret a curse such as this? How many ways can you ask a god to explain why he made you able to kill, toremove people completely, to your satisfaction?

‘So … how do you do it?’

It took a moment for Asper to realise she had just been asked a question. ‘Do what?’

‘Know,’ Kataria replied. ‘How do you know what’s supposed to happen if nothing tells you?’

How would a woman of faith know if her god doesn’t tell her?

‘I suppose,’ Asper whispered softly, ‘you just keep asking until someone answers.’

‘That’s what I’m tryingto do,’ Kataria said, pressing against Asper’s back as she pressed her question. ‘But you’re not answering. What do I do?’

‘About your instincts?’

‘About Lenk, stupid!’

‘Oh,’ Asper said, blanching. ‘Ew.’

‘Ew?’

‘Well … yeah,’ Asper replied. ‘What about him? Do you like him or some-’

The question was suddenly bludgeoned from her mouth into a senseless cry of pain as something heavy cracked against her head. She cast a scowl over her shoulder to see Kataria resting the gohmn leg gently in her lap, not offering so much as a shrug in excuse.

‘Did … did you just hit me with a roach leg?’ the priestess demanded, rubbing her head.

‘Yeah, I guess.’

‘ Whydid you just hit me with a roach leg?’

‘You were about to ask something dangerous,’ Kataria replied casually. ‘Shicts share an instinctual rapport with one another. We instantly know what’s acceptable and unacceptable to speak about.’

‘I’m human!’

‘Hence the leg.’

‘So you’ve graduated from insults to physical assault and you expect me to sit here and listen to whatever lunacy you spew out? What happens next, then? Don’t tell me.’ She started to rise again. ‘How many times have youbeen hit in the head today?’

Kataria’s grip was weak, her voice soft when she took Asper by the wrist and spoke. Asper could feel the tension in her body slacken, as though something inside her had clenched to the point of snapping. It was this that made the priestess hesitate.

‘I’m asking you to listen,’ the shict whispered, ‘so that I don’t find out what happens next.’

Uncertain as to whether that was a threat or not, Asper settled back into her seat and tried to ignore the feeling of the shict’s tension.

‘The thing is, we’re not even supposed to talkto humans,’ Kataria explained. ‘We only learn your language so we can know what you’re plotting next. Originally, I thought that being amongst your kind would be a good way to find that out.’ She sighed. ‘Of course, within a week, it became clear that no one really had anything all that interesting going on in their head.’

Asper nodded; an insult to her entire race was slightly more tolerable than an insult to her person, at least.

‘I should have run, then,’ Kataria said. ‘I should be running now … Why am I not?’

‘Is it’ – Asper winced, bracing for another blow – ‘just Lenk that’s keeping you here?’

‘I protected him today,’ the shict said, a weak chuckle clawing its way out of her mouth. ‘He was going into one of his fits, so I stepped forward and did the talking. I protecteda human.’

‘You’ve done that before, haven’t you?’

‘I’ve killed something that might have killed a human before, but I never did … whatever it was I did,’ Kataria said. ‘He just needed help and I …’

‘Uh-huh,’ Asper said after the shict’s voice had trailed off. ‘And you did it because of his … fits did you call them?’

‘Have you noticed them?’

Asper closed her eyes, drawing in a deep breath. She wondered if Kataria could feel her tension growing, if she could feel the chill racking her body.

Fits, she thought to herself. I have noticed no fits. I have noticed what Denaos whispers, how he accuses Lenk of going mad, slowly. I have noticed the emptiness of Lenk’s eyes, the death in his voice, the words he spoke.

‘Tell me,’ Asper said softly, the words finding their way to her lips of their own accord. ‘Do you listen to your instincts?’

‘Of course.’

‘Even when they tell you something you don’t want to hear?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Let’s talk about Lenk for a moment.’

‘All right,’ Kataria replied hesitantly.

‘We don’t know where he came from aside from a village no one’s heard of, we don’t know who his parents are, what his lineage is or even where he got his sword.’

‘That’s not fair,’ Kataria protested. ‘Even hedoesn’t know that.’

‘And does he know who taught him to fight?’

‘What?’

‘I learned from the priests, Dreadaeleon was taught by his master, even Denaos likely learned all that he knows from someone,’ Asper pressed. ‘Who taught you to fire a bow? To track?’

Kataria’s body tensed up again, the kind of nervous tension that Asper had felt many times before. Uncertainty, doubt, fear. It ached more than she thought it might to put Kataria through them. But her duty, too, was clearer than she thought it might be.

‘My mother,’ Kataria said. ‘But what-?’

‘Have you ever known,’ Asper spoke silently, ‘anyone who fights, who kills as naturally as Lenk does?’ At Kataria’s silence, she pressed her back against her. ‘Have you seen him after he kills?’

Her question was not delivered with the cold, calculating tone she thought would be befitting. It was choked, quavering, but she could hardly help it. The realisations were only coming to her now, with swift and sudden horror. But perhaps that wasn’t so bad, she reasoned; perhaps Kataria would be comforted to know someone shared her plight, someone that was trying to help her.

And she wouldhelp the shict, she resolved. Helping people, regardless of what kind of people they were. That was why she had taken her oaths.

‘I … I have,’ Kataria replied with such hesitation that Asper knew the same images filled her head.

‘I’ve seen everyone kill,’ Asper whispered. ‘I forced myself to, to know how it was done, if … if I ever had to. Denaos boasts, you exult, Dreadaeleon pauses to breathe, even Gariath took the time to snort. But Lenk … does nothing. He says nothing, he doesn’t react, but he looks … he looks …’ The dread came off her tongue. ‘Satisfied. Whole.’

She could feel Kataria tremble, or perhaps that was herself, for she frightened herself as much as she tried to frighten her companion. But perhaps both of them needed to be frightened, she reasoned, both of them needed to be scared in the face of this new realisation that, in the absence of any demon or longface, Lenk might be the greatest threat.

‘Who looks like that?’ she asked. ‘What would make a man act like that?’

Trauma? Madness? Something else? Whatever plagued him, whatever threatened him, threatened them all, Asper knew. And as she felt Kataria tremble, felt her go limp against her back, she knew her friend knew it as well.

‘Your instincts were confused,’ Asper said softly. ‘You wanted to run, as would anyone, but you want to help and only a few can say they would want that.’

But in this knowledge, Asper found peace, as demented as it sounded to her. In Kataria’s sinking body, she found the urge to rise up. In her friend’s suffering, she found a strength that allowed her to reach down and take Kataria’s hand in her own, a strength that would carry her to the peace the priestess felt, a strength that would carry Lenk.

This was her purpose, her duty.

‘And we will help him,’ Asper said, giving her hand a gentle squeeze. ‘It’s not gods or instinct that make us do it.’

‘Then what is it?’ Kataria asked, her voice weak.

‘You,’ Asper said gently. ‘You will do it, because you’re in love.’

This was the moment she lived for, the moment that had been far too rare in coming lately. The face of a child told they would walk again, the exasperated gasp of a moments-old mother told their infant was healthy, the solemn nod and sad smile of a widow who heard the blessings said over her husband’s grave.

And now, she thought, the embrace between races supposed to be enemies, the long road to helping a friend recover.

This was it.

This was her purpose.

This was why.

She released Kataria’s hand and turned around. Her companion did not, at first, but she waited patiently. It would come slowly, with great difficulty. It always did, but the reward was always greater in coming. And so she waited, watching as Kataria tensed, as Kataria clutched the gohmn leg in trembling fingers, smiling.

She continued to smile.

Right up until the leg lashed out and caught her in the face with such force as to snap her head to the side.

‘Wh-what?’ she asked, recovering from the blow with a hand on an astonished expression. ‘I didn’t mean to say-’

‘I’m not.’

The leg whipped out again, struck her in the side with more force than a leg should be able.

‘Okay, you’re not, but-’

‘I’m not.’

Again it lashed out, found her elbow. It snapped, leaving a red mark upon Asper’s flesh covered by the stain of its basting juice. She didn’t even have time to form a reply before Kataria whirled, hurling what remained of the leg at her.

‘I’m not.’

She lunged, took Asper by the shoulders and hurled her to the earth. No anger in her face, no sadness, no tears. Nothing but something cold and stony loomed over her, a face as hard as the fist that came down and cracked upon her cheek.

‘I’m not, I’m not, I’m not, I’m not, I’m not, I’m not, I’m not-’

No protests from Asper, no denial but for the feeble defence she tried to muster, raising her hands to protect her face, futilely, as the shict blindly lashed out and struck her over and over, once for each word, each kiss of fist to face a confirmation, each bruise that blossomed a reality.

And then, it stopped, without gloating, without a reason, without even a noise. Asper heard the shict flee, heard her running with all the desperation one flees for their life with.

The sound faded into nothingness. The trees whispered as the sun began to set behind them. In the distance, toward the village, a whoop of celebration rose. Their feast was starting.

She should rise, she knew, and go to it. She should rise, even though her body was racked with pain. She should go, even though her legs felt dead and useless beneath her. She should see the others, even though her eyes were filled with tears. She should see them, they who had beaten her, lied to her, disparaged her faith and tried to throttle her.

She should.

But she could not think of a reason why.

ACT THREE

Feast among the Bones

Twenty-Six

WHISPERS IN DARK PLACES

The Aeons’ Gate

The Island of Teji

Fall, early … maybe?

Of my grandfather, I don’t remember much. Of my father, even less. He was a farmer, a quiet man, always tithed. Even as I’m able to remember more here on Teji, that’s roughly all I recall.

Well, that’s not entirely true. I do remember what he said to me, once.

‘ There are two kinds of men in this world: those who live with war and those who can’t live without it. We can live without it. We can live a long time.’

I remember he died in fire.

I had always wanted to believe I could live without war. Even after I picked up my grandfather’s sword, I wanted to know of a time when I could put it down again. I had always wanted to say that this part of my life was something I did to survive and nothing more. I wanted to be able to tell my children that we could live without war.

I wanted children.

And for the past few days, I was certain I would have them and that I could tell them that.

Maybe I was wrong. Maybe father was wrong.

I tried. I really did. Khetashe knows how I did, how I tried not to think about my missing sword or the tome or that life I left at the bottom of the ocean. I tried to do this ‘normal’ thing, to be the kind of man who isn’t obsessed with death – his or someone else’s.

It’s harder to do than I thought.

The bones are everywhere on Teji. I can’t take a step outside the village without stubbing my toe on someone’s bleached face. The reek of death is always present, and so the Owauku light fires to scare away the spirits. They survive off their roaches. The roaches thrive off the island’s tubers. The tubers are the only edible growing things here.

And here, amidst the bones and the death, I thought I would become normal. I thought this was where I could sit back and stare at the sunset and not worry over whether or not I was going to live tomorrow.

Days ago, I was ready to leave this life behind.

Maybe I was wrong.

Things are tense. It must be the water … the air … whichever one paranoia breeds in. Crooked stares meet me wherever I go. People go quiet when I pass. I hear them whisper as I leave.

The Owauku try to hide it, forcing big grins, friendly chatter before they slip away from my sight. The Gonwa aren’t nearly so interested in my comfort. They stare, without shame, until I leave. They speak in their own tongue, in low murmurs, even as I stare at them. And now, they’ve started following me.

Or one has, anyway. Hongwe, they call him, the spokesman for the Gonwa. I don’t know if he’s been doing it for a while and I just caught on or what. But when I walk through the forest, down the beach, he follows me. He only leaves if I try to talk to him. And even then, he does so without excuse or apology.

Granted, if he were going to kill me, he probably wouldn’t bother with either. But then, if he were going to kill me, he’s been taking his time.

Teji is one of the few places I’ve been able to sleep soundly, without worry for the fact that my organs are almost entirely on display for stabbing. And I happen to know from the many, many times Bagagame has told me Hongwe’s watched me sleep that the only thing standing between my kidneys and a knife is a thin strip of leather and a wall of reeds.

So far, he’s done nothing. And as strange as it sounds, I’m not really that worried about a walking lizard that brazenly stalks me and possibly watches me sleep. One wouldn’t think I’d have bigger concerns than that, but it would seem poor form to start questioning it now.

My companions …

I don’t think I’ve ever truly trusted them. Really, I’ve just been able to predict them up to this point. Their feelings are easy to see; their emotions are always apparent. And while I’m not a man who considers himself in touch with – or interested in – such things, I can tell that all of them are holding back something.

Dreadaeleon skulks around the edges of my periphery, almost as bad as Hongwe. I say ‘almost’ only because he spooks and flees the moment he even gets a whiff of me. I may have been harsh with him in the forest, but he’s never … well, rarely been this jittery before.

Denaos tells me, in passing, that Dread is going through some changes. That’s about all he’ll ever tell me. It’s interesting: of all the sins I’ve tallied against Denaos, drunkenness was not one until now. If I don’t speak to him before breakfast, I’ll never understand him before the slurring, assuming he doesn’t go spilling his innards in the bushes. Each time I try to talk to him, he’s got an alcohol-fuelled excuse that I cannot argue against. It almost seems like he’s planning each drunken snore, each incomprehensible rant. Or maybe he just likes his list of sins well rounded.

In such cases as this, Asper can usually provide insight, but she’s been just as silent. And when I say silent, I mean exactly that. Dreadaeleon flees, Denaos drinks, Asper doesn’t even look at me. I might get the occasional nod or rehearsed advice she’s said to a hundred different grieving widows, but she won’t look me in the eyes. I pressed her once; she screamed.

‘ Ask your stupid little shict if you’re so Gods-damned concerned about everything! Pointy-eared little beast knows everything, anyway!’

‘ Humans, eh?’ was the extent of Kataria’s explanation when I did consult said beast. Of all of them, Kataria is the one who doesn’t flee, who will look me in the eyes. I should be happy with this. But she’s the most tense of all, even when she smiles. Especially when she smiles.

She seems at ease, but her ears are always high on her head. She’s always alert, always listening to me just a bit too closely, waiting for me to say … something.

She doesn’t stare anymore.

I never thought I would be worried by that.

I never considered them honest, but I did consider them open. Some more than others. Sometimes I wonder if Gariath, and his constant threats, kept all our tension directed toward him. These bipedal lizards just don’t have the same appeal that he has.

Sorry. Had.

If he’s alive, he’s not coming back. He’s wanted to be rid of us for ages, so he said. Of course, he didn’t seem to want to live very badly to begin with, so perhaps he’s found a nice cliff to leap from. Either way, I hope he’s happy.

I want them all to be happy. I do. I want them to be able to live without war. I want us to part ways and be able to forget that our best memories together were born in bloodshed.

And maybe it’s up to me to help them with that. I am the leader, after all. I should be there for them, help them with this, no matter how drunk, skittish, silent or paranoid.

It won’t be easy. For any of us, least of all me. I hear the voice. Not always, not often, but I know it’s there. I’m likely the one man who shouldn’t be looking into someone else’s life.

But I can do this.

I can do this for all of us.

Tonight is Togu’s celebration, a ‘kampo’, he calls it. It’s something of a joint feast to herald the end of summer and remember the day humans came to their island with salvation from starvation. To hear the other Owauku speak of it, it’s an excuse to drink fermented bug guts and rut.

Sounds like fun.

As good a time as any to gather everyone together, to tell them all that I’ve been thinking, to tell them what we can do, that we can live without war. From there? I suppose I’ll find out.

Hope is not going to come easy.

But I can do this.