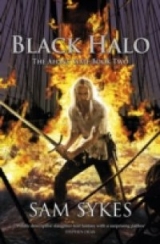

Текст книги "Black Halo"

Автор книги: Sam Sykes

Соавторы: Sam Sykes

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 41 страниц)

Sixteen

THE SIN OF MEMORY

He found he could not remember his name.

Other memories returned to him, vivid as the city that loomed in the distance.

Port Yonder. He remembered its name, at least.

He had lived there once. He’d had a house on the land, back when dry earth did not burn his feet. It had been made of stone that had seemed strong at the time and bore the weight of a family once. He had known the witless, bovine satisfaction of staring up at a temple and praying to a goddess that priests said would protect him. He recalled living through each night, when such knowledge was all he needed.

He had known what it meant to be human once.

But that was long ago. That was a time before he knew the weight of humanity could not be set on flimsy, shifting land. That was a time before he knew that stone, trees and air all gave way before relentless tides. That was a time before his goddess had found his devotion and offerings not enough and had spitefully taken his family to compensate. His name, too, was from that time.

Before he had become the Mouth of Ulbecetonth.

‘Do you desire to know your name, then?’

The Prophet’s twin voices lilted up from the deep. He looked over the edge of the tiny rock he squatted upon, saw the black shadow of a tremendous fish circling his outcropping. He remembered when he had first seen that shadow and the golden eyes that had peered up at him. There had been six of them, then; now there were only four, two of them put out forever by heretical steel.

‘I desire nothing,’ he answered the water, ‘save that the Mother is liberated.’

The realMother, he reminded himself, not the Sea Mother.

The Sea Mother was a benevolent and kindly concept, one that took pity upon the land-bound folk and blessed them with the bounty of the deep. The Sea Mother was a concept that rewarded thoughtless prayer, asked for nothing more than humble sacrifice and protected families in return.

The Sea Mother was a lie.

Mother Deep was mercy.

‘Liberation is a just cause, indeed,’ the Prophet replied. ‘And it is because of that cause that we ask you to return to the prison of earth and wind once more. The Father must be freed for the Mother to rise.’

He found a slight smirk creeping upon his face at the naming of the city a prison. Truly, that was what it was, he knew – nothing more than thick walls constructed by fear, doors made of ignorance and the key thrown away by unquestioning faith.

That smile soured the instant he remembered that they were sending him back there, to feel cruel stone beneath his unwebbed feet and languish in the embrace of air. His brow furrowed and he could feel the hairs growing back even as he did, tiny black reminders that the Prophet commanded and the Mouth sacrificed.

And for what?

As if summoned by his thoughts, he heard the sound of flapping wings. He looked up and saw the Heralds descending from the unworthy sky, their pure white feathers stretched out as they glided to the reefs jutting from the surface. Upon talons that had once been meagre webs, clutching with hands that had once been pitiful gull wings, the creatures landed silently upon the risen coral.

He remembered what they had been before: squat little creatures, wide-eyed crone heads upon gull bodies, incapable of even the slightest independent thought. The faces that stared at him now, still withered, were set upside down upon their crane-like necks above sagging, vein-mapped teats. Their bulging blue eyes now regarded him with a keen intellect that had not been present before. The teeth set in mouths that should have been their foreheads were long yellow spikes that clicked as they chattered relentlessly.

He had once looked upon them as evidence of Mother Deep’s power, the ability to effect change where other gods were deaf and powerless. Now, he saw them only as items of envy, proof that even the least of Her congregation evolved where he stood, painfully and profoundly human.

‘Do we sense uncertainty in you?’ the Prophet asked, stacking accusation upon scorn.

‘Uncertainty?’ the Heralds echoed in crude mimic of the Prophet. ‘Doubt? Inability? Weakness?’ They leaned their upside-down heads thoughtfully closer. ‘Faithlessness?’

‘My protests are unworthy,’ the Mouth replied. ‘All that matters is that the Father is freed. I have no other desire.’

‘Lies,’ the Heralds retorted with decisiveness.

‘Irrelevant,’ the Mouth replied. ‘Service is all that is required. Motive is unimportant.’

‘Ignorance,’ they crowed in shrill chorus.

‘What great sin is desire, then? What is the weight that is levied upon my shoulders for my want of vengeance? Mother Deep’s enemies are my enemies. Her purpose is my purpose.’

‘Blasphemy,’ the voices hissed from below.

The Prophet’s twin tones contained a wailing keen, the subtlest discordant harmony that shook his body painfully and caused him to wince. How he longed to abandon his ears with what remained of his memories. How he longed to embrace the Prophet’s shrieking sermon with the same lustful joy as the others.

Mother Deep demanded sacrifice, too, however.

‘You suffer doubts, then,’ the Prophet murmured, four golden eyes regarding him curiously.

‘Intolerable,’ the Heralds muttered. ‘Inexcusable. Unthinkable.’

‘I had not expected to be asked to return here,’ he replied, staring out over the walls. ‘I left this place, and all its callous hatreds, on land where it belonged.’ He hugged his legs to his chest. ‘I found reprieve in the Deep.’

But not salvation, he added mentally. He had been granted gifts: the embrace of the water, freedom from the greedy liquid hands that sought to steal air and quench it, and the loyalty of Her children. But the true mercies of Mother Deep had been withheld from him, for the moment.

And yet, he lamented, that moment had lasted for years that only made his awareness of the passage of time more profound.

He gazed down into the water, below the swimming shadow of the Prophet, and saw the faithful congregate in pale flashes as they boiled up from below. The fading sunlight shifted on the water hesitantly, wary to expose the creatures bobbing below it. And, as the golden light speared through the waves, a great forest of hairless flesh, swaying on the waves, met his eyes as hundreds of glossy stares incapable of reflecting the light looked up.

They floated so effortlessly, bodies lent buoyancy with the absence of memory. They were oblivious, ignorant to what their lives might have been when their feet lacked webs and could abide the feel of land beneath them. They were blind to the meaning of the rising and setting of the sun. They were deaf to the world, save the wailing chorus of the Prophet’s twin mouths, which he could not abide, and the distant call of Mother Deep, which he could not yet hear.

And, he thought resentfully, they sacrificed nothing.

They gave themselves fully, ate of the fruit of the Shepherd’s births, and were freed from their memories and the embrace of greedy, lying gods. He had abstained, at the Prophet’s request. He had become the Mouth and was denied their serenity, their bliss.

Their freedom …

And he … hehad given everything. He had abstained from the embrace of Mother Deep’s children, and for what? That he could be tormented still with his own ignorance? Taunted with the years he had wasted on a goddess that spared not his family? Agonised with the visions of their faces, the memories of their laughter?

And now, now they asked him to return to the land, to bear the stain of solid ground and recall the memories they had promised to take away from him. What he saw when he looked up across the channel at the docks he had walked off of, following three voices in the night, was a return to sinful memory and the company of ignorant airbreathers.

Not the salvation he had been promised.

‘And for what?’ he muttered. ‘This brings us no closer to the book.’

‘An ocean is a vast and tremulous thing,’ the Prophet replied coolly. ‘Its sheer magnitude makes it incomprehensible to view with mortal eyes. Where a gale blowing from the west may seem separate from a wave roaring in the east, they meet in the middle as a raging maelstrom.’ The shadow of the fish’s body paused thoughtfully. ‘And even then, it cannot be fully fathomed unless viewed from below.’

He could see flashes of white in the darkness as two broad mouths split open in wide, fanged smiles.

‘She sees where we cannot,’ the Heralds burbled in agreement. ‘Thinks in ways we cannot comprehend. The maelstrom whirls, swirls chaotically, inexplicably.’

‘But it is nonetheless felt,’ the Prophet added quietly. ‘The Mouth should not concern itself with the book. Mother Deep has seen to its return.’

He might have asked how. How could any creature, even one that made such promises and delivered such freedom as Mother Deep, affect anything beyond the bonds of her prison? How could she promise the salvation so freely, knowing that hers was a hand still wrapped in chains?

He might have asked, but recalled too keenly the wisdom of the Shepherds, delivered from their gaping jaws to the unworthy grasped in their oozing claws.

Memory was a burden. Knowledge was a sin.

‘A key, after all,’ the Prophet continued, ‘is but one part of a door. There must be hinges upon it to swing and hands to turn the knob.’ Golden gazes drifted toward the distant city. ‘If those hands should be freed from unjust bondage, so much the better.’

‘Better,’ the Heralds echoed. ‘The sons need a father. The faithful need a leader.’

Beneath the waves, something stirred in agreement.

Below, he saw the thousand glossy stares of the faithful turn in unison toward the city, as though something had called to them in a great, echoing call. Darkness stirred beneath them, where the light did not dare to touch, and he saw the great white stares of the Shepherds rise to add their attention.

It angered him that he could not hear what they heard, see what they saw. Before them loomed a prison in their eyes, an unjust and foul dungeon of stone and wind wherein lay the salvation he could not claim. All he could see was the lies and hate that had driven him to the deep in the first place.

What they heard, he could only make out faintly. Even as far away as he was, through the roiling waves and over the murmur of wind, he could hear it. Slowly, steadily, with a patience that had outlasted mountains and earth, it droned like small hands upon a large door.

A single heart, beating.

He supposed, he thought dejectedly, he should be thankful that he was blessed enough to hear even that. His ears burned enviously with thoughts of what the congregation might hear, what bliss it might bring minds wiped clean of memories and lies.

‘Impatience does not become the position She chose you for,’ the Prophet said coldly, as though sensing his thoughts.

‘At times, the reason for my choosing becomes obscured,’ he replied just as brusquely.

‘Is devotion no longer reason enough?’ the Prophet asked.

‘Recall the maelstrom,’ the Heralds agreed. ‘It is-’

‘I cannotsubsist on metaphors,’ the Mouth snarled suddenly, his patience lost in a sudden surge of grief. ‘Words do nothingto diminish the memories, to make me forget that Iam denied the gifts of Mother Deep that are promised to the less faithful!’

‘In time!’ the Heralds squawked in protest. ‘In time, there will be-’

‘Will be what?’ His frustration inspired words that he knew he should not speak, gave force to will that he knew was sinful. ‘All your promises, all your great plans have availed us nothing! The tome is lost, the longfaces drive back the faithful time and again, even desecrating the Shepherds with their vile poisons! And now, while they sniff out the book like landborne hounds, yousit here and point me toward the very city I turned to you to free myself of?’

He drew in a sharp breath whose saltless taste was yet not foul on his lips. He narrowed eyes that were not glossed over, clenched fists that were not webbed, as weak, sinful emotion came flooding into him.

‘Occasionally, Prophet,’ the man hissed, ‘gales and walls of water are nothing more than mere winds and waves, each without substance.’

Satisfaction was something he knew he should not feel. It was, like all sensations outside of unrelenting devotion, a sin, and he made himself stern with the knowledge that it would be punished. He imagined himself being torn to shreds by the Prophet’s shriek, the same wailing doom that had wrought ruin upon the faithless and blasphemers that stood in the way of the faithful.

Perhaps, he thought, that was as close to hearing the harmony in its words as he would ever come.

The Prophet circled his outcropping silently. The Heralds’ relentless crowing had fallen silent; they tilted their heads right side up in curiosity. The golden eyes were dark below. The congregation was still, suspended motionless in the water. Even the white stares of the Shepherds had vanished, as though afraid of what wrath awaited their former preacher, Ulbecetonth’s Mouth.

But after several painful breaths, all that emerged from below was a pair of melodic whispers.

‘Our pity is well given to you,’ the Prophet said softly. ‘Perhaps we have become too much like the Gods that ignore your cries. But we are not deaf …’ The voices snaked up like vocal tendrils, caressing him with slender, shimmering sound. ‘Your agonies are heard. Your faith shall be rewarded.

‘You wish your sinful memories to be absolved, the tragedy of your life to be eased inside your mind,’ the Prophet continued. ‘It shall be done. Yours will be ears closer to the Mother’s song than any of the faithful. All that is asked of you is that you grant Her one more favour.’

He drew in another deep breath, felt his heart pound with anticipation.

‘Free the Father,’ one Herald whispered, its voice carried on the wind.

‘End the injustice of his imprisonment,’ another hissed.

‘Lead the faithful to salvation,’ more crowed.

‘Free him,’ they burbled. ‘Free him … free him … free him …’

‘Let him crush the earth beneath his feet again.’ The Prophet’s voices silenced the chorus. Gold eyes turned upward again, burning with purpose. ‘Liberate Daga-Mer.’

As the Prophet’s voices echoed, fading with each moment, another sound grew stronger. As if in the moment before a great drawing of breath, it echoed from the deep and carried to his ears.

A heartbeat.

The Heralds scattered at the sound, taking wing on shrieks of ecstasy as they twirled and writhed in feathery columns stretching toward the sun-stolen sky.

Another beat, louder.

The faithful stared up, their mouths splitting open in broad, toothy grins. Their eyes quivered in the rising starlight, as though they might add their own joyful salt to the sea.

Another.

The Shepherds dropped their jaws open, exposing sharp teeth as they howled some ancient hymn that went unheard, rising to the surface on bubbles that popped soundlessly.

Another beat, loud and clear as if it were that of the Mouth’s.

And he felt himself smile to hear it.

The water called to him and he obeyed, sliding in. It embraced him like a family that would never leave him, never deny him. He swam silently upon its tide towards the distant prison of earth and air. He swam, sliding through the waves as a world of dark flesh, dark eyes and glorious faith moved beneath him.

He swam, dipping his head below the surf.

And through it, he heard the Father calling.

ACT TWO

Island of Hope and Death

Seventeen

BETTER OFF IGNORANT

The Aeons’ Gate

Island of Teji

Summer, pleasantly so

One of the more sobering realisations I have stumbled across since I first picked up a sword is that society, at least as we know it, does not exist.

Of course, I’m actually a little disappointed to put it down on paper. After all, I had rather enjoyed the ideas behind civilisation: linking together against common enemies, joining like-minded trades and arms for mutual prosperity, the coalition of many single gods for the benefit of all and, of course, the keen urge to keep one’s neighbour close so that, when he finally did knife one in the kidneys and steal one’s sheep, at least one couldn’t claim they didn’t see it coming.

Regardless, my most horrific discovery has been that society is nothing more than a series of carefully calculated choices based solely around economics. That’s it. No like-minded philosophies, no common gods, not even healthy distrust made it possible.

Just gold and greed.

Any other thoughts I’ve had about this were quickly banished once I arrived on Teji and was subjected to the curious company of the Owauku. As far as I’ve been able to tell from as far as I’ve been able to understand their language, Tejiwas a thriving trading post, as Argaol informed me … once, anyway.

Humansused to live here. That much is clear by what has happened to the locals. I’d seen some of the more remote societies on the outskirts of Toha when we first began looking for the Aeons’ Gate, as Miron originally hired us to do. They tended to have both a keen distrust for me and a keen intent on putting something sharp in my guts.

Or an arrow in my shoulder, as the case may be.

The tall, tattooed lizardmen … they’re called ‘Shen’, the Owauku tell me: raiders, scavengers, generally as uncivilised as one would expect loincloth-clad reptiles to be. Of them, I know not much else, save that the Owauku have driven them off. They’re gone.

So they tell me.

The Owauku … are friendlier than most. Almost too much. They offer us freely their meat and drink, at least what passes for meat and drink, but with the subtle gleam in their eyes that suggests something would be appreciated in return. That gleam, anyway, is what I deduce from the times I can stand looking in those giant melons they call eyes. They do this … thing … where they look at me with one eye, then look at something else with the other, and they keep moving in different directions and …

Never mind. It’s too disgusting to recount. It does make one yearn for the company of the Gonwa, though. Those taller, bearded things that I saw in the forest apparently share the village with the Owauku. I can’t imagine why; the Gonwa are tall and stoic where the Owauku are short and spastic. The Gonwa are reserved and distrustful where the Owauku are almost offensively open. The Gonwa only look at me when they think I’m not looking at them, and sometimes with murder in their eyes, while the Owauku look at me …

No. No. Disgusting.

The point is that the Owauku have and love and the Gonwa lack and loathe everything one might find in a city: gambling; smoke, in both cigar and hookah form; alcohol, from their own making; and various other sundries and goods remnant from when humans still traded with them. The little ones adore the idea of trade, and constantly ask us if we have anything to put forth in that regard.

What they think we have, I really can’t even begin to wonder. They’ve already taken our pants …

Anyway, as I was saying, the idea of everything important being driven by economics does not apply solely to society. In the age we live in, it’s become a healthy substitute for instinct. If something costs more to get than it’s worth, then it’s not worth the effort. It’s that easy.

And, with that in mind, I’ve decided to follow my instincts …

And give up.

I’m through. I’m through with everything. I don’t want to have anything to do with Miron, with books, with bounties or monsters or netherlings or demons ever again. Especially nothing to do with books. I nearly lost all my companions, and did lose at least one, searching for the stupid thing.

Once, long ago, that thought wouldn’t have seemed so bad. But … that was before. Before I stopped fighting, before I put the sword down and had a chance to breathe. It wasn’t by choice that I stumbled across this realisation. On Teji, there’s nothing to fight, nothing to kill, nothing to worry about killing me.

And … I find that I kind of like it.

Without anything’s entrails to spill upon it, I find myself doing a lot of walking on the ground instead. I spend most of my days walking down the beaches with Kataria, listening to her tell me about the various plants, shells and driftwood we find. At least half of the stuff she spews, I’m certain she’s making up, but every time I feel like accusing her, she smiles and … looks at me.

Notlook looks at me, but … looks at me, like I’m something she wants to look at. She stares at me, not in the way that suggests she’s looking for something beneath my skin, but like my skin is fine as is. She stares at me and I don’t mind. There’s nothing screaming in my head.

I’m … not hearing the voices anymore so much.

I’m even starting to remember my old life, before this all happened. I can remember my family. Not their names, but their faces, the colour of my grandfather’s beard, the feel of the calluses on my father’s hands, the smell of the tea my mother brewed in the morning. I can remember cows I’ve milked, dogs I’ve fed, barns I’ve swept …

All while I’m around her.

It’s not all great, to be perfectly honest. I still dream, and when I do, I dream of flames, of big blue eyes without pupils. And while I’m at ease with the Owauku, their taller, bearded friends, the Gonwa, eye me with distaste. Perhaps they knew, at one point, I planned to kill them? I don’t see why they would take offence at that, really. I didn’t know them at the time; it was going to be a perfectly honest killing.

And … I’m still hearing the voices.

That’s another thing. I did just write ‘voices’, with an ‘s’. There’s another one, I think … a fainter one than the first one, not so loud, not so demanding. The first one was like a fist: jabbing, pounding at the door to let it in. This one … is subtler, like a wiggle of the knob, a hand pulling at the sheet around me, someone moving a cup of tea from where I set it down.

And sometimes, it’s not so subtle. It tries to break the door down, tears the sheet off, slips and breaks the cup. It gets so loud … so ANGRY …

But let’s not think about that. There’s more important things to worry about.

For example, Sebast is now almost a week overdue. The ship that Argaol promised to send to pick us up has never been seen, even when Kat and I wait on the beach for any sign on the horizon. The Owauku assure me that if any did arrive, they would tell me. Frankly, I believe them, since any boat that came would be instantly harried by them as they sought to trade with it.

I should be more worried about this than I am. But I’ve since decided that Argaol wasn’t as good as his word. It’s really not that big a surprise; he managed to get six bloodthirsty lunatics off his ship. Why would he send anyone to go get them back?

Still, I’m not too worried. Even if it’s fallen into disuse, this is still a trading post. It’s still close to the shipping lanes. There’s no reason to expect that a shipwon’t eventually come by. If all that means is a few weeks stuck in a loincloth walking down the beach alongside Kat, who I must say looks pretty smashing in her own, then I’m fine with that. Naturally, I’m a little disappointed that there are no more humans on the island.

Strange, though, I don’t recall if Togu ever told me what happened to them.

Not that I go out of my way to spend time with Togu, actually. Amongst the Owauku, or even amongst all the horrible things I’ve seen, he definitely ranks as one of the worst. He is living proof that the Gods exist and that their sense of humour appeals only to themselves. It’s as though they made some dwarfish, scaly creature with giant gourds for eyes and a horrifyingly strange accent and decided he just wasn’t irritating enough without having the insufferable speech prowess of a six-headed politician crossbred with a forty-handed merchant.

I’m content to mostly spend time with my companions, even if the reverse isn’t true.

Asper has nothing but harsh words and ire for me, though I gather she’s short with everyone these days. Why, I cannot say. I know something … occurred when she was tending to my wounds, something that is largely accredited to the stress of the situation and her lack of clothes. Denaos tells me something similar occurred shortly after she woke up and spoke to Dreadaeleon. He didn’t have any time to check on her, of course, since shortly after, he made the acquaintance of the Owauku and became wise to their insatiable voracity for human pants.

Either way, his attentions are solely on her, in the same way a voyeur’s attentions are solely on a lady’s unguarded window. Dreadaeleon isn’t much better. His conversation is curt and brief and, every time, he always scampers behind a hut or a bush to avoid me. If I wasn’t so trusting, and if I didn’t care so little, I’d say he was hiding something. And every day I thank Khetashe that pubescent wizards are as loath to share their problems as I am to hear them.

We’ve kept eyes open for signs of Gariath, albeit not very widely. Perhaps it’s just the peace that Teji has infected me with, or perhaps it’s the fact that he’s a deranged, flesh-eating lunatic, but I can’t say there’s much of a reason to look very hard.

In short, I have to say that Teji might be the best thing that happened to me. Despite the disappearance of my sword, the tome and all my clothes, I’m … almost happy.

A ship will come, eventually. We’ll get new pants. We’ll get new boots. We’ll clean the sand from our buttocks, wash our faces in fresh water, read books with real words and never have need to pick up a sword again.

Hope … doesn’t seem such a bad thing.