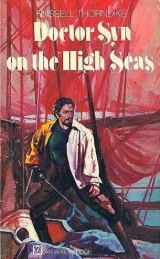

Текст книги "Doctor Syn on the High Seas"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Chapter 7

The Friend of the Family

At the coroner’s inquest, held in the card-room at Iffley, it was

apparent to the conspirators that no hint of suspicion that a trick had

been played upon them had entered the minds of the jury. Indeed, the

coroner himself opened the proceedings by stating that the case was a

straightforward one, and need not detain them long. In the absence of

her mother, who was too ill to attend, Imogene recounted to the court

the details of their cruel abduction from White Friars. She stated that

while her mother was locked in one room, the deceased had attempted to

love her forcibly in the very room in which the court was sitting. She

told them of the letter which the Squire had sent to Doctor Syn, and

which had been the means leading to their rescue. The unexpected

arrival of Captain Nicholas Tappitt, who had known them in Spain, backed

by the presence of Doctor Syn and his friend Mr. Cobtree, had insured

their safety, but not before the Squire had heaped such insults upon her

mother and herself as Doctor Syn, as a man of honour and her betrothed

lover, could not tolerate. The result was the meeting next morning in

Magdalen Fields.

The three young men were then called, and told the same story. They

had agreed that no mention should be made of Sommers or of the s ecret

stairway, but Doctor Syn found himself continually staring at the panel,

half expecting the avenging farmer to appear and tell the truth. But

having accomplished his work of vengeance, Sommers was wise enough to

remain on his side of the river.

After the details of the duel had been given by the seconds, the

pistols and fatal bullet were exhibited, and the two gypsies took their

stands as witnesses. The coroner said that there was no doubt in his

mind that the duel had been carried out with the strictest regularity

between gentlemen in an affair of honour, the jury agreeing that

everything was perfectly regular. As a matter of course they were asked

to view the body in the shuttered bedroom of the deceased, where the

surgeon bewildered their simple minds with the longest medical words at

his disposal, and the most of them were thankful that the stiffened dead

man’s hand was completely covering the actual wound.

A verdict of “Death in an Affair of Honour” was returned, and the

coroner wound up proceedings with a tribute to the young parson’s

courage, and to Captain Tappitt’s impartiality. The Captain’s behavior

had been gentlemanly throughout, and he hoped he would live long to

enjoy his sudden inheritance.

The results of the inquest brought another flood of congratulations

to Doctor Syn from all classes of the town and countryside, to which Syn

replied wistfully that he had yet to face the Bishop of The Diocese on a

charge of violating his cloth.

But the Bishop, neither wishing to fly in the face of public opinion

nor to give the appearance that he was swayed by it, pretended to be

ill, and begged the Chancellor to take over full responsibility and

advise him of the results. The Chancellor pointed out to his Lordship

that although nominally Head of the University, and conveniently

resident in Oxford, the duty of presiding over such a court must fall

upon the Vice-Chancellor, who was responsible for keeping the peace in

the colleges. Fortunately for Doctor Syn, this important official was

also his good friend, so that when two days later the young Doctor took

his stand before an assembly of clergy convened in the Sheldonian

Theater, he felt confident that the court would take no drastic steps

against him.

– 51 -

The Hall was packed, not only with students, but with all the fashion

of the neighbourhood, and although the Vice-Chancellor thundered against

the evil practice of dueling, warning the students that should any of

them take part in such an affair he would be sent down in disgra ce, yet

he owned that in this particular case he felt obliged to deal mercifully

with such a brave young man.

Thus was Doctor Syn acquitted, and that very night a supper was given

in his honour by the students. Both Tony and Nicholas went with him,

and since it was held in an upper room of the old Mitre Inn, which

Doctor Syn was in no mind to check, the jolly students drank themselves

beneath the table. Neither Tony nor Nicholas could out drink Doctor

Syn, and they afterwards confessed that although he drank as much as

any, he was the only one who remained sober. Nicholas swore that such a

grand capacity was wasted in a parson. But Doctor Syn was yet to know

how useful it was to be able to consume more bottles than the next man

and yet come out clear-headed.

In the days that followed, Doctor Syn discovered that an admiration

which he had never quite resisted for Nicholas had developed into a fast

friendship. Possessed now of his uncle’s wealth, the young man began to

enjoy life with zest, and insist ed that his friends should do the same

and share his fortune with him. Nothing could daunt his kindness and

concern, and he would wave aside their continual gratitude with “I am a

friend of the family, I hope?” Imogene especially delighted in his

company, and Doctor Syn was glad of this, since, owing to the mother’s

illness, Imogene was kept somewhat a prisoner in White Friars. Nicholas

was a welcome relief to the girl from the monotony of nursing. It was

delightful to talk of her beloved Spain to someone who knew it well and

could converse in excellent Spanish. He was also a proficient performer

on the guitar, and could sing her favorite love-songs.

Seeing that Imogene loved to speak her native tongue and her it

spoken, Doctor Syn resolved to learn, and in this he was helped as much

by Nicholas as by Imogene herself. On one occasion when Nicholas had

praised him for an improved accent and an ever-growing vocabulary, the

Doctor cautioned him in jest with:

“You must take care, you know, for I shall so on be understanding all

you say to one another.” At which Nicholas laughed and said:

“I have no guilty secret, since I have always told you to your face

how much I am in love with Imogene, and one of the things that makes me

love her more is that she is in love with one for whom I have the

deepest affection. Aye, and for Tony too. He also is a man after my

own heart.”

This affection he took every means to prove, and at this time the

lovers owed him much, for when the question of their immediate marriage

had been breached, the Senora had proved querulous, complaining that her

daughter was regarding her as a hampering invalid. This unjust

accusation hurt the lovers deeply, but Nicholas, laying the blame upon

the mother’s nerves rather than any settled wish, at once began to set

the matter right, and his business in their affairs had a happy and

speedy result; for at this first argument upon the matter, he returned

and told his friends that he had persuaded her to admit that she was

fond of Christopher, though him a suitable husband, and that her chief

desire was to get well quickly in order that she could take her rightful

part in the wedding festivities.

This news delighted Tony as much as the lovers, for it had been his

idea that a double wedding would be the grandest occasion, since his

parents treated Doctor Syn as another son. But it was Nicholas who made

all the arrangements, and through his energy both sets of banns were

cried upon the

– 52 -

very next Sunday at Christ Church. The invit ations were sent out

immediately, and at his own request Nicholas was appointed Best Man in

attendance under Doctor Syn.

Some days before the actual ceremony, the Pemburys and the Cobtrees

set out with a vast retinue of servants from distant Romney Mars h. All

through the preparations Doctor Syn had nothing but admiration for

Nicholas, who seemed capable of running everybody’s business and his own

as well. It was he who even arranged the two honeymoons.

“I suggest,” he said, “that Tony and his bride accept my offer of the

Iffley Farm in the Cotswolds. The house is comfortable, though remote,

and that scenery romantic. They will be well cared for by my tenants.

Then, since Sir Charles and Lady Cobtree are to be in London for their

annual visit, what better than that you, Christopher, should take

Imogene to Dymchurch? You have been offered the Court-House during the

family’s absence, and Imogene will have opportunity to know the village

which will be her future home, when you decide to leave Oxford and

become Vicar of the Marsh.”

He also undertook the convey the Senora back to Spain aboard his

trading-ship, for the Senora had decided to return to her own people

after the wedding.

Although Nicholas proved himself a “friend of the family” indeed.

Needless to dwell on the gay happiness of those festivities. Thanks

to Nicholas, all went with a swing, and when at last the radiant couples

drove off in their respective carriages, the many guests declared that

never had young married people started out upon the voyages of mutual

responsibilities under more favourable auspices. The one tinge of

sadness was Imogene’s parting from her mother, but it was understood

that as soon as times permitted, she and her husband would take passage

with Nicholas and visit her.

The days that followed were the happiest of the Doctor’s life. He

had been granted a month’s vacation from his College duties. He was

then to return to Oxford work until his induction to the Dymchurch

living. Sir Charles had arranged that t his should be as soon as

possible, since the old Vicar was only too anxious to retire to private

life. This kindly old man allowed the young couple free access to their

future home, and Doctor Syn was thus enabled to plan the various

alterations which Imogene suggested for the house. On the assurance from

his uncle, Old Solomon Syn, the Lydd attorney, that there was no great

need to study economy, the young parson spent freely, buying whatever

furniture and house trimmings pleased his bride. These two rooms were

to be thrown into one, to afford the Doctor a more spacious study. This

he allowed on her suggestion, on condition that she allowed the

breakfast-room to be discarded to give more space to her drawing -room.

Each proposal gave birth to a dozen more, until the bewildered old Vicar

mildly remarked that they might as well pull the old house down and

start to build a fresh.

“Oh no!” cried Imogene. “I love these whitewashed walls. They remind

me of the white walls of Spain. And if we built another wing to match

that of the new kitchens, the old Vicarage would be like an ancient gem

in a new setting.” And so another wing was planned.

“But what use we shall we put the extra rooms to, I cannot imagine.”

“I suggest,” said the old man —”and hope so too—that ere long you

may need nurseries.”

“Of course,” replied the delighted Imogene, without the vestige of a

blush. “We must have house room for the children, Christopher.”

Eyeing the back of the house, where the garden ran down in a gentle

slope to meet a broad dyke, Imogene clapped her hands as a new idea was

born.

– 53 -

“Although I must not disturb you when you work in your library, we

would feel nearer to each other if we joined our rooms upon the outside.

We could keep our windows wide open and feel we were in the same room.”

“Whatever do you mean?” laughed the Doctor.

“Outside our bedroom window,” she explained, “we could build a

balcony. Supported by pillars from the garden which we can pave, we

would have a lovely Span ish alcove outside our sitting-rooms. In the

sun, if it ever shines here, we could sit under it, and when Nicholas

comes to visit us he will be able to sing us his lovely Spanish songs.

Oh, Christopher, I shall always sit there if you will have it built.

You will? You must. To please me?”

All this was duly explained to the builder, an old friend of the Syn

family and a Dymchurch man, who could build anything from a boat to a

castle. His name was Wright, and it was he who first opened Doctor’s

Syn’s eyes to something about his wife which he would never have though

possible.

“I should think well, Reverend Sir,” he advised. “these alterations

will cost money which will be wasted should your lady wife decide to

move. She is no lover of our marsh, I can see.”

This attitude had never occurred to Doctor Syn. Loving the Marsh as

he did in all weathers, he imagined that others would feel the same

appreciation for it. This worried him, and whenever he saw a sad look

come into his bride’s face, he wondered whether it was homesickness for

Spain and mother, or dislike of the place that was to be her home.

When she realized that he was disappointed at her lack of enthusiasm

for the Marsh, she pretended a growing liking for it, but as the time

approached for their return to Oxford she could not disguise her joy.

He did not know whether this was occasioned by the thought leaving the

Marsh, or the prospect of returning to White Friars, where they had

taken rooms. When he asked her outright she gave a different reason.

She wanted to be at Oxford to welcome Nicholas on his return from Spain.

“Of course you do,” cried Syn cheerfully. “And so do I. I miss the

jolly rascal more than I can say.”

Chapter 8

The Elopement

Soon after their return to Oxford they received a letter from

Nicholas stating that urgent business had kept him in Spain, and that he

had been obliged to let his ship set sail without him, but hoped to be

aboard her upon the next home voyage. He asked them to send an answer

containing all their news by the hands of his sailing-master, who was

then discharging cargo in London Docks.

You will be glad to know, my dear Imogene, that I escorted your dear

mother safely to her home, where I have seen her constantly. She is

already comp letely recovered from her shock, and is glad to be once more

in the sunniest of countries. I trust, my dear Doctor, you are becoming

proficient in the Spanish tongue. It will amuse you to know that I am

passing everywhere as Spanish born. This I have done with the Senora’s

connivance, because we found the English are unpopular, owing to the

political state of Europe. Will you therefore be so good as to address

whatever letters you may care to send to Senora Nikola Tappittero, which

is the high-sounding name I have adopted? You would be shocked to hear

how venomously I rave against the British people.

– 54 -

It is the only means by which I can get some honest trading. For you,

my dear Imogene, I have purchased a scented lace mantilla, if indeed an

English parson’s wife be allowed to wear such vanity. Also a guitar of

such sweet tone that it took my immediate fancy. The case, too, is very

cunningly inlaid. For the diversion of our dear Doctor, I have run to

earth a fine old edition of comical Don Quixote.

Although no scholar myself, I have yet appreciation for his wit.

Trusting to find you both in Oxford still on my return, I subscribe

myself

Your Spanish friend of the family,

Nikola Tappittero.

A postscript added:

I hope the ho neymoons were happy both in Dymchurch and the Cotswolds.

I have sent my felicitations to our excellent Tony and his bride.

“Oh, Christopher,” cried Imogene, “promise to stay at Oxford till he

comes. Dymchurch seems so far away.”

“Are you anxious for the mantilla and guitar?” he asked, “or is it

Nicholas you want to see?”

“I want to be warmed with the reflection of the Spanish sun,” she

answered.

The mail brought constant news from Dymchurch. Tony and his bride

had returned, were duly thrilled at the rebuilding of the vicarage,

which work was going forward rapidly, since the old Vicar had moved into

his house at Burmarsh, praising especially the Spanish alcove which they

said was something like a cloister. Doctor Syn noticed that Imogene was

more interested in this than in all the other additions put together.

“Tony says that the builder has let in two double seats in the wall

of it,” she said. “He says it will hold us two in one, and than in the

other. But when Nicholas is with us with his guitar, I except he will

sprawl all over one of them, just like a lazy Spaniard. But we shall

see him first in Oxford. Promise me that, my Christopher?”

“That promise you must get from Nicholas,” he answered. “Duty is

duty, and Sir Charles is anxious for me to take mine up as soon as

possible. My Induction papers will be ready in a week or so, and when I

am commanded, I must go. If the house is not quite ready for you, I

could come back here to fetch you when it is. I would rather you came

with me, though, for we could stay at the Cobtrees’, and your wishes for

the house could be the easier carried out.”

“Let us write and tell Nicholas he must come back on the next homing

voyage.”

And she made her husband sit down there and then pen a letter to

Spain. To this she put a postscript in Spanish:

– 55 -

You will please be obedient, and not fail us. I cannot leave Oxford

without my mantilla and guitar, and my Doctor wants his book. But more

than all we want to see and talk with you, Nikola Tappittero of Spain.

How I have laughed at that! If you see us before we go to Romney Marsh,

you will escape the mists of winter here. Oxford is bad enough. Oh,

what a climate! I wonder sometimes how Englishmen are as lively as they

are. I hope you wil l bring us the latest songs of Spain.

Which postscript somewhat distressed the good Doctor. But he said

nothing. After all, Nicholas was no Spaniard.

Though many of the students who visited them were lively enough,

Imogene found Oxford people conn ected with the University took like and

themselves very seriously. Even Doctor Syn, by reason of being the

youngest Don, has automatically adopted a gravity of manner suitable to

his responsibilities. To Imogene the subjects that he taught were

deathly dull: dead languages and Ecclesiastical Law. To cope with such

grave writings, he seemed to her to have wrapped his soul in too somber

a cloak. The only thing that he approached with a lightness of spirit

was his study of Spanish. Here he was the student and the teacher, and

it annoyed her that he did not attach the same importance to her living

language as he did to his own dead ones. This fault, although she did

not realize it, was largely of her own making, for unconsciously she

talked so much of Nicholas and Spain, that in Doctor Syn there began to

grow a jealousy. Not owning this even to himself, he gave her no

warning that such a thing existed. During Spanish lessons she adopted

his own manner of teaching. She railed against the smallest mistakes,

and pronounced his accent as execrable.

He excused himself by saying: “It is the fault of our cold English

voices, my dear. We cannot speak a foreign tongue to the manner born.

We are perhaps too aloof to be good imitators. In the colder languages

of the North we might become convincing, but French, Italian and your

Spanish need a warmer voicing than we can give, and I think no Britisher

would ever deceive a native.”

Her answer irritated him. “Nonsense!” she cried. “Nicholas speaks

Spanish like a Spaniard.”

“He has lived in Spain,” he argued sharply. “And what do we know of

his parents? He never speaks of them. If he is fully English, I am much

deceived. Think of his complexion. There is surely foreign blood in

such swarthiness.”

“If you compare him to your Tony,” she replied, “he may not look so

English. But why be so ungenerous to your good friend? Is the English

complexion the only perfection?”

She looked so scornful in saying it that he took her in his arms and

whispered: “Yours is the most perfect complexion in the world. We both

agree on that, at least.”

“No doubt it will become more English,” she answered, “when beaten by

those flying mists on Romney Marsh.”

The Southern sun in you will drive our mists away,” he said. “And I

am sorry if I appeared ill-tempered I had no right to disparge Nicholas.

You have much in common, and for that I like him, and like you to like

him. But tell me that you love me?”

“I love you, Christopher.” Then she kissed him and smiled. “And

might even love you better still, if you would only laugh as much as

Nicholas.”

“It suits his gay clothes better than my black cloth,” he said. “But

I’ll be livelier when away from all these pompous Colleges. The sooner

we leave, the sooner will you se e the change in me.”

– 56 -

“But you are not leaving till Nicholas comes,” she said teasingly.

“You have given me your word on that.”

“Not that I recollect,” he laughed. “But since I can refuse you

nothing, there, I promise you. I’ll make the rogue my curate, if you

like. You could keep him well in order as his Vicar’s wife.”

And at the thought they both laughed and were happy.

To atone for this argument, Doctor Syn constantly talked of Nicholas,

expressing hopes for his speedy return, and for the same reason of

contrition, Imogene appeared to have lost interest in him.

It had been arranged meantime that Doctor Syn should be inducted into

his Living on the day week following the closing of the Oxford Term. As

the time approached with no news from Spain, the Doctor became anxious,

for he had not calculated that either business or contrary winds could

delay Nicholas so long, and he had given his promise to Imogene not to

leave, and yet he knew the inconvenience he would cause should he not be

in Dymchurch for the Induction. He therefore told Imogene of his

anxiety, and found, much to his relief, that she attached small

importance to it.

“But you must go, of course, my dear,” she said. “We will both go.

The Vicarage is finished. There is nothing to delay us. . Nicholas

must blame himself if he is so tardy. If he wishes to see us at

all, he must take the long ridge to Kent. We have at least

built a Spanish porch to accommodate him and his guitar.”

“You mean that we will go together?” asked Syn, delighted.

“Am I married to you or to Nicholas?” she asked.

“To me, and thank God for it,” he exclaimed.

“Then there is no more to be said, but I like you all the

more for offering to keep your promise.”

Battered by heavy seas and hampered by headwinds in the

Channel, Nicholas returned to Oxford but two days before Doctor Syn and

Imogene were due to set out by coach. Owing to his wife’s change of

attitude towards Nicholas, Doctor Syn generously welcomed the voyager

with more enthusiasm.

“There is no need to inquire after your happiness, Doctor,” said

Nicholas, “for I never saw you so gay in manner. But what has befallen

Imogene? She appears mighty solemn. I trust he is not taking her duties

as a parson’s wife too seriously?”

“She is delighted with your gifts, Nicholas,” he answered. “Believe

me, she had been most anxious to see you before we had to leave.”

Seeing that he had now no cause for jealousy, Doctor Syn reproved his

wife in private for the cold attitude she was showing toward their

friend.

“I am in a mood to be irritated by him,” she explained. “He is so

vastly pleased with himself. Also I am not feeling well. I have the

heaviest head imaginable, my nerves are all jangled, and with your

permission there is nothing I should like more than to spend the day in

bed.”

Having handed her over to the care of the motherly landlady, who was

very fond of her, Doctor Syn was very glad to be able to give Nicholas a

solid reason for Imogene’s indifference, for he did not like to see such

a jolly rogue so dismally cast down. One the advice of the landlady, a

physician was summoned, who reported that although there was no cause

for alarm, the patient was nevertheless suffering from a nervous

disorder and there could be no question of allowing her to undertake the

strain of a long coach journey to Kent. On the contrary, he insisted

that she must be confined to the house for at least a week.

– 57 -

Doctor Syn, in his anxiety, first thought of canceling the ceremony of

his induction till such time as his wife could recover. In this,

however, he was overruled not only by Imogene herself, but also by the

landlady, who avowed that the young husband would be better out of the

way so that she could give all her care to t he patient’s recovery.

“There are times,” she said, “when a young wife is best left alone in

a mother’s care. I have had daughters myself, and I know. You may

safely leave her to me and the physician, and when your business is

done, return to escort h er to her new home.”

Nicholas agreed that the landlady talked sense, and when he had

promised that he would ride from Iffley every day to make inquiry, which

he would immediately communicate to Dymchurch by stagecoach, the Doctor

felt in a happier frame of mind.]

“Allow me to know a little more about women than you do, you old

anchorite,” he laughed. “And since she seems adverse to my presence, I

promise you I will not worry her. I will only call her news and submit

it on to you.”

“I warrant that after a day or so’s rest,” said Syn, “she will be

asking you to sing her your cheerful songs of Spain. I know so well

that you will cheer her back to speedy health and good spirits.”

“I’ll do my best to that end, believe me,” said Nicholas heartily.

“When you return I will put my best coach and cattle at your command,

to make her journey easier.”

Two days later Doctor Syn knelt by his wife’s bed, and with his arms

around her took a loving farewell. She clung to him like a frightened

child and whispered, “Take care of yourself, dear Christopher, and

promise me that nothing shall make you unhappy.”

“So long as we love each other, nothing could,” he answered.

And so he left her, riding his own horse, and leading another which

Nicholas had lent hi m for this saddle-bags.

In this way he accomplished the journey quicker than had he taken

coach. His welcome to Dymchurch was enthusiastic. He found that the

builders had completed the improvements to the vicarage, and he was

satisfied that Imogene’s every wish had been most tastefully carried

out. Joyfully the Doctor wrote to his wife telling her that here was a

home of which they could be proud, and in which he knew they would find

happiness.

Nicholas was as good as his word, and each day his letters were more

cheerful than the last, describing Imogene’s improvement. The great day

of Induction came, and with great solemnity the Dignitaries of

Canterbury instituted and invested their “Well-beloved in Christ,

Christopher Syn, Doctor of Right, Members and Appurtenances thereunto

belonging.”

It was arranged that he should preach his inauguration sermon upon

the following Sunday, and then post back to Oxford to bring his wife,

whom the whole village were agog to welcome. On the Saturday morning

Tony left his friend sitting in the completed Spanish alcove, for the

sun was warm and bright, and the Doctor wished to contemplate his

address in the open air. He had not been alone, however, above a few

moments when Tony returned with a letter in his hand.

“You will forgive me, Christopher, disturbing your mediations, but

the Mail has just driven by, and I warrant brings you the most

delightful inspiration.”

“From our good Nicholas?” asked Syn, joyfully holding out his hand

for the letter.

– 58 -

“No, better still,” laughed Tony. “It is from Imogene herself. This

shows that she is better. I will leave you to read it in peace, and

will call for you at dinner-time.” For the Doctor was residing at the

Court-House.

“It will be nice to read my first letter in her own Spanish garden,”

said Doctor Syn, smiling happily.

Some two hours later Tony re-entered the Vicarage garden, but this

time with his wife upon his arm. Approaching the alcove, the young man

called out gaily, “Study hours are over, Christopher. Dinner is served.

What news from Imogene?”

Receiving no answer, and thinking that the parson might have retired

to his new library, they entered the alcove and received a shock.

Doctor Syn sat in one of the Spanish seats staring vacantly before him.

He sat rigidly, high tightly griped fits pressed hard upon his knees.

All youth had gone from his face, and his cheeks were a ghastly pallor.

His lips were drawn apart in a hideous grin, showing clenched teeth

biting hard. But what horrified his friends most was to perceive a vivid

white lock that had appeared miraculously in his long raven hair, and,

adding to their terror, they both heard a continual deep moaning that

steadily arose from his throat.

“In heaven’s name wha t ails you, man?” cried Tony when he could find

his voice.

The Doctor’s unseeing eyes did not flicker, but the moaning increased

until it shaped these words, “The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken

away.” Without warning the stricken man’s finer twitche d convulsively,

and a crumpled piece of paper fell upon the Spanish paving-stones.

Slowly he got to his feet with all the action of an old paralyzed man,

and raising his arms to the sky, he shook his clawing fingers at what he

seemed to see there. He the n completed his text with the most damnable

alteration, as he cried in a loud voice, full of venom, “Cursed be the

name of the Lord,”

“Is Imogene dead?” whispered Tony.

“Had it been only that,” he moaned, “you would not have found me here

so stricken. I have received a letter straight from Hell. If you have

courage, read it.”

Standing erect, and as tense as a soldier about to be shot, he

pointed to the letter, without looking at it. Terrified, Tony’s wife

bent down, picked it up and gave it all crumbled to her husband, who

mechanically smoothed it out, and without knowing what he did, read it

aloud in a low, scared voice.

“I cannot ask forgiveness for myself, but just for my mistake. Why

did I not guess that I loved Nicholas? He lives in the s un I worship,

while you, with all your goodness, float in mists—cold mists. With an

aching heart for you and for myself, I must obey the orders of what is

stronger than myself. From you I have gone to follow my destiny. You

will never find us. I implore you not to seek. When you read this we

shall be far way. We are already fleeing from cold England, and from now

the seas will ever roll between us.

– 59 -

All blame is mine, not yours. I do not matter. I have damned myself.

But I cannot be true to the blackness of your cloth. I could not face a