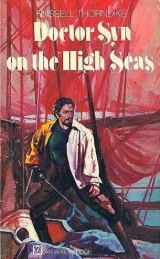

Текст книги "Doctor Syn on the High Seas"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Doctor Syn on the High Seas

by

Russell Thorndike

1936

keyed by Connie Lewis

To the memory of

John Buchan

under whose auscpices Doctor Syn

was first published, I respectfully

dedicate this volume, which

completes the Doctor’s history

Contents

Prologue: The Syns o’Lydd ……………………….. 4

1 Doctor Syn Meets Mister Mips ……………………… 6

2 Doctor Syn Becomes a Squire of Dames ………………. 10

3 Doctor Syn Escapes ………………………………. 17

4 The Challenge …………………………………… 22

5 The Abduction …………………………………… 29

6 The Duel ……………………………………….. 33

7 The Friend of the Family …………………………. 51

8 The Elopement …………………………………… 54

9 The Dead Man ……………………………………. 61

10 The Odyssey Begins ………………………………. 62

11 Pirates ………………………………………… 71

12 Syn Buys a Body and Soul …………………………. 75

13 Redskins ……………………………………….. 83

14 Clegg’s Harpoon …………………………………. 93

15 Syn Hoists the Black Flag ………………………… 102

16 The Red-Bearded Planter ………………………….. 104

17 Clegg’s “Imogene” ……………………………….. 106

18 Mutiny …………………………………………. 107

19 The Mulatto …………………………………….. 109

20 The Return ……………………………………….

– 3 -

Prologue

The Syns o’Lydd

Syn is a name synonymous with “law and order” upon Romney Marsh. The

Syns o’Lydd have been legal prolocutors and attorneys-at-law for

Marshmen since the old days when Thomas Wolsey raised the lofty

campanile of the parish church to heighten the glory of God in the

neighbourhood, and incidentally to typify his own ambition. No doubt a

Syn of those days was as useful to the Ipswich grazier’s son as other

Syns have been to native graziers upon the Marsh. Whenever they fell

into legal difficulties there was always a Syn to pull them out.

So: an ancient town, Lydd; and an ancient race, the Syns.

Prolific, too, as their massed ranks of tombstones in the churchyard

show; while their mural tablets in the church itself serve as a

testimony for all time to the family’s integrity and learnin g.

Go where you will in the neighbourhood, and rummage amongst old

chests and cupboards until you have collected a pile of legal documents,

ancient and modern, as high as Wolsey’s Tower, and you will indeed be

hard put to discover one parchment that does not show the signature of a

Syn attorney. Statutes, recognizances, fines, conveyance of land or

messuage, recoveries, easements, vouchers, testaments and bequests—the

signature of Syn appears upon them all.

Of comfortable means they always seem possessed. They inhabited the

most mellow houses in Lydd and the adjacent New Romney. While waiting

for clients, they purchased for themselves, until by judicious

bargaining they gradually acquired much fertile land, large flocks of

good wool, and such substantial homesteads that no other family could

boast of a more delectable name upon the Marsh.

When there were no more purchasable properties upon the Levels of the

Marsh, they lifted their eyes into the hills, carrying their territorial

conquests along the skyline from Aldington to Lympne. But when they

realized that no financial embarrassment could shift the ancient

Pemburys from their fastness of Lympne Castle, they pushed their own

family possessions inland, acquiring property in Bonnington, Bilsington

and Appledore, until there was even a Syn attorney secure in distant

Tenterden, possessing the best cellars and stables in that comfortable

sleepy town.

Now, the holding of land upon the hills gave to the Syns, as it did

to other Marshmen in like case, a sense of security, for

the reclaimed pasturage of Romney Marsh owed its existence to the

Dymchurch Wall, which held the sea in check. The slogan of

the Marsh, “Serve God, honour the King; but first maintain the Wall”,

showed that possible calamity wa s ever in their minds, and Marshmen like

to think they had a retreat in the uplands in the event of the sea

breaking through and overwhelming the lower Levels. As folk in face of

a common danger are apt to hang together, so did the Marshmen show a

loyalty to one another. But none were so clannish as the Syns. They

inter-married. Syn kith led Syn kin to the altar, and in due course

added further cousins to the Syns. But just as in the most fruitful

tree will sometimes have its barren period in all its

– 4 -

branches, so did the Syn dynasty have its sterile age, and this in the

mid years of the eighteenth century, the time in which this history is

about to be

unfolded. Then were the Syns sadly depleted. Jacobite tendencies

caused the family to send their best blood to be spilled in the Young

Pretender’s cause. Then an epidemic of ague which swept the Marsh took

heavy toll, so that the Syns, who had in the past multiplied so

exceedingly and covered the lands of the Levels of Romney, Welland, and

Denge; the Syns who had covered as many dead sheepskins with ink as they

had covered living sheepskins with wool, found themselves ten years

after the “45” bereft of their good men and true, and represented only

by old Solomon Syn, attorney at Romney, and his nephew Christopher Syn,

the youngest Don at Queen’s College, Oxford, and the youngest Doctor of

Divinity in either of the Great Universities.

His father, Septimus Syn, had been clerk to the Lords of the Level of

Romney Marsh, under the magistracy of Sir Charles Cobtree, who resided

at the Court House of Dymchurch-under-the-Wall. A tall, thin and

austere man, this Septimus, who to all outward appearances was as dry as

the parchments over which he toiled. But beneath his legal dustiness

there must have been burned a bright spark of adventurous romance, for

at the outbreak of the “45” he cast aside his quills and sandbox,

buckled on his sword, and took ship to Scotland, where he joined the

Young Pretender’s force. He wisely left his wife and only child under

the joint guardianship of his elder brother Solomon and Sir Charles

Cobtree. Wisely, for with three of his brothers he was killed at

Culloden. His wife followed him to the grave the same year—of a broken

heart, it was said—and thus at the age of eighteen was Christopher Syn

an orphan. Besides his two excellent guardians, his parents had

bequeathed to him many other valuable assets: a sufficient sum of money

to insure his independence and a brain and personality capable of

improving with security.

In the year 1754, when this history begins, Christopher Syn was in his

twenty-fifth year, and, as resident classical tutor at Queen’s College,

was respected by his elders and popular with

his students. As his great friend Antony Cobtree told his father, Sir

Charles, at Dymchurch, “I owe my degree to Christopher’s patience and

perseverence. By applying the spur at the right moment he lifted me

over the hedges that barred my way to scholarship.”

Although beloved by all, the young Doctor, two years juni or to Tony

Cobtree, was a sombre, tragic figure. Eyes deep, piercing and alive.

Hair raven black. Tall, slim and weird, with a brooding melancholy that

faded only when he smiled, and that because his smile conveyed a

princely graciousness, and a pledge of loyal friendship to the fortunate

recipient. Yes, a man of classic beauty and strength well equipped to

face and overcome whatever fate might hold in store for him. As an

orator he was magnificent, for each spoken syllable claimed its utmost

value, and every phrase its place of full significance, and backed in

all its moods by expressive movements of his wonderful hands, whose

strong delicacy could express more than most men’s tongues. A

personality that could not fail to make its mark in any walk of li fe,

but was at present confined within the bounds of scholarship at Oxford

University, a Doctor of Divinity. A priest. But more than all a man of

high

romance.

– 5 -

Chapter 1

Doctor Syn Meets Mister Mipps

On a misty morning of late Se ptember in the year 1754, young

Christopher Syn, D.D., was riding along the flat top of the Dymchurch

SeaWall in the direction of Lympne.

The Oxford Summer Vacation was drawing to its close, and he had spent

it happily, partly with his uncle, the red-faced, rotund and jovial

attorney at New Romney, and partly with his boon companion Tony Cobtree

at Sir Charles’ old Court-house at Dymchurch.

The young student left the seawall and cantered his horse along the

winding roads that crossed the Marsh. Eventually he reached the grassy

bridle-path which runs along the foot of the hills, and has been made in

years gone by for easy access from camp to camp by the Roman Legions.

On either side the path sloped steeply down into deep, broad dykes, fed

by the surface-water from the hills, but Syn’s tall grey horse picked

his way carefully. Meanwhile the sun, gathering strength, had dispersed

the mist from the hills, and above him he could see his objective—the

grim, frowning walls of Lympne Castle. He was on his way there to

oblige Sir Henry Pembury, who had sent a Castle servant the night before

to the Dymchurch Court-House, bearing a note requesting Doctor Syn to

wait upon the Lord of Lympne at his earliest convenience. Being an old

friend of his Uncle Solomon and a Justice of the Peace, the young cleric

had taken the first opportunity to comply, though neither himself nor

the Cobtrees could think why Sir Henry should thus summon him. Little

did he imagine that such a simple journey was to be the prelude of a

mighty Odyssey which would demand the abandonment of books and

scholarship for murderous adventures with gunpowder and steel.

Opposite the Castle Hill, the bridle-path sloped gently down till

level with the dyke-water, and it was here that a resolute horseman

could save himself a good mile’s detour by leaping the dyke. Knowing

what was required of him, the horse, at the first touch of his master’s

heel, thundered down the slope, and with a sideways jump cleared the

water with a good two foot to spare. Reining him in on the farther

side, Doctor Syn patted the horse’s neck and dismounted, and with the

bridle over his arm led the way up the steep meadow that swept down from

the Castle walls. Throughout the ascent, the man and horse threaded

their way between giant blocks of crumbling masonry—all that was left

of the great Roman Portus Lemanis. In some of these walls could yet be

seen the metal rings for mooring galleys, but the grim

bulwarks which had once held back the sea were now embedded in grass and

used as shelter by the grazing sheep.

Now, bright noon-time, with sun-rays sparkling upon dewy grass-blades

and a fine expanse of sea about one, is no time for a man to reuminate

on ghosts, of things long dead, and yet Doctor Syn fell to wondering

whether any Roman spectre yet mounted his guard in spirit form upon

these walls.

Hardly had this flight of fancy flown to his brain when a sharp voice

belonging to some invisible shape cried out the challenge, “Who goes

there? I knows you. Halt and put yo ur hands above your head.”

Doctor Syn halted, not so much from fear as from astonishment. He

looked hard at the ruined bastion he was approaching, and from which the

voice had issued, but could see nothing unusual.

“Now, then,” went on the voice. “Hands up, I said and I don’t see ‘em

up. No humbug now. I knows you and you knows me.”

“Whom do you take me for?” asked Doctor Syn politely.

– 6 -

“For what you are, of course,” came the indignant answer: “the new

Riding Officer at Sandgate—grey horse and all, and dressed like an

undertaker. Well, you won’t undertake me, because I ain’t a -going to be

undertook.”

It was then that Doctor Syn noticed the brass bell of a blunderbuss

wobbling at him through a fissure in the wall.

“Whom do you take me for?” says you, all innocent like,” went on the

voice sarcastically. ‘“The ruddy Customs,’ says I, ‘who goes spying

round traverns and listening to the talk of poor drunkards in order to

get on my track.”‘ And what for? Why, for having given a hand with a

tub or two to help the Dymchurch lads to a drink or two. We’ve had

about enough of you ruddy Riding Officers, and I for one aint’ standing

much more.”

“And I for another am not standing insult from any man, blunderbuss

or not,” replied Syn sharply. “You call me a Custom man, do you? Well,

as a Marshman born and bred, I take that as an insult—a ruddy insult,

as you seem to like that adjective. You, no doubt, are the Mister Mipps

who works in Wraight’s boatbuilding yard at Dymchurch-under-the-Wall. I

know all about you from my friend Tony Cobtree, the Squire’s son.

You’re a carpenter by trade and a smuggler by profit. I am no smuggler

myself, perhaps for lack of opportunity, by my people, the Syns o’ Lyd,

have saved many a one from the gallows.”

A whistle of astonishment came from the other side of the wall, and

the blunderbluss was withdrawn. “Ah, well, then, there’s no quarrel,

and I’ve been most damnably mistook in you, for which I asks your

honour’s pardon. A Syn o’ Lydd, are you? Then you’ll be old Mister

Solomon’s nephew, no doubt.”

“Quite right. They call me Doctor Syn.”

“What? A sawbones?”

“No, a parson. Come out of that fortification and shake hands.”

“Not me, even though you ain’t the ruddy Customs,” replied the voice.

“No showing myself on no skylines in case ruddy Customs does appear.

Step in, and I’ll give you as good a drink as ever you tasted. But I

ain’t coming out.”

“I approve your caution, Mister Mipps,” laughed the parson. “I’ll

come in, and if the drink you mention has not paid Customs it will of

necessity taste the sweeter.”

So Doctor Syn, after tying his bridle to a ring in the wall, walked

into the ruined bastion.

Mister Mipps gave the young parson the impression that had he not

been bor n a man, he would have been bred a ferret, for the most striking

feature in the little fellow was his nose—long, thin, and inquisitivelooking. As though to balance it, his hair, though scanty, was dragged

back and twisted into a tarred queue which stuck out at the back. In

addition, Mipps proved to be very thin, very small, dressed like a

sailor, and carrying an atmosphere of important impertinence. And,

again like a ferret, he was quick in movement and comically commanding.

“Glad to make your acquai ntance, Mister Mipps,” said the parson,

holding out his hand.

Mipps wiped his on the skirt of his coat and welcomed his guest with

a hard grip. He then removed the bung from a hand anker of brandy, a

neat little cask bound with brass hoops. Doctor Syn drank with relish,

and returned the anker. Mipps in his turn drank deep.

“Good brandy never hurt nobody,” he grinned.

“No, not even a parson,” replied the Doctor with a smile.

“And I drinks to the Syns o’Lydd,” said Mipps, handing the anker back

again.

– 7 -

“And I drink to you,” returned the Doctor, “and to all Marshmen, and

may the Customs never get a one of them to hang upon the grisly tree of

old Jack Ketch.” Then, looking round the interior of the bastion, he

added: “No wonder you preferred to shoot a Riding Officer rather than

being carried away from here. It is all very cozy. I envy you this

gypsy life. It is adventurous; it is simple and natural.”

“Aye, sir,” said Mipps, looking pleased. “A good clod fire always

burning for food and warmth, and that there hurdle with broom on top for

shelter; what more can a man want?”

“Only brandy, it seems, and that you have,” laughed Syn. “How long

have you been in hiding here?”

“Couple of weeks,” replied Mipps. “Though I’m thinki ng of moving

myself on, and legging it down coast for Portsmouth.”

“What do you want to go there for?” asked the parson.

“To ship for the West Indies,” replied the little man. “Thinking of

working my passage on a man o’war as ship’s carpenter. Then I’ll

desert, ‘cos they won’t want for to lose me, being good at my work, and

then I’ll get down amongst the Brethren of the Coast.”

“You mean go pirating?” asked Syn. “For that’s all they are these

days, I understand. The jolly buccaneers have given place to a scum of

bloodyminded pirates. I suppose as a parson I should rebuke you for

such a wish.”

“Never rebuke a man for wishing to live a man’s life and playing the

man when he’s in it,” returned the other. “There’s good and bad in

every trade, and I expects piracy included. And I’ll play the man with

the dirtiest of ‘em. Small I may be, but I’ve grit sharp as flint. A

life of adventure for me. And from all accounts you gets it there.

Battle, murder—”

“Aye, and sudden death,” completed th e Doctor.

“Aye, aye, sir,” grinned Mipps; “but always allowing that you don’t

shoot first and straight.”

“There’s Execution Dock too,” argued the parson. “Have you thought

of that?”

“It’s better to die in old England at the last,” said Mipps.

“Besides, some of us has been born with a rare talent for escape, and

I’d never believe no one could hang me till I felt myself cut down.”

“A true adventurer, I see,” replied Doctor Syn; “and once more I envy

you. Whether you are boasting of your talents or not, I cannot say as

yet, though it seems that they are to be put to an immediate test.

While we have been talking, I have had my eye on Lympne Castle, and it

may interest you to know that three horsemen are riding down along the

western wall. It is significant to me that they are heading in our

direction, and that their leader is riding a dappled grey, very similar

to mine.”

“Sandgate swine,” hissed Mipps, grasping his blunderbuss. “Well,

I’ll at least prove my boast about shooting first and straight.”

‘You’ll attempt no such folly,” retorted Syn sharply. “Unless of

course you wish to forgo all possibility of becoming a good and bloodyminded pirate. You leave the officers to me, and you may yet see your

battle and murder on the Spanish Main. Hold these, and keep yourself

most religiously out of sight.”

Doctor syn had quickly unbuttoned his long black riding-coat, and

from one of his breeches pockets had taken out a handful of coins. Then

he counted into the little man’s hand, saying: “Three guinea spades,

two crowns and a new fourpenny. Keep them safely and yourself hidden,

or you’ll hang.”

– 8 -

Waiting a few moments till the approaching riders were behind a clump

of trees, he slipped out of the bastion walls and untethered his horse.

By the time the officers had emerged from the trees he was slowly

climbing the hill towards them, and since there were many other ruins

scattered about the hillside, there was nothing to connect with the

bastion occupied by Mipps. Meanwhil e, the fugitive, with his weapon at

the ready, cautiously peeped through a hole in the wall, straining his

ears

to listen to whatever the parson might say. This was easy enough, since

the voice of the officer turned out to be coarse, loud and overbearing,

while that of the parson extremely clear -spoken.

The officer was the first to speak. “Have you seen anything, you,

sir, of a dirty-looking little rat of a man in this immediate

neighbourhood?”

“I was about to put the very same question to you, sir,” replied

Doctor Syn; “for he must have passed within a few yards of you as he

went up the hill but now. I hope for your own sakes that you are not

anxious as I am to lay him by the heels.”

“Considering he’s an approved smuggler and we are Riding Offi cers for

Customers,” replied the officer, “I should say that no one could be more

anxious than we are to shackle him. What’s your quarrel with the

rascal?”

‘Just this,” replied Syn, making a wry face as he turned out the

empty lining of his breeches pocket. “He came upon me unawares, and

relieved this very pocket of three guinea-pieces, two crowns, and a

sliver fourpenny.”

“And you offered no resistance?” asked the officer scornfully. “An

agile man like you, tall, young and commanding, should have been a match

for that little rat. Or did you resist him and let him get the better

of you?”

Doctor Syn shook his head. “I did not resist for two reasons.

First, I am a parson and man of peace. And, Secondly, I preferred to

give him my gold rather than let him give me his lead.”

“Aye, and the revered young gentleman’s quite right,” said one of the

other officers. “That there Mipps would pull a blunderbuss at a man as

soon as I would at a rabbit.”

“Which way did he go? Up the hill, you said? An d it’s just time for

the carrier’s cart to start for Ashford. He’ll no doubt use some of

your money to save his legs. Come on, my lads, we’ll ride him down

yet,” And the officer turned his horse.

“I’ll be vastly obliged if you catch him,” called out the parson. “I

am but now on my way to lodge complaint with Sir Henry Pembury, who is a

Justice of the Peace. I am Doctor Syn, residing at the Court-House of

Dymchurch, and I shall be grateful if you can return at least some of

the money to that house. Sir Charles Cobtree is also a magistrate, as

you may know.”

“We’ll catch the bit of gallows meat before he gets much farther,

don’t you worry,” and, followed by his assistants, the officer set his

spurs to his horse and galloped up the hill.

When it w as safe for Doctor Syn to return to the bastion, he found

his comical little companion chuckling. “Well, you certainly settled

them very neat, sir. But I must first give you the lie and retun the

money. Here it is.”

“No indeed,” smiled the parson. “So long as you have it I have told

no lie except that you went up the hill. Instead, I strongly advise you

to go down it. Get on to the friendly Marsh, and use the money to help

you the quicker towards Portsmouth. Were it not for my cloth and duty,

I should be tempted to accompany you. Together we could rule it royally

amongst the pirates. Who knows but that we might not terrorize the

Spanish Main?”

– 9 -

“Well, sir,” replied Mipps with a wink, “if ever you should tire of

your pulpit, go avoyaging and fall into my hands, I pledge you my

solemn word that I will not make you walk the plank. You shall walk the

poop-deck with a sword at your side and a sash stuffed with pistols.

Success to us both. Long life for the King, and Down with the

Government and Customs.”

Doctor Syn laughed, and humorously drank the proffered toast, adding

that should he ever tire of his own profession in England, he would

leave his beloved brethren to another’s cure and seek out the wilder

Brethren of the Coast, where no doubt he and Mister Mipps might

forgather on the poop of some black pirate ship.

Great would have been the astonishment of these ill-assorted

companions had they realized that very soon their joking was to turn

into grim reality. Ignorant of this, however, they parted after mutual

commendations of Good Luck, Mipps shouldering his few bundled

possessions and taking the lower road for Portsmouth by way of Dymchurch

and Rye, and Doctor Syn leading his horse up the steep incline to Lympne

Castle.

At the top of the hill, under shadow of the old bulwarks, he turned

and looked back upon the flat Marshland, intersected with the slivery

ribboned water of the dykes, and spread out beneath him like a vast map.

He was amused to see that his little companion had already reached the

dyke, and from somewhere in the grass Mipps had discovered a long plank,

which he had successfully pushed across the water, and over this

perilous bridge the little man was now walking. And then there came,

owing to his former conversation with Mister Mipps, the first line of a

chanty that was destined to become the terror of the pirate crews. “Oh,

here’s to the feet that have walked the plank.” Aye, Aye, sir, a grim

slogan that was to strike fear into the very fo’c’sles of the worst

ships flying the Jolly Roger. Mister Mipps wobbled over to the other

side of the dyke and then turned round and waved. Doctor Syn waved

back.